Category: Medicine

Facts about Medicare

I’ve got a modest proposal: You’re not allowed to demand a “serious conversation” over Medicare unless you can answer these three questions:

1) Mitt Romney says that “unlike the current president who has cut Medicare funding by $700 billion. We will preserve and protect Medicare.” What happens to those cuts in the Ryan budget?

2) What is the growth rate of Medicare under the Ryan budget?

3) What is the growth rate of Medicare under the Obama budget?

The answers to these questions are, in order, “it keeps them,” “GDP+0.5%,” and “GDP+0.5%.”

Let’s be very clear on what that means: Ryan’s budget — which Romney has endorsed — keeps Obama’s cuts to Medicare, and both Ryan and Obama envision the same long-term spending path for Medicare. The difference between the two campaigns is not in how much they cut Medicare, but in how they cut Medicare.

That is from Ezra Klein, and here is further comment.

The wisdom of Miles Kimball

Don’t have a health care entitlement with no defined amount of money attached. Choose a $ figure and see what we can do with it.

As long as we precommit to lower health care spending by the government, it’s great to hope that comes from pushing prices down.

Those are both from Twitter, and here is a concordance of more of the tweets. I have myself toyed with this idea from Miles:

How about a new model: free clinics for all we can afford. People on their own for the rest. No employer insurance deduction.

Some raw numbers on health care costs

During the past months, a number of important articles have appeared in the healthcare literature on the subject of the recent slowing of health-spending growth in the U.S. In an article in January’s Health Affairs, economists at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services suggest that the recession, even though officially ending in mid-2009, was the major factor in “extraordinarily slow” spending growth of 4.7 percent in 2008 and 3.9 percent in 2010, down from 7.5 percent in 2007 and double-digit growth in the 1980s and 1990s. Also citing recessionary causes, a report from the McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform specifies declines in the rate of overall spending growth for eight consecutive years, from 9.2 percent in 2002 to 4.0 percent in 2009.

As I’ve already mentioned, “too soon to tell” is the correct response. Still, we should be raising our probability that the health care cost curve is (somewhat) being bent.

There is much more at the link. You can read Suderman and Lowrey here.

Are health care costs really slowing down?

Sarah Kliff writes:

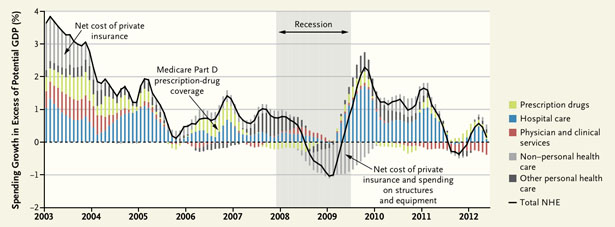

The New England Journal of Medicine published a paper this week titled “When the Cost Curve Bent,” where researchers from the Center for Sustainable Health Costs suggest that the slowdown happened way before the recession. Their analysis shows — and you can see it in this chart — that excess health-care spending growth (any spending above and beyond potential gross domestic product) began to moderate in the early 2000s:

“Too soon to say” is a fair enough response, but this has become increasingly my view over the last year.

Addendum: Angus comments.

The Medicaid wars continue

Sandra Decker, an economist with the Center for Disease Controls, recently poured over the 2011 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which asks doctors whether they would accept new Medicaid patients.

What she found could spell trouble for the health care law: More than three in ten doctors – 31 percent – said no, they would not.

Her research, published this afternoon in the journal Health Affairs, is the first that has ever given a state-by-state look at doctors’ willingness to accept Medicaid.

The problem, of course, is that higher demand will be pressing against a relatively fixed supply.

An event study of ACA winners and losers

I have not had the chance to read through this paper, by Jonathan Hartley, but thought I should pass along the abstract and link:

Abstract:

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 marked a substantial shift in US healthcare policy. We create an event study observing the returns of healthcare stocks in the S&P 500 when on June 28, 2012 the US Supreme Court very unexpectedly ruled that the individual mandate, a provision requiring that Americans maintain a certain level of health insurance or face a monetary penalty, was not unconstitutional. The paper finds that as a result of the upheaval, over two days following the ruling the cumulative average abnormal return of managed care stocks was -6.7% (equal to -$6.9 bn in market capitalization), while the same metric was -1.2% (-$1.5 bn) for biotechnology companies, 3.2% ($0.4 bn) for hospital firms, 1.9% ($1.6 bn) for healthcare service firms, and 0.5% ($4.8 bn) for pharmaceutical companies. Healthcare equipment, distribution, and technology sub-industry stocks had relatively flat cumulative abnormal returns over the period.

