Category: Law

Intrade Traffic Plummets

From the FT

The number of people using Intrade has plummeted since a US government crackdown late last year…At its peak, Intrade counted 112,000 users. At midday on Wednesday, the site said there were 509 – and 498 were guests.

The vanishing traffic raises questions about the predictive value of a market feted by journalists and academics as a pioneering gauge of public opinion.

The government failed to protect the public from CDOs plumped up with bad mortgages or from swindlers like Bernie Madoff but don’t worry when it comes to the markets that Arrow, Schelling, Smith, Hanson, Wolfers et al. said have “great potential for improving social welfare” the government has got it covered. Call me cynical but I suspect Intrade would have been better treated had it been a project of Goldman Sachs.

Aviation, Liability Law, and Moral Hazard

In 1994, however, Congress passed GARA, the General Aviation Revitalization Act. GARA said that small airplane manufacturers could not be held liable for accidents involving aircraft more than 18 years old. When it was passed a huge stock of potential liability claims were lifted from the manufacturers and the industry was indeed revitalized. GARA also provided an interesting test of moral hazard theory. Usually, when liability is moved from producers to consumers, both the producers and the consumers adjust; the product changes and so does behavior, so it is difficult to parse out the effect of moral hazard alone. In the case of GARA, however, liability was lifted from the manufacturers on planes that they had produced decades earlier and no longer controlled so we can isolate the influence of the liability change on the consumers of aircraft.

My latest paper (with Eric Helland) just appeared in the JLE. We use the exemption at age 18 to estimate the impact of tort liability on accidents as well as on a wide variety of behaviors and safety investments by pilots and owners. Our estimates show that the end of manufacturers’ liability for aircraft was associated with a significant (on the order of 13.6 percent) reduction in the probability of an accident. The evidence suggests that modest decreases in the amount and nature of flying were largely responsible. After GARA, for example, aircraft owners and pilots retired older aircraft, took fewer night flights, and invested more in a variety of safety procedures and precautions, such as wearing seat belts and filing flight plans. Minor and major accidents not involving mechanical failure—those more likely to be under the control of the pilot—declined notably.

GARA thus appears to be a win-win because it revitalized the industry and increased safety. The latter came, in a sense, at the expense of the pilots and owners who now bore a greater liability burden but they were the least cost avoiders of accidents. Moreover, the pilots and owners of small aircraft were big supporters of GARA thus suggesting strongly that prior to GARA liability law for aircraft had been inefficient and destructive.

Economic agents ponder the collapse of the pooling equilibrium

Robert Pear reports:

“The new health care law created powerful incentives for smaller employers to self-insure,” said Deborah J. Chollet, a senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research who has been studying the insurance industry for more than 25 years. “This trend could destabilize small-group insurance markets and erode protections provided by the Affordable Care Act.”

It is not clear how many companies have already self-insured in response to the law or are planning to do so. Federal and state officials do not keep comprehensive statistics on the practice.

Self-insurance was already growing before Mr. Obama signed the law in 2010, making it difficult to know whether the law is responsible for any recent changes. A study by the nonpartisan Employee Benefit Research Institute found that about 59 percent of private sector workers with health coverage were in self-insured plans in 2011, up from 41 percent in 1998.

And:

Large employers with hundreds or thousands of employees have historically been much more likely to insure themselves because they have cash to pay most claims directly.

Now, employee benefit consultants are promoting self-insurance for employers with as few as 10 or 20 employees.

And from the FT:

The penalty for not providing coverage is $2,000 per worker. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a non-partisan policy group, the average annual cost to employers of insurance is $4,664 for a single worker and $11,429 for a family.

(Do note that the worker will find the job less attractive without health insurance., so this may not translate into a net gain for the employer.)

Here is an update on the 50% premium that can be charged to smokers, assuming the repeal movement for that feature does not succeed.

And now let me stress that you should not expect salvation from the (stand-alone) private sector. DNA sequencing seems to be making real progress, which will make private solutions harder to sustain, a problem which Alex pioneered the analysis of.

Addendum: Here is a good Christensen, Flier, and Vijayaraghavan Op-Ed on ACOs and their problems.

“Is wealth a value?”

Ronald Dworkin has passed away at age 81

Here is one brief account. There is more here (an excellent obituary). His works are worthy of close study.

An EU-U.S. trade pact?

I do favor the idea, but the bottom line is more likely this:

…[it] would require Europe to open farm, service and other markets that it has been slow to deregulate.

…U.S. officials have been concerned that Europe’s complex politics — of the 27 EU nations, some are avowed free-trade supporters while some veer towards protectionist industrial policy — would make for protracted and perhaps futile negotiations.

The letter from the two senators is a reminder of just how difficult an agreement would be. Goods already flow freely between the United States and the E.U. Much of the value of a free-trade pact would come through reducing regulatory red tape so that — for example — the two sides would adopt common policies on food safety, pharmaceutical testing, patents and other complex regulatory issues.

