Category: History

Sentences to ponder

The scientific method & capitalism are similarly inhuman systems. They also happen to be the primary sources of our progress.

That is Kebko, from the MR comments section.

Now is the Time for the Buffalo Commons

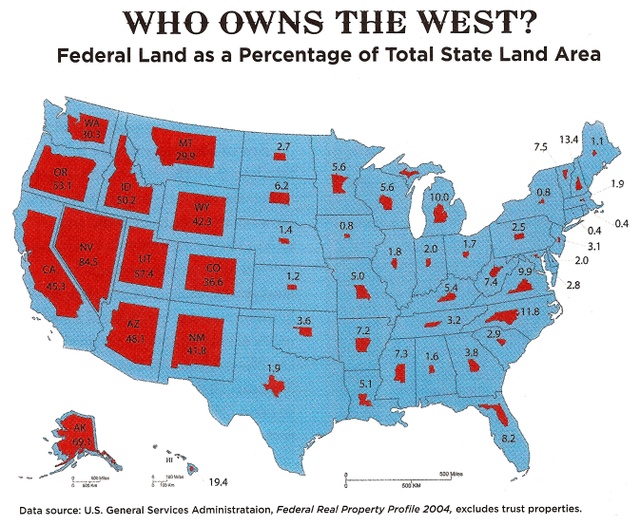

The Federal Government owns more than half of Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Idaho and Alaska and it owns nearly half of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Wyoming. See the map for more. It is time for a sale. Selling even some western land could raise hundreds of billions of dollars – perhaps trillions of dollars – for the Federal government at a time when the funds are badly needed and no one want to raise taxes. At the same time, a sale of western land would improve the efficiency of land allocation.

Does a sale of western lands mean reducing national parkland? No, first much of the land isn’t parkland. Second, I propose a deal. The government should sell some of its most valuable land in the west and use some of the proceeds to buy low-price land in the Great Plains.

The western Great Plains are emptying of people. Some 322 of the 443 Plains counties have lost population since 1930 and a majority have lost population since 1990.

Now is the time for the Federal government to sell high-priced land in the West, use some of the proceeds to deal with current problems and use some of the proceeds to buy low-priced land in the Plains creating the world’s largest nature park, The Buffalo Commons.

Hat tip to Carl Close for the pointer to the map.

What ended the Great Depression?

There has been recent circulation of the older view that it is World War II, as a kind of giant public works project, which ended the Great Depression. This claim is not consistent with our best knowledge of the subject. To survey the cutting edge of the literature briefly:

Christina Romer writes:

This paper examines the role of aggregate demand stimulus in ending the

Great Depression. A simple calculation indicates that nearly all of the

observed recovery of the U.S. economy prior to 1942 was due to monetary

expansion. Huge gold inflows in the mid- and late-1930s swelled the

U.S. money stock and appear to have stimulated the economy by lowering

real interest rates and encouraging investment spending and purchases

of durable goods. The finding that monetary developments were crucial

to the recovery implies that self-correction played little role in the

growth of real output between 1933 and 1942.

Here is another interesting paper on the topic; it focuses on productivity issues and mean reversion. Here is from a paper by Cullen and Fishback:

We examine whether local economies that were the centers of federal

spending on military mobilization experienced more rapid growth in

consumer economic activity than other areas. We have combined

information from a wide variety of sources into a data set that allows

us to estimate a reduced-form relationship between retail sales per

capita growth (1939-1948, 1939-1954, 1939-1958) and federal war

spending per capita from 1940 through 1945. The results show that the

World War II spending had virtually no effect on the growth rates in

consumption that we examined.

Further debunking of the WWII idea can be found in this paper by Robert Higgs, who stresses the difference between standard gdp measures and actual economic welfare.

I also find the experience of the Latin American economies convincing. The economic recovery of Argentina, for instance, clearly was due to monetary policy, not fiscal policy, which remained tight throughout the period of recovery. Mexico recovered from the Great Depression relatively quickly and this history also does not fit the fiscal policy view. Later on, most of the Latin economies experienced commodity booms because of wartime demands and again this was not fiscal policy and of course they were not fighting the war themselves. The two countries where fiscal policy played a significant role in recovery are, not surprisingly, Germany and Japan and here I am referring to their prewar spending.

