Category: Economics

Does it cost more to take care of the young or the old?

…some economists are sanguine about the country’s ability to support

the elderly and at the same time provide for the young. Gary Burtless,

a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, noted that the decline in

fertility rates since the 1960’s means that the burden of caring for

the young has decreased dramatically – freeing resources to channel to

the old.The overall burden on the employed will grow, but not

to unprecedented levels. The ratio of people of working age to those

either under 20 or over 65 will decrease to 1.2 in 2050 from about 1.5

today. But this is still an easier load than in 1965, when the country

was awash with children, and the ratio of the working-age population to

each dependent was only 1.1.True, the young are cheaper to

maintain than the old. In 1990, economists at Harvard and M.I.T.,

including David M. Cutler and Lawrence H. Summers of Harvard, estimated

that people over 64 consume 76 percent more than children.Still,

Mr. Burtless estimated that in 2050 a worker will have to sacrifice

49.6 percent of his or her wages – through taxes or other means – to

maintain society’s dependents. That is nearly 6 percentage points more

than in 2000, but it is merely 0.8 percentage points more than 1965.

And the percentage could well be smaller if people work later in life

to pay for more of their keep.The notion of incredible

competition between what the public spends on the aged and what it

spends on the young is driven by fear, Mr. Burtless said. "But so far

the fears have not been grounded," he said. "In fact, we seem to be

able to do both kinds of things. Increase spending on aged and protect

spending on the young."

This is the most hopeful notion I have heard in some time. Here is the story. Here is the home page of Gary Burtless.

Let us not forget about the utility dimension in addition to the fiscal. Is it more fun to care for the very young or the very old? The evidence is not so clear cut. Many people do not enjoy their children as much as they claim; read more here.

Rich Man, Poor Man; Rich State, Poor State

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science is one of my favorite new blogs. It is primarily written by Andrew Gelman, a professor in the Departments of Statistics and Political Science at Columbia University.

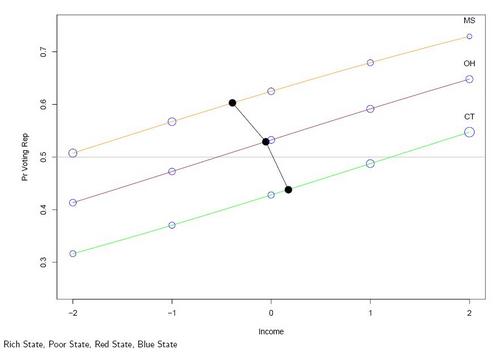

A recent post looks at the difference between red and blue states and red and blue individuals. We all know that in the recent election poorer states tended to vote Republican while richer states tended to vote Democrat. On the basis of the famous maps many people jumped to the conclusion that poorer individuals were voting Republican (Nascar Republicans) while richer individuals were voting Democrat (trust fund Democrats). But the inference is a fallacy, the ecological fallacy. In fact, high-income individuals, as opposed to high-income states, vote Republican with greater likelihood than low-income individuals (the effect is not huge and it may be declining but it is significant).

It’s even true that rich counties tend to vote Republican with greater likelihood than poorer counties. Gelman links to this graph which nicely illustrates the ecological fallacy. The three lines show that within each state higher-income counties are more likely to vote Republican but when you look between states the correlation between income and voting Republican is negative. (Click to enlarge).

The Ricardo effect

The United Arab Emirates says it will use robots as jockeys for camel races from next season.

The move comes after widespread international criticism of the use of young children to ride camels during the long and often hazardous races.

Aid workers say there are up to 40,000 child jockeys working across the Gulf. Many are said to be have been kidnapped and trafficked from South Asia.

The issue of child camel jockeys has been an embarrassing one for the Emirates, says the BBC’s Gulf correspondent Julia Wheeler.

Read more here, and thanks to Dylan Alexander for the pointer.

Addendum: Geekpress offers a photo. And here is yet another photo, with an excellent quotation, courtesy of a new and excellent blog on the Arab Emirates.

DeLong on Hazlitt

Brad DeLong criticizes Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson. First, "because at least half its pages hint that the works of John Maynard

Keynes are an abomination without ever grappling with the Keynesian

argument."

