Results for “new service sector” 331 found

Do subsidies protect Obamacare against the adverse selection death spiral?

Jonathan Cohn writes:

What you may not realize (because few people do) is that the subsidies, by design, protect people from rising premiums. The law basically dictates what these folks pay for the typical, “silver-level” Obamacare plan, no matter what the insurer charges. This is critical. It means that rising premiums won’t affect the willingness of those people to enroll—which means, in turn, they’d still have incentive to sign up next year, as long as the technological bugs were gone and Obamacare online was working. (Subsides were a missing element of those ill-fated reform experiments in New Jersey and elsewhere.)

The economics here are tricky. Insurance companies set prices both for those who receive subsidies and for those who do not. Furthermore, the subsidy — when there is a subsidy — is determined by a process akin to a second-price auction, rather than matching the highest price in the market. (How much collusion is there anyway, once all these prices are posted?)

One question is this: pre- “pressures for adverse selection death spiral,” where is the price sitting? I don’t see an a priori answer to this query, so let’s work through two possibilities.

One option is that, at the margin, the price is already high enough that further price hikes would lower insurer profits and subsidies won’t make up for enough of that difference. So the scenario goes like this. A smaller number of “invincibles” sign up early on than initially had been expected, in part because of negative publicity about the exchanges. Providers respond by lowering service quality rather than by raising posted prices.

Think of this as the “price stickiness scenario.” One big reason for holding back on the price, and instead lowering network quality, is the adverse selection problem itself. If some of the invincibles are paying part of the price hike, higher prices will put them off. Yet, if indeed they are invincibles, vague rumors about inferior network access may not put them off much at all. They don’t expect to be using the network anyway. But of course for sick people this change in quality and access will be a problem.

On top of that, might there be some stickiness in the posted price? Many macroeconomists stress price stickiness even under normal circumstances. And that means very often sticky in the upwards direction too, for fear of alienating customers. Prices are all the more sticky in heavily regulated industries and in sectors which are under a good deal of policy debate and media scrutiny and where suppliers are not all that politically popular. Prices are even stickier when there are easy ways of raising “true net price” by lowering quality, raising wait times, restricting access and delivery speed, and so on. Those dimensions of the problem are harder for customers, regulators, and also media-mongers to monitor.

Access restrictions are also a way of checking ultimate financial risk in a way that price increases cannot be. We can thank Joseph Stiglitz for this insight, as Joe pointed out that not only are prices sticky, but quantities can be sticky too, and risk-averse firms may wish to limit how much they are on the hook for.

I see a good chance that the price stickiness scenario holds. And in that case the problem is not so much a price spiral but rather network quality moves to a much lower level and sits there.

I call the second and simpler scenario the “subsidies make up the difference” scenario.

In that scenario, the initial prices are low enough that they can be raised and the subsidies pick up the difference. The companies don’t try to game the adverse selection problem with quality decreases and most would-be buyers are covered by the subsidies at the relevant margin. The thought experiment then runs like this. The initial quality of pool applicants suddenly worsens, but this time the main effect is that posted prices go up. Because of the subsidies the real net prices to potential purchasers do not change very much and all still seems OK.

We do not know which scenario will occur, or to what extent, or in which states. But I hardly think the law is in the clear in this regard.

How Medicare influences private payment systems (model this)

There is a new paper by Jeffrey Clemens and Joshua D. Gottlieb on this topic, the abstract is here:

We analyze Medicare’s influence on private payments for physicians’ services. Using a large administrative change in payments for surgical procedures relative to other medical services, we find that private payments follow Medicare’s lead. On average, a $1 change in Medicare’s relative payments results in a $1.30 change in private payments. We find that Medicare similarly moves the level of private payments when it alters fees across the board. Medicare thus strongly influences both relative valuations and aggregate expenditures on physicians’ services. We show further that Medicare’s price transmission is strongest in markets with large numbers of physicians and low provider consolidation. Transaction and bargaining costs may lead the development of payment systems to suffer from a classic coordination problem. By extension, improvements in Medicare’s payment models may have the qualities of public goods.

This paper, which seems quite sound to me, has a few implications.

First, if you are unhappy with the American health care system, government is more at fault for the problems of the private sector than it may at first appear. We have a much more governmental system than most of its critics care to admit and that goes even beyond government health care spending as a percentage of total health care spending.

