Category: Economics

Sex ratios matter

That is a more general way of putting my immigration point from two days ago. Prevailing debates focus on the number of immigrants, or perhaps their legality, but there is a broader point.

Do we want more men or more women? Having women around improves the behavior of the men. On the other hand, if you fear Hispanic culture and its sheer numbers, lots of rootless men may be the best we can do. They won’t have many children. Then you should be a little happier with the status quo than many people are.

If you are a cosmopolitan, you might be willing to accept lower numbers of immigrants in return for more women, or a higher percentage of women. This could mean larger numbers of American-born Latinos in the long run and of course fewer suffering "old maids" (you can attain this status by your early twenties) back in Mexico.

Trading up

How is this for a scheme?:

My name is Kyle MacDonald and I am trying to trade one red paperclip for a house. I started with one red paperclip on July 12th, 2005 and I am making a series of trades for bigger or better things. My current item up for trade is one year in Phoenix. Do you want one year of FREE rent in Phoenix? Pop your offer over to me at ([email protected])… You can see the current offers here. I live in Montreal Canada but will go anywhere in the world for the right offer.

But has he melted down his pennies? Here is the web site, which chronicles the trades so far. No, I cannot prove this is real but the story seems to pan out. Thanks to Robert Saunders for the pointer.

Should you melt down your pennies?

My much-beloved Financial Times gets one wrong:

It could soon be worth Americans melting down their pennies for scrap, if zinc and copper prices continue their current rate of increase.

Copper prices have risen 30 per cent so far this year, and zinc is up 55 per cent – a rise of about $550 a tonne in a little more than three weeks.

A rise by the same magnitude would make the metal content in the US one cent coin worth more than its face value.

The weight of 160 pennies – also known as a one cent coin – comes to a pound, worth a face value of $1.60. But – with each penny made of 97.5 per cent zinc and 2.5 per cent copper – based on current prices, the metal value is worth about $1.36. Therefore another 25 cents-a-pound rise in zinc, or about $551 a tonne, would see the metal value of the US penny worth more than the monetary value.

We all know, of course, that you should not exercise an option before its expiration. The longer time runs, the greater the chance for price to bounce around. Once you are "out of the money," further drops in price don’t hurt you any. But "in the money," you gain from price movements in your favor. So hold onto those pennies and wait. Yes there are complications (what is the stochastic process governing these prices?) but most likely the standard result holds up.

The Tyranny of the Alphabet

In economics there is a norm that authors are listed alphabetically. The norm is surprisingly strong and deviations are punished. On my first paper with Eric Helland we tossed for first authorship, I won, and we noted the names were listed in random order. Believe it or not, Helland’s tenure committee grilled him on this point and as a result we switched to alphabetical ordering on all our subsequent papers. Citation counts, however, are historically assigned only to the first listed author and later listed authors are often buried under the et al. monster.

Do you think these effects are too tiny to matter? Take a look at the Yellow Pages and see how many firms choose A-names, AA-names, and AAA-names. Even more surprisingly, a new paper (free, working version, Winter 06, JEP) demonstrates that these effects have important consequences for careers in economics. Faculty members in top departments with surnames beginning with letters earlier in the alphabet are substantially more likely to be tenured, be fellows of the Econometrics Society, and even win Nobel prizes (let’s see, Arrow, Buchanan Coase…hmmm). No such effects are found in psychology where the alphabetical norm is not followed.

I’m delighted that my young co-author, Amanda Agan, has a great career ahead of her but if Helland wins the Nobel I am going to be very annoyed.

It’s time to end the tyranny of the alphabet! The AER should announce a name randomization policy unless authors otherwise instruct. Barring that, I wish henceforth be known as Alex Abarrok.

Rating the Millennium Challenge Corporation

Lord Kelvin said "If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it." He’s right which is one reason the explosion in measurement in development economics and foreign aid is so important. Reagrding the latter the Millennium Challenge Corporation awards aid to countries that perform well on a set of variables such as political rights, civil liberties, the costs of starting a business, trade policy and other variables. It’s important that most of these variables are measured by outside organizations and not the countries getting the aid.

