Results for “"first doses first"” 45 found

First Doses First? — show your work!

Alex has been arguing for a “First Doses First” policy, and I find his views persuasive (while agreeing that “halfsies” may be better yet, more on that soon). There are a number of numerical attempts to show the superiority of First Doses First, here is one example of a sketched-out argument, I have linked to a few others in recent days, or see this recent model, or here, here is an NYT survey of the broader debate. The simplest numerical case for the policy is that 2 x 0.8 > 0.95, noting that if you think complications overturn that comparison please show us how. (Addendum: here is now one effort by Joshua Gans).

On Twitter I have been asking people to provide comparable back-of-the-envelope calculations against First Doses First. What is remarkable is that I cannot find a single example of a person who has done so. Not one expert, and at this point I feel that if it happens it will come from an intelligent layperson. Nor does the new FDA statement add anything. As a rational Bayesian, I am (so far) inferring that the numerical, expected value case against First Doses First just isn’t that strong.

Show your work people!

One counter argument is that letting “half-vaccinated” people walk around will induce additional virus mutations. Florian Kramer raises this issue, as do a number of others.

Maybe, but again I wish to see your expected value calculations. And in doing these calculations, keep the following points in mind:

a. It is hard to find vaccines where there is a recommendation of “must give the second dose within 21 days” — are there any?

b. The 21-day (or 28-day) interval between doses was chosen to accelerate the completion of the trial, not because it has magical medical properties.

c. Way back when people were thrilled at the idea of Covid vaccines with possible 60% efficacy, few if any painted that scenario as a nightmare of mutations and otherwise giant monster swarms.

d. You get feedback along the way, including from the UK: “If it turns out that immunity wanes quickly with 1 dose, switch policies!” It is easy enough to apply serological testing to a control group to learn along the way. Yes I know this means egg on the face for public health types and the regulators.

e. Under the status quo, with basically p = 1 we have seen two mutations — the English and the South African — from currently unvaccinated populations. Those mutations are here, and they are likely to overwhelm U.S. health care systems within two months. That not only increases the need for a speedy response, it also indicates the chance of regular mutations from the currently “totally unvaccinated” population is really quite high and the results are really quite dire! If you are so worried about hypothetical mutations from the “half vaccinated” we do need a numerical, expected value calculation comparing it to something we already know has happened and may happen yet again. When doing your comparison, the hurdle you will have to clear here is very high.

When you offer your expected value calculation, or when you refuse to, here are a bunch of things you please should not tell me:

f. “There just isn’t any data!” Do read that excellent thread from Robert Wiblin. Similar points hold for “you just can’t calculate this.” A decision to stick with the status quo represents an implicit, non-transparent calculation of sorts, whether you admit it or not.

g. “This would risk public confidence in the vaccine process.” Question-begging, but even if true tell us how many expected lives you are sacrificing to satisfy that end of maintaining public confidence. This same point applies to many other rejoinders. It is fine to cite additional moral values, but then tell us the trade-offs with respect to lives. Note that egalitarianism also favors First Doses First.

h. “We shouldn’t be arguing about this, we should be getting more vaccines out the door!” Yes we should be getting more vaccines out the door, but the more we succeed at that, as likely we will, the more important this dosing issue will become. Please do not try to distract our attention, this one would fail in an undergraduate class in Philosophical Logic.

i. Other fallacies, including “the insiders at the FDA don’t feel comfortable about this.” Maybe so, but then it ought to be easy enough to sketch for us in numerical terms why their reasons are good ones.

j. All other fallacies and moral failings. The most evasive of those might be: “This is all the more reason why we need to protect everyone now.” Well, yes, but still show your work and base your calculations on the level of protection you can plausibly expect, not on the level of protection you are wishing for.

At the risk of venturing into psychoanalysis, it is hard for me to avoid the feeling that a lot of public health experts are very risk-averse and they are used to hiding behind RCT results to minimize the chance of blame. They fear committing sins of commission more than committing sins of omission because of their training, they are fairly conformist, they are used to holding entrenched positions of authority, and subconsciously they identify their status and protected positions with good public health outcomes (a correlation usually but not always true), and so they have self-deceived into pursuing their status and security rather than the actual outcomes. Doing a back of the envelope calculation to support their recommendation against First Doses First would expose that cognitive dissonance and thus it is an uncomfortable activity they shy away from. Instead, they prefer to dip their toes into the water by citing “a single argument” and running away from a full comparison.

It is downright bizarre to me — and yes scandalous — that a significant percentage of public health experts are not working day and night to produce and circulate such numerical expected value estimates, no matter which side of the debate they may be on.

How many times have I read Twitter threads where public health experts, at around tweet #11, make the cliched call for transparency in decision-making? If you wish to argue against First Doses First, now it is time to actually provide such transparency. Show your work people, we will gladly listen and change our minds if your arguments are good ones.

Does Britain Have High or Low State Capacity?

Tim Harford writing at the FT covers the question “Is it even possible to prepare for a pandemic?” drawing on my paper with Tucker Omberg.

[I]n an unsettling study published late last year, the economists Robert Tucker Omberg and Alex Tabarrok took a more sophisticated look at this question and found that “almost no form of pandemic preparedness helped to ameliorate or shorten the pandemic”. This was true whether one looked at indicators of medical preparedness, or softer cultural factors such as levels of individualism or trust. Some countries responded much more effectively than others, of course — but there was no foretelling which ones would rise to the challenge by looking at indicators published in 2019. One response to this counter-intuitive finding is that the GHS Index doesn’t do a good job of measuring preparedness. Yet it seemed plausible at the time and it still looks reasonable now.