Do those results make you more or less favorable toward ACA?

Medicaid wars, continuing

Phil Galewitz and Matthew Fleming surveyed all 50 states to find out how Medicaid budgets are changing. They found that 13 states had made cuts this year..Seven have Democratic governors; six are led by Republicans. Three are in the south and an equal number are in New England. Two, California and Connecticut, seem to really like the Medicaid program: They volunteered to start the health law’s Medicaid expansion early, well before it’s required in 2014. Others, like Louisiana and Florida, are not fans at all: They plan to sit out that Obamacare provision.

All told, it’s pretty hard to find any narrative that explains why these states have cut their Medicaid programs, aside from some broad truths: Budgets are still squeezed and Medicaid is eating up a growing chunk of state spending.

From Sarah Kliff, here is more.

Pharmaceutical innovation is very, very good

We examine the impact of pharmaceutical innovation, as measured by the vintage of prescription drugs used, on longevity, using longitudinal, country-level data on 30 developing and high-income countries during the period 2000-2009. We control for fixed country and year effects, real per capita income, the unemployment rate, mean years of schooling, the urbanization rate, real per capita health expenditure (public and private), the DPT immunization rate, HIV prevalence and tuberculosis incidence. Life expectancy at all ages and survival rates above age 25 increased faster in countries with larger increases in drug vintage. The increase in drug vintage was the only variable that was significantly related to all of these measures of longevity growth. Controlling for all of the other potential determinants of longevity did not reduce the vintage coefficient by more than 20%. Pharmaceutical innovation is estimated to have accounted for almost three-fourths of the 1.74-year increase in life expectancy at birth in the 30 countries in our sample between 2000 and 2009, and for about one third of the 9.1-year difference in life expectancy at birth in 2009 between the top 5 countries (ranked by drug vintage in 2009) and the bottom 5 countries (ranked by the same criterion).

CBO forecasts Medicaid Wars

In 2022, for example, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are expected to cover about 6 million fewer people than previously estimated, about 3 million more people will be enrolled in exchanges, and about 3 million more people will be uninsured…

Only a portion of the people who will not be eligible for Medicaid as a result of the Court’s decision will be eligible for subsidies through the exchanges. According to CBO and JCT’s estimates, roughly two-thirds of the people previously estimated to become eligible for Medicaid as a result of the ACA will have income too low to qualify for exchange subsidies, and roughly one-third will have income high enough to be eligible for exchange subsidies.

There is more here.

The future of the war on drugs

At the same time, one branch of that thinking has itself evolved into a new project: the notion of creating downloadable chemistry, with the ultimate aim of allowing people to “print” their own pharmaceuticals at home. Cronin’s latest TED talk asked the question: “Could we make a really cool universal chemistry set? Can we ‘app’ chemistry?” “Basically,” he tells me, in his office at the university, with half a grin, “what Apple did for music, I’d like to do for the discovery and distribution of prescription drugs.”

Here is more, hat tip goes to the excellent Eli Dourado.

There Will Be Blood

Economists often reduce complex motivations to simple functions such as profit maximization. Writing in The Economist, Buttonwood ably criticizes such simplifications. Buttonwood is too quick, however, to conclude that simplification falsifies. For example, Buttonwood argues:

If there is a shortage of blood, making payments to blood donors might seem a brilliant idea. But studies show that most donors are motivated by an idea of civic duty and that a monetary reward might actually undermine their sense of altruism.

As loyal readers of this blog know, however, the empirical evidence is that incentives for blood donation actually work quite well. Mario Macis, Nicola Lacetera, and Bob Slonim, the authors of the most important work on this subject (references below), write to me with the details:

The decision to donate blood involves complex motivations including altruism, civic duty and moral responsibility. As a result, we agree with Buttonwood that in theory incentives could reduce the supply of blood. In fact, this claim is often advanced in the popular press as well as in academic publications, and as a consequence, more and more often it is taken for granted.

But what is the effect of incentives when studied in the real world with real donors and actual blood donations?

