Emmanuel Saez wins the Clark medal

Here is one report. Otherwise, at Berkeley, Carl Shapiro is leaving to do antitrust analysis in Washington and Brad DeLong suggests that Joseph Farrell is also leaving Berkeley for the Obama administration.

The substitution of capital for labor, charity edition, seen in Atlanta

Debating Economics

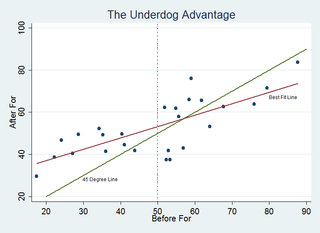

Intelligence Squared has held a series of debates in which they poll ayes and nayes before and after. How should we expect opinion to change with such debates? Let’s assume that the debate teams are evenly matched on average (since any debate resolution can be written in either the affirmative or negative this seems a weak assumption). If so, then we ought to expect a random walk; that is, sometimes the aye team will be stronger and support for their position will grow (aye after – aye before will increase) and sometimes the nay team will be stronger and support for their position will grow. On average, however, we ought to expect that if it’s 30% aye and 70% nay going in then it ought to be 30% aye and 70% nay going out, again, on average. Another way of saying this is that new information, by definition, should not swing your view systematically one way or the other.

Alas, the data refute this position. The graph shown below (click to enlarge) looks at the percentage of ayes and nayes among the decided  before and after. The hypothesis says the data should lie around the 45 degree line. Yet, there is a clear tendency for the minority position to gain adherents – that is, there is an underdog advantage so positions with less than 50% of the ayes before tend to increase in adherents and positions with greater than 50% ayes tend to lose adherents. What could explain this?

before and after. The hypothesis says the data should lie around the 45 degree line. Yet, there is a clear tendency for the minority position to gain adherents – that is, there is an underdog advantage so positions with less than 50% of the ayes before tend to increase in adherents and positions with greater than 50% ayes tend to lose adherents. What could explain this?

I see two plausible possibilities.

1) If the side with the larger numbers has weaker adherents they could be more likely to change their mind.

2) The undecided are key and the undecided are lying.

For case 1, imagine that 10% of each group changes their minds; since 10% of a larger number is more switchers this could generate the data. The problem with 1 and with the data more generally is that we don’t seem to see a tendency towards 50:50 in the world. We focus on disputes, of course, but more often we reach some consensus (the moon is not made of blue cheese, voodoo doesn’t work and so forth).

Thus 2 is my best guess. Note first that the number of “undecided” swing massively in these debates and in every case the number of undecided goes down a lot, itself peculiar if people are rational Bayesians. A big swing in undecided votes is quite odd for two additional reasons. First, when Justice Roberts said he’d never really thought about the constitutionality of abortion people were incredulous. Similarly, could 30% of the audience (in a debate in which Tyler recently participated (pdf)) be truly undecided about whether “it is wrong to pay for sex”? Second, and even more doubtful, could it be that 30% of the people at the debate were undecided–thus had not heard arguments in let’s say the previous 10 years that converted them one way or the other–but on that very night a majority of the undecided were at last pushed into the decided camp? I think not, thus I think lying best explains the data.

Some questions for readers. Can you think of another hypothesis to explain the data? Can you think of a way of testing competing hypotheses? And does anyone know of a larger database of debate decisions with ayes, nayes and undecided before and after?

Hat tip to Robin for suggesting that there might be a tendency to 50:50, Bryan and Tyler for discussion and Robin for collecting the data.

The Education of the Stoic

"I am shy with women: therefore there is no God" is highly unconvincing metaphysics.

That's from Fernando Pessoa's book, written under the name of Baron of Teive.

Markets in everything, photographs only edition

Most folks never realize how cute microbes can be when expanded

1,000,000 times and then fashioned into cuddly plush. Until now, that

is. Keep one on your desktop to remind yourself that there is an

"invisible" universe out there filled with very small things that can

do incredible damage to much bigger things. Then go and wash your

hands. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Here is the web site. The options include human sperm, toxic mold, and, best of all, gangrene. If you read closely it seems you only get a picture, not the real thing.

