Category: Economics

Pay Go, No Go

It’s not just GM, United Airlines and the Federal government who have made unsustainable promises to current and future retirees. State and local governments have also been irresponsible, to the tune of perhaps a trillion dollars in unfunded liabilities.

For years, governments have been promising generous medical

benefits to millions of schoolteachers, firefighters and other

employees when they retire, yet experts say that virtually none of

these governments have kept track of the mounting price tag. The usual

practice is to budget for health care a year at a time, and to leave

the rest for the future.Off the government balance sheets – out

of sight and out of mind – those obligations have been ballooning as

health care costs have spiraled and as the baby-boom generation has

approached retirement.…most states and cities have set aside no money to pay for retiree

medical benefits. Instead, they use the pay-as-you-go system – paying

for former employees out of current revenue.

Tabarrok on Feldstein on Capital Taxation

The plethora of discount

rates and taxes obscures the basic point in Feldstein’s argument against

capital taxation. Here is a bare-bones version.

There are three

goods, labor, apples and oranges. Assume that the government taxes

oranges at a higher rate than apples. A tax on oranges is also a tax

on labor since you need labor to buy oranges and if the price of

oranges is high the value of your labor is low.

Now let’s show

that a reduction in the orange tax matched by an increase in the labor

tax to keep total tax revenues constant can make everyone better

off. The simplest case is to assume a tax on oranges so high

that no one buys any oranges. Orange tax revenue is therefore zero.

Now we get rid of the tax on oranges and add an equal-revenue tax on labor

(zero). So long as the consumer cares at all about oranges he now buys

more oranges and is better off (because he now consumes a variety of

fruit and has an increased incentive to work). The consumer will still be better off even if we replace the zero-revenue orange tax with a

small labor tax which increases government revenues. The zero-revenue assumption makes the argument obvious but is not at all necessary for the results.

The basic point is that the tax on oranges distorts the labor-leisure choice and the apples-oranges choice. A tax on labor distorts only the labor-leisure choice and so is preferred.

For Feldstein’s argument rename oranges as savings, apples as present consumption and labor as income. To see a counter-argument introduce more people into the model and rename oranges as yachts.

Newspapers as non-profits?

A newspaper company, like a public broadcaster,

could be organized as a not-for-profit, tax-exempt corporation. It

could still sell papers and advertising, it could still develop new

Internet revenues, it would still pay market wages and salaries (or

maybe better), it could re-invest in improving its own staff and

facilities and operations, it just couldn’t make a profit. And it

wouldn’t pay taxes or dividends.

Here is more. As newspaper ads move to the web, draining a key source of revenue, I see a few options:

1. Subscription finance with high prices and few ads. A bit like the Financial Times. Of course this means fewer newspapers and fewer newspaper pages. On the plus side, fewer articles would continue on other, distant pages.

2. Sleazy tabloids. But the competition with the Internet remains.

3. Some clever newspaper coup to take over Web processing of commercial information and leapfrog over ebay and Craigslist.

4. Web products evolve into customized, print-on-demand newspapers. A some major newspapers survive by going the hybrid route, or by merging with their web competitors. "What is a newspaper?" becomes a question of degree and we needn’t mourn the lack of pure newspapers.

5. Non-profits would take in revenue and also raise donations by selling access to social and political networks. What would a date with Maureen Dowd go for?

6. Extremely partisan, low-cost "rag" newspapers, akin to 19th century U.S. experience, and paid for by subscription. Advertisers seek to offend nobody, and thus exert a centrist influence over newspaper content.

I place virtually no weight on option #3. Comments are open.

Markets in charity

‘This is our

months bill and is owing $126.37. It has been a tough month and we are a bit low

on cash’.

That is from Wellington, New Zealand, on TradeMe, the Kiwi equivalent of ebay. Bid here to help out. Thanks to Jason Reid for the pointer.

