Results for “new service sector” 331 found

Are we undermeasuring productivity gains from the internet?, part II

From my new paper with Ben Southwood on whether the rate of progress in science is diminishing:

Similarly, the tech sector of the American economy still isn’t as big as many people think. The productivity gap has meant that measured GDP is about fifteen percent lower than it would have been under earlier rates of productivity growth. But if you look say about the tech sector in 2004, it is only about 7.7 percent of GDP (since the productivity slowdown is ongoing, picking a more recent and larger number is not actually appropriate here). A mismeasurement of that tech sector just doesn’t seem nearly large enough to fill in for the productivity gap. You might argue in response that “today the whole economy is incorporating tech,” but that doesn’t seem to work either. For one thing, recent tech incorporations typically involve goods and services that are counted in GDP. Furthermore, there is a problem of timing, namely that the U.S. productivity slowdown dates back to 1973, and that is perhaps the single biggest problem for trying to attribute this gap mainly to under-measured innovations in the tech sector.

Other research looks at “worst case” scenarios from the mismeasurement of welfare adjustments in consumer price deflators and finds a similar result: a significant effect that nonetheless does not reverse the judgement that innovation has been slowing.

The most general point of relevance here is simply that price deflator bias has been with productivity statistics since the beginning, and if anything the ability of those numbers to adjust for quality improvements may have increased with time. For instance, the research papers do not find that the mismeasurement has risen in the relevant period. You might think the introduction of the internet is still undervalued in measured GDP, but arguably the introduction of penicillin earlier in the 20th century was undervalued further yet. The market prices for those doses of penicillin probably did not reflect the value of the very large number of lives saved. So when we are comparing whether rates of progress have slowed down over time, and if we wish to salvage the performance of more recent times, we still need an argument that quality mismeasurement has increased over time. So far that case has not been made, and if you believe that the general science of statistics has made some advances, the opposite is more likely to be true, namely that mismeasurement biases are narrowing to some extent.

You will find citations and footnotes in the original. Here is my first post on whether the productivity gains from the internet are understated.

Are we undermeasuring productivity gains from the internet? part I

From my new paper with Ben Southwood on whether the rate of scientific progress is slowing down:

Third, we shouldn’t expect mismeasured GDP simply from the fact that the internet makes many goods and services cheaper. Spotify provides access to a huge range of music, and very cheaply, such that consumers can listen in a year to albums that would have cost them tens of thousands of dollars in the CD or vinyl eras. Yet this won’t lead to mismeasured GDP. For one thing, the gdp deflator already tries to capture these effects. But even if those efforts are imperfect, consider the broader economic interrelations. To the extent consumers save money on music, they have more to spend or invest elsewhere, and those alternative choices will indeed be captured by GDP. Another alternative (which does not seem to hold for music) is that the lower prices will increase the total amount of money spent on recorded music, which would mean a boost in recorded GDP for the music sector alone. Yet another alternative, more plausible, is that many artists give away their music on Spotify and YouTube to boost the demand for their live performances, and the increase in GDP shows up there. No matter how you slice the cake, cheaper goods and services should not in general lower measured GDP in a way that will generate significant mismeasurement.

Moving to the more formal studies, the Federal Reserve’s David Byrne, with Fed & IMF colleagues, finds a productivity adjustment worth only a few basis points when attempting to account for the gains from cheaper internet age and internet-enabled products. Work by Erik Brynjolfsson and Joo Hee Oh studies the allocation of time, and finds that people are valuing free Internet services at about $106 billion a year. That’s well under one percent of GDP, and it is not nearly large enough to close the measured productivity gap. A study by Nakamura, Samuels, and Soloveichik measures the value of free media on the internet, and concludes it is a small fraction of GDP, for instance 0.005% of measured nominal GDP growth between 1998 and 2012.

Economist Chad Syverson probably has done the most to deflate the idea of major unmeasured productivity gains through internet technologies. For instance, countries with much smaller tech sectors than the United States usually have had comparably sized productivity slowdowns. That suggests the problem is quite general, and not belied by unmeasured productivity gains. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the productivity slowdown is quite large in scale, compared to the size of the tech sector. Using a conservative estimate, the productivity slowdown implies a cumulative loss of $2.7 trillion in GDP since the end of 2004; in other words, output would have been that much higher had the earlier rate of productivity growth been maintained. If unmeasured gains are to make up for that difference, that would have to be very large. For instance, consumer surplus would have to be five times higher in IT-related sectors than elsewhere in the economy, which seems implausibly large.

You can find footnotes and references in the original. Here is my earlier post on the paper.

