Category: Medicine

Humiliation, the soda tax, and deadweight loss

Catherine Rampell’s excellent column considers the case for a soda tax in Britain. Here is one bit:

Why not just target the output, rather than some random subset of inputs? We could tax obesity if we wanted to. Or if we want to seem less punitive, we could award tax credits to obese people who lose weight. A tax directly pegged to reduced obesity would certainly be a much more efficient way to achieve the stated policy goal of reducing obesity.

Of course, “fat taxes,” even when framed as weight-loss tax credits, seem pretty loathsome. Why is . . . unclear.

We tax soda instead, even though that is less effective, for instance because soda drinkers may substitute into other sugary beverages. We are unwilling to humiliate the obese by taxing them directly, and so our chosen policies do less to help…the obese. (That’s assuming that attempting to shift their consumption behavior helps them at all, which is debatable.) As Robin Hanson has told us many times, politics isn’t about policy…

Do Americans see trade as an opportunity or a threat?

Opportunity! That is from Justin Wolfers.

Why Buses and Other Things Should Be More Dangerous

Jeff Kaufman writes:

Buses are much safer than cars, by about a factor of 67 [1] but they’re not very popular. If you look at situations where people who can afford private transit take mass transit instead, speed is the main factor (ex: airplanes, subways). So we should look at ways to make buses faster so more people will ride them, even if this means making them somewhat more dangerous.

Here are some ideas, roughly in order from “we should definitely do this” to “this is crazy, but it would probably still reduce deaths overall when you take into account that more people would ride the bus”:

- Don’t require buses to stop and open their doors at railroad crossings.

- Allow the driver to start while someone is still at the front paying.

- Allow buses to drive 25mph on the shoulder of the highway in traffic jams where the main lanes are averaging below 10mph.

- Higher speed limits for buses. Lets say 15mph over.

- Leave (city) bus doors open, allow people to get on and off any time at their own risk.

Other ideas?

Excellent recognition of tradeoffs. Pharmaceuticals should also be more dangerous.

Hat tip: Slate Star Codex.

Will all of economic growth be absorbed into life extension?

That is the subject of the new JPE paper by Charles I. Jones, here is the abstract:

Some technologies save lives—new vaccines, new surgical techniques, safer highways. Others threaten lives—pollution, nuclear accidents, global warming, and the rapid global transmission of disease. How is growth theory altered when technologies involve life and death instead of just higher consumption? This paper shows that taking life into account has first-order consequences. Under standard preferences, the value of life may rise faster than consumption, leading society to value safety over consumption growth. As a result, the optimal rate of consumption growth may be substantially lower than what is feasible, in some cases falling all the way to zero.

It is a well-known stylized fact that the share of health care in gdp is generally rising…

Which is better? A society with quite patient, very long-lived individuals with a static standard of living, or a society of people who die at eighty but manage to double living standards every generation?

Which would we choose?

Addendum: Here is an earlier, “less gated” version of the paper.

Occupational Licensing Reduces Mobility

Brookings has a good memo on four ways occupational licensing reduces both income and geographic mobility. Here is point 1:

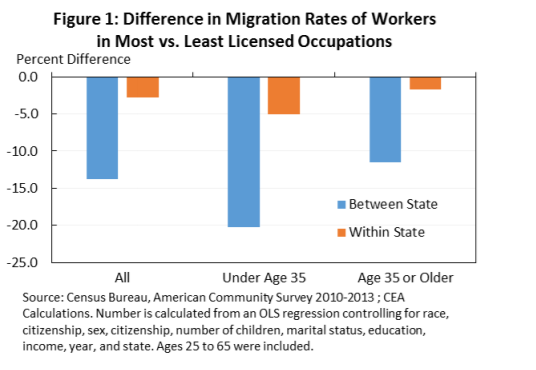

Since state licensing laws vary widely, a license earned in one state may not be honored in another. In South Carolina, only 12 percent of the workforce is licensed, versus 33 percent in Iowa. In Iowa, it takes 16 months of education to become a cosmetologist, but just half that long in New York. This licensing patchwork might explain why those working in licensed professions are much less likely to move, especially across state lines:

The graph, is from the excellent White House report on occupational licensing. The first blue column says that workers in heavily licensed occupations are nearly 15% less likely to move between states than those in less licensed occupations–this is true even after controlling for a number of other variables that might differ across occupations and also influence mobility such as citizenship, sex, number of children, and education.