We are unaware of a single study of real blood donations that shows that offering an incentive reduces the overall quantity or quality of blood donations. From our two studies, both in the United States covering several hundred thousand people, and studies by Goette and Stutzer (Switzerland) and Lacetera and Macis (Italy), a total of 17 distinct incentive items have been studied for the effects on actual blood donations. Incentives have included both small items and gift cards as well as larger items such as jackets and a paid-day off of work. In 16 of the 17 items examined, blood donations significantly increased (and there was no effect for the one other item), and in 16 of the 17 items studied no significant increase in deferrals or disqualifications were found. No study has ever looked at paying cash for actual blood donations, but several of the 17 items in the above studies involve gift cards with clear monetary value.

Although many lab studies and surveys have found differing evidence focusing on other outcomes than actual blood donations (such as stated preferences), the empirical record when looking at actual blood donations is thus far unambiguous: incentives increase donations.

Given the vast and important policy debate regarding addressing shortages for blood, organ and bone marrow in developed as well as less-developed economies, where shortages are especially severe, it is important to not only consider more complex human motivations, but to also provide reliable evidence, and interpret it carefully. The recent ruling by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals allowing the legal compensation of bone marrow donors further enhances the importance of the debate and the necessity to provide evidence-based insights.

Here is a list of references:

Goette, L., and Stutzer, A., 2011: “Blood Donation and Incentives: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” Working Paper.

Lacetera, N., and Macis, M. 2012. Time for Blood: The Effect of Paid Leave Legislation on Altruistic Behavior. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, forthcoming.

Lacetera N, Macis M, Slonim R 2012 Will there be Blood? Incentives and Displacement Effects in Pro-Social Behavior. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4: 186-223.

Lacetera N, Macis M, Slonim R.: Rewarding Altruism: A natural Field Experiment, NBER working paper.

Firefighters Don’t Fight Fires

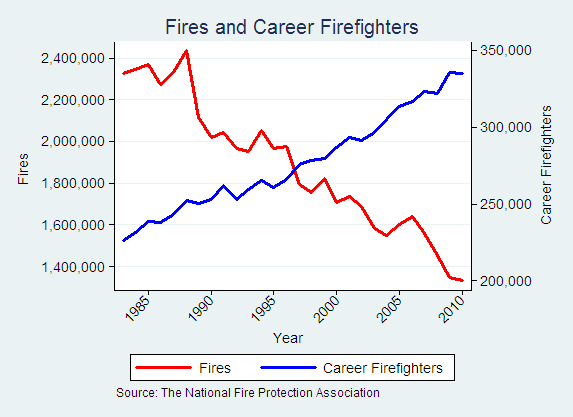

Over the past 35 years, the number of fires in the United States has fallen by more than 40% while the number of career firefighters has increased by more than 40% (data).

(N.B. Volunteer firefighters were mostly pushed out of the big cities in the late 19th century but there are a surprising number who remain in rural areas and small towns; in fact, more in total than career firefighters. The number of volunteers has been roughly constant and almost all of them operate within small towns of less than 25,000. Thus, you can take the above as approximating towns and cities of more than 25,000.)

The decline of demand has created a problem for firefighters. What Fred McChesney wrote some 10 years ago is even more true today:

Taxpayers are unlikely to support budget increases for fire departments if they see firemen lolling about the firehouse. So cities have created new, highly visible jobs for their firemen. The Wall Street Journal reported recently, “In Los Angeles, Chicago and Miami, for example, 90% of the emergency calls to firehouses are to accompany ambulances to the scene of auto accidents and other medical emergencies. Elsewhere, to keep their employees busy, fire departments have expanded into neighborhood beautification, gang intervention, substitute-teaching and other downtime pursuits.” In the Illinois township where I live, the fire department drives its trucks to accompany all medical emergency vehicles, then directs traffic around the ambulance—a task which, however valuable, seemingly does not require a hook-and-ladder.

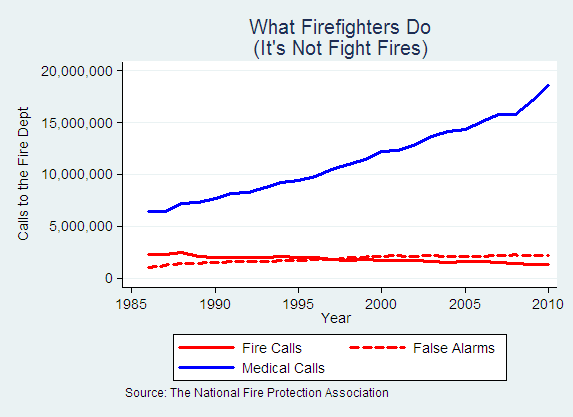

Here’s some data. Note that medical calls dwarf fire calls. Twenty five years ago false alarms were half the number of fires, today false alarms significantly exceed the number of fires.