Television facts of the day

There were 496 scripted TV shows made in the US last year, more than double the 216 series released in 2010. In the past eight years the number of shows grew by 129 per cent, while the US population rose only 6 per cent. The trend is set to deepen, as groups like AT&T’s WarnerMedia commission dozens of new series to convince people to sign up for their streaming services.

…In the span of about six months, Disney, Apple, AT&T and Comcast are launching new streaming services, asking people to pay nothing for some services or up to $15 a month to watch their libraries of films and shows.

Here is more from Anna Nicolaou and Alex Barker at the FT. Yes, you might be tempted to short this sector and perhaps I am too. Still, another possible part of the equilibrium adjustment is simply that the market swallows the content and factor prices fall, a’la music streaming. That would be one way to get all of those costly special effects out of so many movies.

Robert Solow on the future of leisure

…there is no logical or physical reason that the work year of a machine should not actually increase, say. But it would seem more likely that increased leisure over the next century should be accompanied by a smaller stock of capital (per worker), smaller gross investment (per worker), and thus a larger share of consumption in GDP. Of course, this tendency will almost certainly be offset by an ongoing increase in capital intensity, even in the service sector. Obviously there are other, totally moot, considerations. Will leisure time activities be especially capital intensive (grandiose hotels, enormous cruise ships) or the opposite (growing marigolds, reading poetry)? Show me an economist with a strong opinion about these things, and I will show you that oxymoron: a daredevil economist.

Of course if you really do think the capital-labor ratio will be falling, investment behavior is going to disappoint for a long time to come. The shift to intangible capital will strengthen that tendency all the more.

p.s. Leisure will become especially capital-intensive, at least in the United States.

Here is the full essay, from a few years ago, but I think new on-line, and from this MIT Press book of collected essays, now forthcoming in paperback.

Very real progress on the market concentration debate

As you might expect, it is coming from Chang Tsai-Hsieh and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, here is their abstract:

The rise in national industry concentration in the US between 1977 and 2013 is driven by a new industrial revolution in three broad non-traded sectors: services, retail, and wholesale. Sectors where national concentration is rising have increased their share of employment, and the expansion is entirely driven by the number of local markets served by firms. Firm employment per market has either increased slightly at the MSA level, or decreased substantially at the county or establishment levels. In industries with increasing concentration, the expansion into more markets is more pronounced for the top 10% firms, but is present for the bottom 90% as well. These trends have not been accompanied by economy-wide concentration. Top U.S. firms are increasingly specialized in sectors with rising industry concentration, but their aggregate employment share has remained roughly stable. We argue that these facts are consistent with the availability of a new set of fixed-cost technologies that enable adopters to produce at lower marginal costs in all markets. We present a simple model of firm size and market entry to describe the menu of new technologies and trace its implications.

This is likely to prove one of the most important papers of the year, here is the pdf link. The authors open with the example of The Cheesecake Factory, and also health care:

The standardization of production over a large number of establishments that has taken place in sit-down restaurant meals due to companies such as the Cheesecake Factory has taken place in many non-traded sectors. Take hospitals as another example. Four decades ago, about 85% of hospitals were single establishment non-profits. Today, more than 60% of hospitals are owned by forprofit chains or are part of a large network of hospitals owned by an academic institution (such as the University of Chicago Hospitals).

And:

…rising concentration in these sectors is entirely driven by an increase the number of local markets served by the top firms.

Here is a key point:

…we find that total employment rises substantially in industries with rising concentration. This is true even when we look at total employment of the smaller firms in these industries. This evidence is consistent with our view that increasing concentration is driven by new ICT-enabled technologies that ultimately raise aggregate industry TFP. It is not consistent with the view that concentration is due to declining competition or entry barriers, as suggested by Gutierrez and Philippon (2017) and Furman and Orszag (2018), as these forces will result in a decline in industry employment.

This is interesting too, and it departs from say what Amazon is doing:

…we show that the top firms in the economy as a whole have become increasingly specialized in narrow set of sectors, and these are precisely the non-traded sectors that have undergone an industrial revolution. At the same time, top firms have exited many sectors. The net effect is that there is essentially no change in concentration by the top firms in the economy as a whole. The “super-star” firms of today’s economy are larger in their chosen sectors and have unleashed productivity growth in these sectors, but they are not any larger as a share of the aggregate economy.

The paper is titled “The Industrial Revolution in Services.“

Special Features of the Baumol Effect

I explained the Baumol effect in an earlier post based on Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?. In this post, I want to point out some special features of the Baumol effect that help to explain the data. Namely:

- The Baumol effect predicts that more spending will be accompanied by no increase in quality.