Hazlitt did not say much about Keynes in his famous introduction to economics but he certainly grappled with the Keynesian argument in his lesser-known

The Failure of the ‘New Economics’: An Analysis of the Keynesian Fallacies.

Second, DeLong quotes Hazlitt:

There are men regarded today as brilliant economists, who deprecate

saving and recommend squandering on a national scale as the way of

economic salvation; and when anyone points to what the consequences of

these policies will be in the long run, they reply flippantly, as might

the prodigal son of a warning father: "In the long run we are all

dead." And such shallow wisecracks pass as devastating epigrams and the

ripest wisdom.

According to Brad this quote is "dishonest" and a "misrepresentation," but Keynes did deprecate saving and recommend squandering. Famously:

To dig holes in the ground,” paid for out of savings, will increase,

not only employment, but the real national dividend of useful goods and

services. (General Theory, Ch. 16).

Brad seems to think that Hazlitt quoted Keynes out of context because "What Keynes actually wrote in his Tract on Monetary Reform" was:

Now ‘in the long run’ this [way of summarizing the

quantity theory of money] is probably true…. But this long run is a

misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead.

Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in

tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long

past the ocean is flat again.

But the misreading is Brad’s not Hazlitt’s. Keynes is criticizing classical economics for focusing on the long run and this certainly includes the classical focus on savings as a key to economic growth. Hazlitt, as Brad notes, is restating classical economics so when Hazlitt points out the long-run problems with using spending to increase short-run aggregate demand, Keynes does, in effect, reply "We are all dead in the long run."

For some, it seems, one lesson is not enough. 🙂

Do we have too many *ideas* to choose from?

Mark Steckbeck (his blog is very good) writes:

Barry Schwartz believes that Americans suffer from too many choices. (PDF file) The result is that we become overwhelmed with too many choices, become depressed, and consequently lead less fulfilling.

I’m certain that Schwartz did not mean that there are too many ideas from which to choose to believe in, but why not? It’s overwhelming listening to political ads during campaigns or editorials and stories on major topics in newspapers. As Ronald Coase said, the reasons for regulating markets for goods is no different than the reasons for regulating markets for ideas, execpt that there’s probably more reason to regulate the latter.

I wonder which ideas Schwartz recommends we eliminate from the set from which we choose.

Markets in *everything*

Cataracts cloud her eyes and arthritis stiffens her spine, but Maria Luisa Torres, 70, still walks the streets of the Merced selling her body, as do many elderly women in the downtown heighborhood…Among the thousands of prostitutes in North America’s largest city are hundreds of women in their sixties, seventies and eighties who continue to sell themselves to earn cash to buy food or medicine…

Some of the prostitutes are eighty-five years old.

Men know she is not young, but she chooses to think that "an antique can be more valuable than something new," she explained. She strolled through Jardin Loreto, a nearby park, saying to passing men: "Amor, vamos?" or "My love, shall we go?" After agreeing on a price — often $5 or less — she leads her customer to one of the many run-down hotel rooms nearby. She has been doing this for decades, since she left the coconut fields in Western Mexico. At first she had higher hopes and opened a little sandwich kiosk. But "not even a fly would stop" at her stand, and she turned to the only sure money she could find.

Here is the full story.

What do we know about tipping?

1. Two studies show little relationship between quality of waiter service and size of tip.

2. Hotel bellboys can double the size of their tips, on average, by showing guests how the TV and air conditioning work.

3. Tipping is less prevalent in countries where unease about inequality is especially strong.

4. The more a culture values status and prestige, the more likely that culture will use tipping to reward service.

5. Tips are higher in sunny weather.

6. Servers can increase their tips by giving their names to customers, squatting next to tables, touching their customers, and giving their customers after-dinner mints. (query: how do lap dances fit into this equation?)

7. Drawing a smiley face on the check increases a waitress’s tips by 18 percent but decreases a waiter’s tips by 9 percent.

8. In one study, waitresses increased their tips by 17 percent by wearing flowers in their hair. In general it pays to look distinctive albeit not freaky.

Here is the link. Some of the information draws on studies by Michael Lynn of Cornell. Here is his home page. Here is his page on tipping. Here is his advice on how to increase your tips; he asks that you tip him for it. Here are his dogs.

My questions: Is tipping any harder to explain than why we don’t just leave the restaurant without paying? Given that (almost) everybody tips, is the final incidence more or less neutral for the customers? Do we tip, in part, to produce the illusion of control over how we are treated?

