Category: Economics

Vaccines: The Long Run

Yesterday I discussed some of the reasons for the current shortage. Today, I will discuss an important paper by Michael Kremer and Christopher Snyder. Kremer and Snyder argue that for the same cost and effectiveness drugs are more profitable to produce than vaccines. As a result, private incentives bias the market against vaccines.

A well known reason is that some people free rider on vaccine provision. When you are vaccinated, I benefit from one less possible transmitter. As a result, some who benefit do not pay. Drugs, in contrast, offer more excludable benefits thereby increasing demand and profits.

Drugs also provide a very natural method for firms to, in effect, price discriminate.

A simple example suffices to illustrate this point. Suppose there are 100 total consumers, ninety of whom have a ten percent chance of contracting the disease and ten of whom have a 100 percent chance. Suppose consumers are risk neutral and are willing to pay 100,000 to be cured of the disease if they contract it. A monopolist selling a vaccine could either charge 100,000 and sell to the ten high-risk consumers or charge 10,000 and sell to all 100 of them. Either way, the monopolist’s revenue is 1,000,000. A monopolist selling a treatment would, in expectation, sell to the nineteen consumers contracting the disease (all ten of the high risk consumers as well as an average of nine consumers from the low-risk group) at a price of 100,000 for a total revenue of 1,900,000, almost twice the revenue from a vaccine.

Damn, that’s clever. I wish I had thought of that.

Having praised Kremer and Snyder I now must say that I am not convinced that the forces they discuss matter very much. First, if the pharmaceutical market is competitive and vaccines pay then they will be produced even when drugs would be more profitable to a monopolist. K&S underestimate the competitiveness of the pharmaceutical market.

Second, my suspicion is that nature and science combine to make it the case that some diseases at some times are better treated by vaccines and other diseases by drugs. K and S’s model works best if there are many cases where drugs and vaccines are close cost-substitutes. Firms then choose drugs even when vaccines would have been more desirable. I think, in contrast, that cost differences will usually exceed the profit differences. On the margin, K and S are correct but suppose vaccines had been subsidized would we today have an AIDS vaccine? I doubt it.

I’m not necessarily against their conclusion, however, that vaccines should be subsidized relative to drugs. It’s sad to say, therefore, that as discussed yesterday we currently do precisely the opposite.

Is tit-for-tat the best strategy in games?

Remember tit for tat? I will cooperate if you do, but otherwise I defect. Many consider this to beeconsidered the best way to play in repeated prisoner dilemma situations. But the old wisdom is being revised:

…the Southampton team submitted 60 programs. These, Jennings explained, were all slight variations on a theme and were designed to execute a known series of five to 10 moves by which they could recognize each other. Once two Southampton players recognized each other, they were designed to immediately assume “master and slave” roles — one would sacrifice itself so the other could win repeatedly.

If the program recognized that another player was not a Southampton entry, it would immediately defect to act as a spoiler for the non-Southampton player. The result is that Southampton had the top three performers — but also a load of utter failures at the bottom of the table who sacrificed themselves for the good of the team…

Our initial results tell us that ours is an evolutionarily stable strategy — if we start off with a reasonable number of our colluders in the system, in the end everyone will be a colluder like ours,” he said.

This, by the way, is how the Soviets used to win chess tournaments. Throw games to the leading Soviet player, and fight especially hard against the leading non-Soviet rivals.

I have not seen the primary information on the games or the program, but I suspect that some caveats are in order. First, simulated game results usually are sensitive to the choice of parameter values. Second, this strategy may be appropriate for genetically-related teams, but otherwise it will not be implemented in the real world without side payments or coercion (both are typically prohibited in the game in question).

Here is the full story, which also provides useful background information for those new to this debate. And thanks to www.geekpress.com for the pointer.

What is the nature of American poverty?

Robert Samuelson is one of my favorite economics columnists:

Many middle-class families achieved large income gains in the 1990s and — despite the recession and halting recovery — have kept those gains. They’re worse because the increase in poverty in recent decades stems mainly from immigration. Until our leaders acknowledge the connection between immigration and poverty, we’ll be hamstrung in dealing with either.

Let’s examine the Census numbers. They certainly don’t indicate that, over any reasonable period, middle-class living standards have stagnated. Mostly, the middle class is getting richer. Consider: In 2003, 44 percent of U.S. households had before-tax incomes exceeding $50,000; about 15 percent had incomes of more than $100,000 (they’re included in the 44 percent). In 1990, the comparable figures were 40 percent and 10 percent. In 1980, they were 35 percent and 6 percent. All comparisons are adjusted for inflation.