- The Baumol effect predicts that the increase in the relative price of the low productivity sector will be fastest when the economy is booming. i.e. the cost “disease” will be at its worst when the economy is most healthy!

- The Baumol effect cleanly resolves the mystery of higher prices accompanied by higher quantity demanded.

First, in the literature on rising prices it’s common to contrast massive increases in spending with little to no increases in quality, as for example, in contrasting education expenditures with mostly flat test scores (see at right). We have spent so much and gotten so little! Cui Bono? It must be teacher unions, administrators or the government!

All of that could be true but the Baumol effect predicts that more spending will be accompanied by no increase in quality. Go back to the classic example of the string quartet which becomes more expensive because labor in other industries increases in productivity over time. The price of the string quartet rises but does anyone expect that the the quality rises? Of course not. In the classic example the inputs to string quartet playing don’t change. The wages of the players rise because of productivity increases in other industries but we don’t invest any more real resources in string quartet playing and so we should not expect any increases in quality.

In just the same way, to the extent that greater spending on education, health care, or car repair is due to the rising opportunity costs of inputs we should not expect any increase in quality. (Note that increases in real resource use such as more teachers per student should result in increases in quality (and perhaps they do) but by eliminating the price increase portion of the higher spending we have eliminated a large portion of the mystery of higher spending with no increase in quality.)

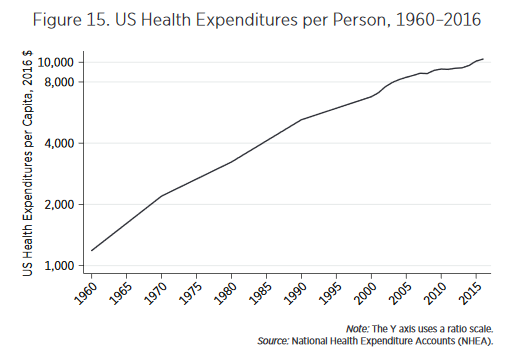

Second, explanations of rising prices that focus on bad things such as monopoly power or rent seeking tend to imply that price increases should be largest when the economy is doing poorly. In contrast, the Baumol effect predicts that increases in relative prices will be largest when the economy is booming. Consider health care. From news reports you might think that health care costs have gotten more “out of control” over time. In fact, the fastest increases in health care costs were in the 1960s. The graph at left is on a ratio scale so slopes indicate rates of growth and what one sees is that the growth rate of health expenditures per person is slowing. That might seem good but remember, from the Baumol point of view, the decline in relative price growth reflects slowing growth elsewhere in the economy.

Second, explanations of rising prices that focus on bad things such as monopoly power or rent seeking tend to imply that price increases should be largest when the economy is doing poorly. In contrast, the Baumol effect predicts that increases in relative prices will be largest when the economy is booming. Consider health care. From news reports you might think that health care costs have gotten more “out of control” over time. In fact, the fastest increases in health care costs were in the 1960s. The graph at left is on a ratio scale so slopes indicate rates of growth and what one sees is that the growth rate of health expenditures per person is slowing. That might seem good but remember, from the Baumol point of view, the decline in relative price growth reflects slowing growth elsewhere in the economy.

Third, holding all else equal, the only rational response to an ordinary cost increase is to substitute away from the good. But in many rising price sectors we see not only greater expenditures (driven by increased prices and inelastic demand) but also greater quantity demanded. As I showed earlier, for example, we have increased the number of doctors, nurses and teachers per capita even as prices have risen. John Cochrane correctly noted that this is puzzling but it’s a bigger puzzle for non-Baumol theories than for Baumol. For non-Baumol theories to explain increases in the quantity purchased, we need two theories. One theory to explain the increase in price (bloat/regulation etc.) and another theory to explain why, despite the increase in price, people are still purchasing more (e.g. income effect). The world is a messy place and maybe that is what is happening. But the Baumol effect offers a cleaner answer.

A Baumol increase in relative price is always accompanied by higher income so it’s much easier to explain how price increases can accompany increases in quantity as well as increases in expenditure. The Baumol story for increased purchase of medical care even as prices increase, for example, is no more mysterious than why people can take more leisure when wages increase–namely the higher wage means a higher income for any given hours and people choose to take some of this higher income in leisure. Similarly, higher productivity in say goods production increases income at any given production level and people choose to take some of this higher income in services.

