Category: Medicine

Intergenerational transmission of mental health problems

We estimate health associations across generations and dynasties using information on healthcare visits from administrative data for the entire Norwegian population. A parental mental health diagnosis is associated with a 9.3 percentage point (40%) higher probability of a mental health diagnosis of their adolescent child. Intensive margin physical and mental health associations are similar, and dynastic estimates account for about 40% of the intergenerational persistence. We also show that a policy targeting additional health resources for the young children of adults diagnosed with mental health conditions reduced the parent-child mental health association by about 40%.

That is from a new NBER working paper from Aline Bütikofer, Krzysztof Karbownik, and Fanny Landaud.

China estimate of the day

The paper’s title is “The Largest Insurance Expansion in History: Saving One Million Lives Per Year in China”:

The New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) rolled out in China from 2003-2008 provided insurance to 800 million rural Chinese. We combine aggregate mortality data with individual survey data, and identify the impact of the NCMS from program rollout and heterogeneity across areas in their rural share. We find that there was a significant decline in aggregate mortality, with the program saving more than one million lives per year at its peak, and explaining 78% of the entire increase in life expectancy in China over this period. We confirm these mortality effects using micro-data on mortality, other health outcomes, and utilization.

It is striking how few Westerns have even heard of this policy, one of the more important global events in recent years. I do however wish to ask if this estimate is in accord with other, more general estimates from the literature. The Amish, for instance, don’t see doctors so often and their life expectancy seems to be perfectly fine. The new paper is from Jonathan Gruber, Mengyun Li, and Junjian Yi.

The Birth-Weight Pollution Paradox

Maxim Massenkoff asks a very good question. If pollution reduces birth weight as much as the micro studies on pollution suggest, why aren’t birth weights very low in very polluted cities and countries? Figure 1, for example, shows birth weights in a variety of highly polluted world cities. The yellow dashed and blue lines show “predicted” birth weights extrapolated from the well-known Alexander and Schwandt “Volkswagen study” which looked at the effects of increased pollution in the United States. Despite the fact that every one of the highly-polluted cities is much more polluted than the most polluted US city, birth weight is not tremendously lower in these cities. Indeed, there is no obvious correlation between birth weight and pollution at all.

Similarly, US cities were more polluted in the past but were birth weights lower in the past? Figure 2 shows a number of US cities which were two to three times more polluted in 1972 (right side of diagram) than 2002 (left side of diagram). Yet, birth weights do not appear lower in the more polluted past and certainly do not follow the extrapolated birth weight-pollution predictions from the micro literature.

Similarly, US cities were more polluted in the past but were birth weights lower in the past? Figure 2 shows a number of US cities which were two to three times more polluted in 1972 (right side of diagram) than 2002 (left side of diagram). Yet, birth weights do not appear lower in the more polluted past and certainly do not follow the extrapolated birth weight-pollution predictions from the micro literature.

Massenkoff looks at a variety of possible explanations. One possibility, for example, is culling. Perhaps in highly polluted areas there are more miscarriages, still births or difficulty conceiving with the result that the observed sample of births is highly selected. There is some evidence that pollution increases miscarriages and stillbirths but these tend to be correlated with lower birth weight–a scarring effect rather than a culling effect. In addition, the effect of pollution on miscarriages and stillbirths also appears to be bigger on a micro level than on a macro level. That is, these rates aren’t massively higher in high pollution countries.

Another possibility is that pollution isn’t that bad and, in particular, not as bad as I have suggested. As a good Bayesian, I update, but for reasons I have given here, it’s not justifiable to update very much.

I assume, as I always do, that there are some overestimates in the micro literature for the usual reasons. But, more fundamentally, my best guess for the birth-weight pollution paradox is that weight is one of the easiest margins on which the body can adapt and compensate. Even in poor countries there are plenty of calories to go around and so it’s relatively easy for the body to adjust to higher pollution, on this margin. Indeed, weight is known as a variable that creates paradoxes!