I thank TheBrowser for the pointer.

False Economy, by Alan Beattie

I enjoyed the book, most of all the chapter comparing Argentina and the United States. I was struck by this bit:

New York is the only one out of the sixteen largest cities in the northeastern or midwestern states whose population is larger than it was fifty years ago.

Over that same time period our national population has roughly doubled. The subtitle of the book is A Surprising Economic History of the World.

Gerry Gunderson and the battle at Trinity College

In one previously undisclosed fight, Trinity College in Connecticut

is facing government scrutiny for its plan to spend part of a $9

million endowment from Wall Street investing legend Shelby Cullom Davis.

Trinity's Davis professor of business, Gerald Gunderson, says he

believed the plan, which would have funded scholarships for

international students, violated the wishes of the late Mr. Davis. He

alerted the Connecticut attorney general's office. Then, Mr. Gunderson

said in notes submitted to the agency, Trinity's president summoned him

to the school's cavernous Gothic conference room, where he called the

professor a "scoundrel" and threatened not to reappoint him.

Gunderson is a market-oriented economist; here is the full story.

Handicappling the Clark medal

Justin Lahart reports:

Friday, the American Economic Association will present the John Bates Clark medal, awarded to the nation’s most promising economist under the age of 40.

The Clark is often a harbinger of things to come. Of the 30 economists who have won it, 12 have gone on to win the Nobel, including last year’s Nobel winner, Paul Krugman. Other past winners include White House National Economic Council director Lawrence Summers and Steve Levitt, of Freakonomics fame. Since it was first awarded in 1947, the Clark has been given out every two years, but beginning next year it will be given out annually.

With a deep pool of young talent to draw from, there’s no sure winner. But among economists, the clear favorite is Esther Duflo, 36, who leads the Massachusetts Institute of Technology‘s Jameel Poverty Action Lab with MIT colleague Abhijit Banerjee.

Ms. Duflo has been at the forefront of the use of randomized experiments to analyze the effectiveness of development programs. If teacher attendance is a problem in rural India, for example, what happens if teachers are given cameras with date and time stamps and told to take a picture of themselves and their students each morning and afternoon? Ms. Duflo and economist Rema Hanna tried it out and found that in the “camera schools,” teacher absences fell sharply and student test scores improved. Does giving poor mothers 60 cents worth of dried beans as an incentive to immunize their children work? It works astoundingly well. By answering these kinds of problems, Ms. Duflo, her colleagues, and the many economists around the world she has helped inspire, are uncovering ways to make sure that money spent on helping poor people in developing countries is used effectively.

Harvard University‘s Sendhil Mullainathan, who founded the Poverty Action Lab with Ms. Duflo and Mr. Banerjee, is also likely on the Clark short list. He’s a leading light in the fast-growing field of behavioral economics, studying ways that psychology influences economic decisions. For one paper, he and frequent co-author Marianne Bertrand sent out fictitious resumes in response to want ads, randomly assigning each resume with very African American sounding or very white sounding names. The resumes with the very white names got far more call backs. Mr. Mullainathan, 36, is also applying behavioral economics insights to development problems. One insight: The behavioral weaknesses of the very poor are no different than the weaknesses of people in all walks of life, but because the poor have less margin for error, their behavioral weaknesses can be much more costly.

Emanuel Saez at the University of Calif.-Berkeley, another Clark candidate, has been tenaciously researching the causes of wealth and income inequality around the world, with a focus on the what’s happening at the very tip of the wealth pyramid. But because there is very little data on the very rich, Mr. Saez, 36, and his frequent co-author Thomas Piketty have combed through income tax figures to come up with historic estimates. Among their findings: That before the onset of the financial crisis, the income share of the top 1% of families by income accounted for nearly a quarter of U.S. income – the largest share since the late 1920s.

You’re a bastard

According to one recent study, the portfolio effect dominates:

You might expect that being prompted (primed) to think of yourself as a good person would make you more altruistic or moral – but, in fact, the exact opposite appears to be

the case. Primed to think about what a good person you are, your most

likely reaction is to think you’ve paid your morality dues and go on

about your business.