Summing up, if we examine each sector–education, health care, the arts, etc.–on its own then there are always many possible explanations for why prices might be increasing. Many of these explanations have true premises–there are a lot of administrators in higher education, health care is highly regulated, lower education is government run. But, on closer inspection the arguments often don’t fit the data very well. Prices were increasing before administrators were important, health care is highly regulated but so is manufacturing, private education is also increasing in price, the arts are not highly regulated. It’s impossible to knock down each of these arguments in every industry, so there is always room for doubt. Indeed, the great difficult is that these factors often do result in higher costs and greater inefficiency but I believe those are predominantly level effects not effects that accumulate over time. Moreover, when one considers the rising price industries as a whole these explanations begin to look ad hoc. In contrast, the Baumol effect appears capable of explaining the pricing behavior of a wide variety of industries over a long period of time using a simple but powerful and unified theory.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

The Indian School of Public Policy

India is changing very rapidly and launching new programs and policies at breakneck pace–some reasonably well thought out, others not so well thought out. Historically, India has relied on a small cadre of IAS super-professionals–the basic structure goes back to Colonial times when a handful of Englishmen ruled the country–who are promoted internally and are expected to be generalists capable of handling any and all tasks. The quality of the IAS is unparalleled, of the 1 million people who typically write the Civil Services Exam the IAS accepts only about 180 candidates annually and there are less than 5000 IAS officers in total. But 5,000 generalists are not capable of running a country of over 1 billion people and and India’s bureaucracy as a whole is widely regarded as being slow and of low quality. The quality of the bureaucracy must increase, deep experts in policy must be encouraged and brought in on a lateral basis and there needs to be greater circulation with and understanding of the private sector.

The Indian government has started to show significant interest in hiring people from outside the bureaucratic ranks. NITI Aayog, the in-house government think tank, which replaced the Planning Commission, has hired young graduates from the world’s top universities as policy consultants. The Prime Minister Fellowship Scheme is an interesting initiative to attract young people to policymaking. A range of government departments and ministries do hire young, bright graduates in various disciplines to engage in research and advisory services. In fact, in a marked departure from tradition, the Indian government recently recruited 9 people working in the private sector into their joint secretary level (senior bureaucrats). Nine people doesn’t sound like a lot but these are hires at the top of the pyramid and

[T]his is perhaps the first time that a large of group of experts with domain knowledge will enter the government through the lateral-entry process.

The demand for policy professionals is there. What about the supply? I am enthusiastic about The Indian School of Public Policy, India’s newest policy school and the first to offer a post-graduate program in policy design and management. The ISPP has brought academics, policymakers and business professionals and philanthropists together to build a world-class policy school. I am an academic adviser to the school along with Arvind Panagariya, Shamika Ravi, Ajay Shah and others. The faculty includes Amitabh Mattoo, Dipankar Gupta, Parth J. Shah and Seema Chowdhry among others. Nandan Nilekani, Vallabh Bhansali and Jerry Rao are among the school’s supporters.

The ISPP opens this year with a one-year postgraduate program in Policy, Design & Management. More information here.

If the gdp deflator is off, which financial investments should you make?

Many people suggest that we are under-measuring the benefits of innovation, and thus real rates of economic growth are much higher than we think. That in turn means the gdp deflator is off and real rates of interest are considerably higher than we think. Someday we will all realize the truth and asset prices will adjust.

Let’s say that view is correct (not my view, by the way), how should that change your investment decisions?

One implication, it seems to me, is that you should short the goods and services which are being produced so rapidly under this regime. If that is hard to do, short their substitutes. Say the new innovative growth is coming from the internet sector, and internet activity is a good substitute for collecting stamps (which seems to be true), well short stamps if you can. At least get them out of your diversified portfolio.

Similarly, you may wish to invest in companies which produce goods not easily substituted for over the internet. One observer has mentioned “perfume” to me in this connection, though I do not have the expertise to render a judgment.

More generally, if real rates of return are high, but not perceived as high by most investors (who are still victims of fallacious “great stagnation” arguments and the like), at some point those investors will learn. With more rapid growth enriching the future, and with the realization of such, there will be a sudden demand to shift funds into the present, so as to equalize marginal utilities. So bond prices will fall and that means you should short bonds and buy puts on bonds.

Don’t load up on land and public utilities. Incumbent firms also may fall in value.

You also might fear this new technological progress will bring some fantastic but hard-to-afford new goods and services. How about life extension or immortality but priced at $10 million? The way to hedge that risk is to invest in life extension companies, but even more than their earnings prospects might dictate. That is the best way to insure against life extension being too costly to afford. Note that poorer investors should do this, but the very wealthy do not need to.

What else?

I thank B. and S. and Alex T. for relevant discussions connected to this post.