Micro studies on weight and exercise, for example, show that exercise reduces weight. But looking across countries, societies, and time we don’t see big effects–indeed, calorie expenditure doesn’t vary much with exercise! Importantly, notice that the micro-estimates are correct. If you increase physical activity for the next 3 months, holding all else equal (which is possible for 3 months), you will lose weight. However, the micro estimates are difficult to extrapolate to permanent, long-run changes because there are complex, adaptive mechanisms governing weight, calorie consumption and energy expenditure.

The exercise paradox doesn’t mean that exercise isn’t good for you–the evidence on the benefits of exercise is extensive and credible. In the same way the birth-weight pollution paradox doesn’t mean that pollution isn’t harmful–the evidence on the costs of pollution is extensive and credible. In particular, it’s going to be much harder to adapt to pollution for heart disease, cancer, life expectancy and IQ than for weight.

I am always impressed with papers that present big, obviously-true facts that most people have simply missed. Massenkoff is becoming a leader in this field.

Is “Lab Leak” now proven?

The WSJ ran a widely discussed article a few days ago, and many people have concluded that the Lab Leak hypothesis is now confirmed. I’ve now read the piece, and I don’t see relevant new information in there. The New York Times ran a rebuttal of sorts, with this as one key paragraph:

Recent news reports have unearthed new information about researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology who became sick in 2019. The news reports suggested that one of them could be patient zero. The information about the sick workers was first discovered at the end of the Trump administration. By August 2022, however, intelligence analysts had dismissed the evidence, saying it was not relevant. Intelligence officials determined that the sick workers could not tell them anything about whether a lab leak or natural transmission was more likely. Intelligence agencies view the information about the cases neutrally, arguing that they do not buttress the case for the lab leak or for natural transmission, according to officials briefed on the intelligence.

I read the London Times report, and didn’t see fundamentally new information in there either.

To be clear, I think the chance of Lab Leak being true is reasonably high, due to the accumulation of a lot of circumstantial evidence. But I don’t think the new accounts are anything close to a slam-dunk, nor do they show that any of the researchers were “Patient Zero.” That may well change as further information comes out, but so far it is a mistake to conclude that Lab Leak has been demonstrated to be true.

Addendum: As a side note, I am a little worried by how many people seem to be happy that Lab Leak hypothesis is (supposedly) confirmed. I suppose it would mean you could feel vindicated in a certain kind of contempt for elites, both American and Chinese. But under most normal views, the world where Lab Leak is true is a worse world than the world where Lab Leak is false. So you should instead feel sad and upset if you think it is true, rather than happy or gleeful. If you feel vindicated, it is a sign of a partial cognitive and emotive defect.

Second Addendum: This new national intelligence report doesn’t seem to confirm the Lab Leak take (though it doesn’t refute it either). It pretty definitely downplays the import of the scientists getting sick. Again, it is fine to not trust this report, but still a likely mistake to think new information has been coming out. Here is a good WaPo look at where things stand. Here are comments from Scott Sumner.

Does Britain Have High or Low State Capacity?

Tim Harford writing at the FT covers the question “Is it even possible to prepare for a pandemic?” drawing on my paper with Tucker Omberg.

[I]n an unsettling study published late last year, the economists Robert Tucker Omberg and Alex Tabarrok took a more sophisticated look at this question and found that “almost no form of pandemic preparedness helped to ameliorate or shorten the pandemic”. This was true whether one looked at indicators of medical preparedness, or softer cultural factors such as levels of individualism or trust. Some countries responded much more effectively than others, of course — but there was no foretelling which ones would rise to the challenge by looking at indicators published in 2019. One response to this counter-intuitive finding is that the GHS Index doesn’t do a good job of measuring preparedness. Yet it seemed plausible at the time and it still looks reasonable now.

…perhaps we need to take the Omberg/Tabarrok study seriously: maybe conventional preparations really won’t help much. What follows? One conclusion is that we should prepare, but in a different way….Preparing a nimble system of testing and of compensating self-isolating people would not have figured in many 2019 pandemic plans. It will now. Another form of preparation which might yet pay off is sewage monitoring, which can cost-effectively spot the resurgence of old pathogens and the appearance of new ones, and may give enough warning to stop some future pandemics before they start. And, says Tabarrok, “Vaccines, vaccines, vaccines”. The faster our systems for making, testing and producing vaccines, the better our chances; all these things can be prepared.

