Results for “service sector” 459 found

The Great (Male) Stagnation

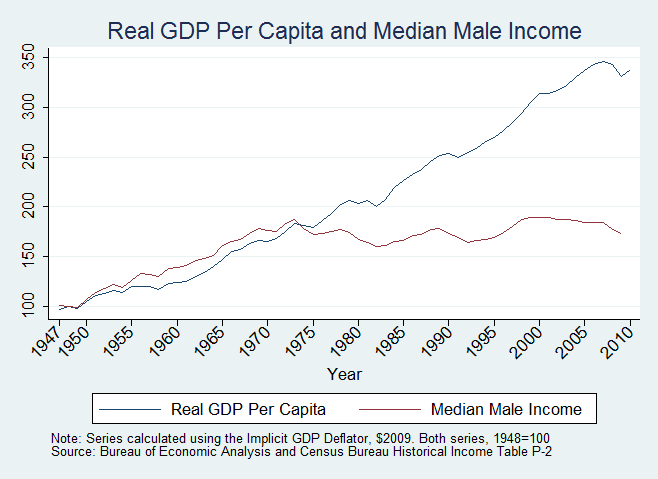

You have probably seen something like the following graph which shows real GDP per capita and median male income since 1947. Typically, the graph is shown with family or household income but to avoid family-size effects I use male income. It’s evident that real gdp per capita and median male income became disconnected in the early 1970s. Why? Explanations include rising inequality (mean male income does track real gdp per capita somewhat more closely), Tyler speculates that the nature of technological advances has changed, other people have speculated about rising corporate profits. Definitive answers are hard to come by.

Here is another set of data that most people have not incorporated into their analysis:

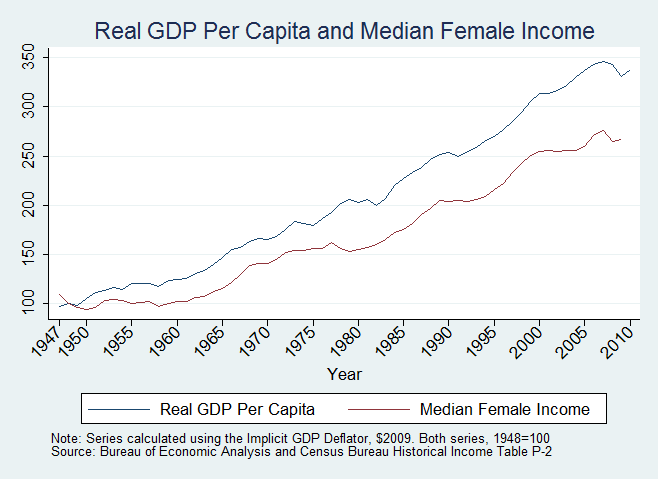

Median female income tracks real GDP per capita much more closely than does median male income. It’s unclear which, if any, of the above explanations are consistent with this finding. Increasing inequality, for example, predicts an increasing divergence in real GDP per capita and female median income but we don’t see this in the graph (there is a slight increase in the absolute difference but the ratios don’t increase). Similarly, we would expect changes in technology and corporate profits to affect both male and female median income equally but in fact the trends are very different.

One can, of course, do the Ptolemaic move and add an epicycle for differences in male and female inequality and so forth. Not necessarily wrong but not that satisfying either.

The big difference between female and males as far as jobs, of course, has been labor force participation rates, increasing strongly for the former and decreasing somewhat for the latter. Most of the female change, however, was over by the mid to late 1980s, and the (structural) male change has been gradual. Other differences are that female education levels have increased dramatically and male levels have been relatively flat. Females are also more predominant in services and males in manufacturing: plumbers, car mechanics, carpenters, construction workers, electricians, and firefighters, for example are still 95%+ male. Putting these together points to a skills and sectoral story, probably amplified by follow-on changes in labor force participation rates.

Thinking about the story this way also reminds us that the median male or female is not a person but a place in a distribution. The median male in 1970 can get rich by 1990 even though median male income is flat.

Again, no definitive answers, but the raw patterns are striking.

Note: An extra high tip of the hat to Scott Winship who whipped up all of the data during a discussion.