…perhaps we need to take the Omberg/Tabarrok study seriously: maybe conventional preparations really won’t help much. What follows? One conclusion is that we should prepare, but in a different way….Preparing a nimble system of testing and of compensating self-isolating people would not have figured in many 2019 pandemic plans. It will now. Another form of preparation which might yet pay off is sewage monitoring, which can cost-effectively spot the resurgence of old pathogens and the appearance of new ones, and may give enough warning to stop some future pandemics before they start. And, says Tabarrok, “Vaccines, vaccines, vaccines”. The faster our systems for making, testing and producing vaccines, the better our chances; all these things can be prepared.

One thing that did seem to matter, as Tim notes, was state capacity. In other words, it’s not so much being prepared as being prepared to act. And here I have a mild disagreement with Tim. He writes:

In an ill-prepared world, the UK is often thought to have been more ill-prepared than most, perhaps because of the strains caused by austerity and the distractions of the Brexit process.

My view is that the UK got three very important things right. The UK was the first stringent authority to approve a COVID vaccine. The UK switched to first doses first and the UK produced and ran the most important therapeutics trial, the Recovery trial. Each of these decisions and programs saved the lives of tens of thousands of Britons. The Recovery trial may have saved millions of lives worldwide.

I don’t claim that Britain did everything right, or that they did all that they could have done, but these three decisions were important, bold and correct. The coexistence of both high and low state capacity within the same nation can be surprising. The United States, for example, achieved an impressive feat with Operation Warp Speed, yet simultaneously, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) flailed and failed. Likewise, India maintains a commendable space program and an efficient electoral system, even while struggling with tasks that seem comparatively simpler, like issuing driver’s licenses.

Instead of painting countries with a broad brush of ‘high’ or ‘low’ state capacity, we should recognize multi-dimensionality and divergence. How do political will, resources, institutional robustness, culture, and history explain capacity divergence? If we understood the reasons for capacity divergence we might be able to improve state capacity more generally. Or we might better be able to assign tasks to state or market with perhaps very different assignments depending on the country.

Who was really for “focused protection of the vulnerable”?

Yes I do mean during the Covid-19 epidemic. As a follow-up post to Alex’s, and his follow-up, here are some of the effective measures in protecting the vulnerable, or they would have been more effective, had we done them better:

1. Vaccines, including speedy approval of same.

2. Prepping hospitals in January, once it became clear we should be doing so. That also would have limited lockdowns! And yet we did basically nothing.

3. Speeding up and improving the research process for anti-Covid remedies and protections.

4. First Doses First, when that policy was appropriate, among other policy ideas (NYT).

5. Effective and rapid testing equipment, readily available on the market.

If you were out promoting those ideas, you were acting in favor of protecting the vulnerable. If you were not out promoting those ideas, but instead talked about “protecting the vulnerable” in a highly abstract manner, you were not doing much to protect the vulnerable.

And here are three actions that endangered the vulnerable rather than protecting them:

5. Publishing papers suggesting a very, very low Covid-19 mortality rate, and then sticking with those results in media appearances after said results appeared extremely unlikely to be true.

6. Maintaining vague (or in some cases not so vague) affiliations with anti-vax groups.

7. Not having thought through how “herd immunity” doctrines might be modified by ongoing mutations.

Keep all that in mind the next time you hear the phrase “protecting the vulnerable.”

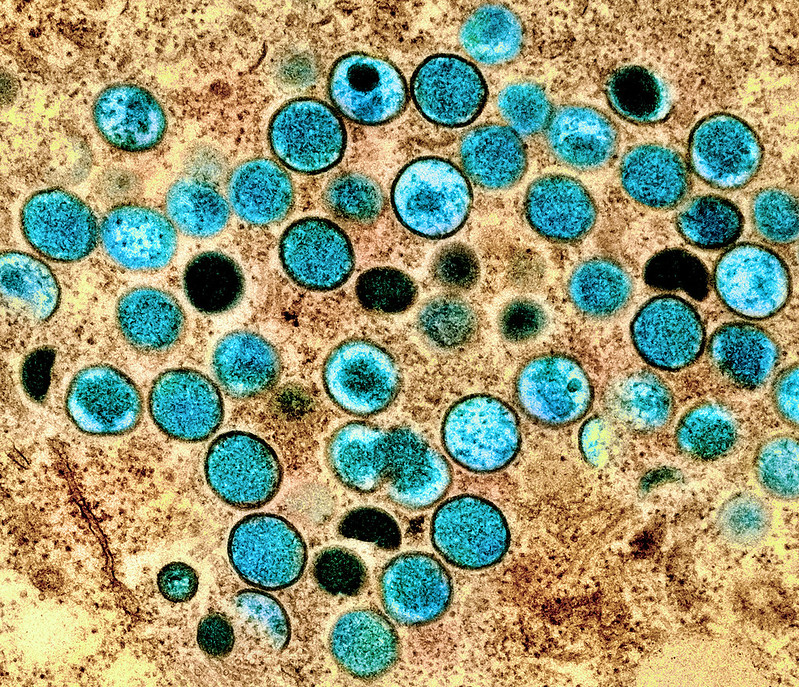

Dose Stretching for the Monkeypox Vaccine

We are making all the same errors with monkeypox policy that we made with Covid but we are correcting the errors more rapidly. (It remains to be seen whether we are correcting rapidly enough.) I’ve already mentioned the rapid movement of some organizations to first doses first for the monkeypox vaccine. Another example is dose stretching. I argued on the basis of immunological evidence that A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective Than a Full Dose of AstraZeneca and with Witold Wiecek, Michael Kremer, Chris Snyder and others wrote a paper simulating the effect of dose stretching for COVID in an SIER model. We even worked with a number of groups to accelerate clinical trials on dose stretching. Yet, the idea was slow to take off. On the other hand, the NIH has already announced a dose stretching trial for monkeypox.