The Big Push Failed

In 2004, Jeff Sachs and co-authors revived an old theory to explain Africa’s failure to develop, the poverty trap, and an old solution, the big push.

Our explanation is that tropical Africa, even the well-governed parts, is stuck in a poverty trap, too poor to achieve robust, high levels of economic growth and, in many places, simply too poor to grow at all. More policy or governance reform, by itself, will not be sufficient to over-come this trap. Specifically, Africa’s extreme poverty leads to low national saving rates, which in turn lead to low or negative economic growth rates. Low domestic saving is not offset by large inflows of private foreign capital, for example foreign direct investment, because Africa’s poor infrastructure and weak human capital discourage such inflows. With very low domestic saving and low rates of market-based foreign capital inflows, there is little in Africa’s current dynamics that promotes an escape from poverty. Something new is needed.

We argue that what is needed is a “big push” in public investments to produce a rapid “step” increase in Africa’s underlying productivity, both rural and urban.

As the title of the blog might suggest, I was skeptical. But even if a big push wasn’t exactly the right idea, I’m all in favor of Big Ideas and Sachs pursued his Big Idea with tremendous skill and media savvy. Pilot programs were soon up and running and then quickly expanded into full programs. In June 2010, the Millennium Villages Project released its first public evaluation and that is when things started to fall apart.

The initial MVP evaluation claimed great success but simply compared some development indicators before and after in the treated villages without comparing to trends elsewhere. In 2010 such a study was completely out of step with contemporary practices in impact evaluation. Red flag! Clemens and Demombynes showed that comparing to trends elsewhere significantly moderated the impact. A second MVP paper was published in the Lancet but then was quickly retracted when Bump, Clemens, Demombynes and Haddad demonstrated that it had significant errors. Clemens and Demombynes wrote a summary piece on the controversy then in an astounding and under-reported scandal the MVP tried to stifle Clemens and Demombynes. The MVP, with Jeff Sachs at the head, also sicced their lawyers on Nina Munk and her book, The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty. More red flags.

Yet, despite all of this controversy and bad behavior, the MVP project continued to move ahead and in 2012, the UK Department for International Development (DFID) funded US $11 million into an MVP in Northern Ghana that ran until December 2016. Under the auspices of the DFID, we now finally have the first in-depth, independent evaluation of one MVP project and it doesn’t look great. The project did some good but the big push failed and the good that was done could have been done at lower cost.

Overall, the MVP in northern Ghana did not achieve the overall MDG target to reduce extreme poverty and hunger at the local level. Where there are attributable changes to the MDG targets, these tended to be the more limited changes than those that will fundamentally improve people’s health, educational and other outcomes. For instance, the project did increase attendance at primary school (Goal 2) but did not go beyond this MDG and improve the learning outcomes of children; the project did increase the proportion of births attended by professionals and women said to be using contraceptive methods (MDG indicators), but it is not possible to assess the effect on maternal health (Goal 5); and the project did increase the number of toilets (a target under Goal 7), but not beyond this MDG in terms of hygiene and sanitation practices. There are, however, exceptions. The project had a remarkable impact on stunting, which is a long-term health indicator and a predictor of socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood.

So the MVP had some good effects on some indicators:

But is this impact sufficient given the size of the investment? And, by doing everything together, is there a synergistic effect that offers greater value for money than would arise through implementing individual sector-based interventions? In our cost-effectiveness analysis, we demonstrate that the project has so far not yielded sufficiently positive results, and what has been achieved could have been attained at a substantially lower cost (even when we take account of investments made for future usage). As such, the project seems to have fallen short of producing a synergistic effect; and the impact is not large enough for the project to be regarded as cost-effective, even when each sector is assessed independently of the others. Of course, in the longer run, the MVP may produce welfare gains. Importantly the investments in improving the health care service may enhance health outcomes later on; or other considerable investments in infrastructure (roads, health and school facilities) may have an impact on future outcomes.

Perhaps then, the most concerning findings are the early indications that the MVP approach will be difficult to be sustained by district institutions and at the community level; and there are signs that any gains made under the project are already being undermined.

Addendum: Andrew Gelman and co-authors, including Jeff Sachs, offer a broadly similar although less negative in tone evaluation of the entire MVP project.

The rant against Amazon and the rant for Amazon

Wow! It’s unbelievable how hard you are working to deny that monopsony and monopoly type market concentration is causing all all these issues. Do you think it’s easy to compete with Amazon? Think about all the industries amazon just thought about entering and what that did to the share price of incumbents. Do you think Amazon doesn’t use its market clout and brand name to pay people less? Don’t the use the same to extract incentives from politicians? Corporate profits are at record highs as a percent of the economy, how is that maintained? What is your motivation for closing your eyes and denying consolidation? It doesn’t seem that you are being logical.