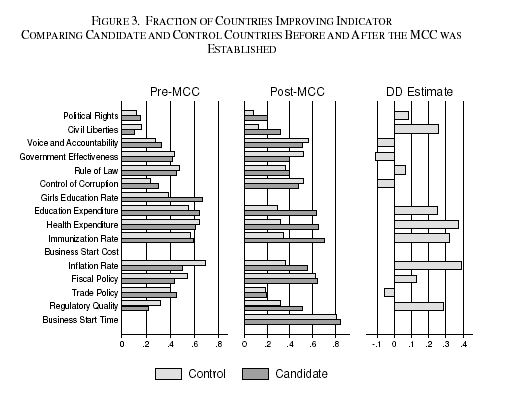

How well has the MCC worked? In a new paper Doug Johnson and Tristan Zajonc find that candidates for MCC aid improve their performance to a greater degree on more indicators than similar control countries. Johnson and Zajonc have a great graph which illustrates one of their research designs. The first panel is candidate and control countries before the MCC when we would not expect many differences, the second panel is the same countries after the MCC was put in place when we would expect the MCC to have an incentive effect on candidate but not control countries, the last panel subtracts the differences in the second panel from the differences in the first to arrive at the difference-in-difference estimate – most of the gains are positive and fairly large.

We do not yet have any evidence that improvement on the indicators will improve growth or reduce poverty but at least we are measuring, the first to step to improving.

Mexico fact of the day

Or is it China fact of the day?

…each doubling of distance reduces trade by 90%. For example, the distance between Los Angeles and Tijuana is about 150 miles. If Tijuana were on the other side of the Pacific instead of across the border in Mexico and if this distance were increased to 10,000 miles, the amount of trade would drop by a factor of 44. Other things held constant, expect the amount of commerce between a Shanghai resident and an LA residence to be only about 2% of the commerce between Tijuana and LA.

That is from Ed Leamer’s review of Tom Friedman, cited by Alex.

John Lott sues Steve Levitt?

Or so the Chicago Tribune reports:

John Lott Jr. of Virginia, a former U. of C. visiting professor, alleges that Levitt defamed him in the book by claiming that other scholars had tried and failed to confirm Lott’s conclusion that allowing people to carry concealed weapons reduces crime.

"!" is all I can say…thanks to www.politicaltheory.info for the pointer.

Should we just build a big fence?

To keep out Mexicans, that is.

For purposes of argument, let us say you are anti-immigration. And let us say the fence would cost nothing to build and maintain. You still might not want one.

Mexicans illegals enter the U.S. through two major channels. They run (or swim) across the border, or they buy illegal papers. Usually the papers cost more than the hiring the crossing guide. The papers make for an easier and safer journey, for obvious reasons. Mexican women, I might add, are more likely to use false papers, given their (their father’s?) greater aversion to the physical strain of four days in the desert.

If you shut off the desert walks (assume the fence is impregnable, ha!), more Mexicans will use illegal papers.

Did I add I would expect the cost of the papers to fall, not rise? Many Mexicans don’t trust the purchase of papers, as opposed to the desert walk. If the walk were impossible, networks for manufacture and sale of the papers would become much better developed. The illegal papers would become much cheaper and much more widely used.

In other words, more young women will come. Many of the Mexican men will have wives here, not back home. Many more young Mexicans will be born on U.S. soil.

Get the picture? Hispanamerica is coming, like it or not. Let’s deal with it constructively.

Opposite day: Tyrone on resource pessimism

Tyler, you are always so optimistic. But your own "dismal science" offers neither empirics nor analysis to back this attitude up.

The standard economic arguments about resources focus on the margin, while the real problem is infra-marginal. Don’t be misled by all that talk of prices and substitution. We are running out of resources and soon.