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health are getting ready to explore a possible work-around. They are putting the finishing touches on the design of a clinical trial to assess two methods of stretching available doses of Jynneos, the only vaccine in the United States approved for vaccination against monkeypox.

They plan to test whether fractional dosing — using one-fifth of the regular amount of vaccine per person — would provide as much protection as the current regimen of two full doses of the vaccine given 28 days apart. They will also test whether using a single dose might be enough to protect against infection.

The first approach would allow roughly five times as many people to be vaccinated as the current licensed approach, and the latter would mean twice as many people could be vaccinated with existing vaccine supplies.

…The answers the study will generate, hopefully by late November or early December, could significantly aid efforts to bring this unprecedented monkeypox outbreak under control.

Another interesting aspect of the dose stretching protocol is that the vaccine will be applied to the skin, i.e. intradermally, which is known to often create a stronger immune response. Again, the idea isn’t new, I mentioned it in passing a couple of times on MR. But we just weren’t prepared to take these step for COVID. Nevertheless, COVID got these ideas into the public square and now that the pump has been primed we appear to be moving more rapidly on monkeypox.

Addendum: Jonathan Nankivell asked on the prediction market, Manifold Markets, ‘whether a 1/5 dose of the monkey pox vaccine would provide at least 50% the protection of the full dose?’ which is now running at a 67% chance. Well worth doing the clinical trial! Especially if we think that the supply of the vaccine will not expand soon.

Status Quo Bias

Here is the lead sentence from a CNN piece on vaccine boosters:

Even though the biopharmaceutical company Pfizer has announced that it might be time to consider giving a third dose of its coronavirus vaccine to people, many doctors and public health officials argue that it’s more beneficial to get shots into the arms of the unvaccinated right now than to boost those who are already fully vaccinated.

Delaying the 3rd dose to get out more 2nd doses is a perfectly reasonable position. What’s interesting is that today delaying the 3rd dose is conventional wisdom and yet this is exactly the same argument that I made for delaying the 2nd dose, i.e. first doses first (FDF), back in December of 2020. At that time, however, the argument was controversial. My point, isn’t that FDF has won the argument. My point is that what we are seeing, then and now, is status quo bias.

In December, status quo bias meant that people wanted to find a reason to stick with the status quo, i.e. 2 doses, and so they argued that delaying the second dose was “risky.” Today, people still want to stick with the status quo and so they argue that third doses are “risky”, i.e. delaying the third dose is now the less risky idea. The argument–it’s smart to protect more people with fewer doses–hasn’t changed but, without even realizing it, people are now making the argument that they once denied.

The logic hasn’t convinced people but previously the logic opposed the status quo and now it supports the status quo so what was once denied is now accepted. What was in December the riskier choice now becomes the safer choice. With motivated reasoning, when the motivation changes so does the reasoning.

Hat tip: Iamamish

Addendum: People will respond in the comments, but actually the situations are different. Indeed, things are different and the situation has changed. But that’s not the only or even the primary driver. If we had started with a 3-dose regimen, delaying the third dose would have seemed just as “risky” as delaying the second dose in a 2-dose regimen.

Addendum 2: The WHO today called for a moratorium on boosters until more countries are vaccinated.

Second Doses Are Better at 8 Weeks or Longer

In Britain people are now being warned *not* to get their second dose at 3 or 4 weeks because this offers less protection than waiting 8 weeks or longer.

Warnings over the lack of long-term protection offered by jab intervals shorter than eight weeks come as scores of under 40s continue to receive second doses early at walk-in clinics, contrary to Government guidance.

…“There is very good immunological and vaccine effectiveness evidence that the longer you leave that second dose the better for Pfizer and eight weeks seems to be a reasonable compromise.”

Professor Harnden emphasised that “you’re definitely less protected against asymptomatic disease if you have a shorter dose interval”.

I’m so old I can remember when first doses first wasn’t “following the science.”

Book Review: Andy Slavitt’s Preventable

Like Michael Lewis’s The Premonition which I reviewed earlier, Andy Slavitt’s Preventable is a story of heroes, only all the heroes are named Andy Slavitt. It begins, as all such stories do, with an urgent call from the White House…the President needs you now! When not reminding us (e.g. xv, 14, 105, 112, 133, 242, 249) of how he did “nearly the impossible” and saved Obamacare he tells us how grateful other people were for his wise counsel, e.g. “Jared Kushner’s name again flashed on my phone. I picked up, and he was polite and appreciative of my past help.” (p.113), “John Doer was right to challenge me to make my concerns known publicly. Hundreds of thousands of people were following my tweets…” (p. 55)

Slavitt deserves praise for his work during the pandemic so I shouldn’t be so churlish but Preventable is shallow and politicized and it rubbed me the wrong way. Instead of an “inside account” we get little more than a day-by-day account familiar to anyone who lived through the last year and half. Slavitt rarely departs from the standard narrative.

Trump, of course, comes in for plenty of criticism for his mishandling of the crisis. Perhaps the most telling episode was when an infected Trump demanded a publicity jaunt in a hermetically sealed car with Secret Service personnel. Trump didn’t care enough to protect those who protected him. No surprise he didn’t protect us.