The offshore bias in U.S. manufacturing

In the newest Journal of Economic Perspectives, Susan Houseman, Christopher Kurz, Paul Lengermann and Benjamin Mandel report:

In this paper, we show that the substitution of imported for domestically produced goods and services—often known as offshoring—can lead to overestimates of U.S. productivity growth and value added. We explore how the measurement of productivity and value added in manufacturing has been affected by the dramatic rise in imports of manufactured goods, which more than doubled from 1997 to 2007. We argue that, analogous to the widely discussed problem of outlet substitution bias in the literature on the Consumer Price Index, the price declines associated with the shift to low-cost foreign suppliers are generally not captured in existing price indexes. Just as the CPI fails to capture fully the lower prices for consumers due to the entry and expansion of big-box retailers like Wal-Mart, import price indexes and the intermediate input price indexes based on them do not capture the price drops associated with a shift to new low-cost suppliers in China and other developing countries. As a result, the real growth of imported inputs has been understated. And if input growth is understated, it follows that the growth in multifactor productivity and real value added in the manufacturing sector have been overstated. We estimate that average annual multifactor productivity growth in manufacturing was overstated by 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points and real value added growth by 0.2 to 0.5 percentage points from 1997 to 2007. Moreover, this bias may have accounted for a fifth to a half of the growth in real value added in manufacturing output excluding the computer and electronics industry.

In other words, Michael Mandel was right. An ungated version is here. In terms of income distribution, think of these rents as going to those individuals and institutions which are good at managing international supply chains. That’s a relatively small number of people. A lot of the offshoring is enabled by an innovation — the internet — which really does boost productivity but not in a way which much helps the median U.S. wage.

How much productivity growth was there during 2007-2009?

Michael Mandel has a long and excellent blog post on this question. He claims that the supposed productivity gains were concentrated in a small number of sectors (one of which, by the way, was financial services ha-ha) and that they are mostly illusory when cross-checked with other sources of data. Here is his final conclusion:

However, the effect of the adjustment on the 2007-2009 period is spectacular. Productivity growth, which had been 1.6% annually in the original data, basically disappears. The decline in real GDP is twice as large (-1.3% per year in the original data, -2.9% in the adjusted data). And economists are no longer presented with the confounding puzzle of why unemployment rose so much with such a modest decrease in GDP–it’s because the decrease in GDP was not so modest. (see a piece here on Okun’s Law, which links GDP changes with unemployment changes).

His redone figures, by the way, are based on the assumption that intermediate inputs are growing and shrinking roughly at the rate of final product (Mandel believes we are mismeasuring these intermediate inputs and thus finding illusory productivity gains over that period.) Think of his alternative numbers as illustrative rather than necessarily his best estimate. The implications of his analysis include:

1. Productivity statistics aren’t well set up to cover outsourcing.

2. Beware of measured productivity gains, reaped over short periods of time, based on supposed drastic declines in intermediate inputs. We’re probably mismeasuring those inputs. Mike’s examples on these points are pretty convincing, walk through what he does for instance take a look at his numbers on mining: “Mining, for example, combines a 10% drop in real gross output with an apparent 46% drop in real intermediate inputs, leading to a reported 23% gain in real value-added and a 26% gain in productivity. It’s very hard to understand how intermediate inputs decline four times as fast as output!”

3. During the crisis, output fell more than we thought and thus our recovery isn’t going as well as we think. (By the way, this is the most effective critique of the ZMP hypothesis, since the implied decline in true output now comes much closer to matching the measured decline of employment.)

4. Issues of “international competitiveness” are much more important than either economists or the Obama administration have been thinking. Excerpt:

…the mismeasurement problem obscures the growing globalization of the U.S. economy, which may in fact be the key trend over the past ten years. Policymakers look at strong productivity growth, and think they are seeing a positive indicator about the domestic economy. In fact, the mismeasurement problem means that the reported strong productivity growth includes some combination of domestic productivity growth, productivity growth at foreign suppliers, and productivity growth ”in the supply chain’. That is, if U.S. companies were able to intensify the efficiency of their offshoring during the crisis, that would show up as a gain in domestic productivity.

5. Read #4 directly above, think about who captures those gains, and you can see that the Mandel productivity hypothesis is broadly consistent with some of the data on income inequality.