Martin Feldstein on capital taxation

Follow these numbers, and the bold face is mine:

An example will illustrate the harmful effect of high

taxes on the income from savings and show how the tax reform could make

taxpayers unambiguously better off. Think about someone — call him Joe

— who earns an additional $1,000. If Joe’s marginal tax rate is 35%,

he gets to keep $650. Joe saves $100 of this for his retirement and

spends the rest. If Joe invests these savings in corporate bonds, he

receives a return of 6% before tax and 3.9% after tax. With inflation

of 2%, the 3.9% after-tax return is reduced to a real after-tax return

of only 1.9%. If Joe is now 40 years old, this 1.9% real rate of return

implies that the $100 of savings will be worth $193 in today’s prices

when Joe is 75. So Joe’s reward for the extra work is $550 of extra

consumption now and $193 of extra consumption at age 75.But if the tax rate on the income from saving is

reduced to 15% as the tax panel recommends, the 6% interest rate would

yield 5.1% after tax and 3.1% after both tax and inflation. And with a

3.1% real return, Joe’s $100 of extra saving would grow to $291 in

today’s prices instead of just $193.There are two lessons in this example, each of which

identifies a tax distortion that wastes potential output and therefore

unnecessarily lowers levels of real well-being. The first is that a tax

on interest income is effectively also a tax on the reward for extra

work, cutting the additional consumption at age 75 from $291 to just

$193. Because the high tax rate on interest income reduces the reward

for work (as well as the reward for saving), Joe makes choices that

lower his pretax earnings — fewer hours of work, less work effort,

less investment in skills, etc.The second lesson that follows from the example is

that the tax on interest income substantially distorts the level of

future consumption even if Joe does not make any change in the amount

that he saves. With the same $100 of additional saving, the higher tax

rate reduces his additional retirement consumption from $291 to $193, a

one-third reduction. If Joe responds to the lower real rate of return

that results from the higher tax rate on interest by saving less, the

distortion of consumption is even greater. For example, if Joe would

save $150 out of the extra $1,000 of earnings when his real net return

is 3.1% (instead of saving $100 when the real net return is 1.9%), his

extra consumption at age 75 would be $436, more than twice as much as

with the 35% tax rate. But the key point is that Joe’s future

consumption would be substantially reduced by the higher tax rate even

if he does not change his savings.Taken together, these two lessons imply that a lower

tax rate on interest income, combined with a small increase in the tax

on other earnings, could make Joe unambiguously better off while also

increasing government revenue. More specifically, if reducing the tax

on interest income from 35% to 15% had no effect on Joe’s earnings or

on his initial consumption spending, the government could collect the

same present value of tax revenue from Joe by raising the tax on his

$1,000 of extra earnings from $350 to $385. Although this would cut

Joe’s saving from $100 to $65 (if he keeps his initial consumption

spending unchanged), the higher net return on that saving would give

Joe the same consumption at age 75. In this way, Joe would be neither

better off nor worse off.

But experience shows that Joe would alter his behavior

in response to the lower tax rate. He would earn more at age 40 and

would save more for retirement. This change of behavior makes Joe

better off (or he wouldn’t do it) and the extra earnings and interest

income would raise government revenue above what it would be with a 35%

tax rate. So Joe would be unambiguously better off with the lower tax

rate on interest income and the government would collect more tax

revenue.

Here is the link. Elsewhere from The Wall Street Journal, here is a piece on bargaining theory, thanks to Chris Masse for the pointer.

Markets in everything — cell phones for dogs

As of next March, pet owners will be able to drop the photocopier and staple gun and pick up the phone instead. That’s when PetCell, the first cell phone for dogs, is due to hit pet-store shelves.

Hung off Fido’s collar, the PetCell is a bone-shaped cell phone that will let dog owners talk to their best friend over a two-way speaker.

Developed by PetsMobility, the PetCell works with standard cellular networks and has its own number. It automatically answers when the owner punches in a code on their telephone keypad that means, "Lassie, come home!"

The PetCell will ship in early 2006 and will sell for $350 to $400, the company said.

Here is the story, and thanks to Christopher Meisenzahl for the pointer. While we are on the topic, here is evidence that dogs laugh.

Steve Levitt responds to critics

Read it here. Parting excerpt:

No doubt there will be future research that attempts to overturn our

evidence on legalized abortion. Perhaps they will even succeed. But

this one does not.