The standard narrative, however, leads Slavitt to make blanket assertions—the kind that everyone of a certain type knows to be true–but in fact are false. He writes, for example:

In comparison to most of these other countries, the American public was impatient, untrusting, and unaccustomed to sacrificing individual rights for the public good. (p. 65)

Data from the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) show that the US “sacrifice” as measured by the stringency of the COVID policy response–school closures; workplace closures; restrictions on public gatherings; restrictions on internal movements; mask requirements; testing requirements and so forth–was well within the European and Canadian average.

The pandemic and the lockdowns split Americans from their friends and families. Birthdays, anniversaries, even funerals were relegated to Zoom. Jobs and businesses were lost in the millions. Children couldn’t see their friends or even play in the park. Churches and bars were shuttered. Music was silenced. Americans sacrificed plenty.

Some of Slavitt’s assertions are absurd.

The U.S. response to the pandemic differed from the response in other parts of the world largely in the degree to which the government was reluctant to interfere with our system of laissez-faire capitalism…

Laissez-faire capitalism??! Political hyperbole paired with lazy writing. It would be laughable except for the fact that such hyperbole biases our thinking. If you read Slavitt uncritically you’d assume–as Slavitt does–that when the pandemic hit, US workers were cast aside to fend for themselves. In fact, the US fiscal response to the pandemic was among the largest and most generous in the world. An unemployed minimum wage worker in the United States, for example, was paid a much larger share of their income during the pandemic than a similar worker in Canada, France, or Germany (and no, that wasn’t because the US replacement rate was low to begin with.)

This is not to deny that low-wage workers bore a larger brunt of the pandemic than high-wage workers, many of whom could work from home. Slavitt implies, however, that this was a “room-service pandemic” in which the high-wage workers demanded a reopening of the economy at the expense of low-wage workers. As far as the data indicate, however, the big divisions of opinion were political and tribal not by income per se. The Washington Post, for example, concluded:

There was no significant difference in the percentage of people who said social distancing measures were worth the cost between those who’d seen no economic impact and those who said the impacts were a major problem for their households. Both groups broadly support the measures.

Perhaps because Slavitt believes his own hyperbole about a laissez-faire economy he can’t quite bring himself to say that Operation Warp Speed, a big government program of early investment to accelerate vaccines, was a tremendous success. Instead he winds up complaining that “even with $1 billion worth of funding for research and development, Moderna ended up selling its vaccine at about twice the cost of an influenza vaccine.” (p. 190). Can you believe it? A life-saving, economy-boosting, pandemic ending, incredibly-cheap vaccine, cost twice as much as the flu vaccine! The horror.

Slavitt’s narrative lines up “scientific experts” against “deniers, fauxers, and herders” with the scientific experts united on the pro-lockdown side. Let’s consider. In Europe one country above all others followed the Slavitt ideal of an expert-led pandemic response. A country where the public health authority was free from interference from politicians. A country where the public had tremendous trust in the state. A country where the public were committed to collective solidarity and the public welfare. That country, of course, was Sweden. Yet in Sweden the highly regarded Public Health Agency, led by state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, an expert in infectious diseases who had directed Sweden’s response to the swine flu epidemic, opposed lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the general use of masks.

Moreover, the Public Health Agency of Sweden and Tegnell weren’t a bizarre anomaly, anti-lockdown was probably the dominant expert position prior to COVID. In a 2006 review of pandemic policy, for example, four highly-regarded experts argued:

It is difficult to identify circumstances in the past half-century when large-scale quarantine has been effectively used in the control of any disease. The negative consequences of large-scale quarantine are so extreme (forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.

Travel restrictions, such as closing airports and screening travelers at borders, have historically been ineffective.

….a policy calling for communitywide cancellation of public events seems inadvisable.

The authors included Thomas V. Inglesby, the Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, one of the most highly respected centers for infectious diseases in the world, and D.A. Henderson, the legendary epidemiologist widely credited with eliminating smallpox from the planet.

Tegnell argued that “if other countries were led by experts rather than politicians, more nations would have policies like Sweden’s” and he may have been right. In the United States, for example, the Great Barrington declaration, which argued for a Swedish style approach and which Slavitt denounces in lurid and slanderous terms, was written by three highly-qualified, expert epidemiologists; Martin Kulldorff from Harvard, Sunetra Gupta from Oxford and Jay Bhattacharya from Stanford. One would be hard-pressed to find a more expert group.

The point is not that we should have followed the Great Barrington experts (for what it is worth, I opposed the Great Barrington declaration). Ecclesiastes tells us:

… that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

In other words, the experts can be wrong. Indeed, the experts are often divided, so many of them must be wrong. The experts also often base their policy recommendations on factors beyond their expertise, including educational, class, and ideological biases, so the experts are to be trusted more on factual questions than on ethical answers. Nevertheless, the experts are more likely to be right than the non-experts. So how should one navigate these nuances in a democratic society? Slavitt doesn’t say.

Slavitt’s simple narrative–Trump bad, Biden good, Follow the Science, Be Kind–can’t help us as we try to improve future policy. Slavitt ignores most of the big questions. Why did the CDC fail in its primary mission? Indeed, why did the CDC often slow our response? Why did the NIH not quickly fund COVID research giving us better insight on the virus and its spread? Why were the states so moribund and listless? Why did the United States fail to adopt first doses first, even though that policy successfully saved lives by speeding up vaccinations in Great Britain and Canada?

To the extent that Slavitt does offer policy recommendations they aren’t about reforming the CDC, FDA or NIH. Instead he offers us a tired laundry list; a living wage, affordable housing, voting reform, lobbying reform, national broadband, and reduction of income inequality. Surprise! The pandemic justified everything you believed all along! But many countries with these reforms performed poorly during the pandemic and many without, such as authoritarian China, performed relatively well. All good things do not correlate.