Second, we could cut Medicare reimbursement rates, by limiting the doc fix, without old people all very rapidly going to the back of the health care queue.

Third, the authors find that the larger Medicare becomes, the stronger this “pass through” effect generally will be. In other words, this result will be all the more true in our future.

Fourth, the cross-sectoral price transmission result implies that long-run supply elasticities in the sector are not large, which also does not bode well for the future of health care access in an aging society.

Overall this is a depressing paper, although it implies that successful Medicare cost control could have significant cross-sectoral benefits, beyond Medicare itself.

*The Age of Oversupply*

That is Daniel Alpert’s book and the subtitle is Overcoming the Greatest Challenge to the Global Economy. I found this a fun and interesting read and I agreed with more of it than I thought I would. I’ve stressed numerous times that some of the dilemmas of our current day can be understood through nineteenth century parallels and also through the writings of the classical economists. So why not pull Thomas Chalmers and Malthus out of the closet and worry about a general glut of goods and services, juxtaposed with Bernanke’s global savings glut, and a dash of MMT at the end for good measure? The more the merrier, I say.

Here is one representative overview passage from the book:

The supply of global labor and capital is too great, and demand too weak, for them to resume proper functioning without proper assistance. This imbalance has been going on for years and nobody seems to know what to do about it. Private markets haven’t solved the problem, not because they are inherently dysfunctional, but because the sheer magnitude of changes in the global economy, thanks to the fall of the Bamboo and Iron curtains, has created challenges too big for private markets, acting alone, to reasonably address.

I like the integration of the international dimension, but I do have some worries:

1. The book too often lapses out of its international context and falls into standard Keynesianism. I don’t mean to prejudge against that approach, but we’re already pretty familiar with it and it doesn’t justify another book to spell it out. The author should have spent more time in the nineteenth century, in China, or both.

2. Good infrastructure selection, as the author proposes, could boost growth but it won’t undo any general glut that might exist and it won’t help current unemployment a lot. Those are not the workers who would end up being hired to build the new projects. Rather than closing the book with policy prescriptions (always a downer in a trade book), the author should have spelt out a vision for where all this is likely headed. In any case, we’re unlikely to spend another $1.2 trillion on infrastructure over the next five years, so what happens then? Can we depreciate our capital stock back into a more dynamic recovery?

3. Even when I agree with Alpert, I don’t think “oversupply” is what he is pinpointing. Like Krugman’s recent flirtation with demand-side secular stagnation theories, it is an embarrassment for these views that current nominal gdp is considerably higher — more than ten percent — than its pre-crash peak. The price level is higher too. On p.135 Alpert recognizes this problem and even mentions that his own theory may have predicted as much as six percent deflation, which of course isn’t there. He doesn’t have a good explanation on this point and yet it is critical to his overall framing (though not to each and every particular argument).

Yes, I know, many wages won’t fall in nominal terms and that limits price deflation. But it won’t get you the increase in nominal values we have observed, the wage truncation hypothesis has theoretical problems, and also it is failing recent empirical tests. Arnold Kling considers some recent research on the Phillips curve (pdf) and finds it can’t explain why the rate of inflation remained as high as it did, given the recession we experienced. Or take a peek at the recent empirical study by Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Koustas (pdf, interesting on several counts). They find, to put it bluntly: “Hence, there is no missing wage disinflation puzzle to match the missing price disinflation puzzle. This strongly suggests that downward wage rigidity is unlikely to be the key factor underlying the missing disinflation of the Great Recession.” In other words, that whole line of explanation seems to fail and that is going to mean no general glut of goods and services.

Still, I am happy I bought this book. Bravo for the nineteenth century.

Addendum: Alpert replies by email: “As to the price level and wage rigidity – I imagine we have differing views on what is supporting both. I believe I make a reasonable argument that easing has kept financial asset value (incl. real estate) from falling, and that wages haven’t fallen because, ex-Japan, the labor oversupply has been absorbed via high levels of underemployment in advanced economies, rather than by wage reductions. Put it all on a per-capita basis and have another look at aggregate wages. Prices, of course, have fallen in the tradable sectors. And but for rents (incl. owners equiv) (protected by monetary easing), and healthcare and education (guild industries with extensive price interference from third party payor systems), we would not have price stability since the beginning of the great recession.”