That is from a Steven Wolf, from the comments. You might levy some justified complaints about Amazon, but this passage packs a remarkable number of fallacies into a very small space.

First, monopsony and monopoly tend to have contrasting or opposite effects. To the extent Amazon is a monopsony, that leads to higher output and lower prices.

Second, if Amazon is knocking out incumbents that may very well be good for consumers. Consumers want to see companies that are hard for others to compete with. Otherwise, they are just getting more of the same.

Third, if you consider markets product line by product line, there are very few sectors where Amazon would appear to have much market power, or a very large share of the overall market for that good or service.

Fourth, Amazon is relatively strong in the book market. Yet if a book is $28 in a regular store, you probably can buy it for $17 on Amazon, or for cheaper yet used, through Amazon.

Fifth, Amazon takes market share from many incumbents (nationwide) but it does not in general “knock out” the labor market infrastructure in most regions. That means Amazon hire labor by paying it more or otherwise offering better working conditions, however much you might wish to complain about them.

Sixth, if you adjust for the nature of intangible capital, and the difference between economic and accounting profit, it is not clear corporate profits have been so remarkably high as of late.

Seventh, if Amazon “extracts” lower taxes and an improved Metro system from the DC area, in return for coming here, that is a net Pareto improvement or in any case at least not obviously objectionable.

Eighth, I did not see the word “ecosystem” in that comment, but Amazon has done a good deal to improve logistics and also cloud computing, to the benefit of many other producers and ultimately consumers. Book authors will just have to live with the new world Amazon has created for them.

And then there is Rana Foroohar:

“If Amazon can see your bank data and assets, [what is to stop them from] selling you a loan at the maximum price they know you are able to pay?” Professor Omarova asks.

How about the fact that you are able to borrow the money somewhere else?

Addendum: A more interesting criticism of Amazon, which you hardly ever hear, is the notion that they are sufficiently dominant in cloud computing that a collapse/sabotage of their presence in that market could be a national security issue. Still, it is not clear what other arrangement could be safer.

Dan Wang on how technology grows

It is a short essay, here are a few scattered bits:

The real output of the US manufacturing sector is at a lower level than before the 2008 recession; that means that there has not been real growth in US manufacturing for an entire decade. (In fact, this measure may be too rosy—the ITIF has put forward an argument that manufacturing output measures are skewed by excessive quality adjustments in computer speeds. Take away computers, which fewer and fewer people are buying these days, and US real output in manufacturing would be meaningfully lower.) Manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at nearly 20 million workers; it fell to 17 million in 2000, 14 million in 2008, and stands at 12 million today. The US population has grown by 40% since 1979, while the number of manufacturing workers has nearly halved.

And:

I think we should try to hold on to process knowledge.

Japan’s Ise Grand Shrine is an extraordinary example in that genre. Every 20 years, caretakers completely tear down the shrine and build it anew. The wooden shrine has been rebuilt again and again for 1,200 years. Locals want to make sure that they don’t ever forget the production knowledge that goes into constructing the shrine. There’s a very clear sense that the older generation wants to teach the building techniques to the younger generation: “I will leave these duties to you next time.”

And:

There’s an entertaining line in the Brad Setser piece I linked to earlier. He tells us that one of the reasons that the US has such a high surplus in the services trade is that Americans have a low propensity to travel abroad. I don’t view that as a great way to earn a trade surplus.

There is much more at the link.

Will monetary tightening halt the labor market recovery?

My latest Bloomberg column is on that topic, here is one bit:

…these days more and more economists, especially those with Keynesian sympathies, are insisting that higher legal minimum wages don’t lower employment much, if at all. If higher real wages don’t much hurt employment, we shouldn’t expect lower real wages to much boost employment. This “new wisdom” on minimum wages contradicts Keynesian labor economics and implies inflation won’t much boost employment, if at all.

And:

One thing we do know about inflation is that voters hate it. Economists sometimes treat this belief as irrational, assuming that workers in aggregate will get raises to compensate for the higher prices. This is true for many top performers, whose income growth would exceed inflation regardless. But a lot of other workers are concentrated in somewhat bureaucratic service-sector jobs, they have weak bargaining power, and their pay is not indexed to inflation. If the rate of price inflation is 4 percent rather than 2 percent, for many people that means their take-home pay is worth 2 percentage points less than it would have been under modest inflation.