Trump’s mishandling of the pandemic make it easy to blame him and call it a day. But the rot is deep. If we do not get to the core of our problems we will not be ready for the next emergency. If we are lucky, we might face the next emergency with better leadership but a great country does not rely on luck.

A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective Than a Full Dose of AstraZeneca

Today we are releasing a new paper on dose-stretching, co-authored by Witold Wiecek, Amrita Ahuja, Michael Kremer, Alexandre Simoes Gomes, Christopher M. Snyder, Brandon Joel Tan and myself.

The paper makes three big points. First, Khoury et al (2021) just published a paper in Nature which shows that “Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.” What that means is that there is a strong relationship between immunogenicity data that we can easily measure with a blood test and the efficacy rate that it takes hundreds of millions of dollars and many months of time to measure in a clinical trial. Thus, future vaccines may not have to go through lengthy clinical trials (which may even be made impossible as infections rates decline) but can instead rely on these correlates of immunity.

Here is where fractional dosing comes in. We supplement the key figure from Khoury et al.’s paper to show that fractional doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have neutralizing antibody levels (as measured in the early phase I and phase II trials) that look to be on par with those of many approved vaccines. Indeed, a one-half or one-quarter dose of the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine is predicted to be more effective than the standard dose of some of the other vaccines like the AstraZeneca, J&J or Sinopharm vaccines, assuming the same relationship as in Khoury et al. holds. The point is not that these other vaccines aren’t good–they are great! The point is that by using fractional dosing we could rapidly and safely expand the number of effective doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines.

Second, we embed fractional doses and other policies such as first doses first in a SIER model and we show that even if efficacy rates for fractional doses are considerably lower, dose-stretching policies are still likely to reduce infections and deaths (assuming we can expand vaccinations fast enough to take advantage of the greater supply, which is well within the vaccination frontier). For example, a half-dose strategy reduces infections and deaths under a variety of different epidemic scenarios as long as the efficacy rate is 70% or greater.

Third, we show that under plausible scenarios it is better to start vaccination with a less efficacious vaccine than to wait for a more efficacious vaccine. Thus, Great Britain and Canada’s policies of starting First Doses first with the AstraZeneca vaccine and then moving to second doses, perhaps with the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines is a good strategy.

It is possible that new variants will reduce the efficacy rate of all vaccines indeed that is almost inevitable but that doesn’t mean that fractional dosing isn’t optimal nor that we shouldn’t adopt these policies now. What it means is that we should be testing and then adapting our strategy in light of new events like a battlefield commander. We might, for example, use fractional dosing in the young or for the second shot and reserve full doses for the elderly.

One more point worth mentioning. Dose stretching policies everywhere are especially beneficial for less-developed countries, many of which are at the back of the vaccine queue. If dose-stretching cuts the time to be vaccinated in half, for example, then that may mean cutting the time to be vaccinated from two months to one month in a developed country but cutting it from two years to one year in a country that is currently at the back of the queue.

Read the whole thing.

The Becker-Friedman center also has a video discussion featuring my co-authors, Nobel prize winner Michael Kremer and the very excellent Witold Wiecek.

Two Vaccine Updates

First, in an article on new vaccine boosters in USA today there is this revealing statement:

Any revised Moderna vaccine would include a lower dose than the original, Moore said. The company went with a high dose in its initial vaccine to guarantee effectiveness, but she said the company is confident the dose can come down, reducing side effects without compromising protection.

Arrgh! Why wait for a new vaccine??? Fractional dosing now!

The same article also notes:

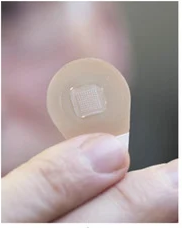

One of Moderna’s co-founders, MIT professor Robert Langer, is known for his research on microneedles, tiny Band-Aid-like patches that can deliver medications without the pain of a shot. Moderna has said nothing about delivery plans, but it’s conceivable the company might try to combine the two technologies to provide a booster that doesn’t require an injection.

The skin is highly immunologically active so you can give lower doses with a microneedle patch. The microneedles are sometimes made from sugar and don’t hurt. Microneedle delivery, however, can cause scars but I say apply the patch where the sun don’t shine and let’s go!