The underlying model is this:

According to a new study in Psychological Science,

humans engage in a process called “moral self-regulation.” Basically,

we’re constantly calculating the trade-off between being able to see

ourselves as good people and the cost of engaging in all that

non-advantageous goodness.

Assorted links

1. Depression fear vs. fear of spiders.

2. What predicts orchiectomies?

3. Is U.S. infrastructure really so bad?

4. SSRN listing for papers from the Milton Friedman Institute.

5. What does the Kindle hardware cost? $185.49, perhaps.

6. New Thomas Pynchon novel due in August.

One thought about the IMF

I believe this point has not received sufficient attention:

In a twist that leaves some experts shaking their heads, the fund needs

money from cash-rich developing countries, like China and India, to

help more developed but strapped countries, like those in Eastern

Europe.

One possibility is that the recent IMF loan program is about making governments better off, not about making people better off. Can you imagine that?

Timothy Geithner: a study in facial micro-expressions

Here is the source article. Here is an interesting article about judging creditworthiness by a person's looks. How different would the politics be if Geithner looked like Scarlett Johansson? Would that make the case against bank nationalization more persuasive?

Here is a sample of pictures. This, I think, is the least nervous-looking one.

Authentication markets in everything

"Nothing is too mundane to be authenticated, if deemed potentially

valuable. Cans of insect repellent used to combat the midges that

swarmed the 2007 playoffs in Cleveland were authenticated. So were

urinals pulled from the old Busch Stadium in St. Louis and office

equipment from since-razed Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. The

Phillies are cutting the clubhouse carpet from last season into

authenticated 18-by-24-inch mats. "

Indeed, "…every game has

at least one authenticator, watching from a dugout or near one. The

authenticators are part of a team of 120 active and retired

law-enforcement officials sharing the duties for the 30 franchises.

Several worked the home openers for the Yankees and the Mets, helping

track firsts at the new stadiums. They verified balls, bases, jerseys,

the pitchers’ rosin bag, even the pitching rubber and the home plate

that were removed after the first game at Yankee Stadium. "

Here is more, from the blog of Al Roth.

Assorted Links

- Hayek v. Keynes in elegant powerpoints developed by Roger Garrison. Hat tip to Taking Hayek Seriously.

- The Independent Review (I am an assistant editor) appears in several scenes in the new Crowe, Affleck movie, State of Play. David Theroux says the movie would have been better had the writers paid more attention to the contents.

Department of Unintended Consequences

The topic is eBay and the antiquities trade. It turns out that looting has gone down, the opposite of what was expected from the expansion of eBay. Supply is so elastic, and so many fakes are made, that looting is less worthwhile than it used to be:

Our greatest fear was that the Internet would democratize antiquities

trafficking and lead to widespread looting. This seemed a logical

outcome of a system in which anyone could open up an eBay site and sell

artifacts dug up by locals anywhere in the world. We feared that an

unorganized but massive looting campaign was about to begin…But a very curious thing has happened. It

appears that electronic buying and selling has actually hurt the

antiquities trade.

…many of the primary

"producers" of the objects have shifted from looting sites to faking

antiquities. I've been tracking eBay antiquities for years now, and

from what I can tell, this shift began around 2000, about five years

after eBay was established. …Today, every grade and

kind of antiquity is being mass-produced and sold in quantities too

large to imagine.

…Because the eBay phenomenon has substantially reduced total costs by

eliminating middlemen, brick-and-mortar stores, high-priced dealers,

and other marginal expenses, the local eBayers and craftsmen can make

more money cranking out cheap fakes than they can by spending days or

weeks digging around looking for the real thing. It is true that many

former and potential looters lack the skills to make their own

artifacts. But the value of their illicit digging decreases every time

someone buys a "genuine" Moche pot for $35, plus shipping and handling.

In other words, because the low-end antiquities market has been flooded

with fakes that people buy for a fraction of what a genuine object

would cost, the value of the real artifacts has gone down as well,

making old-fashioned looting less lucrative.

I thank Lawrence Rothfield for the pointer.