6. There really is a structural unemployment problem and it stems from ongoing low productivity growth.

7. At the risk of sounding self-congratulatory, if you combine Mike’s estimates with the new Spence paper, and the reestimation for male median wages (down 28 percent since 1969), in my view the TGS thesis is looking stronger than it did even two months ago when the book was published.

*Inside Job*

Nick writes to me:

I'm an undergrad math/Econ double major and aspiring economist. I also read your blog (amongst others) daily. You said today that "Inside Job" was "half very good and half terrible." Critical reviews are widespread, but prominent economists haven't said much. I was wondering if you could expound on your terse critique in an email or blog post.

It's been a while since I've seen the movie, but here goes. The best parts are on excess leverage, the political economy of the crisis, and the attitudes of the economics profession. Overall it is remarkable how much economics is in the movie, even though some of it is quite bad. The visuals and pacing are excellent and many scenes deserve kudos.

The worst parts are the misunderstandings of deregulation. Glass-Steagall repeal was not a major factor, much of the sector remained highly regulated, and there is no mention of the failure to oversee the shadow banking system. The entire discussion has more misses than hits. The smirky association of major bankers with expensive NYC prostitutes (on one hand based on very little evidence, on the other hand probably true) was inexcusable. There is talk of "predatory lending," but it is not mentioned that many borrowers committed felonies, or were complicit in felonies ("on the form, put down any income you would like"). Most generally, there is virtually no understanding of the complexity of the dilemmas involving in either public service or in running a major corporation.

Overall, the movie's smug moralizing makes me wonder: is this a condescending posture, spooned out with contempt to an audience regarded, one way or another, as inferior and undeserving of better? Or are the moviemakers actually so juvenile and/or so ignorant of the Western tradition — from Thucydides to Montaigne to Pascal to Shakespeare to Ibsen to FILL IN THE BLANK — that they themselves accept the very same simplistic moral portrait? If so, most of all I feel sorry for how much of life's complexities they are missing and how impoverished their reading and moviegoing and theatregoing must be.

Do you remember the scene in Hamlet, where Hamlet tries to judge the King by enacting a pantomime play in front of him, to see how the King would respond to a work of art? I think of that often.

Have the rich caused middle class wage stagnation?

I don't always agree with Kevin Drum, but usually I find that he has good arguments. In this passage, however, I think he is overreaching:

Still, I don't think that a plausible story of causation [the gains of the wealthy to the stagnation of other incomes] is really all that hard. First, take a look at middle class income stagnation. What caused that? Matt already pointed to one cause: monetary policy since the late 70s that's kept inflation low at the cost of keeping labor markets persistently loose. To that, I'd add several other trends that have marked the past three decades: trade policies that accelerated the decline of U.S. manufacturing; domestic deregulation policies that squeezed workers; stagnation in the minimum wage; immigration policies that reduced wages at the low end; and a 30-year war against labor that devastated unions and reduced the bargaining power of the working class.

First, money matters in the short-run most of all. Tight money (unless maybe it is radical deflation, but even then the U.S. resumed growth out of the GD fairly quickly and furthermore the median worker was not unemployed) is not a plausible cause of median income stagnation over decades. The link between trade and wage stagnation does not find support in the data. Deregulation hurt the wages of air traffic controllers, but how many other groups? Enough to shift the median? Stagnation in the real minimum wage shouldn't much hurt median wage growth over a forty year period. Unions fell mostly because of the shift to services, and furthermore the "union wage premium" in the data is a one-time ten to fifteen percent gap, not an ongoing change in rates over decades, and it is reaped by some not all workers.

In my view the gains of the top one percent and the stagnation at the median are largely separate phenomena; note that the top gains so dramatically only in the Anglosphere, whereas growth stagnation affects most of the OECD after the early 1970s.

How then might rent-seeking in the top income brackets damage ordinary Americans, as I have myself suggested? The most plausible mechanism is this: gains of the wealthy through capital markets come at the expense of other individuals in capital markets. Some kinds of capital — for instance finance capital – had been profiting more and implicitly taxing other kinds of capital, often through "trading," broadly not narrowly construed. The taxed capital "retreats" and this has adverse affects on labor, much as an increase in the corporate income tax falls partially on labor and partially on consumers (which also shows up as lower real wages).