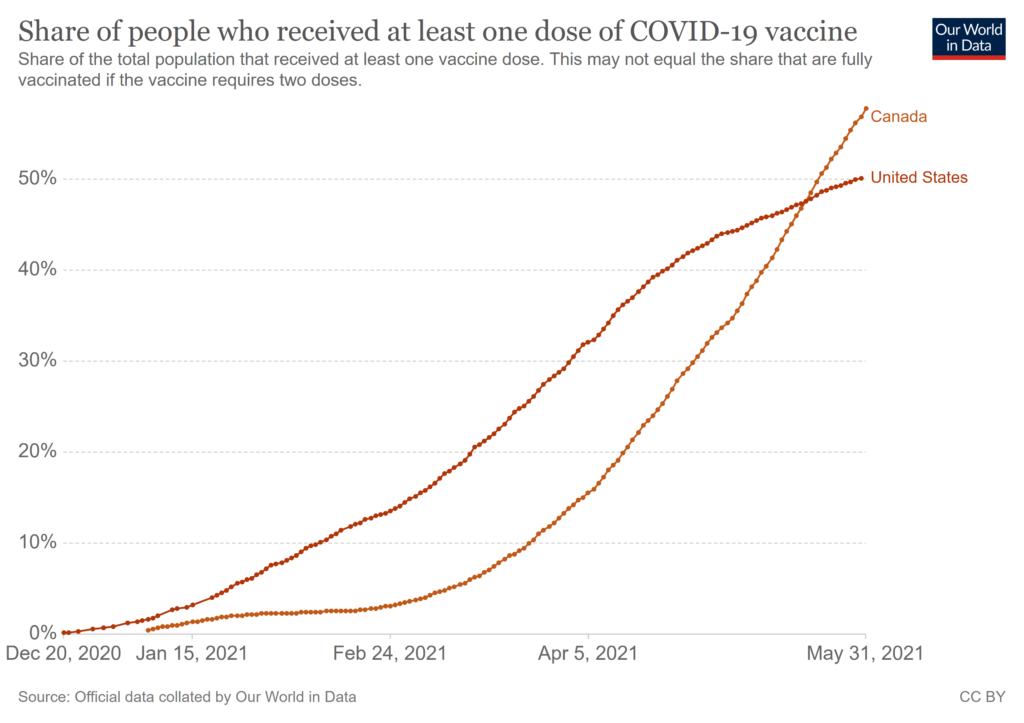

Second, Canada’s NACI has now endorsed mix and match for the AZ and Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. First Doses First has put Canada in very good shape (now ahead of the US in percent of the population with at least one dose) and this was always part of the FDF plan–delay second doses to get out more first doses and then, when supplies increase, give second doses, possibly with a better vaccine.

India Delays the 2nd Dose; Delaying 2nd Dose Improves Immune Response; Fractional Dosing

India has delayed the second dose to 12-16 weeks.

In other news, delaying the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine appears to improves the immune response (as was also found for the AstraZeneca vaccine). The latter is a news report based on a press release so some caution is warranted but frankly this was always the Bayesian bet since most vaccines have a longer time between doses as that helps the immune system. As Tyler and myself both argued, the short gap between the first and second dose was chosen to speed up the clinical trials not to maximize immunity. That was the right decision in the emergency but it was never the case that following the clinical trial regimen was “going by the science” no matter what Fauci said.

Many lives have been lost by not going to first doses first earlier, both here and in India.

Every country should move to a regimen in which the second dose comes at 12-16 weeks, even the United States, as this may improve the immune response and help other countries get a little bit ahead in their vaccine drives.

May I now also beat the drum some more on fractional dosing? Many people (not everyone) report that the second mRNA dose packs a wallop. I suspect that a half dose at 12-16 weeks would be plenty and that would free up significant capacity to vaccinate more people with first doses. We could also run some trials on half-doses for the young as a way to balance dosing and risk. Again this will matter for the rest of the world more than the United States but stretching doses in the United States will help the rest of the world and the arguments against stretching doses are now much diminished.

Atul Gawande and Zeke Emanuel Now Support Delaying the Second Dose

Many people are coming around to First Doses First, i.e delaying the second dose to ~12 weeks. Atul Gawande, for example, tweeted:

As cases and hospitalizations rise again, we can’t count on behavior alone reversing this course. Therefore, it’s time for the Biden admin to delay 2nd vax doses to 12 weeks. Getting as many people as possible a vax dose is now urgent.

Now urgent??? Yes, I am a little frustrated because the trajectory on the new variants was very clear. On January 1, for example, I wrote about The New Strain and the Need for Speed (riffing off an excellent piece by Zeynep Tufekci). Still, very happy to have Gawande’s voice added to the cause. Also joining Gawande are the power trio of Govind Persad, William F. Parker and Ezekiel J. Emanuel who in an important op-ed write:

If we temporarily delay second doses …that is our best hope of quelling the fourth wave ignited by the B.1.1.7 variant. Because we did not start this strategy earlier, it is probably too late for Michigan, New York, New Jersey and the other Northeastern states. But it might be just in time for the South and California — the next places the more infectious strain will go if historical patterns repeat.

…Drug manufacturers selected the three- or four-week interval currently used between doses to rapidly prove efficacy in clinical trials. They did not choose such short intervals based on the optimal way of using the vaccines to quell a pandemic. While a three- or four-week follow-up is safe and effective, there is no evidence it optimizes either individual benefit or population protection.

…Some complain that postponing second doses is not “following the science.” But the scientific evidence goes far beyond what was shown in the original efficacy trials. Data from the United Kingdom, Israel and now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that first doses both prevent infection and reduce transmission. In people with prior infection, experts are beginning to recognize that a second dose could provide even less benefit. Following the science means updating policies to recognize new evidence rather than stubbornly maintaining the status quo.

Emanuel is on Biden’s COVID-19 task force so consider this op-ed running the flag up the flagpole. I predict Topol will fall next.

I would be surprised, however, if the US changes course now–too many people would then ask why didn’t we do this sooner?–but dose stretching is going to be important for the rest of the world. Why aren’t we doing more to investigate fractional dosing? Even if we went to half-doses on the second dose–the full second dose appears to be strong–that would still be a significant increase in total supply.

Addendum: I have argued for sending extra doses to Michigan and other hot spots such as NJ. Flood the zone! The Biden administration says no. Why? Production is now running well ahead of distribution as more than 50 million doses have been delivered but not administered. It would be a particularly good idea to send more single-shot J&J to reach hard to reach communities–one and done.

Power Up!

Two weeks ago I was bitten by the equivalent of a radioactive spider and now I have superpowers! Including the power of immunity and the power to fly! Awesome. As I said earlier, the SARS-COV-2 virus killed more people this year than bullets “so virus immunity is a much better superpower than bullet immunity!”

I got the J&J vaccine–one of the first in the world to do so–which seemed appropriate as I have been calling for first doses first and the J&J vaccine is single dose. I will probably supplement with Novavax at a later date when supplies are plentiful.

