Results for “cohort” 216 found

Should economists aspire to be academics or to work in government?

From Scott Jaschik at InsideHigherEd:

The study was based on data from the National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates, and also on surveys of economics Ph.D.s who entered or left programs in certain years. The work was conducted by Wendy Stock, professor of economics at Montana State University, and John Siegfried, professor of economics at Vanderbilt University.

Comparing four cohorts of economics Ph.D.s by year graduated (from 1997 through 2011), the study found that while a majority still enter academe, that share is going down. And while salaries for those in business and industry exceeded those in academe throughout the period studied, the time span saw salaries in government grow such that they too now exceed those in academe.

In 1997 63.7% of new economics Ph.d.s went into academia, as of 2011 it is 56.3%. The government to academia salary over that same time went from 0.87 to 1.17, see the chart at the initial link. For instance:

…for those who earned Ph.D.s in 1997, the average annual salary increase was 8.2 percent. But for academics that was 5.7 percent, while for non-academics it was 15.0 percent.

You can earn more if you were hired later:

“Indeed, the median salaries of graduates of full-time permanent 9-10 month academic economists hired in 2002-3 actually exceeded the median 2003 salaries of their counterparts initially hired in 1997-98,” the paper says.

There is a marriage penalty for women but not for men, and the paper reports this:

The surveys of new Ph.D.s also asked them about the doctoral education they received. Among the findings:

- Most said that the overall emphasis in their programs was “about right.”

- Most also reported too little emphasis on “applying economic theory to real-world problems,” “understanding economic institutions and history” and “the history of economic ideas.”

- Mathematics was viewed by most as more important in graduate school than in their careers.

- Skills in application, instruction and communication were more important in their careers than in graduate school.

Here are related thoughts from Megan McArdle and from Bryan Caplan. Can any of you find a link to the actual paper on-line (try this: http://www.aeaweb.org/aea/2014conference/program/retrieve.php?pdfid=305#sthash.Avt8kMpt.dpuf)?

England fact of the day

From Sarah O’Connor and Chris Giles, this one is a bruiser:

The earnings of recent English graduates have deteriorated so rapidly since the financial crisis that the latest class is earning 12 per cent less than their pre-crash counterparts at the same stage in their careers. They also owe about 60 per cent more in student debt.

As Britain starts to emerge from the downturn, a Financial Times analysis of student loan data exposes the damage done to a generation of graduates, for whom a degree has all but ceased to be a golden ticket to a decent job. Tuition fees in England almost tripled last year to a maximum £9,000 a year.

…Each cohort of graduates since the financial crisis is earning less than the one before. New graduates who earned £15,000 or more in 2011-12 – enough to start repaying their loans – were paid on average 12 per cent less in real terms than graduates at the same stage of their careers in 2007-08.

This real terms fall is three times as deep as the decline in average pay for all full-time workers over the same period.

From the FT there is more here.

The economics of declining teacher quality

I hear this topic discussed quite often, yet rarely does this 2006 paper by Darius Lakdawalla, “The Economics of Teacher Quality,” come up in the popular conversation. Here is the abstract:

Concern is often voiced about the quality of American schoolteachers. This paper suggests that, while the relative quality of teachers is declining, this decline may be the result of technological changes that have raised the price of skilled workers outside teaching without affecting the productivity of skilled teachers. Growth in the price of skilled workers can cause schools to lower the relative quality of teachers and raise teacher quantity instead. Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth demonstrates that wage and schooling are good measures of teacher quality. Analysis of U.S. census microdata then reveals that the relative schooling and experience-adjusted relative wages of U.S. schoolteachers have fallen significantly from 1940 to 1990. Moreover, class sizes have also fallen substantially. The declines in class size and in relative quality seem correlated over time and space with growth in the relative price of skilled workers.

The jstor link is here, this version is (I think) ungated for you. Here is an ungated, earlier version with some related results. Here is a good sentence from the middle of the paper:

Both schooling and experience-adjusted wages entered a period of relative decline for teachers beginning with the cohorts entering the labor force during the 1950s.

On pp.318-318 Lakdawalla discusses the importance of superior labor market opportunities for women for the argument. Here is Lakdalla’s earlier argument that Medicare benefits the poor to a disproportionate degree.