According to Nightline it costs $3,500 every time a fire truck pulls out of a fire station in Washington, DC (25 calls in a 24 hour shift is not uncommon so this adds up quickly). Moreover, most of the time the call is not for a fire but for a minor medical problem. In many cities, both fire trucks and ambulances respond to the same calls. The paramedics do a great job but it is hard to believe that this is an efficient way to deliver medical care and transportation. A few locales have experimented with more rational systems. For example:

For calls that are not a life or death, Eastside Fire and Rescue stations [in WA state] will no longer send out a fire truck but instead an SUV with one certified medic firefighter.

Sounds obvious, but it’s hard to negotiate with heroes especially when they are unionized with strong featherbedding contracts.

Aaron Carroll on Medicaid Wars

Enough people have linked to this piece that I thought I should write a response, which you will find under the fold…

To start with a general remark. Often defenders of ACA request some kind of conservative engagement with the policy, rather than voting for the 34th (?) time for outright repeal with no coherent story of replacement. I’ve laid out a coherent scenario of how ACA could evolve into something which I consider better, and actually with only modest changes to the law itself. The mandate gets narrowed, the system as a whole evolves into means-tested vouchers (which proponents such as Zeke Emanuel favor), and possibly HSAs are given a larger role again. I say states will try to limit Medicaid growth, not that they should but that probably they can over the longer run. Defenders of the current ACA don’t have to favor my analysis, but in fact what I get back is sheer annoyance from Carroll, repetition of Carroll from various others, and an attack from Krugman, with no substantive engagement on the policy proposal at all.

Carroll writes five times that he is annoyed by my piece, but in hardly any of those cases is he disagreeing with any position I took. Let’s go through them one-by-one:

I get a bit annoyed when people claim that we can’t “afford” more government intervention or, god-forbid, single-payer. That kind of statement willfully ignores the fact that every country that has MORE government intervention spends LESS.

I most definitely did not say this and in fact I mentioned that single payer systems lower cost. Spending more on Medicaid, however, will not save the U.S. money (the Oregon study shows this), whether or not we can normatively “afford” it.

I get a bit annoyed by the claim that an expansion of government insurance leads to lines and waiting when lots of countries have universal access and less of a wait-time problem than we do.

A significant influx of people into Medicaid, under current institutions, will lead to more queuing. That is true whether or not you think other countries with single-payer have big queueing problems. What I wrote was this:

Unfortunately, Medicaid has some of the worst features of single-payer systems. Typically, a single-payer system will bargain down medical prices, thus adding to affordability, but at the risk of having long lines of patients waiting for care. As it stands now, though, the low reimbursement rates of Medicaid already lead to long lines, or an inability to find a good doctor altogether, while the higher reimbursement rates of Medicare and private insurance keep health care costs high.

It’s even carefully worded “…at the risk of having long lines of patients waiting for care.” Supply elasticities are positive and so single-payer systems do run this risk. Yet I am clear that in critical regards the systems of other countries get the better end of this deal compared to the United States.

Another bit:

I get a bit annoyed by blanket claims that doctors won’t accept Medicaid. Such statements often ignore the fact that the majority of Medicaid beneficiaries are children and pregnant women. We don’t need all types of doctors to accept Medicaid patients in equal numbers. They also ignore the fact that lots of doctors won’t accept new patients with Medicare or private insurance, either.

It is very difficult to find a good doctor in northern Virginia who takes Medicaid and I speak from personal experience (helping others). Or try any number of basic websites, with common quotations such as “Finding a Medicaid doctor constitutes a challenge…” Medicaid dentists are hard to find. Try calling say the Washingtonian “best doctors” list and see how many of them take Medicaid. Large numbers of doctors do take Medicaid but overall they tend to be much worse and there are also problems with queuing. Think about it: why would the lower payers end up first in line?

There is more annoyance:

I get a bit annoyed when people just claim government programs are “unpopular”. Like Medicare? I don’t think so. Is there any evidence that Medicaid is unpopular? I’d like to see it. Personally, I think that the fact that (a) all 50 states have bought in over time and (b) the Supreme Court just ruled that threatening to take it away is “coercive” speaks to the opposite. Additionally, polling shows the opposite of what Tyler (and lots of others) suggest.