Addendum: Also, I can get free donuts at Krispy Kreme.

Dose Stretching Policies Probably *Reduce* Mutation Risk

One objection to dose-stretching policies, such as delaying the second dose or using half-doses, is that this might increase the risk of mutation. While possible, some immunologists and evolution experts are now arguing that dose-stretching will probably reduce mutation risk which is what Tyler and I concluded. Here’s Tyler:

One counter argument is that letting “half-vaccinated” people walk around will induce additional virus mutations. Florian Kramer raises this issue, as do a number of others.

Maybe, but again I wish to see your expected value calculations. And in doing these calculations, keep the following points in mind:

a. It is hard to find vaccines where there is a recommendation of “must give the second dose within 21 days” — are there any?

b. The 21-day (or 28-day) interval between doses was chosen to accelerate the completion of the trial, not because it has magical medical properties.

c. Way back when people were thrilled at the idea of Covid vaccines with possible 60% efficacy, few if any painted that scenario as a nightmare of mutations and otherwise giant monster swarms.

d. You get feedback along the way, including from the UK: “If it turns out that immunity wanes quickly with 1 dose, switch policies!” It is easy enough to apply serological testing to a control group to learn along the way. Yes I know this means egg on the face for public health types and the regulators.

e. Under the status quo, with basically p = 1 we have seen two mutations — the English and the South African — from currently unvaccinated populations. Those mutations are here, and they are likely to overwhelm U.S. health care systems within two months. That not only increases the need for a speedy response, it also indicates the chance of regular mutations from the currently “totally unvaccinated” population is really quite high and the results are really quite dire! If you are so worried about hypothetical mutations from the “half vaccinated” we do need a numerical, expected value calculation comparing it to something we already know has happened and may happen yet again. When doing your comparison, the hurdle you will have to clear here is very high.

(See my Washington Post piece for similar arguments and additional references.).

Now here are evolutionary theorists, immunologists and viral experts Sarah Cobey, Daniel B. Larremore, Yonatan H. Grad, and Marc Lipsitch in an excellent paper that first reviews the case for first doses first and then addresses the escape argument. They make several interrelated arguments that a one-dose strategy will reduce transmission, reduce prevalence, and reduce severity and that all of these effects reduce mutation risk.

The arguments above suggest that, thanks to at least some effect on transmission from one dose, widespread use of a single dose of mRNA vaccines will likely reduce infection prevalence…

The reduced transmission and lower prevalence have several effects that individually and together tend to reduce the probability that variants with a fitness advantage such as immune escape will arise and spread (Wen, Malani, and Cobey 2020). The first is that with fewer infected hosts, there are fewer opportunities for new mutations to arise—reducing available genetic variation on which selection can act. Although substitutions that reduce antibody binding were documented before vaccine rollout and are thus relatively common, adaptive evolution is facilitated by the appearance of mutations and other rearrangements that increase the fitness benefit of other mutations (Gong, Suchard, and Bloom 2013; N. C. Wu et al. 2013; Starr and Thornton 2016). The global population size of SARS-CoV-2 is enormous, but the space of possible mutations is larger, and lowering prevalence helps constrain this exploration. Other benefits arise when a small fraction of hosts drives most transmission and the effective reproductive number is low. Selection operates less effectively under these conditions: beneficial mutations will more often be lost by chance, and variants with beneficial mutations are less certain to rise to high frequencies in the population (Desai, Fisher, and Murray 2007; Patwa and Wahl 2008; Otto and Whitlock 1997; Desai and Fisher 2007; Kimura 1957). More research is clearly needed to understand the precise impact of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 evolution, but multiple lines of evidence suggest that vaccination strategies that reduce prevalence would reduce rather than accelerate the rate of adaptation, including antigenic evolution, and thus incidence over the long term.

In evaluating the potential impact of expanded coverage from dose sparing on the transmission of escape variants, it is necessary to compare the alternative scenario, where fewer individuals are vaccinated (but a larger proportion receive two doses) and more people recover from natural infection. Immunity developing during the course of natural infection, and the immune response that inhibits repeat infection, also impose selection pressure. Although natural infection involves immune responses to a broader set of antibody and T cell targets compared to vaccination, antibodies to the spike protein are likely a major component of protection after either kind of exposure (Addetia et al. 2020; Zost et al. 2020; Steffen et al. 2020), and genetic variants that escape polyclonal sera after natural infection have already been identified (Weisblum et al. 2020; Andreano et al. 2020). Studies comparing the effectiveness of past infection and vaccination on protection and transmission are ongoing. If protective immunity, and specifically protection against transmission, from natural infection is weaker than that from one dose of vaccination, the rate of spread of escape variants in individuals with infection-induced immunity could be higher than in those with vaccine-induced immunity. In this case, an additional advantage of increasing coverage through dose sparing might be a reduction in the selective pressure from infection-induced immunity.

…In the simplest terms, the concern that dose-sparing strategies will enhance the spread of immune escape mutants postulates that individuals with a single dose of vaccine are those with the intermediate, “just right” level of immunity, more likely to evolve escape variants than those with zero or two doses (Bieniasz 2021; Saad-Roy et al. 2021)….There is no particular reason to believe this is the case. Strong immune responses arising from past infection or vaccination will clearly inhibit viral replication, preventing infection and thus within-host adaptation…. Past work on influenza has found no evidence of selection for escape variants during infection in vaccinated hosts (Debbink et al. 2017). Instead, evidence suggests that it is immunocompromised hosts with prolonged influenza infections and high viral loads whose viral populations show high diversity and potentially adaptation (Xue et al. 2017, 2018), a phenomenon also seen with SARS-CoV-2 (Choi et al. 2020; Kemp et al. 2020; Ko et al. 2021). It seems likely, given its impact on disease, that vaccination could shorten such infections, and there is limited evidence already that vaccination reduces the amount of virus present in those who do become infected post-vaccination (Levine-Tiefenbrun et al. 2021).