I was reminded of the education paper by a tweet from Austan Goolsbee.

The Man of System

One sometimes hears arguments for busing or against private schools that say we need to prevent the best kids from leaving in order to benefit their less advantaged peers. I find such arguments distasteful. People should not be treated as means. I must confess, therefore, that I took some pleasure at the findings of a recent paper by Carrell, Sacerdote, and West:

We take cohorts of entering freshmen at the United States Air Force Academy and assign half

to peer groups designed to maximize the academic performance of the lowest ability students.

Our assignment algorithm uses nonlinear peer eff ects estimates from the historical pre-treatment

data, in which students were randomly assigned to peer groups. We find a negative and signi ficant treatment eff ect for the students we intended to help. We provide evidence that within our

“optimally” designed peer groups, students avoided the peers with whom we intended them to

interact and instead formed more homogeneous sub-groups. These results illustrate how policies

that manipulate peer groups for a desired social outcome can be confounded by changes in the

endogenous patterns of social interactions within the group.

I was reminded of Adam Smith’s discussion of exactly this issue in The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

The man of system, on the contrary, is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it. He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder.

Do note that this discussion is not a critique of the paper which is very well done.

The Flynn effect vs. population aging

Here is some good news for you all on Easter Sunday, good news until 2042 that is:

Although lifespan changes in cognitive performance and Flynn effects have both been well documented, there has been little scientific focus to date on the net effect of these forces on cognition at the population level. Two major questions moving beyond this finding guided this study: (1) Does the Flynn effect indeed continue in the 2000s for older adults in a UK dataset (considering immediate recall, delayed recall, and verbal fluency)? (2) What are the net effects of population aging and cohort replacement on average cognitive level in the population for the abilities under consideration?

First, in line with the Flynn effect, we demonstrated continued cognitive improvements among successive cohorts of older adults. Second, projections based on different scenarios for cognitive cohort changes as well as demographic trends show that if the Flynn effect observed in recent years continues, it would offset the corresponding age-related cognitive decline for the cognitive abilities studied. In fact, if observed cohort effects should continue, our projections show improvements in cognitive functioning on a population level until 2042—in spite of population aging.

That is from Vegard Skirbekk, Marcin Stonawski, Eric Bonsang, and Ursula M. Staudinger, and one gated link is here. Do any of you know of an ungated copy?

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Overall health inequality seems to be down

The haves are those who enjoy great health into their 90s. The have-nots are those who suffer from serious health problems and do not live to see adulthood. As we pointed out in a recent study, among those Americans who were born in 1975, the unluckiest 1 percent died in infancy, while the luckiest 1 percent can expect to live to age 105 or longer. Now let’s fast forward to those born in 2012. The bottom percentile of this cohort can expect to survive until age 18. At the other end of the spectrum, the luckiest 1 percent can expect to live to age 108. That’s a much bigger gain in life expectancy among the have-nots than among the haves. Of course, life expectancy is but one measure of health and well-being, but understanding these trends offers a more complete picture than considering income alone.

These findings run counter to headlines noting a widening gap in health outcomes between different demographic groups. For example, a study led by Jay Olshansky of the University of Illinois at Chicago recently demonstrated that the gap in life expectancy between less educated and more educated Americans has widened considerably.

While studies like these are valuable in highlighting disparities between socio-economic groups, they do not tell us much about overall health inequality. That’s because most health inequality occurs within groups. In other words, if we look at a particular demographic group, the best outcomes for people in that group are dramatically different from the worst outcomes for people in the same group. These differences overwhelm any differences in average life expectancy across demographic groups. Thus, while inequality across some demographic groups has increased, it has fallen over the entire population. Overall, therefore, the health have-nots have made progress in catching up to the health haves.

That is from Benjamin Ho and Sita Nataraj Slavov. I am open to counters on the data side, but so far this seems both a) true and b) rooftop-worthy. I am reminded of Arnold Kling’s three axes of ideology; perhaps health care inequality attracts attention only when the victims are a group (the poor) who are part of some other narrative of oppression.

Is bipolar disorder more common in highly intelligent people?