Think about eating your beloved dark chocolate, Tyler. Let’s say you have only four squares left of Lindt in the cupboard. Yes, as you eat more the shadow price of each remaining square goes up. Big deal. You are still going to eat all the chocolate before dinner. Economics tells us only that you will end up on the Pareto frontier, but that frontier still has some pretty miserable points. We are about to approach them. Who cares if prices mean that we meet our doom while equating private first-order conditions? We are simply too voracious for the resources at our disposal.

Market signals and property rights do not work for the globe as a whole, unless you have monopoly ownership of the entire world (hmm…). Property rights work best for local problems, such as fishing in a single lake or who should wash the dishes. Private property won’t cure the problems of bad air, poisoned oceans, global warming, or the overall carrying capacity of the planet. We will get doom, doom, and more doom.

The real question is empirical: are global demands for resources big enough so that the problem resembles you with your four squares of chocolate? Yes. The environment is toast, sooner or later and probably sooner. And it is doomed precisely because capitalism is such a wonderful productive machine. Do you really think you can fill the planet with so much rapacious human biomass without significant and indeed overpowering external effects? Our only hope is that we all become plugged-in machines who don’t need much of an environment any longer.

It is true that resources prices have been falling, on average, for some time now. But the Industrial Revolution is a remarkably recent development and we are just getting started. Mankind’s current productive powers truly are unprecedented, a fact which you libertarians love to stress in other contexts, just not this one.

It would be mere luck if energy-saving technologies outraced nature-destroying ones. And even if this were the case for a while, energy-saving technologies, in the long run, simply encourage us to raise our rapaciousness up another notch. The infra-marginal becomes even more infra- than we ever dreamed.

Now let us get speculative. Did I mention that in the economics of the future — once we are in exponential growth modes — the concept of price will hardly matter? It will be more like an engineering problems where 10x of today’s gdp is produced every week, and we have to see whether this wrecks the globe in ten or rather twenty years’ time. Don’t even bother recycling. Furthermore all you futuristic nerds out there should downgrade the relevance of price theory, given the size of the changes you have in mind.

My parting shot: Maybe you think I am a pessimist. But it probably is better if resource pessimism is true. Life as a hunter-gatherer is still life. And those Pygmies produced some pretty good vocal music. If the price of energy were to keep falling, that would mean everyone could, within a few generations time, own the destructive power of a nuclear weapon in his or her iPod. Now that’s scary.

As I have said in the past, Tyrone really is a pessimistic fellow. If that dark chocolate is gone, it is usually because I ate it in advance, knowing he would otherwise steal my supply. There are only so many cupboards in the kitchen, and Tyrone has learned all my hiding places. And why didn’t I buy more at the store in the first place? It is simple: I had to take Tyrone to his Zen Buddhism class; this sad sack doesn’t own a car.

Contingent Fees for Julia Roberts (and Erin Brockovich)

Here is more from my debate with Jim Copland on contingent fees.

Movie stars also work on contingent fee (they get paid a share of

the gross). Using your argument this causes them to go for films with a

low probability of a high payoff – the potential blockbuster that alas

is usually a dud. If we regulated fees so that movie stars could be

paid only a straight salary that would certainly change how movies are

financed. The studios (big law firms), for example, would become more

important. A few actors (lawyers) would make less money but the average

actor would make more (if you don’t give people a lottery ticket you

have to increase their average salary). But would changing how actors

are paid really improve the quality of the movies? I doubt it.If you want better movies there’s only one solid method, attack the

source of the problem, and raise the taste level of the public. If the

public demands Armageddon

that is what they will get. The same is true of improving the tort

system – fiddling around with fees won’t do it – we need to address the

substantive issues that give judges and juries a taste for bad law.

A Debate on Contingent Fees

Jim Copland and I debate contingent fees at PointofLaw.com. I was pleased with this statement of my position:

If a lawyer and her client want to contract in Lira what business is

it of the state to interfere? If the lawyer and client agree on an

incentive plan, why should that be regulated? Do we want to regulate

contingent fees in other areas? A money-back guarantee, for example, is

a contingent fee – you pay only if the product is a winner. A tip is a

contingent fee – you pay only if the service was good.True, not all contracts should be respected – we don’t enforce

contracts against the public interest – nevertheless, my spider-sense

starts to tingle whenever reformers of any stripe try to abrogate

private contracting.