And this:

Most discussions about monetary policy aren’t about economic theory (properly understood) at all. Rather they are about blaming the system, as people feel a sense of outrage that somehow someone isn’t trying hard enough to fix basic problems. Most of the claims out there, when put under the microscope of reason, dissolve into a beautiful, brilliant agnosticism.

Here is the full column. Note that Bloomberg now has a paywall, with I believe ten free articles per month. Here is information on subscription offers, I urge you all to increase the velocity of money.

The China Shock was Matched by a China Boom

We have always known that trade and technology shocks destroy some jobs and create others with the change in equilibrium typically being zero net job losses and a net positive effect on wages. Increases in imports, for example, should be matched sooner or later by increases in exports as foreigners aren’t sending us goods for nothing. The China Shock paper of Autor, Dorn and Hanson seemed to suggest that the job losses were not matched by job gains. The paper’s clever identification strategy, however, was much stronger on identifying the losses than the offsetting gains (see e.g. Scott Sumner.)

New research by Feenstra, Ma and Xu and Feenstra and Sasahara (summarized here) shows, that as theory predicts, there were offsetting gains. Feenstra, Ma and Xu use similar techniques to ADH and find big offsetting increases in exports:

Our empirical results show important job gains due to US export expansion. We find that although imports from China reduce jobs, the global export expansion of US products creates a considerable number of jobs. Based on the industry-level estimation, our results show that on balance over the entire 1991-2007 or 1991-2011 periods, job gains due to changes in US global exports largely offset job losses due to China’s imports, resulting in about 300,000 to 400,000 job losses in net. Estimation at the commuting zone level generate even bigger job creation effects: in net, global export expansion substantially offsets the job losses due to imports from China, resulting in about 200,000 net job losses over the period 1991-2007, and a roughly balanced net effect if we extend the analysis to 1991-2011.

(Note that the net job loss figures are rounding error in an economy where there are millions of hires and separations every month).

Using a second, quite different, approach based on input-output calculations they find similar results in manufacturing but an even bigger effect on services:

We find that the growth in US exports created demand for 2 million manufacturing jobs, 500,000 resource-sector jobs, and a remarkable 4.1 million jobs in services, totalling 6.6 million. The positive job creation effect of exports in the manufacturing sector, 2 million, is quantitatively similar to the result in Feenstra et al. (2017), in which 1.9 million jobs were created by US exports from the instrumental-variable regression approach. On the import side, our analysis shows that manufacturing imports from China reduced demand for US jobs by 1.8-2.0 million, which is similar to the result in Autor et al. (2016), who finds a decline of 2.0 million jobs due to imports from China.

The authors conclude:

Our results fit the textbook story that job opportunities in exports make up for jobs lost in import-competing industries, or nearly so. Once we consider the export side, the negative employment effect of trade is much smaller than is implied in the previous literature. Although our analysis finds net job losses in the manufacturing sector for the US, there are remarkable job gains in services, suggesting that international trade has an impact on the labour market according to comparative advantage. The US has comparative advantages in services, so that overall trade led to higher employment through the increased demand for service jobs.

My Conversation with Douglas Irwin, audio and transcript

Doug’s new book Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy is the greatest book on trade policy ever written, bar none. and also a splendid work of American history more generally. So I thought he and I should sit down to chat, now I have both the transcript and audio.

We covered how much of 19th century American growth was due to tariffs, trade policy toward China, the cultural argument against free trade, whether there is a national security argument for agricultural protectionism, TPP, how new trade agreements should be structured, the trade bureaucracy in D.C., whether free trade still brings peace, Smoot-Hawley, the American Revolution (we are spoiled brats), Dunkirk, why New Hampshire is so wealthy, Brexit, Alexander Hamilton, NAFTA, the global trade slowdown, premature deindustrialization, and the history of the Chicago School of Economics, among other topics. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Here goes. The claim that 19th century American growth was driven by high tariffs. What’s your take?

IRWIN: Not really true. If you look at why the US economy performed very well, particularly relative to Britain or Germany or other countries, Steve Broadberry’s shown that a lot of the overtaking of Britain in terms of per capita income was in terms of the service sector.

The service sector was expanding rapidly. It had very high productivity growth rates. We usually don’t think as that being affected by the tariff per se. That’s one reason.

We had also very high productivity growth rates in agriculture. I’ve done some counterfactual simulations. If you remove the tariff, how much resources would we take out of manufacturing and put into services or agriculture is actually pretty small. It just doesn’t account for the success we had during this period.

COWEN: Is there any country where you would say, “Their late 19th century economic growth was driven by tariffs?” Argentina, Canada, Germany, anything, anywhere?