Ben Bernanke on the New Deal

I’ve been rereading some of the essays in Ben Bernanke’s Essays on the Great Depression, which of course is self-recommending. I thought this passage summed up some relevant truths:

Our [with Martin Parkinson] own view is that the New Deal is better characterized as having "cleared the way" for a natural recovery (for example, by ending deflation and rehabilitating the financial system), rather than as being the engine of recovery itself.

Bernanke notes that there were "remarkably strong" productivity gains throughout much of the 1930s, even though there was no capital deepening. This is a central puzzle which any account of the New Deal, or New Deal recovery, must incorporate. These gains seem to span more sectors than could be accounted for by New Deal policy alone, and note that most government interventions, even good ones, don’t bring productivity gains over such a short time horizon and in such a regular and sustained fashion.

Bernanke does suggest that some of the gains came from forced unionization and "efficiency wage" effects and yes that would credit the New Deal. But I doubt that is the best hypothesis and of course it contradicts the traditional account of profit-seeking behavior from businesses (why weren’t they paying the higher wages in the first place?). Rick Szostak’s work suggests that the New Deal saw lots of labor-saving, process innovations, which meant both high productivity gains and pressure on labor markets at the same time. In my view most of these gains were simply the result of working through the implications of the earlier fundamental breakthroughs of the preceding twenty years.

Whatever is the case (and we genuinely don’t know), these productivity gains are central to the story of New Deal recovery. Roosevelt may deserve credit for some of them, or for allowing them to proceed, but don’t assume that the New Deal caused such gains just because you see them in the gross data.

You can find different drafts of the relevant Bernanke-Parkinson paper here, with various forms of gating.

Heroes and Cowards, part II

The single most important determinant of camp survival was the number of men in POW camps. If everyone had been in a camp holding 7,500 men, survival probabilities would have been less than 60 percent instead of more than 80 percent. With greater camp populations survival probabilities would have been even lower. Another important determinant of camp survival was age. Had all men been of Thomas Withington’s age (47), only 70 percent of them would have survived. The next most important determinants of camp survivial were the number of friends, rank, and height. Men who were not either commissioned or noncommissioned officers fared poorly, as did those with no friends and those of Hnery Haven’s height.

Of course that is from the Civil War and it is from the new book by Dora Costa and Matthew Kahn. Here is my previous post about the book, see also the links suggested by Matt in the comments. You can buy the book here.

Unemployment During the Great Depression

Regarding unemployment during the Great Depression, Andrew Wilson writing at the WSJ recently said:

As late as 1938, after almost a decade of governmental “pump priming,” almost one out of five workers remained unemployed.

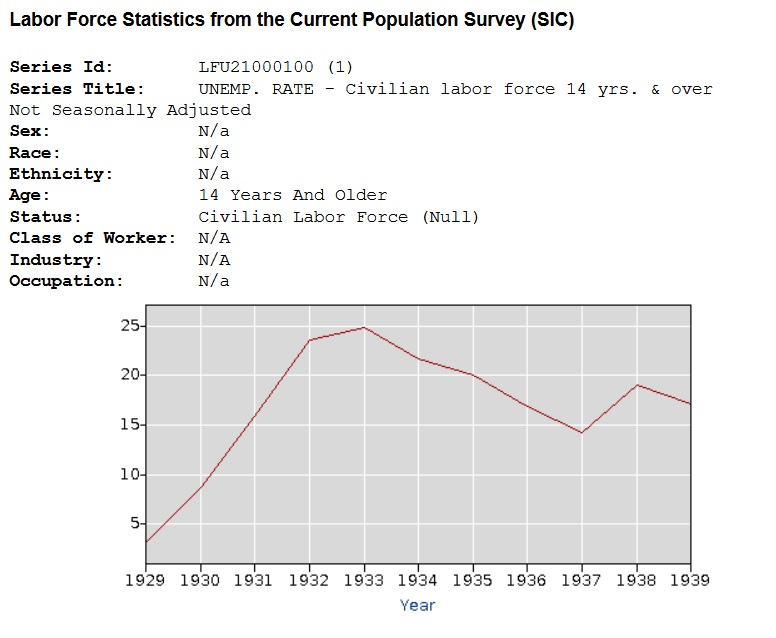

Historian Eric Rauchway says this is a lie, a lie spread by conservatives to besmirch the sainted FDR. Nonsense. In 1938 the unemployment rate was 19.1%, i.e. almost one out of five workers was unemployed, this is from the official Bureau of Census/Bureau of Labor Statistics data series for the 1930s. You can find the series in Historical Statistics of the United States here (big PDF) or here. The graph is at right. Rauchway knows this but wants to measure unemployment using an alternative series which shows a lower unemployment rate in 1938 (12.5%). Nothing wrong with that but there’s no reason to call people who use the official series liars.