The labor which is "subsidized" by this change in capital returns is smaller in number and more concentrated, sectorally, than the labor which is taxed.

I wouldn't say there is massively firm evidence for this hypothesis, but rather it is the major contender by process of elimination. If you are wondering, many of the years of wage stagnation have shown relatively low shares of investment in gdp; see the new McKinsey report "Farewell to cheap capital?".

So there we have one factor connecting the gains at the top to losses at the median but still I do not think it is the major factor behind median stagnation. I will be writing more on this.

Does the UK have the best health care institutions in the world?

Not in the present day time slice sense ("did he write "best," didn't he mean "worst"?"), but think of it over time. There is a big lock-in effect. The United States, for instance, cannot easily switch into another way of organizing its health care system. Obamacare is built upon current institutions and, for better or worse, does more to lock them in than to modify them.

Let's say you think an optimal mix is government-run clinics for the poor and reliance on the market for wealthier individuals, with people in the middle using some mix of the two. The government clinics enact redistribution at relatively low cost and this means you don't have to overly regulate the private market. People can take their chances with the market, or fall back on the cheaper but possibly inferior government service. Think of it as a public option at the level of provision rather than insurance.

Now that is not exactly the current regime in the United Kingdom. For one thing, the public sector is too large and the private alternatives are both too small and not free enough. But could you not imagine their institutions evolving into some version of this, mostly through growth of a less-regulated market sector?

Can you imagine the same evolution for the American system?

Addendum: Ezra discusses how the American system might evolve. And Austin Frakt comments.

Ireland facts of the day

The increase in spending, which is part of Ireland’s present problem, is quite recent. From 2000 to 2006, the number of people employed in the Irish health sector increased 20 percent, in education by 27 percent, in the justice sector by 22 percent, and in the civil service by 27 percent.

In the past decade, Irish health spending has doubled, in real terms. In 2000, about 22 million items were prescribed; 10 years later, 52 million items were. People aren’t twice as healthy as a result.

As far as taxes on income are concerned, Irish people now pay about half as much as an equivalent family does on the same income in Germany. There is currently no recurring tax on property, no charge for water supplies, and modest fees for a college education. Welfare payments compare favorably with those in Northern Ireland.

Here is more. Currently there is talk of a "buyer's strike" in the market for Irish bonds. When the Irish accept the full extent of the standard of living "reset" implied in all of this, how big a step back will be required? Ten years? More? If you take away pre-war, war, and post-war examples, is there any precedent for such a large reset in the history of wealthy countries? Apart from contemporary Iceland, that is.

Structural Unemployment in South Africa

Unemployment in South Africa is now running at 24% overall with significantly higher rates for blacks. A shift away from low-skill labor combined with minimum wages and strong trade unions, however, has meant that it is very difficult to lower wages and reduce unemployment. From a very good piece in the NYTimes:

The sheriff arrived at the factory here to shut it down, part of a national enforcement drive against clothing manufacturers who violate the minimum wage. But women working on the factory floor – the supposed beneficiaries of the crackdown – clambered atop cutting tables and ironing boards to raise anguished cries against it…

Further complicating matters, just as poorly educated blacks surged into the labor force, the economy was shifting to more skills-intensive sectors like retail and financial services, while agriculture and mining, which had historically offered opportunities for common laborers, were in decline.

The country’s leaders invested heavily in schools, hoping the next generation would overcome the country’s racist legacy, but the failures of the post-apartheid education system have left many poor blacks unable to compete in an economy where accountants, engineers and managers are in high demand….

Last year, as South Africa’s economy contracted amid the global

financial crisis, unions negotiated wage increases that averaged 9.3

percent [inflation is 5.1%, AT]….Eight months ago, Mr. Zuma proposed a wage subsidy

to encourage the hiring of young, inexperienced workers. But it ran

into vociferous opposition from Cosatu, the two-million-member trade

union federation that is part of the governing alliance [insiders v. outsiders, AT], which

contended that it would displace established workers.

Hat tip: Brandon Fuller.