One thing that did seem to matter, as Tim notes, was state capacity. In other words, it’s not so much being prepared as being prepared to act. And here I have a mild disagreement with Tim. He writes:

In an ill-prepared world, the UK is often thought to have been more ill-prepared than most, perhaps because of the strains caused by austerity and the distractions of the Brexit process.

My view is that the UK got three very important things right. The UK was the first stringent authority to approve a COVID vaccine. The UK switched to first doses first and the UK produced and ran the most important therapeutics trial, the Recovery trial. Each of these decisions and programs saved the lives of tens of thousands of Britons. The Recovery trial may have saved millions of lives worldwide.

I don’t claim that Britain did everything right, or that they did all that they could have done, but these three decisions were important, bold and correct. The coexistence of both high and low state capacity within the same nation can be surprising. The United States, for example, achieved an impressive feat with Operation Warp Speed, yet simultaneously, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) flailed and failed. Likewise, India maintains a commendable space program and an efficient electoral system, even while struggling with tasks that seem comparatively simpler, like issuing driver’s licenses.

Instead of painting countries with a broad brush of ‘high’ or ‘low’ state capacity, we should recognize multi-dimensionality and divergence. How do political will, resources, institutional robustness, culture, and history explain capacity divergence? If we understood the reasons for capacity divergence we might be able to improve state capacity more generally. Or we might better be able to assign tasks to state or market with perhaps very different assignments depending on the country.

Vaccination sentences to ponder

None of the incidences of myopericarditis pooled in the current study were higher than those after smallpox vaccinations and non-COVID-19 vaccinations, and all of them were significantly lower than those in adolescents aged 12–17 years after COVID-19 infection.

I would gladly see a refereed symposium on attempts to overturn this result. Individuals with rejected papers could publish those rejected works on a separate website, with the accompanying referee reports of course. One side will try to tell you that “the elites” are against debate. It is sooner the case that the level of rigor in a useful debate should correspond to the level of rigor a subject matter requires.

Via Megan McArdle.

UK NHS fact of the day

Germany has six for every thousand people, Belgium has five, we have two.

Here is an essay by Sam Freedman, “How Bad Does It Need to Get?”, via Nick Thornsby.

Free Formatting For All on First Submission!

Many years ago I was incredulous when my wife told me she had to format a paper to meet a journal’s guidelines before it was accepted! Who could favor such a dumb policy? In economics, the rule is you make your paper look good but you don’t have to fulfill all the journal’s guidelines until after the paper is accepted. Sensible!

A paper just published in BMC Medicine estimates that this obtrusive norm costs researchers in biomedical journals alone some $230 million a year in wasted time. That’s consistent with an earlier study which estimated that over a billion dollars worth of time was wasted reformatting papers in all scientific fields. Quoting from that earlier study:

Our data show that nearly 91% of authors spend greater than four hours and 65% spend over eight hours on reformatting adjustments before publication…Among the time-consuming processes involved are adjusting manuscript structure (e.g. altering abstract formats), changing figure formats, and complying with word counts that vary significantly depending on the journal. Beyond revising the manuscript itself, authors often have to adjust to specific journal and publisher online requirements (such as re-inputting data for all authors’ email, office addresses, and disclosures). Most authors reported spending “a great deal” of time on this reformatting task. Reformatting for these types of requirements reportedly caused three month or more delay in the publication of nearly one fifth of articles and one to three month delays for over a third of articles.

It’s all very depressing. If we can’t get rid of unproductive paper reformatting standards–which benefit no one–how can we expect to tackle monumental tasks that require navigating complex tradeoffs such as resolving global climate change or making the tax code more just and efficient?

Yet perhaps there is hope. The BMC Medicine paper was covered in Nature and the authors have started a petition to change the reformatting norm. Do your part. Sign the petition! Free formatting for all on first submission!