I’ve yet to go through the arguments of the critics, much less the response. In the interests of data centralization, leave your comments on the Freakonomics blog.

How to save for your retirement

…for most of us, it would probably be easy to save for retirement if we

were willing to live like your parents did–or at least like my parents

did. One television, no stereo, no VCR, no cable, one (used) car, six

rooms for four people, no eating out, no cell phones, no vacations

other than visiting relatives, stretching meat out with egg and bread

and noodle rings, jello as a salad, turn the light off when you leave

the room and get off the phone–it’s long distance!

Jane Galt has more. Saving is less fun than it used to be, most of all in the United States. That is one reason why we save less, or save only in fun forms, such as capital gains on our homes. The better your society at marketing and retail, the harder it is for abstinence to compete.

How much does Wal-Mart receive in government subsidies?

Uh, not that much. Matt Yglesias should receive a uh…Matt Yglesias award for the post.

Wired Ads a Leading Indicator?

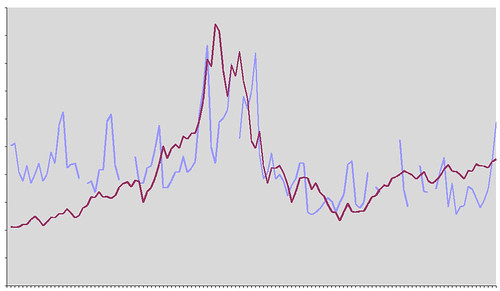

Is it time to invest in technology stocks again? Mark Frauenfelder at Boing Boing Blog points us to this graph (before getting too excited, however, I would want to detrend for seasonality, i.e. the Christmas effect):

Rich Giles made a graph that compares the page counts of past issues of Wired

with the the rise and fall of Nasdaq over the years.You’ll note that the Nasdaq (red) lags Wired’s page count (blue) by a

few months [No longer true, in the updated graph -see below – although they do seem to move together, AT]. I’m not suggesting you go an buy technology shares, but gee, I’m

thinking the reports of money pumping back into technology companies might just

be true given the big up-tick in this months page count (294).

Addendum: There were some problems with the author’s original graph. He corrected and I have reposted. The data are available here. Thanks to the Stalwart and Paul N for pointing me to the problem.

Wisdom about upward-sloping demand curves

MR has had especially good comments lately:

The problem with this thought experiment is that even if every

individual (or all but one) have an upward-sloping individual demand

curve, the market demand curve will still be downward-sloping. The

reason is, when people who seek higher prices will run out of money

faster, thus buying fewer units. So higher prices still lead to fewer

units sold — i.e., a downward-sloping market demand curve.

Or how about this:

Your curve slopes upward until it reaches the point where quantity

times price equals your wealth. From there on, it slopes down (you buy

as much as you can afford, which is less and less at higher prices).So everyone would quickly spend all their money.

Oddly, some goods might end up with demand curves that slope down in

the relevant price range– in spite of the buyers’ preferences!

Perhaps you’ve already spoken your mind, but comments are open again, in case you would like to take another crack at the problem. And remember, spent funds are recycled to sellers and do not represent the destruction of real resources.

10:30 p.m.

Tim Harford and I will be on C-Span, also with Sebastian Mallaby and Bob Hahn. And here is Tim, channeling Thomas Schelling, on why you should burn your Christmas card lists.

Nick Szabo’s blog

One of my main interests is the history of institutions, and in

particular the patterns that recur in successful institutions. These

organizational structures and security mechanisms allow naturally

suspicious strangers to interact with integrity.These patterns include tamper evidence, shared time, unforgeable costliness, separation of duties, the principle of least authority, risk sharing, and learning from our ancestors,

among many others. These patterns have been useful for centuries, and

(I can report after having spent many years working in the computer

network security field) continue to be useful in the Internet era.

Here is the blog. Here are Nick’s essays. The pointer comes from Brad DeLong. Here is Nick on The Playdough Protocols.

How fast is the economy growing?

Arnold Kling, teaming up with Robert Fogel, has the answer.

Does capital taxation hurt an economy?