*Winner-Take-All Politics*, the new book by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson

That's the new book by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson. I have a different take on the main argument, but this is an important book for raising some of the key questions of our time. I would recommend that people read it and give it serious thought. The writing style is also clear and accessible. Two of the key arguments are:

1. Skill-based technological change is overrated as a cause of growing income inequality among the top earners.

2. "The guilty party is American politics."

You'll find an article-length version of some of the Hacker-Pierson argument here, although the book covers much more.

I agree with #1, so let me explain why my take on #2 differs:

1. Median income starts stagnating in 1973 and income inequality starts exploding in 1984, according to the authors. However, I consider this a "long" time gap for the question under consideration, namely whether there is a direct causal relation and whether people at the top are using politics to skim from people further below in the income distribution. Furthermore income growth stagnates around 1973 for many countries, not just the United States, and most of those countries never experienced the subsequent "inequality boom" of the Anglosphere. If they avoided the later inequality, why didn't they also avoid the stagnation? The discussion of the causal issues here isn't convincing and the authors' hypothesis is not compared to alternatives or tested against possible disconfirming evidence.

2. There is a lot of talk of unions, but I could concede various points and that's still just a ten to fifteen percent one-time wage premium, when workers are unionized. It won't much explain persistent changes in growth rates over time, whether for the top one percent or the slow income growth at the median. Furthermore the main U.S. sectors are harder to usefully unionize than, say, Canada's mineral and resource wealth or Europe's manufacturing.

3. The authors underestimate the role of finance in driving the growth in income inequality. Their p.46 shows a graph suggesting that non-financial professionals are 40.8% of the top 0.1 percent. Maybe so, but the key question is what percentage of income those professionals account for. The Kaplan and Rauh paper, not cited in this book, suggests a central role for finance. In 2007 the top 5 hedge fund earners pulled in more income than all the CEOs of the S&P 500 put together. On top of that, some "non-financial" incomes are driven by financial market trading, such as in energy or commodity companies. And a lot of top-earning lawyers are doing financial deals, etc.

Turn to Table 7 of the paper cited by the authors, p.56 here. The "non-financial" category still looks bigger but it's incomes in the finance category which grow most rapidly and Bakija and Heim suggest that stock options and asset price movements account for a big share of the growth in "non-financial" incomes. My view is that the increasing liquidity of financial markets drove much of the trend, which was distributed across both the "non-financial" and the "financial" sector. If liquid financial markets allow a privately-owned warehouse company to buy a trucking company on the cheap, and profit greatly (plus the managers pull in a lot), I am calling that a financial markets development, even though it's in the "non-financial" sector.

4. Let's say the story at the top is mostly one of finance. You could describe that as: "some change in financial markets led to rapid income growth for the top earners and politics did nothing about that." Fair enough. But it's still a big leap from that claim to portraying politics as the active force behind the change. Politics was only the allowing force and I don't think there was much of a conspiracy, even if various wealthy figures did push for deregulation or more importantly an absence of new regulation. I also don't think anybody was expecting incomes at the top to rise at the rates they did; it was a kind of pleasant surprise for the top earners to be so lucratively rewarded. So the major change is left unexplained, for the most part, and the whole story is then shifted onto the passive actor, namely the public sector, which is elevated to a major causal role which it does not deserve.

5. pp.47-51 the authors talk about tax rates. If we had kept earlier high marginal rates, the top earners would not have received nearly so much and also they would not have worked so hard. Maybe so, yet this won't much explain the stagnating pre-tax incomes at the median and it doesn't fit very well into the overall story, unless you wish to make a complicated "lower tax revenue, lower quality public services, MP of the median earner goes down" sort of story.

6. If the top earners are screwing over their wage earners in the big companies, by pulling in excess wages, options, and perks, we should observe non-stagnant median pay for people who avoid working in firms with fat cat CEOs. Or we should observe talented lower-tier workers fleeing the big corporations, to keep their wages up. Yet no evidence for these predictions is given, nor are the predictions considered. It is likely that the predictions are false.

7. To the extent the high incomes at the top come through capital markets, it is either value created or a transfer/redistribution. You can argue over the percentages, but to the extent it is the former it is not at the expense of the median. To the extent it is the latter, the losers will be other investors, not the median earner or household, who does not hold much in the way of stock (lower pension fund returns don't count in the measure of median stagnation).