Emergent Ventures winners, 26th cohort

Winston Iskandar, 16, Manhattan Beach, CA, an app for children’s literacy and general career development. Winston also has had his piano debut at Carnegie Hall.

ComplyAI, Dheekshita Kumar and Neha Gaonkar, Chicago and NYC, to build an AI service to speed the process of permit application at local and state governments.

Avi Schiffman and InternetActivism, “leading the digital front of humanitarianism.” Avi is a repeat winner.

Jarett Cameron Dewbury, Ontario, and Cambridge MA, General career support, AI and biomedicine, including for the study of environmental enteric dysfunction. Here is his Twitter.

Ian Cheshire, Wallingford, Pennsylvania, high school sophomore, general career support, tech, start-ups, and also income-sharing agreements.

Beyzamur Arican Dinc, psychology Ph.D student at UCSB, regulation of emotional dyads in relationships and marriages, from Istanbul.

Ariana Pineda, Evanston, Illinois, Northwestern. To attend a biology conference in Prospera, Honduras.

Satvik Agnihotri, high school, NYC area, to visit the Bay Area for a summer, study logistics, and general career development.

Michael Loftus, Ann Arbor, for a neuro tech hacker house, connected to Myelin Group.

Keir Bradwell, Cambridge, UK, Political Thought and Intellectual History Masters student, to visit the U.S. to study Mancur Olson and Judith Shklar, and also to visit GMU.

Vaneeza Moosa, Ontario, incoming at University of Calgary, “Developing new therapies for malignant pleural mesothelioma using epigenetic regulators to enhance tumor growth and anti-tumor immunity with radiation therapy.”

Ashley Mehra, Yale Law School, background in classics, general career development and for eventual start-up plans.

An important project not yet ready to be announced, United Kingdom.

Jennifer Tsai, Waterloo, Ontario and Geneva (temporarily), molecular and computational neuroscience, to study in Gregoire Courtine’s lab.

Asher Parker Sartori, Belmont, Massachusetts, working with Nina Khera (previous EV winner), summer meet-up/conference for young bio people in Hanover, New Hampshire.

Nima Pourjafar, 17, starting this fall at Waterloo, Ontario. For general career development, interested in apps, programming, economics, solutions to social problems.

Karina, 17, sophomore in high school, neuroscience, optics, and light, Bellevue, Washington.

Sana Raisfirooz, Ontario, to study bioelectronics at Berkeley.

James Hill-Khurana (left off an earlier 2022 list by mistake), Waterloo, Ontario, “A new development environment for digital (chip) design, and accompanying machine learning models.”

Ukraine winners

Tetiana Shafran, Kyiv, piano, try this video or here are more. I was very impressed.

Volodymyr Lapin, London, Ukraine, general career development in venture capital for Ukraine.

Air Pollution Redux

New York City today has the worst air quality in the world, so now seems like a good time for a quick redux on air pollution. Essentially, everything we have learned in the last couple of decades points to the conclusion that air pollution is worse than we thought. Air pollution increases cancer and heart disease and those are just the more obvious effects. We now also now know that it reduces IQ and impedes physical and cognitive performance on a wide variety of tasks. Air pollution is especially bad for infants, who may have life-long impacts as well as the young and the elderly. I’m not especially worried about the wildfires but the orange skies ought to make the costs of pollution more salient. As Tyler noted, one reason air pollution doesn’t get the attention that it deserves is that it’s invisible and the costs are cumulative:

Air pollution causes many deaths. But it is rare to see or read about a person dying directly from air pollution. Lung cancer and cardiac disease are frequently cited as causes of death, even though they may stem from air pollution.

That’s the bad news. The good news, hidden inside the bad news, is that the costs of air pollution on productivity are so high that there are plausible ways of reducing some air pollution and increasing health and wealth, especially in high pollution countries but likely also in the United States with well-targeted policies.

For evidence on the above, you can see some of the posts below. Tyler and I have been posting about air pollution for a long time. Tyler first said air pollution was an underrated problem in 2005 and it was still underrated in 2021!