The graph, is from the excellent White House report on occupational licensing. The first blue column says that workers in heavily licensed occupations are nearly 15% less likely to move between states than those in less licensed occupations–this is true even after controlling for a number of other variables that might differ across occupations and also influence mobility such as citizenship, sex, number of children, and education.

The orange column provides another test. An occupational license makes it difficult to move across states but not within a state. If workers in licensed occupations had lower rates of mobility for some other reason than the license then we would expect that workers in heavily licensed occupations would also have lower rates of within state mobility. The orange bars show that workers in heavily licensed occupations do have slightly lower rates of within state mobility but not by nearly enough to explain the dramatically lower rates of between state mobility.

Lower rates of worker mobility mean that workers are misallocated across the states in a similar way that price controls or discrimination misallocate resources and reduce total wealth. Lower rates of workforce mobility also increase the persistence of unemployment.

To its credit, the Federal government is investing in efforts to make licenses more portable including encouraging “cross-State licensing reciprocity agreements to accept each other’s licenses.” Cross-state reciprocity agreements sound like an excellent idea.

The Good News on the FDA and ANDAs

Yesterday, I pointed out that generic drug prices are falling. So what accounts for the small number of large price increases in the generic drug market? It’s a combination of market shenanigans, supply shocks, and FDA delay.

The markets where price increases have been large tend to be relatively small. Daraprim, for example, is only prescribed some 8-12 thousand times per year in the United States. The small size of these markets is no accident. Keep in mind that whatever one may think of Shkreli, he did show a kind of entrepreneurial genius in scouring the universe of drugs in the United States to select one where monopoly power could be so effectively exploited. Shkreli found a market where 1) the total size of the market was low so there wasn’t much competition but 2) the drug treated a serious illness and 3) there wasn’t a good substitute so the value of the drug to the small number of patients was very high.

In addition, Shkreli knew that he had at least a 3-4 year window of opportunity to exploit monopoly power. To compete with Daraprim a competitor would have to submit an Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) to the FDA. Despite the name, Abbreviated, it costs at least five million dollars to go through the process and right now there is a backlog of nearly 3,000 ANDAs at the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs. In recent years, it has taken 3- 4 years to get a generic drug approved. The cost is too high and the delay too long.

(I am focusing on the standard route to market entry and ignoring the possibility of importation or compounding which I discussed earlier. I’m also ignoring that Daraprim is unusual in that it was approved in 1953 before the current FDA system of safety and efficacy trials, and the FDA is being absurdly cagey about whether they would allow a simple ANDA for Daraprim. I may write about that in a future post– see here for a related case.)

So what’s the good news? In 2012 Congress passed the Generic Drug User Fee Act (GDUFA). Modeled after the very succesful PDUFA, the act earmarks fees paid by generic drug manufacturers to the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs. As a result of those fees, the FDA has hired more reviewers and they are rapidly reducing the backlog. That’s the first piece of good news.

A second piece of good news is that FDA delay isn’t the only cause of the backlog. Another cause of the ANDA backlog was an unexpected increase in the number of ANDAs. I would have been much more worried if the number of ANDAs had decreased. Despite new user fees and some increase in regulation the increase in submissions is evidence that the US generic market is competitive, vibrant, and profitable.

The generic drug market in the United States has been very successful. We are constantly told, for example, that US pharmaceutical prices are the highest in the world and that is true for patented drugs but generic drug prices in the US are among the lowest in the developed world and most prescriptions are of generics.

We can address the price hiccups in the generic market by opening up to more world suppliers, speeding up the ANDA process and keeping costs of entry low. Overall, however, we shouldn’t let the price hiccups detract attention from the fact that the generic drug market is competitive, vibrant and thriving and we want to keep it that way.