How does “spontaneous order” differ from the “invisible hand theorem”?

One of my Ph.d. students asked me that question. Similarly, you might wonder whether Hayek adds to the Arrow-Hahn-Debreu equilibrium framework. Joe Stiglitz insists no; my answer ran as follows:

The invisible hand theorem assumes some (possibly weakened) version of perfect markets. It suffices for everyone to simply maximize utility or profit, and then all supply and demand curves will cross. Under spontaneous order, cross-market externalities are more significant. Markets are imperfect, so people look to institutions — and other markets — to orient their behavior and to predict the unknowable future. Market choice is a game of interpreting symbols, drawing inferences, and mapping an understanding of context to the appropriate situations. The resulting order is greater and more complex than the partial equilibrium story we might tell about any single market.

As for Adam Smith, he was closer to Hayek…But the dilemma of the Austrian School is whether it can tell this story without economic analysis collapsing into pure context-dependence. How much do we really know about how people interpret economic signals? So far experimental economics — as exemplified by Vernon Smith — has done the most to bridge these gaps.

Another question I heard this week: "Why is it that older people start going deaf, yet still object more to loud music?" I couldn’t really answer that one either.

Security Bonds

A member of the Canadian parliament apparently required that constituents who wanted his help in obtaining visitor visas first post a bond promising that the visitor would return to the home country. (It’s unclear whether any actual exchanges of money took place or whether this was a publicity stunt designed to promote a bill implementing a more formal procedure.)

The ethics of an MP offering money for services is questionable but the basic idea is sound. Australia, for example, has had a Security Bond system for nearly five years. Family who wish to sponsor visitors may be asked to post a bond which is subject to forfeiture if the visitor fails to keep to the terms of the visa. The bond system is good for the government which has fewer illegal visitors to track down (note that I am not here taking a position on the merits or demerits of immigration) but it’s also good for prospective visitors.

Under the old system if the government thought that a visitor might violate the terms of the visa they didn’t let him in. Now the family can post a bond and the visitor is allowed entry – moreover, since the money is returned when the visitor leaves, the system has low costs for honest entrants and their families. Since implementing the system most visitors (68%) are required to post bonds and the entry rate has increased. A good deal all around.

When does fiscal policy work?

Brad DeLong notes:

When can deficit spending in a recession help?

- When it is part of a stable and sustainable structure of economic policy, so that nobody fears that it is the beginning of a process of rampant inflation or expropriation. In that case deficit spending will have no deleterious effects on investment, and to the extent that it gets more money into the hands of those who are temporarily short of cash it will boost demand and employment.

- When things are already so bad (as in 1933 and 1934) that there is no investment anyway: if business confidence is already at its nadir, deficit spending cannot do any harm by reducing investment, and does good by putting people to work and boosting their incomes and their demand.

I’ll add further conditions, none of them absolute. First, it should be accompanied by an expansionary yet stabilizing monetary policy (similar to Brad’s first condition). Second, the money should be well spent, ideally on durable infrastructure. Third, fiscal policy should be a signal of a government’s competence or seriousness about fighting the recession. Fourth, I doubt it does much good if the core problem is bankrupt or otherwise malfunctioning financial institutions.

Mostly I am a skeptic about fiscal policy, if only because discretionary fiscal changes tend to be small relative to modern wealthy economies.

Experimental economics, African style

This settlement in western Kenya, where Ms. Odera lives, has become

a giant test tube, and Ms. Okoth’s instruction is one part of that

experiment. Eventually there will be 10 such test villages, scattered

across the world’s poorest continent.Led by Jeffrey Sachs,

director of the Earth Institute of Columbia University, the project

aims to fight poverty in all its aspects – from health and education to

agriculture and energy in one focused area – to prove that conditions

for millions of people like Ms. Odera and her neighbors can be improved

in just five years.It is an important and uncertain gambit. If

it fails, initiatives like that pushed recently by Prime Minister Tony

Blair of Britain to greatly increase foreign aid to Africa may seem

foolhardy. If a single village cannot be turned around with focused

attention, how can whole communities and even countries be revitalized?…The researchers behind the program are keeping track of every penny

they spend, trying to demonstrate that for a modest amount, somewhere

around $110 per person, a village can be tugged out of poverty.They

have tried to measure exactly how bad Sauri was at the start of the

project last fall. Every home was surveyed to get an accurate portrait

of the population. Blood tests were taken among a smaller group for a

nutritional analysis, because many villagers eat only once a day, and

show it.Blood will also be tested to determine how widespread

the malaria parasite is, and then again later, to see whether the

mosquito bed nets given to every villager help keep more people,

especially children, alive.