From the comments — why are the ACA exchanges behind schedule?

The primary issues are political and legal barriers to properly build a workable solution.

The first is that the ACA gives states the right to build and run their own exchanges. However, even if they rake the money HHS is still required to step in and fill the gap if they fail. So many states took the money (who wouldn’t) but the program is left to implement a system of unknown size. Just that would doom most IT implementations. In addition there weren’t any IT firms interested in helping to tackle the Federal system, instead they went to the bigger states where they don’t have to navigate the crazy laws that govern IT projects at the federal level. This also allowed them to integrate smaller less complex systems outside the gaze of an IG department who publishes reports that get national attention in their zeal to protect public money.

Second is that funding is discretionary and even though they mapped out the required headcount they Didn’t have the budget appropriated to hire even half what was needed (as defined by outside consultants like MITRE) which left them severely understaffed. My wife’s ‘team’ of 5 was actually 2. There is no chance that Congress would appropriate more money to fix this. It also isn’t like these people are all that great at their jobs. No person really good at their job in the private sector is going to take a big pay cut to work for HHS. These jobs aren’t a bunch of overpaid airport security people but are jobs that pay much much better in the private sector. This means promoting the inexperienced from within and there is no institutional experience to implement a complex system.

Next there is the political decision to fold the exchanges into CMS (Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services). The congressional Republicans were using every power they could to harass the executives so HHS tried to shield them behind Medicare. However, it wan’t like CMS was any good at this type of implementation and it was now not the only priority for the contract shops to worry over.

The other problem on a technical level was the near impossible task of verifying eligibility of users for subsidies. All the data has to be verified to avoid fraud, this include income. That data is segregated at the IRS and they are prevented by law from sharing ANY of that information with other parts of the government. Thank Johnson and Nixon for their abuse of IRS info. So there is no easy way to automate the approval process based on tax returns. The only sensible way is to have the IRS do it, but that would require funding and no contract manager is going to go to jail to solve a problem without a new budget appropriated for them.

Last is just the factor that any large IT system like this has a horrible failure rate. Supposedly the success rate in the private sector is now above 50% but there aren’t many major news stories when private companies waste a billion dollars on a system that never does anything. The Government is even worse because of the hundreds of pages of regulations meant to ensure money isn’t “wasted”. Sure, the Federal Government generally gets the best pricing there is on products, but the massive overhead eats all of that up and delays the process by months. I think there is a reason that private companies don’t have the complex rules you see in the government. They also don’t have to worry about going to jail if they do break the rules.

I find it a miracle that there is ANY chance that the exchanges might actually be working in time. However, I think it would be wrong to say that it is some inherently governmental problem that couldn’t be solved with smart reform of the laws and congressional support to fix things. One party is invested in always excusing governmental problems and the other is opposed to the idea of trying to fix problems because they are invested in highlighting government failure for the simple purpose of killing it.

The Autor, Dorn, and Hanson paper on trade and technology

Several other bloggers already have covered this important paper, but there remain underexplored details. Overall the main result is that trade has had more of a negative impact on employment than we used to think. I won’t attempt a summary, but here are a few further results of note:

1. In the Providence, Rhode Island area the trade exposure to China for 2000-2007 went up by $3,490 per worker. For New Orleans the same increase was only $490 per worker.

2. Technology gains and mechanization in a region do not predict employment declines, but they do predict polarization of wage returns. (I do think that automation will create problems for labor markets, but I think that issue is more about our future. It also was true, for a while, in our more distant past, as outlined by David Ricardo.)

3. The negative employment effects of technology on manufacturing jobs peaked in the 1980s, and since have declined. The negative employment effects of technology on service sector jobs have been rising. On net the effect on employment across all sectors has stayed roughly constant over the last few decades.

4. Women and older workers are those most likely to lose their jobs because of technology.

5. The employment effects of exposure of a region to Chinese imports are significant. A good deal of this effect works through the labor force participation rate rather than through measured unemployment per se. This by the way is one indication that the labor force participation rate does contain relevant information about the health of the labor market.