IRWIN: No. If you look at all those, once again, in late 19th century, they were major exporters, largely of commodities, but they did very well that way. You know that Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world in the late 19th century. It really wasn’t until they adopted more import substitution policies after World War I that they began to fall behind.

Definitely recommended, and here is Doug’s Wikipedia page.

What it would take to change my mind on net neutrality

Keep in mind, I’ve favored net neutrality for most of my history as a blogger. You really could change my mind back to that stance. Here is what you should do:

1. Cite event study analysis showing changes in net neutrality will have significant and possibly significantly negative effects.

2. Discuss models of natural monopoly, and how those market structures may or may not distort product choice under a variety of institutional settings.

3. Start with a framework or analysis such as that of Joshua Gans and Michael Katz, and improve upon it or otherwise modify it. Here is their abstract:

We correct and extend the results of Gans (2015) regarding the effects of net neutrality regulation on equilibrium outcomes in settings where a content provider sells its services to consumers for a fee. We examine both pricing and investment effects. We extend the earlier paper’s result that weak forms of net neutrality are ineffective and also show that even a strong form of net neutrality may be ineffective. In addition, we demonstrate that, when strong net neutrality does affect the equilibrium outcome, it may harm efficiency by distorting both ISP and content provider investment and service-quality choices.

Tell me, using something like their framework, why you think the relative preponderance of costs and benefits lies in one direction rather than another.

Consider Litan and Singer from the Progressive Policy Institute, they favor case-by-case adjudication, tell me why they are wrong.

Or read this piece by Nobel Laureate Vernon Smith, regulatory experts Bob Crandall, Alfred Kahn, and Bob Hahn, numerous internet experts, etc.:

In the authors’ shared opinion, the economic evidence does not support the regulations proposed in the Commission’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking Regarding Preserving the Open Internet and Broadband Industry Practices (the “NPRM”). To the contrary, the economic evidence provides no support for the existence of market failure sufficient to warrant ex ante regulation of the type proposed by the Commission, and strongly suggests that the regulations, if adopted, would reduce consumer welfare in both the short and long run. To the extent the types of conduct addressed in the NPRM may, in isolated circumstances, have the potential to harm competition or consumers, the Commission and other regulatory bodies have the ability to deter or prohibit such conduct on a case-by-case basis, through the application of existing doctrines and procedures.

4. Consider and evaluate other forms of empirical evidence, preferably not just the anecdotal.

5. Don’t let emotionally laden words do the work of the argument for you.

6. Offer a rational, non-emotive discussion of why pre-2015 was such a bad starting point for the future, and why so few users seemed to mind or notice as the regulations switched several times.

7. Don’t let politics make you afraid to use your best argument, namely that anti-NN types typically develop more faith in an assortment of government regulators in this setting than they might express in a number of other contexts. That said, don’t just use this point to attack them, live with and consistently apply whatever judgment of the regulators you decide is appropriate.

If you are wondering why I have changed my mind, it is a mix of new evidence coming in, experience over the 2014-present period, relative assessment of the arguments on each side moving against NN proponets, and the natural logic of the embedded trade-offs, whereby net neutrality typically works in a short enough short run but over enough time more pricing is needed. Of course it is a judgment call as to when the extra pricing should kick in.

Here is what will make your arguments less persuasive to me:

1. Respond to discussions of other natural monopoly sectors and their properties by saying “the internet isn’t like that, you don’t understand the internet.” If someone uses the water sector to make a general point about tying and natural monopoly, commit internet error #7 by responding: “the internet isn’t like water! You don’t understand the internet!”

2. Lodge moral complaints against the cable companies or against commercial incentives more generally, or complain about the “ideology” of others. Mention the word “Trump” or criticize the Trump administration for its failings. Call the recent decision “anti-democratic.”

3. Cite nightmare or dystopian scenarios that are clearly illegal under other current laws and regulations. Cite dystopian scenarios that would contradict profit-maximizing behavior on the part of the involved companies. Assume that no future evolution of regulation could solve or address any of the problems that might arise from the recent switch. Mention Portugal as a scare scenario, without explaining that full internet packages still are for sale there, albeit without the discounts for the partial packages.

Are you up to the challenge?

If I read say this Tim Wu Op-Ed, I think it is underwhelming, even given its newspaper setting, and the last two paragraphs are content-less, poorly done emotive manipulation. Senpai 3:16 is himself too polemic and exaggerated, but he does make some good points against this piece, see his Twitter stream.

Net neutrality defenders, as of now you have lost this battle. I’d like to hear more.