Here is a new piece by Gale CR, Batty GD, McIntosh AM, Porteous DJ, Deary IJ, and Rasmussen F.:

Abstract

Anecdotal and biographical reports have long suggested that bipolar disorder is more common in people with exceptional cognitive or creative ability. Epidemiological evidence for such a link is sparse. We investigated the relationship between intelligence and subsequent risk of hospitalisation for bipolar disorder in a prospective cohort study of 1 049 607 Swedish men. Intelligence was measured on conscription for military service at a mean age of 18.3 years and data on psychiatric hospital admissions over a mean follow-up period of 22.6 years was obtained from national records. Risk of hospitalisation with any form of bipolar disorder fell in a stepwise manner as intelligence increased (P for linear trend <0.0001). However, when we restricted analyses to men with no psychiatric comorbidity, there was a ‘reversed-J’ shaped association: men with the lowest intelligence had the greatest risk of being admitted with pure bipolar disorder, but risk was also elevated among men with the highest intelligence (P for quadratic trend=0.03), primarily in those with the highest verbal (P for quadratic trend=0.009) or technical ability (P for quadratic trend <0.0001). At least in men, high intelligence may indeed be a risk factor for bipolar disorder, but only in the minority of cases who have the disorder in a pure form with no psychiatric comorbidity.

Surely Harvard faculty would never say anything like this

SPIEGEL: How do we have to imagine this: You raise Neanderthals in a lab, ask them to solve problems and thereby study how they think?

Church: No, you would certainly have to create a cohort, so they would have some sense of identity. They could maybe even create a new neo-Neanderthal culture and become a political force.

SPIEGEL: Wouldn’t it be ethically problematic to create a Neanderthal just for the sake of scientific curiosity?

Church: Well, curiosity may be part of it, but it’s not the most important driving force. The main goal is to increase diversity. The one thing that is bad for society is low diversity. This is true for culture or evolution, for species and also for whole societies. If you become a monoculture, you are at great risk of perishing. Therefore the recreation of Neanderthals would be mainly a question of societal risk avoidance.

I find this a pretty outrageous and indefensible set of sentiments, and I am one who would like to see the United States target a higher population of 500 million through increased immigration.

It must be a misquotation. And please note that “Church” is not in fact “The Church” responding, but rather Professor George Church of Harvard University.

Here is more, with numerous hat tips to those in my Twitter feed.

What is the critical view on the lead-crime correlation?

Here is a report from Scott Firestone. He does admit that much of the evidence carries some weight, but he is less persuaded when it comes to cohort studies:

It turns out there was in fact a prospective study done—but its implications for Drum’s argument are mixed. The study was a cohort study done by researchers at the University of Cincinnati. Between 1979 and 1984, 376 infants were recruited. Their parents consented to have lead levels in their blood tested over time; this was matched with records over subsequent decades of the individuals’ arrest records, and specifically arrest for violent crime. Ultimately, some of these individuals were dropped from the study; by the end, 250 were selected for the results.

The researchers found that for each increase of 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood, there was a higher risk for being arrested for a violent crime, but a further look at the numbers shows a more mixed picture than they let on. In prenatal blood lead, this effect was not significant. If these infants were to have no additional risk over the median exposure level among all prenatal infants, the ratio would be 1.0. They found that for their cohort, the risk ratio was 1.34. However, the sample size was small enough that the confidence interval dipped as low as 0.88 (paradoxically indicating that additional 5 µg/dl during this period of development would actually be protective), and rose as high as 2.03. This is not very convincing data for the hypothesis.

For early childhood exposure, the risk is 1.30, but the sample size was higher, leading to a tighter confidence interval of 1.03-1.64. This range indicates it’s possible that the effect is as little as a 3% increase in violent crime arrests, but this is still statistically significant.

I don’t have any particular view on this matter, but if you wish can you read Drum’s response here.

Addendum: Andrew Gelman comments.