8. What follows p.72 is an engaging, readable progressive history of recent American politics, but the economic foundations of the underlying story have not been pinned down.

9. In my view, most likely we have two largely separate phenomena: a) median wage growth slows in 1973 because technology stagnates in some regards, and b) liquid financial markets, in various detailed ways, allow people with resources to earn a lot more than before. Politics may well play a role in each development, but with respect to b) its role has been largely passively, rather than architectural and driving.

Anyway, I found it a very useful book for organizing my thoughts on these topics.

Addendum: Matt Yglesias comments.

What’s holding back small business?

Catherine Rampell has a very useful graph, displayed here, and cited favorably by Krugman and also deLong. Karl Smith correlates sales complaints with high unemployment and complains about Arnold Kling.

Krugman wrote, for instance, "Businesses aren’t hiring because of poor sales, period, end of story".

I didn't read this graph the same way. I saw poor sales as a "biggest problem" for fifteen percent (or so) of small businesses in periods of full or near-full employment. I also see "poor sales" as a "biggest problem" for about thirty percent of small businesses today. That change — about fifteen percent of the total — struck me as relatively small and indeed puzzlingly small, if indeed we are in a liquidity trap and weak AD is the overwhelmingly dominant problem. (In fact I might expect an Austrian to cite such a number in support of their story.) I do think weak AD is an important problem to be addressed, I just don't think the absolute levels here imply "end of story." I look at that graph and think "this is a multi-factor problem."

I also note that larger businesses have fairly high levels of profit right now and that the pattern of unemployment — lots of permanance, and among the less educated — is not obviously correlated with where we would expect to find either most nominal wage stickiness or the greatest lack of spending.

I note as well that the most plausible sectoral shift stories also imply that businesses will complain about poor sales. Furthermore, many of the synthetic RBC-neo-Keynesian models — which long ago displaced the simple MC-driven RBC models of the early 80s — are consistent with these data as well.

A lot of the correlations in the diagram don't quite make sense, such as "inflation" becoming a much more serious problem in 2007, or how "insurance cost" changes. And might such a diagram ever imply that we should lower taxes on business? Russ Roberts comments:

In fact, if there had been one category called “Taxes and Government Regulations” it might have been seen as the biggest problem, listed by 36% of respondents, up from 29% in the year before and surpassing sales as the biggest problem.

One key question is how to get sustainably higher sales, most of all for wealth-elastic and income-elastic and credit-elastic goods and services. This diagram doesn't tell me how to fix that problem or where that problem comes from, but that is a critical issue, maybe the critical issue.

Overall, I look at that chart and I think the jury is still out, to say the least.

My debate with Bryan Caplan on education

Bryan writes:

The other day, Tyler Cowen challenged me to name any country that I consider under-educated. None came to mind. While there may be a country on earth where government doesn't on net subsidize education, I don't know of any.

…This analysis holds in the Third World as well as the First. The fact that Nigerians and Bolivians don't spend more of their hard-earned money on education is a solid free-market reason to conclude that additional education would be a waste of their money.

I would first note that many parts of many poor countries, today, receive de facto zero government subsidies for education. Or put aside the issue of government provision and ask if you were a missionary and could inculcate a few norms what would they be? Many regions – in particular Latin America — are undereducated for their levels of per capita income. I view this as a serious cultural failing, most of all in terms of its collective social impact. In contrast, Kerala, India is very intensely educated for its income level and that brings some well-known benefits in terms of social indicators and quality of life.

If I think of the Mexican village where I have done field work, the education sector "works" as follows. No one in the village is capable of teaching writing, reading, and arithmetic. A paid outsider is supposed to man the school, but very often that person never appears, even though he continues to be paid. Children do have enough leisure time to take in schooling, when it is available. I am told that most of the teachers are bad, when they do appear. You can get your children (somewhat) educated by leaving the village altogether, and of course some people do this. In the last ten years, satellite television suddenly has become the major educator in the village, helping the villagers learn Spanish (Nahuatl is the indigenous language), history, world affairs, some science from nature shows, and telenovela customs. The villagers seem eager to learn, now that it is possible.