I am sorry but this is a total “read fail.” I am saying Medicaid (not “government programs” or “Medicare”) will become increasingly unpopular. (In fact I am known for arguing that big government as a whole is quite popular.) Every day in the newspaper there is handwringing by governors, not all Republican ones, about wishing to limit or escape Medicaid obligations. A lot of them would prefer to get block grants and spend the money elsewhere (a simple question for Carroll: if Medicaid is so popular with voters, there is no reason to fear block grants to the states, right? Voters surely will insist that Medicaid spending be kept at current levels or perhaps even increased.) Daily Kos serves up plenty of evidence for the lukewarm support for Medicaid, as does Ezra Klein: “But, for a host of reasons, Democrats worry that Medicaid is more endangered than people realize.” Also note how skimpy Medicaid coverage is in many states. A lot of states don’t really try to cover poor adults, without children, at all. Frankly this is standard fare, especially on the left, but somehow if I write it he gets annoyed.

If you poll people and ask them whether they favor health care for the poor, of course they will say yes. The bottom line is this: right now we are borrowing about forty cents of every dollar spent. As we move toward fiscal balance, which are among the most vulnerable programs? Defense spending may be cut somewhat, but Medicaid is far more vulnerable than either Social Security or Medicare. I didn’t know that was under dispute and in fact it really isn’t.

Some more annoyance from Carroll:

I get a bit annoyed at the blanket acceptance of the awesomeness of the free market in health care, when there is no phenomenal evidence of its success. And again, those countries with less free market are cheaper, universal, and often just as good. So why are we always trying to run away from them?

That is another “read fail.” What did I call for in the column?

We would then have government-subsidized and mandated catastrophic insurance, and a freer market for other health care expenditures. We might even return to a health savings account approach on the noncatastrophic side.

I also note in the column that is not my first best, but we Americans probably cannot get easily to a first best system (for me a Singapore-style system, with single payer on the catastrophic side rather than mandates for private insurance purchase). My accompanying blog post even noted that the HSAs could be supplemented with government funds, if it was so desired.

The real argument of the column is that ACA will fall apart for political reasons because it creates too many different groups with different treatment. The “mood affiliation” of the column is something other than celebration of ACA, and so Carroll pulls out all of the old chestnuts and attacks them, rather than responding to the actual argument. Basically he should go back and reread the piece itself.

The new tug of war over Medicaid

My New York Times column is here, it has two parts, a prediction and a proposal. The prediction:

Medicaid has never been especially popular, and when its expanded role becomes more widely understood, it is likely to become less popular still.

I am not expecting that governors will turn away nearly-free federal dollars outright. (Though probably some will, here is an update on how the governors are reacting, which as I see it involves lots of bargaining.) I am predicting that the extreme subsidies for states to hop on to the expansion will at some point weaken or go away.

Change might come soon. If Mitt Romney wins the presidential election, and if Republicans control both houses of Congress, they could turn Medicaid into a block grant program, where states can spend the money as they wish.

Even if President Obama is re-elected, some state governments will work hard to reduce the number of people covered by Medicaid. State officials know that limiting Medicaid will place more individuals in the new, subsidized health care exchanges, and that those bills will be paid by the federal government. The basic dynamic is that state and federal governments have opposite incentives as to how many people should be kept in Medicaid.

The proposal? Here is my best take on how Obamacare might evolve into something more practical:

1. Many of the states slip out of expanded Medicaid obligations and many employers slip out of expanded mandate obligations to cover their employees (waivers, willingness to pay fines, lobby to have the law altered). The system evolves toward a form of means-tested vouchers, sold on the exchanges.

2. The subsidies for the private exchanges become so expensive that the individual mandate is limited in scope. Eventually the mandate applies to catastrophic coverage only.

3. For catastrophic coverage, we move toward a mandate and subsidized exchanges, and for non-catastrophic coverage there is no mandate and health savings accounts, the latter supplemented by public contributions if needed or if you wish.

I am not predicting that, nor is it my first or even preferred second-best solution. It is however the best solution I can see evolving out of ACA in its current form.

Medicaid Wars, Episode IV

While the resistance of Republican governors has dominated the debate over the health-care law in the wake of last month’s Supreme Court decision to uphold it, a number of Democratic governors are also quietly voicing concerns about a key provision to expand coverage.

At least seven Democratic governors have been noncommittal about their willingness to go along with expanding their Medicaid programs, the chief means by which the law would extend coverage to millions of Americans with incomes below or near the poverty line.

Here is more.