6. The authors classify jobs into the categories of abstract, routine, and manual, and suggest that routine jobs are most vulnerable to automation. Maybe, but I would not take this for granted. Better software in a car can forestall mechanical problems, and thus replace the manual labor of the automobile mechanic, even if we cannot imagine how a robot could itself do the car repair work.

How Medicare payments are set

It’s never a bad idea to bring this point up yet again:

Reporters Peter Whoriskey and Dan Keating have opened Post readers’ eyes to the fact that Medicare pays for physician services — a $69.6 billion item in 2012 — according to an arcane and little-known price list, over which doctors themselves exercise considerable and less-than-totally-transparent influence.

Known as the Relative Value Update, the process consists of a 31-member committee of the American Medical Association (AMA) recommending what Medicare should pay for some 10,000 procedures — with the fees based in part on how long it takes to complete each one. This time-and-motion study often fails to take full account of changing technology and other factors affecting physician productivity, so anomalies result: For example, Medicare pays for a 15-minute colonoscopy as if it took 75 minutes.

Here is a bit more, here is the longer article.

By the way, there is also this new result:

In one of the study’s notable insights, Dr. [Joseph P.] Newhouse said, “we did not find any relation between the quality of care and spending, in either Medicare or the commercial insurance sector.”

That is from a new study of regional variation in Medicare expenditures. The study itself is here, and it seems to imply that regional discrepancies in Medicare expenditures cannot be easily rectified by rewarding the more cost-efficient regions. For one thing, cost variation among providers, within a region, is large, which makes it hard to apply incentives on a regional basis.

The Puzzling Return of Glass-Steagall

I am puzzled by the renewed demand for the return of Glass-Steagall. I am puzzled not because Glass-Steagall might be bad policy but because it is so clearly a policy that doesn’t deal with the problems that created the financial crisis. If one had to sum the crisis up in one sentence it would be hard to do better than “a run on the shadow banking system.” The shadow banking system is that collection of mostly non-bank financial intermediaries who base their credit creation not on deposits but on repo, money market funds, SIVs, asset backed securitizations and other financial structures. The big new fact that I learned from the financial crisis and that I thought someone like Elizabeth Warren would surely also have learned is that the shadow banking system is larger than the regular banking system.

Separate commercial and investment banking? Please. The problem was that investment banking, in the form of shadow banking, become so separated from commercial banking that the Fed no longer had any idea where a majority of credit was being generated. Credit creation separated from banking as understood by the Fed, and moved into the shadows, hence, the term shadow banking.

Compare Glass-Steagall with the Gorton-Metrick proposal to reform banking. GM would in essence extend deposit insurance to the shadow bank system, i.e. instead of separating commercial and investment banking, Gorton and Metrick would erase the distinction entirely by making all credit creators regulated commercial banks. (I exaggerate, but only slightly). If you don’t like that idea then consider Larry Kotlikoff’s limited purpose banking. Kotlikoff, in essence, goes the full Rothbard–separate lending from money warehousing (i.e. transaction-cost reducing money services) (Tyler offers some criticisms here).

Now whether you think the Gorton-Metrick or Kotlikoff proposals are good ideas, and I am not arguing for either, these ideas at least addresses the important issues. In contrast, Glass-Steagall would merely shuffle around organizational boxes in the less important regulated banking sector. Indeed, why would anyone think that 1930s policy is the solution to a 21st century problem?

Addendum: Here are previous MR posts on Glass-Steagall. FYI, my paper on the public choice aspects of Glass-Steagall showed that the public reasons for the original Glass-Steagall were not the private reasons. Is something like this going on today?

Will Congress exempt itself from ACA exchange provisions?

Congressional leaders in both parties are engaged in high-level, confidential talks about exempting lawmakers and Capitol Hill aides from the insurance exchanges they are mandated to join as part of President Barack Obama’s health care overhaul, sources in both parties said…

There is concern in some quarters that the provision requiring lawmakers and staffers to join the exchanges, if it isn’t revised, could lead to a “brain drain” on Capitol Hill, as several sources close to the talks put it.

The problem stems from whether members and aides set to enter the exchanges would have their health insurance premiums subsidized by their employer — in this case, the federal government. If not, aides and lawmakers in both parties fear that staffers — especially low-paid junior aides — could be hit with thousands of dollars in new health care costs, prompting them to seek jobs elsewhere. Older, more senior staffers could also retire or jump to the private sector rather than face a big financial penalty.