True, the median household income has dropped since 1999 and is up only slightly since 1990. That’s usually taken as an indicator of what’s happened to a typical family. It isn’t. The median income is the midpoint of incomes; half of households are above, half below. The median household was once imagined as a family of Mom, Dad and two kids. But “typical” no longer exists. There are more singles, childless couples and retirees. Smaller households tend to have lower incomes. They drag down the overall median. So do more poor immigrant households.

A slightly better approach is to examine the incomes of households of similar sizes: all with, say, two people. In 2003 those households had a median income of $46,964, off about $900 from the peak year (1999) but up almost 10 percent from 1990. For four-person households, the median income in 2003 was $64,374, off about $2,200 from its peak but still up about 14 percent from 1990. Though unemployment and a decline in overtime have temporarily dented incomes, the basic trend is up.

Now look at poverty. For 2003, the Census Bureau estimated that 35.9 million Americans had incomes below the poverty line; that was about $12,000 for a two-person household and $19,000 for a four-person household. Since 2000 poverty has risen among most racial and ethnic groups. Again, that’s the recession and its aftermath.

But over longer periods, Hispanics account for most of the increase in poverty. Compared with 1990, there were actually 700,000 fewer non-Hispanic whites in poverty last year. Among blacks, the drop since 1990 is between 700,000 and 1 million, and the poverty rate — though still appallingly high — has declined from 32 percent to 24 percent. (The poverty rate measures the percentage of a group that is in poverty.) Meanwhile, the number of poor Hispanics is up by 3 million since 1990. The health insurance story is similar. Last year 13 million Hispanics lacked insurance. They’re 60 percent of the rise since 1990.

To state the obvious: Not all Hispanics are immigrants, and not all immigrants are Hispanic. Still, there’s no mystery here. If more poor and unskilled people enter the country — and have children — there will be more poverty. (The Census figures cover both legal and illegal immigrants; estimates of illegal immigrants range upward from 7 million.) About 33 percent of all immigrants (not just Hispanics) lack a high school education. The rate among native-born Americans is about 13 percent.

The bottom line: The American middle class is doing better than many commentators would have you believe. And while I don’t think we should neglect the welfare of Hispanics, in many cases the correct comparison is with their native countries, not with other U.S. statistical aggregates.

Addendum: Here is a good piece on how the federal government defines poverty.

Vaccines: The Short Run

President Bush was correct when he said that liability risk is one factor in the recurrent shortage of vaccines. Based on a post by Mark Kleiman, suggesting that flu vaccines are immune from liability due to the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, Brad De Long called Bush’s claim an “eternal lie.” To his credit, Kleiman (but not DeLong) quickly retracted his post when others pointed out that the VICP applies only to pediatric vaccines.

Liability is not the only issue, however. Costly FDA regulations and requirements, for example to remove thimerosal from vaccines despite no evidence of safety problems, have pushed firms out of the industry. See this paper in the The Independent Review (I am an assistant editor) for more on these regulations and their consequences.

A further problem is that the federal government is the major purchaser of vaccines, although not the flu vaccine, and it uses its monopsony powers and the law to require companies to sell at low prices. Firms have left the industry because they are squeezed on one end by regulation and on the other by low prices and, for vaccines like the flu vaccine not covered by VICP, potential liability. Note that even if the prices are high enough to earn the company a modest profit the point is that they are not high enough to make it worthwhile to make a surplus of vaccine that can be sold in the event of a contamination problem, as has happened this year. If the firms can’t price high during a shortage then there is no incentive to plan for a shortage.

Even without legal price caps there are significant disincentives to high prices. Here is a CDC spokesperson (link to audio file) on recent price increases:

Shame on the people who are price gouging. This is a reprehensible thing to be doing. I think an immoral thing.

Is it any wonder that firms don’t want in on this market?

Henry Miller, a former head of the FDA’s biotechnology division, summarizes well:

The fundamental problem is that government regulatory policies and what amounts to price controls discourage companies from investing aggressively to develop new vaccines. Producers have abandoned the field in droves….Although their social value is high, their economic value to pharmaceutical companies is low because of vaccines’ low return on investment and the exposure to legal liability they bring manufacturers….

Moreover, the FDA has a history of removing safe and effective vaccines from the market based merely on perceptions of excessive side effects — a prospect that terrifies manufacturers.

We need a fundamental change in mind-set: The rewards for creating, testing and producing vaccines must become commensurate with their benefits to society, as is the case for therapeutic pharmaceuticals.