Following my Econoblog debate with Max Sawicky, Kevin Drum writes:

Basically, I’m on Max’s side: I think taxation of capital should be at roughly the same level as taxation of labor income. However, I believe this mostly for reasons of social justice, and it would certainly be handy to have some rigorous economic evidence to back up my noneconomic instincts on this matter. Something juicy and simple for winning lunchtime debates with conservative friends would be best. Unfortunately, Max punts, saying only, "As you know, empirical research seldom settles arguments."

Let me repeat the chosen comparison: capital taxes vs. gasoline taxes and no subsidies for housing. That is a no-brainer. But still you might be interested in the question of capital taxes vs. labor taxes. Here are some points:

1. Supply-siders writing on capital taxation often make exaggerated claims. Even if you like their conclusions, beware.

2. Taxing dividends, corporate income, returns to savings, and capital gains all involve separate albeit related issues. I am willing to consider zero for the lot. Of that list, the corporate income tax is probably the biggest mess. The capital gains tax is the least harmful. The tax on dividends is the least well understood (in perfect markets theory, the level of dividends should not matter at all). By the way, if you are worried about noise traders, a transactions tax is a better way to address this problem than a capital gains tax.

3. The U.S. currently lacks exorbitantly high levels of capital taxation. Joel Slemrod estimates a rate of about fourteen percent, albeit with many complications and qualifications. N.B.: We lower the rate of tax on capital by engaging in crazy-quilt and distortionary adjustments. Nonetheless it is incorrect to argue "we have high rates of capital taxation and are doing fine, better than Europe." Do not confuse real and nominal tax rates.

Take the capital gains tax. Once you consider bequests and options on loss offsets, the effective rate of tax is arguably no more than five percent. But it is still set up in a screwy way. Bruce Bartlett points me to this short piece on real tax burdens on capital.

4. Peter Lindert has good arguments that favorable capital taxation has helped European economies finance their welfare states.

5. Larry Summers did the best empirical work on how abolishing capital income taxation would boost living standards.

6. Encouraging savings will have a big payoff. If you tax capital at zero, in the long run you will have much more of it. This holds in most plausible views of the world. Max’s examples aside, the supply curve for savings does not generally slope downwards; nor need you write me about various strange counterexamples from Ramsey models. Sooner or later, more capital will kick in to mean a much higher standard of living.

7. Bruce Bartlett points me to this excellent CBO study. It shows how much capital is taxed unevenly; one virtue of a zero rate is to eliminate many of those distortions in a simple way.

8. Remember those arguments about how more money doesn’t make you happier? And we are all in a rat race where we work too hard to win a negative-sum relative status game? I’ve never bought into them, but it’s funny how they suddenly stop coming from the left once the topic is capital vs. labor taxation.

9. The same excellent Slemrod paper (and he is no right-wing supply-side exaggerator) also suggests that the revenue lost from a zero rate on capital would be small. N.B.: The references to this paper are the place to start your reading on this whole topic.

10. Kevin Drum’s belief in social justice should not necessarily lead him to look for arguments for taxing capital. Even if we accept his normative views, there is the all-important question of incidence. Taxing capital can hurt labor. If you are truly keen to tax capital, this is a sign of a high time preference rate, not concern for the poor.

11. Some forms of human capital also should receive favorable tax treatment. Vouchers for primary education and state universities are two examples. I am also happy — in part for equity reasons — to subsidize human capital acquisition through an Earned Income Tax Credit.

12. What is really the difference between capital and labor? Is it simply measured elasticities? The size of each potential tax base? The greater "future orientation" of capital and the possibility for compound returns? All of the above? How much does your answer depend on whether you view capital as a "fund" or as a "collection of capital goods"?

The bottom line: It all depends on the margin. If your levels of government spending allow you to keep labor rates of taxation below 40 percent, I don’t see comparable gains from lowering tax rates on labor. If you have equity concerns, express them through other policy instruments. But if your marginal tax on labor is 65 percent and your tax rate on capital is 15 percent, cut the tax on labor first.

I know it hurts, but all of you non-right-wingers out there should consider a zero rate of taxation on capital. Comments are open.