Historian Eric Rauchway says this is a lie, a lie spread by conservatives to besmirch the sainted FDR. Nonsense. In 1938 the unemployment rate was 19.1%, i.e. almost one out of five workers was unemployed, this is from the official Bureau of Census/Bureau of Labor Statistics data series for the 1930s. You can find the series in Historical Statistics of the United States here (big PDF) or here. The graph is at right. Rauchway knows this but wants to measure unemployment using an alternative series which shows a lower unemployment rate in 1938 (12.5%). Nothing wrong with that but there’s no reason to call people who use the official series liars.

So why are there multiple series on unemployment for the 1930s? The reason is that the current sampling method of estimation was not developed until 1940, thus unemployment rates prior to this time have to be estimated and this leads to some judgment calls. The primary judgment call is what do about people on work relief. The official series counts these people as unemployed.

Rauchway thinks that counting people on work-relief as unemployed is a right-wing plot. If so, it is a right-wing plot that exists to this day because people who are on workfare, the modern version of work relief, are also counted as unemployed. Now if Rauchway wants to lower all estimates of unemployment, including those under say George W. Bush, then at least that would be even-handed but lowering unemployment rates just under the Presidents you like hardly seems like fair play.

Moreover, it’s quite reasonable to count people on work-relief as unemployed. Notice that if we counted people on work-relief as employed then eliminating unemployment would be very easy – just require everyone on any kind of unemployment relief to lick stamps. Of course if we made this change, politicians would immediately conspire to hide as much unemployment as possible behind the fig leaf of workfare/work-relief.

There is a second reason we may not want to count people on work-relief as employed and that is if we are interested in the effect of the New Deal on the private economy. In other words, did the fiscal stimulus work to restore the economy and get people back to work? Well, we can’t answer that question using unemployment statistics if we count people on work-relief as employed. Notice that this was precisely the context of the WSJ quote.

One final thing that one could do is count people on work-relief as neither employed nor unemployed, i.e. not part of the labor force which is what we do for people in the military. Rauchway has data on this and it shows almost the same thing, nearly one in five unemployed, as the original series. (In this case, however, Rauchway counts nearly one in five unemployed as a win for the New Deal because the same series also shows higher unemployment earlier in the Great Depression.)

Any way you slice it there is no right-wing plot to raise unemployment rates during the New Deal and a historian should not go around calling people liars just because their judgment offends his wish-conclusions.

Hat tip to Mark Thoma.

Heroes and Cowards: The Social Face of War

Company socioeconomic and demographic diversity was the single most important predictor of desertion [in the Civil War].

Age and occupational diversity were especially important. For all-black regiments, former slave status (or not) and plantation of origin are important diversity measures for predicting desertion.

That is from the forthcoming book by Dora L. Costa and Matthew E. Kahn. I have not yet finished it but I believe this book will make a big splash. Here is the book’s home page. Here is a blog post by Matt Kahn on the book. Here is Matt Kahn on holding hands.

Europe Between the Oceans

Can you say longue durée? If so (or if not), here’s the new book by Barry Cunliffe, with the subtitle 9000 B.C.-AD 1000 indicating a coverage of murky yet critical millennia.

It’s a history of Europe which blends economic geography and economic archaeology. The underlying question is how Europe became so innovative and the answer has much to do with trade and migration. Imagine a more balanced and grounded Braudel. The explanation of the "Neolithic package" and its spread across Europe is stunning. I loved it when the author broke away from a passage about Phoenician trade routes to explain some odd lines in Homer. If you are wondering, Cunliffe is a moderate neo-migrationist. The photography and the color plates of the art are lovely. You can learn how to view the Roman Empire as an "interlude" and as a break from the major story and how to understand 800-1000 A.D. as a period of rebalancing. And you get passages like this:

…the actual return in calorific value for the effort expended in collecting [shellfish] is comparatively small. A single red deer would be worth fifty thousand oysters! That said, the value of shellfish is that they are always available and can be substituted when other food sources run short.