That scenario is only one data point but it is very different than the "demonstrated preference" model which Bryan is suggesting. Bolivia and Nigeria are much poorer countries yet and they have dysfunctional educational sectors as well, especially in rural areas. Bad roads are a major problem for "school choice" in these regions, just as they are a major problem for the importation of teachers.

A simple model is that underinvestment in infrastructure results in a high shadow value for marginal increments of education. Model = high fixed costs, liquidity constraints if you wish, high shadow values for lots of goods and services, toss in social externalities to raise the size of the distortion. I read Bryan as focusing on "the fixity of the fixed costs" and claiming it is too costly to get the service through, relative to return.

Of course Bryan favors rising wealth and falling fixed costs, as do I. But in the meantime he also should admit that a) education "parachuted" in from outside can have a high marginal return, b) collectively stronger pro-education norms raise demand and can alleviate the high fixed costs problem, c) there are big external benefits, some operating through the education channel, to lowering the fixed costs, d) stronger pro-education norms put a region closer to a "big breakthrough" and weaker education norms do the opposite, and e) a-d still impliy "too little education" is the correct judgment. On b), some evangelical groups in Latin America do seem to have stronger pro-education norms in their converts and it appears to be much better for the children of these families and no I'm not going to buy any response which ascribes the whole effect to selection.

I believe that Bryan's own work on voting suggests significant positive social external benefits from education, although he is not happy with how I characterize his view here. I also believe his views on children suggest strong peer effects across children (parental effort doesn't matter so much in his model and the rest of the influence has to come from somewhere), though in conversation I am again not sure he accepts this characterization.

I consider most countries in today's world to be undereducated.

Signaling models are important but they are not the only effect and of course a lot of signaling is welfare-improving for reasons of screening and sorting and character reenforcement. The traditional story of high social returns to education is supported by evidence from a wide variety of different fields and methods, including cross-sectional growth models, labor economics, political science, public opinion research, anthropology, education research, and much more. You can knock some of this down by stressing the endogeneity of education, but at the end of the day the pile of evidence, and the diversity of its directions, is simply too overwhelming.

Would you like more “plain talk” from airline employees?

Robert, a loyal MR reader, writes to me:

Are there any airlines where the flight staff speak/behave more "naturally," as opposed to the robotic beauty queen default? I don't mean this in a snarky way. I'm just curious, since customers don't seem to be overly fond of the default mode, and some folks actively dislike it. I also imagine the enforced pleasantness to be a relatively tough/emotionally costly act for most flight attendants to keep up. However, I am not sure how customers would react to more natural flight-attendant speech, body language etc., given expectations of default behaviour.

My longstanding view is that half of them dislike or sometimes even despise their customers and that their natural speech patterns, given their true feelings, would come across negatively. Perhaps Air Genius Gary Leff can comment on the cross-sectional variations vis-a-vis different airlines. But the problem is a tough one. They face lots of customers, with varying and often unreasonable expectations, and they have few resources to buy them off with.

In which sectors do the service staff have the highest opinions of their customers? (Do you have nominations? How about the old days at Tower Records? How about an indie bookstore?) I would expect a greater extent of plain speak in those situations.

What should we infer about doctors? Ladies of the evening? Economics professors?

Addendum: Gary responds.

Why is there a boom in temporary hiring?

Trevor Frankel offers his thoughts:

The part that most clearly indicates policy is the problem is the temp hiring. If businesses are hiring temps off the bottom of a recession, it means that they're seeing demand pick up but they're too uncertain to actually hire someone full time. This is usually followed by permanent hiring, but in this recovery, it has not been. The only obvious culprits here are a) higher required wages and healthcare costs (minimum wage, housing interventions and Obamacare are prime candidates here) and b) general lack of confidence in the economy and policy (the political climate in general is the prime candidate here).

Here is some background:

Temp hiring has been off the charts – temp jobs are up 20% year over year, while permanent private sector jobs are down 1%. (source: http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2010/08/follow-up-on-temp-services-hiring/)

This is not an argument which I have been pushing, but the boom in temporary hiring does lend some support to it.

Haiti facts of the day

Here's how the public sector is doing:

…one-sixth of its staff died, virtually all its buildings were damaged, and its meagre tax revenues fell by 80%.