- Why the New Pollution Literature is Credible

- Air Pollution Reduces IQ, A Lot

- Air Pollution Kills

- David Wallace-Wells with a good overview.

- A good overview of the non-health impacts of pollution.

The Poop Detective

Wastewater surveillance is one of the few tools that we can use to prepare for a pandemic and I am pleased that it is expanding rapidly in the US and around the world. Every major sewage plant in the world should be doing wasterwater surveillance and presenting the results to the world on a dashboard.

I was surprised to learn that wastewater surveillance is now so good it can potentially lock-on to viral RNA from a single infected individual. An individual with an infection from a common SARS-COV-2 lineage like omicron won’t jump out of the data but there are rare, “cryptic lineages” which may be unique to a single individual.

Marc Johnson, a virologist at the University of Missouri and one of the authors of a recent paper on cryptic lineages in wastewater, believes he has evidence for a single infected individual who likely lives in Columbus, Ohio but works in the nearby town, Washington Court House. In other words, they poop mostly at home but sometimes at work.

Twitter: First, the signal is almost always present in the Columbus Southerly sewershed, but not always at Washington Court House. I assume this means the person lives in Columbus and travels to WCH, presumably for work. Second, the signal is increasing with time. Washington Court House had its highest SARS-CoV-2 wastewater levels ever in May, and the most recent sequencing indicates that this is entirely the cryptic lineage.

Moreover the person is likely quite sick:

Third, I’ve tried to calculate how much viral material this person is shedding. (Multiply the cryptic concentration by the total volume). I’ve done this several times and gotten pretty consistent results. They are shedding a few trillion (10^12) genomes/day. What does this tell us? How much tissue is infected? It’s impossible to know for sure. Chronically infected cells probably don’t release much, but acutely infected cells produce a lot more. I gather a typical output in the lab is around 1,000 virus per infected cell. If we assume we are getting 1,000 viral particles per infected cell, that would mean there are at least a billion infected cells. The density of monolayer epithelial cells is around 300k cells/sq cm. A billion cells would represent around 3.5 square feet of epithelial tissue! Don’t get me wrong. The intestines have a huge surface are and 3 square feet is a tiny fraction of the total. But it’s still a massive infection, no matter how you slice it….My point is that this patient is not well, even if they don’t know it, but they could probably be helped if they were identified.

…If you are the individual, let me know. There is a lab in the US that can do ‘official’ tests for COVID in stool, and there are doctors that I can put you in contact with that would like to try to help you.

So if you poop in Columbus Ohio and occasionally in Washington Court House and have been having some GI issues contact Marc!

Hat tip to Marc for using the twitter handle @SolidEvidence.

The Growing Market for Cancer Drugs

In my TED talk on growth and globalization I said:

If China and India were as rich as the United States is today, the market for cancer drugs would be eight times larger than it is now. Now we are not there yet, but it is happening. As other countries become richer the demand for these pharmaceuticals is going to increase tremendously. And that means an increase incentive to do research and development, which benefits everyone in the world. Larger markets increase the incentive to produce all kinds of ideas, whether it’s software, whether it’s a computer chip, whether it’s a new design.

…[T]oday, less than one-tenth of one percent of the world’s population are scientists and engineers. The United States has been an idea leader. A large fraction of those people are in the United States. But the U.S. is losing its idea leadership. And for that I am very grateful. That is a good thing. It is fortunate that we are becoming less of an idea leader because for too long the United States, and a handful of other developed countries, have shouldered the entire burden of research and development. But consider the following: if the world as a whole were as wealthy as the United States is now there would be more than five times as many scientists and engineers contributing to ideas which benefit everyone, which are shared by everyone….We all benefit when another country gets rich.

A recent piece in the FT illustrates:

AstraZeneca’s chief executive returned from a recent trip to China exuberant about an “explosion” of biotech companies in the country and the potential for his business to deliver drugs discovered there to the world….Many drugmakers are tempted by China’s large, ageing population, which is increasingly affected by chronic diseases partly caused by smoking, pollution and more westernised diets….the opportunity lies not just in Chinese patients, but also in the country’s scientists. “The innovation power has changed,” said Demaré. “It is no more ‘copy, paste’. They really have the power to innovate and put all the money in. There’s a lot of start-ups and we are a part of that.”