The Good News on Generic Drugs

Who could resist the story of Martin Shkreli and Turing Pharmaceuticals? Shkreli is like a villain straight from central casting; having made millions, perhaps fraudulently, as a hedge manager, he turned to pharmaceuticals where, as CEO of Turing, he bought up the marketing rights to Daraprim (pyrimethamine), a drug used by pregnant women and AIDS patients (natch), and jacked up the price from $13.50 a pill to $750 a pill. Not content with monopolizing pharmaceuticals, Shkreli also aimed to monopolize hip hop music. Shkreli on his own was a great story but add some big price increases for a handful of other generic drugs and Shrekli became an irresistible lead to a story about seemingly widespread increases in generic drug prices.

If we dig deeper, however, the big news about generic drugs is good news. Generic drug prices are falling. Three recent studies of generic drug prices all point in the same direction. Express Scripts, a large prescription drug manager, found that:

From January 2008 through December 2014, a market basket of the most commonly used generic medications decreased in price by 62.9%.

In an excellent overview the Department of Health and Human Services concluded that:

…drug acquisition costs fell for a majority of generic Medicaid prescriptions measured by both volume and total generic expenditures.

Finally the AARP studied the prices of generic drugs used by older Americans and found that:

Between January 2006 and December 2013, retail prices for 103 chronic-use generic drugs that have been on the market since the beginning of the study decreased cumulatively over 8 years by an average of 22.7 percent.

— The cumulative general inflation rate in the U.S. economy rose 18.4 percent during the same 8-year period.

Patented drugs are increasing in price so to evaluate the benefit of price decreases for generics it’s important to know that between 80 to 90 percent of all prescriptions in the United States are for generic drugs.

Tomorrow: The Good News on the FDA and ANDAs.

New Hampshire fact of the day

There are several ways of thinking about economic distress. One is inequality. Utah is the most equal state, then Alaska, Wyoming and New Hampshire. In terms of median family income, Maryland is the richest state, then New Hampshire. So the Granite State is in a sweet spot, both very rich and relatively equal. But its drug deaths exceed the national average.

That is from Scott Sumner. And this:

In contrast, the 5 states with the lowest rate of drug deaths are all in the northern plains area. (Note that the 4 most equal states and the 5 lowest drug deaths states are mostly white, but their drug death rates are vastly different.) Interestingly after the 5 plains states you have Virginia, followed by four very unequal states, with lots of poverty; Texas, New York, Mississippi and Georgia rounding out the top 10 for fewest drug deaths.

Economics isn’t everything, nor is inequality.

Does paying cash now cut your health care bill?

This one is new to me, and I cannot vouch for it. Nonetheless I wondered if this report from Melinda Beck at the WSJ might be a positive sign:

Not long ago, hospitals routinely charged uninsured patients their highest rates, far more than insured patients paid for the same services. Now, in the Alice-in-Wonderland world of health-care prices, the opposite is often true: Patients who pay up front in cash often get better deals than their insurance plans have negotiated for them.

That is partly due to new state and federal rules aimed at protecting uninsured patients from price gouging. (Under the Affordable Care Act, for example, tax-exempt hospitals can’t charge financially strapped patients much more than Medicare pays.) Many hospitals also offer discounts if patients pay in cash on the day of service, because it saves administrative work and collection hassles. Cash prices are officially aimed at the uninsured, but people with coverage aren’t legally required to use it.

Here is the full story.

The Right to Try

Here is a powerful video from the Tomorrow’s Cures Today Foundation on the right to try experimental medicines. I sometimes worry that we hold out too much promise to patients. Tomorrow’s drugs are rarely cures. Tomorrow’s drugs are a little bit better than today’s and that is how progress is made. What really matters is not the right to try per se but speeding up the process, reducing costs, and increasing investment in pharmaceutical R&D.

Nevertheless, I support the right to try. Watch the video.

Addendum: I have no direct connection to the Foundation but Bartley Madden is on the advisory board, as is Nobelist Vernon Smith, so I am delighted to promote.