Here's how the private sector is doing:

…over 1m people are still packed into 1,300 tent cities in and around the capital. The camps’ population is rising. Haitians who fled to the countryside after the disaster have returned in search of jobs and services. And soaring property prices–inevitable after the ruin of so much of the country’s housing–have put rents beyond the reach of most of the displaced.

That's a heap of bad news, but the part about the growing tent cities is perhaps the worst bit. It means that whatever you read about the tent cities is reflecting the more desirable side of life in Haiti.

Regulation vs. tort

Paul Krugman writes:

Well, here’s the thing: regulation demonstrably does work where tort law doesn’t. Consider the environmental issue: in reality, the perpetrators of oil spills never pay most of the cost; but in reality, environmental regulation has led to much cleaner air and water. (Look up the history of Los Angeles smog or the fate of Lake Erie if you don’t believe me.)

So why does regulation work? If polluters can buy off the system ex post, after a disaster, why don’t they manage to totally corrupt regulation ex ante? There’s a lot to say about that, and I’m sure there’s a literature I haven’t read. But one thing we tend to forget in this age of Reagan is the importance and virtues of a dedicated bureaucracy: when you have professional government agencies with a job to do, and treat them with respect, that job often gets done.

I'll offer a few points:

1. Here is Susan Rose-Ackerman on regulation vs tort (JSTOR). This is a standard piece in the area, and although she does not stress public choice arguments, the upshot is not extremely far from Krugman's conclusions. She thinks that tort can replace regulation to only a limited degree.

2. I agree with Krugman that the "tort only" position espoused by some libertarians does not work. Yet I do not think his remarks are pointing at the best possible understanding of the question. For instance…

3. There is in fact an agency regulating off-shore drilling and in the case under question it totally failed. How can Lake Erie, an orthogonally related success, be cited but this very directly relevant failure not be mentioned?

Furthermore standard accounts of this failure blame regulatory capture, and the Congressional desire for revenue for this failure, not the ideology of free market economics. You might also blame voter sentiment, since Obama seemed to pick up some advocacy of off-shore drilling from the Republicans and arguably this happened because that position proved to be one of the few effective Republican arguments in the last election.

4. There are plenty of problems where tort works better than regulation, most notably when behavior cannot be controlled or measured easily ex ante or where the correct decision relies on the producer's decentralized information. This encompasses numerous areas, from medical practices to accident law to injuries resulting from the handling of guns to, most of all, many micro-components of highly regulated sectors. Here is a legal and moral defense of tort law.

5. Off-shore drilling is closely related to these cases. For a number of obvious reasons, it is hard for the regulator to monitor how safe an off-shore platform really is. We thus rely a lot on ex post penalties in this area (regulatory as well as tort), not because of ideology but because the ex ante proscriptions don't have as much bite as we would like. This reliance on the ex post penalty also means that "regulation plus tort" (never mind "regulation alone" or "tort alone") may not work so well in this area, with or without free market ideology.

6. Krugman seems to argue that regulators are more protected from the ravages of bad ideology than are judges. Maybe yes, maybe no (see below), but such a comparative argument is unnecessary. The most salient point for Krugman's conclusion is simply that optimality requires a bit of regulation and a bit of tort law and that to do without regulation is, in some regards, to be too lax. He could justify his main conclusion much more simply than he does. (That said, I still believe in less regulation than Krugman does, though I accept the logic of this argument.)

7. If we need to make the said comparison – the corruptibility of regulation vs. the corruptibility of tort law – an independent judiciary need not do worse than a respected bureaucracy and indeed the former is arguably more protected from political interference. It's also the case that the judiciary is more likely to overturn very bad behavior from other parts of the government. This is an advantage for judicial approaches over reguatory approaches and it is a further sign of (partial) judicial independence.

8. I worry when numerous bloggers and writers — not just Krugman — hold a primary theory of regulatory failure based on regulators who do not agree with them ideologically. This is at odds with a big chunk of the relevant public choice literature, which stresses knowledge and incentives, yet without ruling out ideological bias as a factor. Political science approaches to regulation offer greater scope for ideological bias as a major cause of regulatory failure, but still it is hardly the dominant theory to the exclusion of others. In this matter we should follow the literature, and evidence, which are there for the taking.