If you enjoy early economic history, this is a must, noting that it does not have the titillating feel of a popular science book. It is my pick for best non-fiction book of the year so far.

Here is the book’s home page. Here is one short review. Here is a Times review. You can buy an excellent long review (LRB) here.

Buy the book here (at $26 the per page price is low) to learn why economic archaeology should win a Nobel Prize someday.

The Rise of Mutual Funds

Investors preferred closed-end funds to mutual funds because closed-end funds offered the possibility of greater returns due to their use of leverage and the history of their shares trading at premiums.

That’s about the 1920s. It is from Matthew P. Fink’s quite interesting and useful The Rise of Mutual Funds: An Insider’s View.

Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics

That’s the title of the new book by Yasheng Huang. This very serious work reexamines the role of the state in the Chinese economy. It suggests that the Chinese private sector has been more productive than claimed, China fits the traditional theory of property rights and incentives more than is often realized, the Chinese economy is not necessarily getting freer, market ideas are strongest in rural China, rural China was reregulated in an undesirable way starting in the early 1990s, the "Shanghai miracle" is overrated, when you calculate the size of the private sector in China it matters a great deal whether you use input or output measures, and China may collapse into crony capitalism rather than following the previous lead of Korea and Japan.

The dissection of Joseph Stiglitz on China, starting on p.68, is remarkable.

I do not have the detailed knowledge to evaluate all of these claims but in each case the author offers serious evidence and arguments. This book does not make for light reading (though it is clearly written), but it is quite possibly the most important economics so far this year. Here is a good review from The Economist.

The Big Necessity

I can’t decide if that is a very good or a very bad title. Nonetheless the book itself is excellent. The author, Rose George, stresses:

To be uninterested in the public toilet is to be uninterested in life.

You also learn that toilets may have saved more lives than any other human invention, public toilets are disappearing in London and many other cities, and that many Kenyans have "helicopter toilets," which start with the use of a plastic bag. My favorite moment in the book is this:

After five hours of my questions, Mr. Tanaka shyly offers two of his own: "Why don’t English people want high-function toilet? Why is Japan so unique?"

Definitely recommended and yes it is a serious book too.

The Partnership

For the proud Sachs family, the failure of Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation became a very public humiliation. In 1932, Eddie Cantor, the popular comedian and one of forty-two thousand investors in Goldman Sachs trading Corporation, sued Goldman Sachs for one hundred million dollars while regularly including in his vaudeville routine bitter jokes about the firm. One: "They told me to buy the stock for my old age…and it worked perfectly…Within six months, I felt like a very old man!"

That is from the new Charles D. Ellis book The Partnership: The Making of Goldman Sachs. So far this book is a very good history and it has more economic and historic substance than The Snowball.

Sentences to ponder

Call it the biggest carry trade in history.

Here is more.

In case you had forgotten

SOX [Sarbanes-Oxley] was sold as the way to prevent future market bubbles and crashes.

That’s Larry Ribstein reminding us. And here is Arnold Kling reminding us:

A Central Banker should stand up to fear-mongering. Even when it comes from a Treasury Secretary.

And here is Robin Hanson reminding us of his favorite lessons:

Medicine isn’t about Health

Consulting isn’t about Advice

School isn’t about Learning

Research isn’t about Progress

Politics isn’t about Policy

How big was the Nazi premium?

Every now and then I like to post about history:

Firms connected with the Nazi party outperformed unaffiliated firms

massively. Their share prices rose by 7.2% between January and March

1933 (43% annualised), compared to 0.2% (1.2% annualised) for

unaffiliated firms. The politically induced change was equivalent to

5.8% of total market capitalisation. This is a high number by

international standards. Johnson and Mitton (2003) estimate that

revaluation of political connections in Malaysia during the East Asian

crisis wiped 5.8% of share values. While comparable in magnitude, it

took 12 months for this change to occur.

Here is more, interesting throughout.