As I concluded my talk:

Ideas are meant to be shared, one idea can serve the world. One idea, one world, one market.

Why I am not entirely bullish on brain-computer interface

I agree that miracles may well be possible for disabled individuals, but I am less certain about their more general applicability. Here is one excerpt from my latest Bloomberg column:

Another vision for this technology is that the owners of computers will want to “rent out” the powers of human brains, much the way companies rent out space today in the cloud. Software programs are not good at some skills, such as identifying unacceptable speech or images. In this scenario, the connected brains come largely from low-wage laborers, just as both social media companies and OpenAI have used low-wage labor in Kenya to grade the quality of output or to help make content decisions.

Those investments may be good for raising the wages of those people. Many observers may object, however, that a new and more insidious class distinction will have been created — between those who have to hook up to machines to make a living, and those who do not.

Might there be scenarios where higher-wage workers wish to be hooked up to the machine? Wouldn’t it be helpful for a spy or a corporate negotiator to receive computer intelligence in real time while making decisions? Would professional sports allow such brain-computer interfaces? They might be useful in telling a baseball player when to swing and when not to.

The more I ponder these options, the more skeptical I become about large-scale uses of brain-computer interface for the non-disabled. Artificial intelligence has been progressing at an amazing pace, and it doesn’t require any intrusion into our bodies, much less our brains. There are always earplugs and some future version of Google Glass.

The main advantage of the direct brain-computer interface seems to be speed. But extreme speed is important in only a limited class of circumstances, many of them competitions and zero-sum endeavors, such as sports and games.

Nonetheless I am glad to the FDA is allowing Neuralink’s human trials to proceed — I would gladly be proven wrong.

Two Podcasts

Two podcasts I have enjoyed recently, First, The Social Radars, headed by Jessica Livingston and Carolynn Levy, co-founder and managing director of Y Combinator respectively. Jessica and Carolynn bring a lot of experience and trust with them so the entrepreneurs they interview open up about the realities of startups. Here is a great interview with David Lieb, creator of Google Photos and before that the highly successful failure, Bump.

I’ve also enjoyed the physician brothers Daniel and Mitch Belkin at The External Medicine Podcast. Here’s a superb primer on drug development from the great Derek Lowe.

Can the Shingles Vaccine Prevent Dementia?