Plus, lawmakers — especially those with long careers in public service and smaller bank accounts — are also concerned about the hit to their own wallets.

Here is more, via these guys.

Addendum: Here is a response from Ezra Klein to the Politico story, but I don’t see that it counters the basic point, as reflected by this brouhaha, that the exchanges are not necessarily such a wonderful place to be, especially for low wage workers. Megan McArdle also comments.

Trade vs. technology, in terms of their labor market effects

Here is the new paper by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson, “Untangling Trade and Technology: Evidence from Local Labor Markets”:

We analyze in a common framework the differential effects of trade and technology on employment patterns in U.S. local labor markets between 1990 and 2007. Labor markets whose initial industry composition exposes them to rising import competition from China have experienced significant employment reductions particularly in the manufacturing sector and among non-college-educated workers. These employment losses are not limited to manual production jobs but also affect clerical and managerial occupations. Labor markets that are susceptible to computerization due to specialization in routine task-intensive activities have neither experienced an overall decline in employment, nor a differential change in manufacturing employment. However, the occupational structure of employment of these labor markets has polarized within each sector, as employment shifted from routine clerical and production occupations to more highly skilled managerial or professional occupations, as well as to lower skilled manual and service occupations. While the effect of trade competition is growing over time due to accelerating import growth, the effect of technology seems to have shifted from automation of production activities in the manufacturing sector towards computerization of information-processing tasks in the service sector.

Australian Travel Notes from a Policy Wonk

Here are some notes on Australia, mostly from and for policy wonks.

Australia has a private pension system. In the 1990s a Labor government, with the support of the trade unions, created a system of private pension accounts to supplement the basic, means-tested state pensions that Australia has had since 1909. Employers are required to pay 9% of an employee’s wages (scheduled to increase to 12%) into the private accounts. The funds can be withdrawn at retirement (age 60 for new workers), at age 65, or in exceptional cases with disability. Workers can invest their funds with very few restrictions–workers, for example, can choose among a variety of mutual funds (such as Vanguard etc.) or invest with non-profit funds run by trade union associations or they can even self-manage. The accounts, now totaling more than 1.4 trillion, have increased savings and made Australia a shareholder society. Some issues remain including fees which are probably too high (better default rules could help) and a lack of annuitization (annuitization of some portion of the lump sum payment should be required to avoid moral hazard)–see here for one critique–but overall the system appears very favorable relative to the American system.

Australia farmers pay for water at market prices. Water rights are traded and government water suppliers have either been privatized or put on a more stand-alone basis so that subsidies are minimized or at least made transparent.

Australia has one of the largest private school sectors in the developed world with some 40% of students in privately-run schools.

Australia has a balanced-budget principle (balanced over the business cycle) which has been effective although perhaps more important has been a widely held aversion to deficits combined with an understanding of sustainability and intergenerational fairness (factors which also played a role in the decision to create private, pre-funded pensions).

Prostitution is legal in much of Australia and some of Sydney’s brothels have made significant capital investments.

The Australian civil service is of very high quality. I spoke at the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Treasury and the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (whew) and in all cases I found the civil servants to be highly informed and sophisticated. I was not the first to bring up the term rent seeking or to laugh at the latest political shenanigans which everyone acknowledged had been done for votes and not for sound reasons of public policy. All consistent with Yes, Minister but it gave me a different perspective.

More than a quarter of the Australian population is foreign born but there is very little cultural or economic tension about immigrants within Australia (with minor exceptions over refugees (“jumping the queue”) and occasional minor flare-ups over job visas). From cab drivers to MPs the word on immigration was, “Not an issue, mate.”

I had some of the best Thai food I have ever had anywhere. Spice I Am was excellent (thanks!) and Home on Sussex was outstanding.

The Manly ferry is a great way to see Sydney’s magnificent coastline.

The world owes Sydney barristas (New Zealand also) an enormous debt for the flat white, perhaps the best form of coffee yet perfected. The flat white has made its way to London but is only now becoming available in a few high end coffee shops in New York. I eagerly await for this trend to extend to Fairfax as I am already jonesing for another.

Australia has great natural beauty. The British should have left the convicts behind and moved everyone else.