We cannot deregulate our own country, and yet we think we can deregulate a hydra-headed, 27-nation negotiating sclerotic behemoth? The big lure here is that the larger EU companies could access government procurement contracts in much of the U.S., but I don’t see that as a political trump by any means, most of all in the smaller countries. And what is the chance that the U.S. wins concessions only by adopting, in some cases, tougher regulatory policies (in the inappropriate and sclerotic sense)? Might this in some cases, through perhaps the magic of public choice theory, evolve into a regulatory cartel?

Nonetheless, as mentioned above, I’m all for trying.

*Sharing the Prize*

That is the new and much awaited book by Gavin Wright, with the subtitle The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South. Here is one small bit, reflecting some of the book’s main themes:

By the 1930s, labor markets in the South had come to display a distinct “racial wage gap,” supported by systems of vertical workplace segregation. Not only were job categories classified by race, but black wage rates typically peaked about where white pay grades began. These structures persisted through World War II and the 1950s, showing few signs of softening even in the presence of rapid urbanization and industrial employment growth.

Here are some related powerpoints by Wright (pdf). Here is the book’s home page.

Torture in a Just World

If the world is just, only the guilty are tortured. So believers in a just world are more likely to think that the people who are tortured are guilty. Perhaps especially so if they experience the torture closely and so feel a greater need to overcome cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, those farther away from the experience of torture may feel less need to justify it and they may be more likely to identify the tortured as victims. The theory of moral typecasting suggests that victims are also more likely to be seen as innocents (a la Jesus).

If the world is just, only the guilty are tortured. So believers in a just world are more likely to think that the people who are tortured are guilty. Perhaps especially so if they experience the torture closely and so feel a greater need to overcome cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, those farther away from the experience of torture may feel less need to justify it and they may be more likely to identify the tortured as victims. The theory of moral typecasting suggests that victims are also more likely to be seen as innocents (a la Jesus).

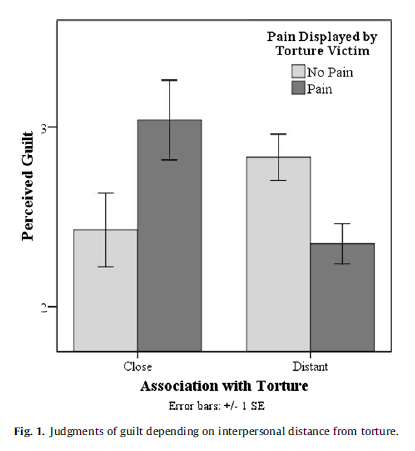

The theory is tested in a lab setting by Gray and Wegner. Experimental subjects are told that “Carol”, really a confederate, may have lied about a dice roll and that stress often encourages people to admit guilt. Subjects then listen to a torture session as Carol’s hand is plunged into a bucket of ice water for 80s. Subjects are then asked how likely is it that the torture victim was lying (1 to 5 with 5 being extremely likely). There are two intervention variables: 1) some of the subjects meet the torture victim before she is tortured, this is the close condition and some do not (distance condition) and 2) in some torture sessions the victim evinces pain (pain) and in others not (no pain). The key figure is shown below:

The most striking result is that in the close condition, the evincing of pain was associated with an increased judgment of guilt, consistent with torture causing cognitive dissonance which is relieved by a judgment of guilt (restoring the just world). But in the distance condition, the evincing of pain was associated with a decreased judgement of guilt, consistent with pain increasing the identification of the tortured as a victim and therefore innocent (a la moral typecasting).

The most striking result is that in the close condition, the evincing of pain was associated with an increased judgment of guilt, consistent with torture causing cognitive dissonance which is relieved by a judgment of guilt (restoring the just world). But in the distance condition, the evincing of pain was associated with a decreased judgement of guilt, consistent with pain increasing the identification of the tortured as a victim and therefore innocent (a la moral typecasting).

Closeness in the experiment was reasonably literal but may also be interpreted in terms of identification with the torturer. If the church is doing the torturing then the especially religious may be more likely to think the tortured are guilty. If the state is doing the torturing then the especially patriotic (close to their country) may be more likely to think that the tortured/killed/jailed/abused are guilty. That part is fairly obvious but note the second less obvious implication–the worse the victim is treated the more the religious/patriotic will believe the victim is guilty.

The theory has interesting lessons for entrepreneurs of social change. Suppose you want to change a policy such as prisoner abuse (e.g. Abu Ghraib) or no-knock police raids or the war on drugs or even tax policy. Convincing people that the abuse is grave may increase their belief that the victim is guilty. Instead, you want to do one of two things. Among the patriotic you may want to sell the problem as a minor problem that We Can Fix – making them feel good about both the we and the fixing. Or, you may want to create distance – The problem is bad and THEY are the cause. People in the North, for example, became more concerned about slavery once the US became us and them.

I think research in moral reasoning is important because understanding why good people do evil things is more important than understanding why evil people do evil things.

Sentences about coal

Europe’s use of the fossil fuel spiked last year after a long decline, powered by a surge of cheap U.S. coal on global markets and by the unintended consequences of ambitious climate policies that capped emissions and reduced reliance on nuclear energy.