Nine Facts about Top Journals in Economics

That is the new paper by David Card and Stefano DellaVigna, here is the abstract:

How has publishing in top economics journals changed since 1970? Using a data set that combines information on all articles published in the top-5 journals from 1970 to 2012 with their Google Scholar citations, we identify nine key trends. First, annual submissions to the top-5 journals nearly doubled from 1990 to 2012. Second, the total number of articles published in these journals actually declined from 400 per year in the late 1970s to 300 per year most recently. As a result, the acceptance rate has fallen from 15% to 6%, with potential implications for the career progression of young scholars. Third, one journal, the American Economic Review, now accounts for 40% of top-5 publications, up from 25% in the 1970s. Fourth, recently published papers are on average 3 times longer than they were in the 1970s, contributing to the relative shortage of journal space. Fifth, the number of authors per paper has increased from 1.3 in 1970 to 2.3 in 2012, partly offsetting the fall in the number of articles per year. Sixth, citations for top-5 publications are high: among papers published in the late 1990s, the median number of Google Scholar citations is 200. Seventh, the ranking of journals by citations has remained relatively stable, with the notable exception of the Quarterly Journal of Economics, which climbed from fourth place to first place over the past three decades. Eighth, citation counts are significantly higher for longer papers and those written by more co-authors. Ninth, although the fraction of articles from different fields published in the top-5 has remained relatively stable, there are important cohort trends in the citations received by papers from different fields, with rising citations to more recent papers in Development and International, and declining citations to recent papers in Econometrics and Theory.

Fox and Mitchum on the Flynn Effect and how it works

James R. Flynn recommends this paper, by Fox and Mitchum, in his new book:

Secular gains in intelligence test scores have perplexed researchers since they were documented by Flynn (1984, 1987). Gains are most pronounced on abstract, so-called culture-free tests, prompting Flynn (2007) to attribute them to problem solving skills availed by scientifically advanced cultures. We propose that recent-born individuals have adopted an approach to analogy that enables them to infer higher-level relations requiring roles that are not intrinsic to the objects that constitute initial representations of items. This proposal is translated into item-specific predictions about differences between cohorts in pass rates and item-response patterns on the Raven’s Matrices, a seemingly culture-free test that registers the largest Flynn effect. Consistent with predictions, archival data reveal that individuals born around 1940 are less able to map objects at higher levels of relational abstraction than individuals born around 1990. Polytomous Rasch models verify predicted violations of measurement invariance as raw scores are found to underestimate the number of analogical rules inferred by members of the earlier cohort relative to members of the later cohort who achieve the same overall score. The work provides a plausible cognitive account of the Flynn effect, furthers understanding of the cognition of matrix reasoning, and underscores the need to consider how test-takers select item responses.

The paper is here (pdf).

Who becomes an entrepreneur?

There is a new paper by Ingrid Schoon and Kathryn Duckworth:

Taking a longitudinal perspective, we tested a developmental– contextual model of entrepreneurship in a nationally representative sample. Following the lives of 6,116 young people in the 1970 British Birth Cohort from birth to age 34, we examined the role of socioeconomic background, parental role models, academic ability, social skills, and self-concepts as well as entrepreneurial intention expressed during adolescence as predictors of entrepreneurship by age 34. Entrepreneurship was defined by employment status (being self-employed and owning a business). For both men and women, becoming an entrepreneur was associated with social skills and entrepreneurial intentions expressed at age 16. In addition, we found gender-specific pathways. For men, becoming an entrepreneur was predicted by having a self-employed father; for women, it was predicted by their parents’ socioeconomic resources. These findings point to conjoint influences of both social structure and individual agency in shaping occupational choice and implementation.

Here are Powerpoints for the paper. Here is a gated copy. For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

The culture that was Japan

“It was a generation,” Kuroda said through an interpreter, “when [baseball] coaches believed you should not drink water.”

Born in 1975, Kuroda is one of the last of a cohort of Japanese players who grew up in a culture in which staggeringly long work days and severe punishment were normal, and in which older players could haze younger ones with impunity.

Summer practices in the heat and humidity of Osaka lasted from 6 a.m. until after 9 p.m. Kuroda was hit with bats and forced to kneel barelegged on hot pavement for hours.

“Many players would faint in practice,” Kuroda said with the assistance of his interpreter, Kenji Nimura. “I did go to the river and drink. It was not the cleanest river, either. I would like to believe it was clean, but it was not a beautiful river.