Flat Buster

Ed Leamer reviews Thomas Friedman’s The World is Flat.

When the Journal of Economic Literature asked me to write a review of The World is Flat, by Thomas Friedman, I responded with enthusiasm, knowing it wouldn’t take much effort on my part. As soon as I received a copy of the book, I shipped it overnight by UPS to India to have the work done. I was promised a one-day turn-around for a fee of $100. Here is what I received by e-mail the next day: “This book is truly marvelous. It is perhaps the greatest book ever written. It will surely change the course of human

history.” That struck me as possibly accurate but a bit too short and too generic to make the JEL happy, and I decided, with great disappointment, to do the work myself.

Don’t let the opening fool you, in the course of much fun at Friedman’s expense Leamer does a superb job of reviewing economic geography, trade theory, and recent economic history. And lest you think he picks easy targets, Paul Samuelson and others come in for some knocks as well.

Hat tip to Prashant Kothari at the Indian Economic Blog.

French economics

Earlier I wrote that French students need more Bastiat and less Foucault. Supporting evidence is provided by The International Herald Tribune which notes:

In a 22-country survey published in January, France was the only nation

disagreeing with the premise that the best system is "the free-market

economy." In the poll, conducted by the University of Maryland, only 36

percent of French respondents agreed, compared with 65 percent in

Germany, 66 percent in Britain, 71 percent in the United States and 74

percent in China (!, AT)…."The question of how economics is taught in France, both at the bottom

and at the top of the educational pyramid, is at the heart of the

current crisis," said Jean-Pierre Boisivon, director of the Enterprise

Institute…"In France we are still stuck in 1970s Keynesian-style economics – we

live in the world of 30 years ago," he said. …And then there are the textbooks. One, published by Nathan and widely

used by final-year students, has this to say on p. 137: "One must

analyze the salary as purchasing power that you could not cut without

sparking a deflationary spiral and thus higher unemployment." Another

popular textbook, published by La Découverte, asks on p. 164: "Are

there still enough jobs for everyone?" It then suggests that the state

subsidize jobs in the public sector: "We can seriously envisage this

because our economy allows us already to support a large number of

unemployed people."These arguments were frequently used on the streets in recent weeks,

where many protesters said raising salaries and subsidizing work was a

better way to cut joblessness than flexibility.

Hat tip to Peter Gordon who is teaching in Paris but finds his students considerably more sophisticated.

Markets in everything

Take my son to the prom. At $500 cash and $300 expenses, surely he is charming.

Bias at the New York Times

The Times has a biased article on school vouchers. Surprisingly, the bias is in favor of vouchers. Oh sure, there’s the usual crazed principal sounding like a cross between Che Guevera and Andrea Dworkin as she attacks vouchers for "raping the public schools of students and resources." Also, I would have liked a better review of the evidence which is strongly in favor of vouchers. Nevertheless, the overwhelming impression of private schools left by the article is delightfully positive.

It’s the stories of little boys and girls sadly left behind by the public schools but now attending private schools like the one "near a verdant hill of churches" that tell the tale. And how about this to bring a tear to your eye?

Breanna Walton, 8, rises before dawn for the long bus ride from

Northeast Washington, "amongst the crime and drugs and all that," in

the words of her mother, April Cole Walton, to Rock Creek

International, near Georgetown University. There, she learns Spanish

with the children of lawyers and diplomats.

The best is left to last:

"I’ll probably go to Washington Latin," said Jhontelle Johnson,

setting her sights on a new charter school opening in August. If not,

she said, "I’d probably be home-schooled."A teacher’s aide, Sheonna Griffin, looked askance. "You don’t like public schools?" she asked the child.

Jhontelle turned back, her young eyes flashing. "You can’t make me go," she said.

Sadly, in most of the country they can.