Read Henry’s article for more on dealing with the problem today, (he notes, for example, that it may be possible to dilute current stocks and still maintain good effectiveness). Also, as Tyler reported last year, simply targeting vaccines to at-risk people is not necessarily the best approach. A better approach is to target super-spreaders, people who may not be at great risk themselves but who can and will spread it to many others.

Tomorrow: Vaccines: The Long Run.

Fastest Flip-Flop Ever?

Here from last night’s debate, is President Bush making a good case against government-run health care:

I think government- run health will lead to poor-quality health, will lead to rationing, will lead to less choice.

Once a health-care program ends up in a line item in the federal government budget, it leads to more controls.

And just look at other countries that have tried to have federally controlled health care. They have poor-quality health care.

Our health-care system is the envy of the world because we believe in making sure that the decisions are made by doctors and patients, not by officials in the nation’s capital.

And what does he say less than two minutes later?

We’ve increased VA funding by $22 billion in the four years since I’ve been president. That’s twice the amount that my predecessor increased VA funding.

Of course we’re meeting our obligation to our veterans, and the veterans know that.

We’re expanding veterans’ health care throughout the country. We’re aligning facilities where the veterans live now. Veterans are getting very good health care under my administration…

True, you can’t blame him much for the flip-flop – it’s what the public wants to hear. How many people even noticed the glaring contradiction? I suppose that on this issue I’d rather have flip-flop than all flop.

Prescott on Bush’s fiscal policy

Edward Prescott, who picked up the Nobel Prize for Economics, said President George W. Bush tax rate cuts were “pretty small” and should have been bigger.

“What Bush has done has been not very big, it’s pretty small,” Prescott told CNBC financial news television.

“Tax rates were not cut enough,” he said.

Lower tax rates provided an incentive to work, Prescott said.

As spoken, I agree with the words. But I must wonder if negative numbers count as “pretty small”? We all know that Bush has shifted taxes into the future, not cut them. Government spending is a better (albeit still imperfect) measure of what government takes from the economy. And domestic spending is way, way up; read Alex here.

We try to vary our content on MarginalRevolution; still if there were one point that we would make every day, it would be this one. “It’s the spending, stupid,” you might say.

Prescott should not be blamed for any possible misquotation or removal from context of his words by the news media; if there is any economist who understands the difference between real and nominal variables, or the importance of intertemporal budget constraints, it is he. Here is the link.

Markets in everything

Ms. Frenkel was not on a date with Mr. Blumberg, in pursuit of a kinky threesome; she was on the clock. A 29-year-old graduate student, she is one of a dozen women who work for a New York-based Web site called Wingwomen.com, earning up to $30 an hour to accompany single men to bars and help them chat up other women. The Web site’s founder, Shane Forbes, a computer programmer, started it in December after realizing he had more success with women when he went to clubs with female friends. “Every time I was with them, I would meet women,” he said.

I find that women often judge a husband by the quality of his wife. We call this a “sufficient statistic.”

But do Wingwomen work for everyone?

When asked about the women he had met, he shrugged. “They are all nice and cute, but two were in insurance, and the other one is from New Jersey.”

Here is the full story. Thanks to Andy for the pointer.

Addendum: Randall Parker discusses other possible dating strategies…don’t be shocked…

The virtues of a nasty central banker

The most important application of the time-consistency ideas in Kydland and Prescott’s work (with due credit going also to Barro and Gordon and Kenneth Rogoff) is to monetary policy. Consider a central bank that wants low inflation and low unemployment. To keep inflation low the central bank promises to hold down the growth rate of money. Let us suppose that the public believes the central bank’s promise and as a result they plan on low inflation in their writing of contracts. At some point, however, unemployment will increase and the central bank will be tempted to juice the economy with a spurt of inflation. Since the public has planned on low inflation a higher than expected inflation rate will be very effective at reducing unemployment and thus very tempting.

But the situation that I have just described cannot be a rational equilibrium. When the central bank promises to keep inflation low the public will say, ‘this promise isn’t credible – if we take the central bank at their word they will surely try to deceive us later with high inflation rates’. As a result, the public does not plan on low inflation and when the central bank does want to reduce unemployment it must increase inflation even more than when low inflation was expected. The only equilibrium of this game is one with high inflation and no systematic reduction in unemployment.

How can we improve the situation? Surprisingly, a nasty central banker can make everyone better off. A nasty central banker cares only about reducing inflation and not at all about reducing unemployment (think fat-cat Republican living off fixed income bonds). Precisely because a nasty central banker won’t juice the economy to reduce unemployment, the nasty central banker can credibly commit to keep inflation low. The public believes the promise and safely plans for low inflation. Unemployment is the same in both scenarios – because the central bank can never systematically surprise the public with higher than expected inflation – but inflation itself is lower with the nasty central banker and thus the public is better off.