Resistance to anesthesia in the 19th century

That is the topic of a new paper by Meyer R and Desai SP, here is the abstract:

News of the successful use of ether anesthesia on October 16, 1846, spread rapidly through the world. Considered one of the greatest medical discoveries, this triumph over man’s cardinal symptom, the symptom most likely to persuade patients to seek medical attention, was praised by physicians and patients alike. Incredibly, this option was not accepted by all, and opposition to the use of anesthesia persisted among some sections of society decades after its introduction. We examine the social and medical factors underlying this resistance. At least seven major objections to the newly introduced anesthetic agents were raised by physicians and patients. Complications of anesthesia, including death, were reported in the press, and many avoided anesthesia to minimize the considerable risk associated with surgery. Modesty prevented female patients from seeking unconsciousness during surgery, where many men would be present. Biblical passages stating that women would bear children in pain were used to discourage them from seeking analgesia during labor. Some medical practitioners believed that pain was beneficial to satisfactory progression of labor and recovery from surgery. Others felt that patient advocacy and participation in decision making during surgery would be lost under the influence of anesthesia. Early recreational use of nitrous oxide and ether, commercialization with patenting of Letheon, and the fighting for credit for the discovery of anesthesia suggested unprofessional behavior and smacked of quackery. Lastly, in certain geographical areas, notably Philadelphia, physicians resisted this Boston-based medical advance, citing unprofessional behavior and profit seeking. Although it appears inconceivable that such a major medical advance would face opposition, a historical examination reveals several logical grounds for the initial societal and medical skepticism.

File under “@pmarca bait.”

Hat tip goes to Neuroskeptic.

Hysteresis for legally protected ZMP elephants in Myanmar

“Unemployment is really hard to handle,” said U Saw Tha Pyae, whose six elephants have been jobless for the past two years. “There is no logging because there are no more trees.”

Myanmar’s leading elephant expert, Daw Khyne U Mar, estimates that there are now 2,500 jobless elephants, many of them here in the jungles of eastern Myanmar, about two and a half hours from the Thai border. That number would put the elephant unemployment rate at around 40 percent, compared with about 4 percent for Myanmar’s people.

“Most of these elephants don’t know what to do,” Ms. Khyne U Mar said. “The owners have a great burden. It’s expensive to keep them.”

Adult elephants, which each weigh about 10,000 pounds, eat 400 pounds of food a day and, other than circuses and logging, have limited job opportunities.

Logging is arduous. But elephant experts say hard work is one reason Myanmar’s elephants have remained relatively healthy. A 2008 study calculated that Myanmar’s logging elephants, which have a strict regimen of work and play, live twice as long as elephants kept in European zoos, a median age of 42 years compared with 19 for zoo animals.

Here is the full NYT story, via Michelle Dawson and Otis Reid. The story is interesting throughout, you will note the elephants had strong labor law protections:

The military governments adhered to a strict labor code for elephants drawn up in British colonial times: eight-hour work days and five-day weeks, retirement at 55, mandatory maternity leave, summer vacations and good medical care. There are still elephant maternity camps and retirement communities run by the government. In a country where the most basic social protections were absent during the years of dictatorship, elephant labor laws were largely respected.

Interesting throughout — I wonder what is the natural rate of unemployment for elephants in a freer labor market…?

Does Europe really have a better drinking culture for young people?

German Lopez at Vox reports:

If you look at the data, there’s no evidence to support the idea that Europe, in general, has a safer drinking culture than the US.

According to international data from the World Health Organization, European teens ages 15 to 19 tend to report greater levels of binge drinking than American teens.

This continues into adulthood. Total alcohol consumption per person is much higher in most of Europe. Drinkers in several European countries — including the UK, France, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland — are also more likely to report binge drinking than their US counterparts.

Younger teens in Europe appear to drink more, as well. David Jernigan, an alcohol policy expert at Johns Hopkins University, studied survey data, finding that 15- and 16-year-old Americans are less likely to report drinking and getting drunk in the past month than their counterparts in most European countries.

File under Wisdom of the Mormons.

“Hillary, can you excite us?”

I found the article and its photos interesting throughout. Here is commentary from Robin Hanson.

Fragments of note

…OxyContin abuse kills three times more people than gun homicides yearly.

That is from Scott Alexander, USA only, and here is Scott’s earlier post on guns, follow-up here.

Addendum: Do note the comment from GregS, this comparison may not be correct. Here is an update.