…In Germany, which by some measures is pursuing the most wide-ranging green goals of any major industrialized country, a 2011 decision to shutter nuclear power plants means that domestically produced lignite, also known as brown coal, is filling the gap . Power plants that burn the sticky, sulfurous, high-emissions fuel are running at full throttle, with many tallying 2012 as their highest-demand year since the early 1990s. Several new coal power plants have been unveiled in recent months — even though solar panel installations more than doubled last year.

Here is more.

And first they came for the law professors…

Last week, it was reported that law school applications were on pace to hit a 30-year low, a dramatic turn of events that could leave campuses with about 24 percent fewer students than in 2010. Young adults, it seems, have fully absorbed the wretched state of the legal job market.

Good sentences about fashion and copying

The mass copying of a style is what creates a trend, and trends sell clothes today. This is why many in the industry furiously protect their right to ripping each other off. Two law professors, Kal Raustiala and Chris Sprigman, have argued against the design piracy act on the grounds that the American apparel industry “may actually benefit” from copying, as it speeds up the creation and exhaustion of trends.

Note the clever assignment of the externality. Rapid copying is needed for customers to develop the expectation that trends come and go rapidly, and thus to get customers to visit the store and buy today. Yet no single business will invest enough on its own in creating these broader expectations, because the industry as a whole reaps the benefit. The “copying game” induces the sellers to, in essence, act collusively to help establish these “hurry up and buy now” expectations.

The quotation is from Elizabeth L. Cline’s Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, which I quite enjoyed reading, despite some glaring weaknesses when it comes to FDI, wages, and foreign development. I now understand the affordable yet fashionable clothing stores in Tysons Corner Mall, and how they have changed over the last fifteen years, and I can thank this book for that.

Will health insurance premia rise for young males?

I suspect the analysis cited in this article is an exaggeration, but it is even more than I thought the exaggeration would be:

The survey, fielded by the conservative American Action Forum and made available to POLITICO, found that if the law’s insurance rules were in force, the premium for a relatively bare-bones policy for a 27-year-old male nonsmoker on the individual market would be nearly 190 percent higher.

…Insurers have been reluctant to share their premium projections for a variety of reasons, but Holtz-Eakin, through a lawyer intermediary, was able to get aggregated, anonymous data under a nondisclosure agreement. On average, premiums for individual policies for young and healthy people and small businesses that employ them would jump 169 percent, the survey found.

Note that subsidies would cushion such price shocks for lower-income individuals and that the premia for older and less healthy people would fall, by twenty-two percent according to a comparable estimate (do not forget that a smaller percentage figure is being applied to a larger absolute number). From a distance, it is difficult to judge how realistic these projections are.

Still, I would think that the chance of younger individuals refusing to adhere to the mandate is higher than Massachusetts-linked projections have been indicating.

I would say that in recent times there has been a string of bad news about ACA and few new reported items of good news.

Addendum, from the comments, from Carl the Econ Guy:

The whole survey is here:

http://americanactionforum.org/sites/default/files/AAF_Premiums_and_ACA_Survey.pdf

Look at Table 1– where it says that the average premium for young healthy males will go from $2,000 to a little over $5,000. Yikes.

A simple macro model of collateral

Regulators are pushing for non-centrally cleared trades to be backed by high levels of collateral, such as cash or government bonds. This is where the $10tn figure comes in. It is the amount of extra collateral that could be required according to estimates by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

Here is the full FT article. It stresses that figure of ten trillion may be too high an estimate, but a separate lower estimate still runs at $2 to $4 trillion.

Let’s play out the scenario. In some future world, what if most savings is done by corporations and also by traders at the clearinghouse, in the form of collateral. Collateral, however, is not “smoothed” across assets but rather is an either/or decision. They won’t take your sheepdog as collateral, nor will they take shares in small tech companies. Most of the saving is done in the form of approved safe assets and the rest of the economy is somewhat starved for investment.

I call it the return of financial repression. Let’s see how far it is allowed to go.

Our drone future?

(In case you’re worried that drones lack allies in Congress, rest easy: there’s a Congressional Unmanned Systems Caucus with 60 members. With global spending on drones expected to nearly double over the next decade, to $11.3 billion, industry groups like the AUVSI are rapidly ramping up their lobbying budgets.)

And:

Singer estimates that there are 76 other countries either developing drones or shopping for them; both Hizballah and Hamas have flown drones already. In November, a Massachusetts man was sentenced to 17 years for plotting to attack the Pentagon and the Capitol with remote-controlled planes.

The very interesting article is here, by Lev Grossman at Time, hat tip goes to The Browser.

*Shylock on Trial: The Appellate Briefs*

That is the new eBook by Richard Posner and Charles Fried, and I just bought my copy and expect I will be adding it to my Law and Literature syllabus. The book’s home page is here.

A longer book, edited by Bradin Cormack, Marthua Nussbaum, and Richard Strier will be coming out as well, Shakespeare and the Law, containing this piece among others.