Thomas Schelling once described a similar idea this way: If you are kidnapped who do you want in charge of the negotiations, your loving wife or your nasty ex-wife? Easy, right? But suppose that the kidnappers know in advance who will be in charge of the negotiations – now who do you want? See? Sometimes, nasty people do good things.

A Nobel for Real Business Cycles

Tyler has commented on the time-consistency problem so I will post on the other contribution for which Kydland and Prescott were awarded the Nobel, real business cycles. (I see now that Tyler also has a post on real business cycles – that guy is fast!.)

Recessions have almost always been thought of as a failure of market economies. Different theories point to somewhat different failures, in Keynesian theories it’s a failure of aggregate demand, in Austrian theories a mismatch between investment and consumption demand, in monetarist theories a misallocation of resource due to a confusion of real and nominal price signals. In some of these theories government actions may prompt the problem but the recession itself is still conceptualized as an error, a problem and a waste.

Kydland and Prescott show that a recession may be a purely optimal and in a sense desirable response to natural shocks. The idea is not so counter-intuitive as it may seem. Consider Robinson Crusoe on a desert island (I owe this analogy to Tyler). Every day Crusoe ventures onto the shoals of his island to fish. One day a terrible storm arises and he sits the day out in his hut – Crusoe is unemployed. Another day he wanders onto the shoals and he finds an especially large school of fish so he works long hours that day – Crusoe is enjoying a boom economy. Add to Crusoe’s economy some investment goods, nets for example, that take “time to build.” A shock on day one will now exert an influence on the following days even if the shock itself goes away – Crusoe begins making the nets when it rains but in order to finish them he continues the next day when it shines. Thus, Crusoe’s fish GDP falls for several days in a row – first because of the shock and then because of his choice to build nets, an optimal response to the shock.

An analogy is one thing but K and P showed that a model built from exactly the same microeconomic forces as in the Crusoe economy could duplicate many of the relevant statistics of the US economy over the past 50 years. This was a real shock to economists! There are no sticky prices in K & P’s model, no systematic errors or confusions over nominal versus real prices and no unexploited profit opportunities. A perfectly competitive economy with no deviations from classical Arrow-Debreu assumptions could/would exhibit behavior like the US economy.

Models like K & P’s called dynamic, stochastic, general equilibrium (DSGE) models are now the standard in macroeconomics but today they may also include demand side shocks and sticky prices as well as real shocks. Thus thesis has met anti-thesis and the synthesis has demand and supply shocks both contributing to business cycles.

Addendum: More at the Nobel site.

Why real business cycle theory is important

Most nineteenth century theories of the business cycle were real (non-monetary) in nature, often involving agricultural causes. The harvest is bad and next thing you know, the economy stands in ruins. A pretty good theory when agriculture accounts for more than half of gdp. The Swede Knut Wicksell stood at the peak of this tradition, although he used changes in the natural rate of interest as a more general way of thinking about the initial real shock. In the basic Wicksellian story, a decline in the real rate of return causes entrepreneurs to contract their economic activity. Money and credit contract as well, leading to a downward “cumulative process.”

Real business cycle theory to some extent went underground during the “years of high theory.” Both Hayek and Keynes, while they drew from Wicksell, diverted our attentions away from traditional real business cycle theory mechanisms. Hayek blamed monetary expansion, while Keynes focused more on issues of animal spirits and liquidity premia, and sometimes sticky prices. Kalecki and others worked on the real approach, but it lost its professional centrality.

The rational expectations revolution of the 1970s led us back to real approaches. If people anticipate the future with a fair degree of accuracy and rationality, money will likely be neutral or close to neutral. Furthermore if all markets clear, there should be no room for sticky prices and wages. So what else is left other than real theories of the business cycle?

Any business cycle theory, real or not, must account for at least two generalized phenomena of business cycles: persistence (the cycle is not over right away but rather drags on) and comovement (many sectors of the economy move together). Kydland and Prescott were among the first people to see this problem (kudos to Long, King, and Plosser as well), and among the first to address it.

Kydland and Prescott wrote a seminal article (Econometrica 1982) about “Time to Build and Aggregate Fluctuations.” They resurrected the old Austrian concept of a “period of production.” But rather than engaging in the metaphysics of capital theory, they ran some simulations. They showed that if production takes time, an initial negative shock can cause lower inputs and outputs over a longer period of time. Furthermore they showed that reasonable assumptions about parameter values can lead this mechanism to fit the real world. This article made an immediate splash, and rightly so.