Addendum: And here is Lars Christensen on Australian monetary policy, also very good, and Reihan Salam with more on education.

The economics of budget sequestration

Here is my latest New York Times column, on how we should deal with sequestration. One theme is that, economically speaking, we really can get away with cutting our defense budget:

In the short run, lower military spending would lower gross domestic product, because the workers and resources in those areas wouldn’t be immediately re-employed. Still, that wouldn’t mean lower living standards for ordinary Americans, because most military spending does not provide us with direct private consumption.

To be sure, lower military spending might bring future problems, like an erosion of the nation’s long-term global influence. But then we are back to standard foreign policy questions about how much to spend on the military — and the Keynesian argument is effectively off the table.

On a practical note, the military cuts would have to be defined relative to a baseline, which already specifies spending increases. So the “cuts” in the sequestration would still lead to higher nominal military spending and roughly flat inflation-adjusted spending across the next 10 years. That is hardly unilateral disarmament, given that the United States accounts for about half of global military spending. And in a time when some belt-tightening will undoubtedly be required, that seems a manageable degree of restraint.

When you hear talk of Keynesian arguments as applied to sequestration, don’t be so quick to aggregate the “G.” The Keynesian argument, as well as some supply-side arguments, does apply however to infrastructure and also to the funding of basic scientific research. The domestic half of the sequester should be redone to focus more tightly on farm subsidies and Medicare reimbursement rates:

THE Keynesian argument suggests that spending cuts do the least harm in economic sectors where demand is high relative to supply. Thus, the obvious candidate for the domestic economy is health care, and the sequestration would cut many Medicare reimbursement rates by 2 percent. We could go ahead with those cuts or even deepen them, because America has had significant health care cost inflation for decades.

We already have huge demand in our health care system, along with a corresponding shortage of doctors. And the coverage extension in the Affordable Care Act will add to the strain. In this setting, cutting Medicare reimbursement rates wouldn’t result in fewer health care services over all. Yes, doctors might be less keen to serve Medicare patients but might be more available for others, including the poor and the young. In the long run, the improved access for those groups would yield much return on investment, and would move the health care system closer to many of the European models.

Of course that is unlikely to happen. Here are some related points by Veronique de Rugy, which I found helpful for doing the piece.

I would view the sequestration as a kind of referendum on whether we are ever capable of cutting or restraining spending and I fear not. When it comes to the defense budget, “gdp fetishism” suddenly makes a comeback. Or sometimes I read or hear the argument: “let’s not do this, it is only a small nick in the budget deficit.” That attitude is exactly the problem. The point remains that the laws of opportunity cost still apply. As David Brooks has noted, I am willing to live with the price of my house going down.

A few points about the British growth slowdown

1. The BBC reports: “The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said the fall in output was largely due to a drop in mining and quarrying, after maintenance delays at the UK’s largest North Sea oil field.”

2. According to an FT account, output in the construction sector has fallen eleven percent over the last year.

3. Taking away those two problems, growth was about 0.7 percent, and 1.4 percent in the service sectors. The service sectors represent about four-fifths of the economy.

4. Their relative shares in export markets are generally falling.

You can debate how much those numbers fit the pattern of an AD shortfall (I don’t see it myself, though there is room to make some of a case on the construction side), but what is remarkable is how many people don’t even want to raise these issues.

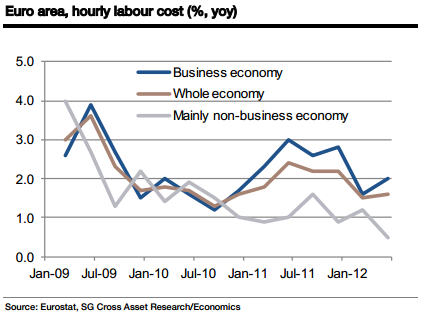

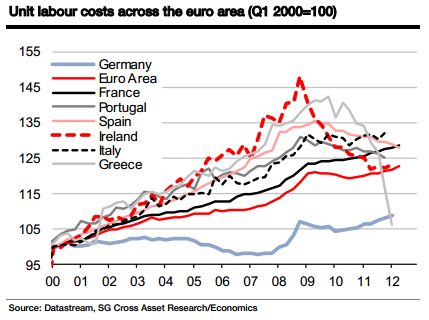

Eurozone sticky wage update

From the always essential FT Alphaville:

Société Générale points out that unit labour costs — basically, wages — have been falling quite rapidly in the peripherals, and that this is probably due to austerity measures. New data from Eurostat breaks out what the agency calls ‘non-business’ wages: the education, health services, and public administration sectors. In otherwords, ‘non-business’ is a rough proxy for the public sector:

The logical follow-on from the above being that “non-business” sectors are a big contributor to the rapidly falling unit labour costs in the periphery, especially given their large state sectors:

SocGen’s Michel Martinez writes that there are outright wage declines in Greece while in the other peripherals, labour productivity (as measured by ULC) is outpacing wage gains.

TC again: No one should doubt that depreciation and expansionary monetary policy are a much easier path to lower real wages. Yet the claim that wages are outright sticky for long periods of time, when economic pressures dictate wage declines, isn’t holding up that well.

And I would add this: They are not as wealthy as they thought they were.

Have the French shown that water privatization is dead?

Some time ago, @ModeledBehavior has requested comment on this article. Excerpt:

Across the nation cash-strapped municipalities are considering the sale of their public-utility systems. These moves are intended to raise cash and rid the municipalities of expensive liabilities such as debt service and pension obligations. But officials considering this approach might do well to look to France and other nations that are rapidly moving in the opposite direction with a “remunicipalization” of their utility systems. In 2010, Paris, in the best known case of remunicipalization, ended contracts with the world’s two biggest water service companies, Suez and Veolia, bringing an end to their 100-year private duopoly. The reversal of a century-old practice in Paris was an acceleration of an international movement away from private control.

So what’s up? I see it this way. For advanced water systems, there is no cost advantage to having a privatized system. It is a regulated monopoly and over time it acquires skill in manipulating the political process, most of all its regulators. Why expect lower costs and prices? A wide variety of studies of this topic, including studies by “market-oriented” economists, find no cost advantage for the private sector in this setting.

For very poor countries, very often water privatization would in principle be a good idea, since the public sector is not supplying much piped water at all. Monopoly is better than carrying a bucket on your head, and you still can carry the bucket if you wish. Yet privatization also won’t get very far in many of these cases. One reason is that there is no way to make people — many of whom are non-registered and lacking in assets — pay their water bills, and not enough legal infrastructure to prevent them from cutting into the pipes or otherwise going rogue. You shouldn’t “blame” privatization here, but still it may not be a useful option.

Finally, there is a sweet spot in the middle, often for reforming or middle-income countries. In those cases water privatization can mobilize private capital rapidly and expand water coverage. It often brings higher quality water, higher quality connections, lower rates of unaccounted-for-water, and higher prices. Not all cities desire that trade-off, but it is there for the taking. Some of these privatizations are done fairly well, others are done very poorly, such as in Cochabamba, where the “privatization” gave the company property rights over previously privately held, decentralized water sources of the poor, such as collected rain.

As long as there are countries in this middle income range, water privatization is not dead nor should it be.

Why is American labor mobility falling?

The first [reason] is that the mix of jobs offered in different parts of America has become more uniform. The authors compute an index of occupational segregation, which compares the composition of employment in individual places with the national profile. Over time, their figures show, employment in individual markets has come to resemble more closely that in the nation as a whole.

This homogenisation reflects the rising importance of “non-tradable” work…

Yet a more uniform job distribution alone cannot account for falling mobility. As Messrs Kaplan and Schulhofer-Wohl point out, mobility has fallen for manufacturers, where jobs are more dispersed, as well as for service-sector workers. What is more, if workers know that they can find jobs they want in different places, they may become more willing to move for other reasons—to be by the coast, for example, or to savour a particular music scene. Yet survey data reveal that moves for these other reasons have not risen. The authors suggest another force is also reducing migration: the plummeting cost of information.

…In recent decades, however, it has become much easier to learn about places without moving house. Deregulated airlines and innovative online-travel services have slashed travel costs, allowing people to visit and assess different markets without moving. The web makes it vastly easier to study every aspect of a potential new home, from the quality of its apartment stock to the surliness of its baristas, all without leaving home. Falling mobility isn’t simply caused by labour-market homogenisation, the authors argue, but also by greater efficiency. People are able to find the right job in the ideal city in fewer hops than before.