Here is the New York Times story. Here is my earlier post on Sachs’s plan. Here is an on-line World Bank discussion about when foreign aid works and doesn’t; they invite MR readers to join in.

My social security debate with Jim Glassman

The most loyal of MR readers will find this old hat, but the debate at this link, originally done for Reason magazine, provides a good summary of my views. Here is my bottom line:

To the benefit caps that we really agree on, Glassman wants to add government-regulated personal accounts. The economics here are straightforward, once unbundled from benefit caps. Our government would raise taxes (or borrow) to finance further private investment in equity markets. Furthermore those investments are to be regulated by the government. I expect that Reason readers, once they hear the plan described in these terms, will be suspicious.

How does sleep compare with death?

Say that you, like me, expect to live another forty years.

Now imagine that I could learn to live with one less hour sleep each night. The extra time adds up to almost two more years of life. And by definition, two more years of awake life. Which is worth about three years of life with one-third sleep.

I would give a great deal to live three more years, but I don’t try so hard to sleep less.

Nor do I enjoy sleep. I enjoy "the feeling of having slept." The best sleep is the sleep I don’t notice at all, and I would do without sleep if I could. It appears that I find death much worse than sleep.

Might I have negative time preference for time (a non-storable) itself? I would rather have an extra year in the distant future than many extra hours — adding up to a year — in the interim.

Much of my negative time preference for time stems from plain curiosity. If I were single at the time, I would give up my last year of life for a year in 2250, if only to see how things turn out (I also would have a chance of trying some neat new goods, but for me that is a lesser attraction).

I would rather be born later than earlier. Even if I did not expect economic growth, I could learn more history. So how much life would I give up for a true and comprehensive account of the future of the human race? How much money?

Say that "deep-freeze" worked and the future were secure. How many people would deposit a penny in the bank and wake up much later as billionaires? Would you have an extra child — one more than you want — in order to freeze her and pre-arrange future care in this manner? Is there a free-rider problem, and if so what must we do to keep people going in the present, thereby maintaining real rates of return for future "sleep astronauts"?

Addendum: Here is Shakespeare’s take, thanks to Robert Schwartz for the pointer.

Rate your date

…you can pop over to TrueDater.com and find out whether your prospective date is anything close to what the profile suggests.

TrueDater, not to be confused with True.com, is a database of reviews written by people who met through online personals. It’s like Amazon.com, only instead of books, you’re reviewing people. More specifically, you are reviewing their ability to represent themselves online.

Here is the story; the prescient Michelle Boardman suggested this idea some time ago.

Addendum: Here is a sample review.

Should we value human life at replacement cost?

Earlier this week I asked whether we should value human life at replacement cost. Michael Vassar wrote me in response:

We should value human life at replacement cost, and we actually value generic human life less than that (negatively?), as demonstrated by the existance of late term abortion (there are almost certainly potential adoptees who would pay many women enough to motivate them to go through labor once late in a pregnancy in exchange for the child, especially considering the actual expenses many incur to adopt), but we should value a particular human life at the lower of total preference for the continuation of that life and replacement cost for that life. For the latter, today replacement cost is infinite, though it needn’t be forever. For the former, the preference varies dramatically depending on situation, but is frequently very high. For simplicity’s sake, and because economical thinking is confusing or corrupting to people below a very high IQ threshold, we maintain a convenient fiction of infinite value. Although we violate this fiction continuously, we do so in an extremely inconsistent manner because the cost of strict obedience or careful public analysis are greater than the costs of irrationality on particular instances. The "ethical questions" raised by science are rather consistently actually situations where new scientific data challenges the viability of convenient fictions, but in the end it always turns out to be possible to ignore the new data and maintain these fictions, or to integrate the new data into life rather seamlessly without disruption. However, the frequency with which these questions occur is increasing.