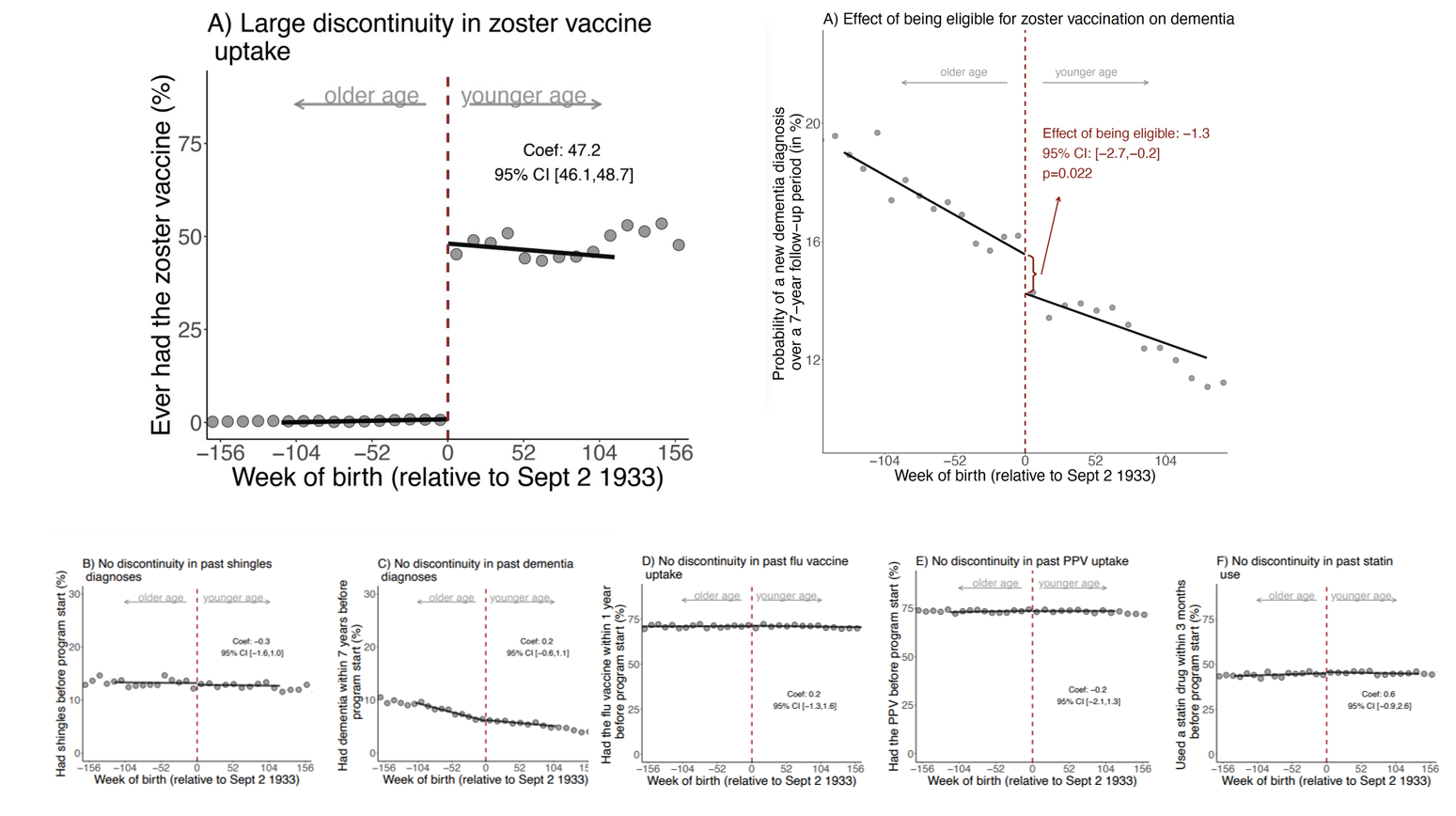

A new paper provides good evidence that the shingles vaccine can prevent dementia, which strongly suggests that some forms of dementia are caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), the virus that on initial infection causes chickenpox. The data come from Wales where the herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax) first became available on September 1 2013 and was rolled out by age. At that time, however, it was decided that the vaccine would only be available to people born on or after September 2 1933. In other words, the vaccine was not made available to 80 year olds but it was made available to 79 year and 364-day olds. (I gather the reasoning was that the benefits of the vaccine decline with age and an arbitrary cut point was chosen.)

The cutoff date for vaccine eligibility means that people born within a week of one another have very different vaccine uptakes. Indeed, the authors show that only 0.01% of patients who were just one week too old to be eligible were vaccinated compared to 47.2% among those who were just one week younger. The two groups of otherwise similar individuals who were born around September 2 1933 are then tracked for up to seven years, 2013-2020. The individuals who were just “young” enough to be vaccinated are less likely to get shingles compared to the individuals who were slightly too old to be vaccinated (as one would expect if the vaccine is doing it’s job). But, the authors also show that the individuals who were just young enough to be vaccinated are less likely to get dementia compared to the individuals who were slightly too old to be vaccinated, especially among women. A number of robustness tests finds no other sharp discontinuities in treatments or outcomes around the Sept 2, 1933 cut point.

The following graph summarizes. The top left panel shows that the cutoff led to big differences in vaccine uptake, the top right panel shows that there was a smaller but sharp decline in dementia in the vaccinated group. The bottom panel shows that was no discontinuity in a variety of other factors.

Read the whole thing.

I have had my shingles vaccine. As I have said before, vaccination is the gift of a superpower.