Now today the purely real approach to business cycles no longer stands. Wage and price stickiness now play some role in virtually all business cycle theories, if only because labor market data otherwise appear inexplicable. But you might also say that today “we are all real business cycle theorists.” Most economists subscribe to a hybrid theory involving monetary shocks, real shocks, and imperfect adjustment mechanisms. All of these theories, to some extent or another, rely on the real transmission mechanisms outlined by Kydland, Prescott, and others.

Kydland and Prescott: New Nobel Laureates

This year’s Nobel Prize in economics went to Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott . Kydland and Prescott wrote a famous 1977 piece (Journal of Political Economy) on time inconsistency. Ever wonder why government policy toward prescription drugs is so problematic? Kydland and Prescott had the answer. The optimal policy will first award the drugmakers a patent and allow them to charge a high price. But once the drug is developed, the “rents” will be confiscated. Optimal policy will revoke the patent and lower the price. After all, once you have the drug. why not let everybody have it cheaply? Of course the drugmakers are aware of this danger in advance, and they are correspondingly reluctant to develop new drugs. Alex posted on this logic just days ago.

In more formal language, the optimal policy is not a time consistent policy. This develops earlier ideas from Thomas Schelling on game theory. Schelling’s point was that nuclear deterrence can fail because, once destruction is aimed your way, you don’t necessarily wish to retaliate.

The logic of time consistency is quite general. It applies to regulatory policy issues, tax policy, monetary policy, foreign policy (threaten Saddam, but do you really want to have go to through with it?), and strategic behavior in a wide variety of settings.

Here are my earlier comments on Prescott, which link to other facets of his work. He arguably has enough contributions to win the prize twice. Kydland is less well known but is an important figure nonetheless. And it doesn’t hurt that he is Scandinavian (Norwegian).

Are the pair deserving? Absolutely yes.

Why did they win this year? I’m guessing that in the midst of a partisan U.S. election, the Swedes did not want to pick Paul Krugman or Robert Barro (pro-Bush), for fearing of appearing too political. Note that the economics prize has stood under criticism for some time now, for not being “scientific” enough.

And this pick the betting market got right. Prescott had opened up a clear lead in the betting market some time ago.

If only it were true

George Bush during the second debate:

Non-homeland, non-defense discretionary spending was raising at 15 percent a year when I got into office. And today it’s less than 1 percent, because we’re working together to try to bring this deficit under control.

Kevin Drum makes it simple.

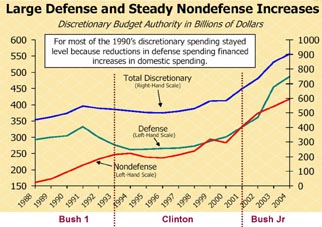

Here’s the truth about non-defense discretionary spending over the past six administrations:

Nixon/Ford: 6.8% per year

Carter: 2.0% per year

Reagan: -1.3% per year

Bush 1: 4.0% per year

Clinton: 2.5% per year

Bush Jr: 8.2% per year

All percentages are adjusted for inflation. The chart on the right shows raw figures for the past three administrations (from the Congressional Budget Office).

My goof

In my recent post on pharmaceutical regulation I wrote:

In the pharmaceutical market the major costs are all fixed costs (they don’t vary much with market size) so profit =P*Q-F. Acemoglu and Linn look at changes in Q but a 1% change in P has exactly the same effects on profits, and thus presumably on R&D, as a 1% change in Q.

But as Bernie Yomtov pointed out to me a reduction in P will increase Q. Ugh, an economist who has to be reminded about the law of demand. Embarrassing. The argument goes through if demand is quite inelastic which makes sense for a lot of drugs given that the price to the final consumer is low to begin with due to insurance – nevertheless the result is not so clean. Indeed, because of the envelope theorem a small change in P will have only a very small change in profits. Sadly, I teach this to my students regularly. Did I mention that I have had the flu this week?

Are asset price bubbles good?

“A bubble is good for growth because it creates a low cost environment for experimentation.”

Here is the full argument. I am prepared to believe that the government should not try to regulate or otherwise restrict bubbles. Why should we think that governments can outguess traders? And bubbles help finance socially worthwhile ideas that may not have high private returns. But would I wish that traders had less “bubbly” temperaments?

Thanks to www.politicaltheory.info for the link.

Markets in everything

Who needs an entire boyfriend, when you can have just one part? The Japanese have an answer to this question.

Thanks to Yana for the pointer.