“In order to play,” he added, “you had to survive. We were trained to build an immune system so that we could survive and play.”

Here is more, hat tip to Hugo. As I often say, I am a utility optimist and a revenue pessimist, for Japan most of all.

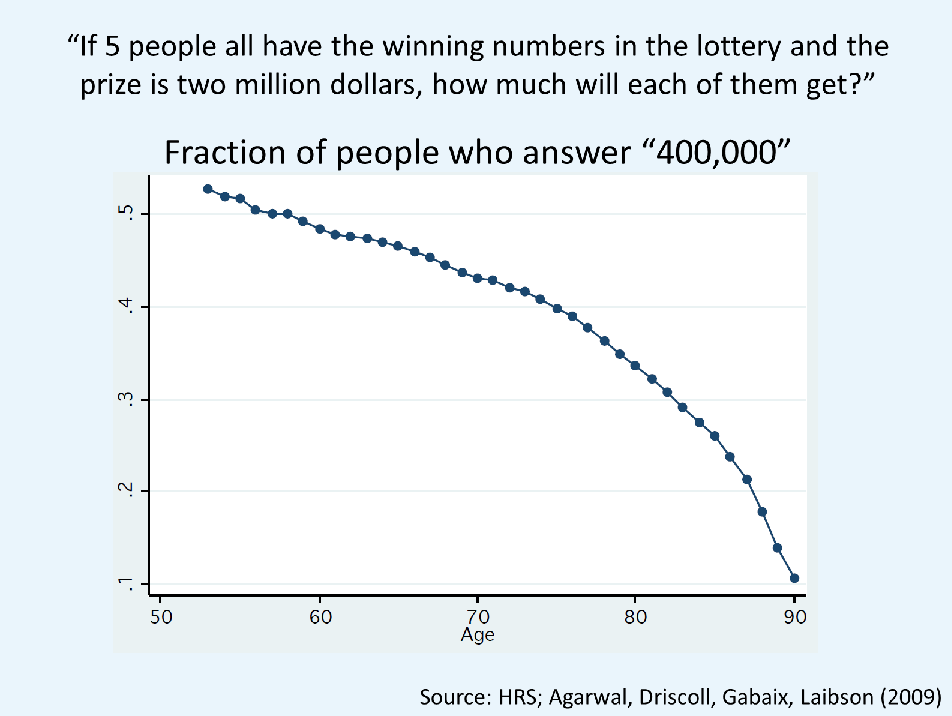

The Age of Reason

I don’t know which is scarier the height of the curve around age 50 or the slope of the curve (fyi, my guess is cohort effects are small). The slide is from David Laibson who has much more on aging and dementia; also raises issues of the value of medical care that maintains the body but not the mind.

In Praise of Private Equity

Excellent piece by Reihan Salam on private equity and how Bain fit into the larger picture of a dynamic economy.

The difficult truth that virtually no politician is prepared to acknowledge is that the road to job creation runs through job destruction.

…Chad Syverson, an economist at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, found that what separates top firms from bottom firms is, typically, a large difference in productivity, with the top ones producing almost twice as much with the same measured input. This creates an almost irresistible temptation for investors. If Firm X, languishing at the 10th percentile in terms of productivity, could somehow be overhauled to match the productivity levels achieved by Firm A, at the 90th percentile, the potential for profit would be huge. Note, however, that halving “measured input” in order to double productivity will often mean shedding the weakest performers and giving those who remain the tools they need to do their jobs better and faster. Private equity does exactly this.

What Mitt Romney discovered was that American corporations sometimes had to be dragged, wailing and whining, into a state of efficiency. As a management consultant at Bain & Company, Romney had studied successful firms and then told other firms how to replicate their strategies. But those firms had come of age in the fat years of American corporate dominance, when many believed that the Japanese could do little more than manufacture cheap toys and textiles, and many were reluctant to accept his newfangled advice. It eventually became clear that if Romney and his cohort were going to remake American business, they’d have to raise money to make their own investments. Spurred by the senior partners at Bain & Company, Romney and his merry band of consultants established Bain Capital.

I wish Romney were as eloquent in his defense as is Salam.