I also very much agree with these more general points:

The pandemic forces difficult choices under scientific uncertainty. There is a risk that appeals to improve the scientific basis of decision-making will inadvertently equate the absence of precise information about a particular scenario with complete ignorance, and thereby dismiss decades of accumulated and relevant scientific knowledge. Concerns about vaccine-induced evolution are often associated with worry about departing from the precise dosing intervals used in clinical trials. Although other intervals were investigated in earlier immunogenicity studies, for mRNA vaccines, these intervals were partly chosen for speed and have not been completely optimized. They are not the only information on immune responses. Indeed, arguments that vaccine efficacy below 95% would be unacceptable under dose sparing of mRNA vaccines imply that campaigns with the other vaccines estimated to have a lower efficacy pose similar problems. Yet few would advocate these vaccines should be withheld in the thick of a pandemic, or roll outs slowed to increase the number of doses that can be given to a smaller group of people. We urge careful consideration of scientific evidence to minimize lives lost.

The First Dose is Good

WSJ: The Covid-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE generates robust immunity after one dose and can be stored in ordinary freezers instead of at ultracold temperatures, according to new research and data released by the companies.

The findings provide strong arguments in favor of delaying the second dose of the two-shot vaccine, as the U.K. has done . They could also have substantial implications on vaccine policy and distribution around the world, simplifying the logistics of distributing the vaccine.

A single shot of the vaccine is 85% effective in preventing symptomatic disease 15 to 28 days after being administered, according to a peer-reviewed study conducted by the Israeli government-owned Sheba Medical Center and published in the Lancet medical journal. Pfizer and BioNTech recommend that a second dose is administered 21 days after the first.

The finding is a vindication of the approach taken by the U.K. government to delay a second dose by up to 12 weeks so it could use limited supplies to deliver a single dose to more people, and could encourage others to follow suit. Almost one-third of the U.K.’s adult population has now received at least one vaccine shot. Other authorities in parts of Canada and Europe have prioritized an initial shot, hoping they will have enough doses for a booster when needed.

Preliminary data also suggest that the other widely used vaccine in the U.K. developed by AstraZeneca PLC and the University of Oxford could have a substantial effect after a first dose .

The Israeli findings came from the first real-world data about the effect of the vaccine gathered outside of clinical trials in one of the leading nations in immunization against the coronavirus. Israel has given the first shot to 4.2 million people—more than two-thirds of eligible citizens over 16 years old—and a second shot to 2.8 million, according to its health ministry. The country has around 9.3 million citizens.

…”This groundbreaking research supports the British government’s decision to begin inoculating its citizens with a single dose of the vaccine,” said Arnon Afek, Sheba’s deputy director general.

The Israeli study is here. Data from Quebec also show that a single dose is highly effective, 80% or higher (Figure 3) in real world settings.

It’s becoming clearer that delaying the second dose is the right strategy but it was the right strategy back in December when I first started advocating for First Doses First. Waiting for more data isn’t “science,” it’s sometimes an excuse for an unscientific status-quo bias.

Approximately 16 million second doses have been administered in the US. If those doses had been first doses an additional 16 million people would have been protected from dying. Corey White estimates that every 4000 flu vaccinations saves a life which implies 4000 lives would have been saved by going to FDF. COVID, of course, is much deadlier than the flu–ten times as deadly or more going by national death figures (so including transmission and case fatality rate)– so 40,000 deaths is back of the envelope. Let’s do some more back-of-the-envelope calculations. Since Dec. 14, there have been approximately 10 million confirmed cases in the United States and 200,000 deaths. There are 200 million adults in the US so 1/1000 adults has died from COVID, just since Dec. 14. If we use 1/1000 as the risks of a random adult dying from COVID, then an additional 16 million vaccinations would have saved 16,000 lives. But that too is likely to be an underestimate since the people being vaccinated are not a random sample of adults but rather adults with a much higher risk of dying from COVID. Two to four times that number would not be unreasonable so an additional 16 million vaccinations might have avoided 32,000-64,000 deaths. Moreover, an additional 16 million first doses would have reduced transmission. None of these calculations is very good but they give a ballpark.

It is excellent news that the vaccine is stable for some time using ordinary refrigeration. Scott Duke Kominers and I argue that there is lot of unused vaccination capacity at the pharmacies and reducing the cold storage requirement will help to bring that unused capacity online. The announcement is also important for a less well understood reason. If Pfizer is only now learning that ultra-cold storage isn’t necessary then we should be looking much more closely at fractional dosing.

When I said that we should delay the second dose, people would respond with “but the companies say 21 days and 28 days! Listen to the science!”. That’s not scientific thinking but magical thinking. Listening to the science was understanding that the clinical trial regimen was designed at speed with the sole purpose of getting the vaccines approved. The clinical trial was not designed to discover the optimal regimen for public health. Don’t get me wrong. Pfizer and Moderna did the right thing! But it was wrong to think that the public health authorities could simply rely on “the science” as if it were written on stone. Even cold-storage wasn’t written on stone! Now that the public health authorities know that the clinical trial regimen isn’t written in stone they should be more willing to consider policies such as delaying the second dose and fractional dosing.

We are nearing the end in the US but delaying the second dose and other dose-stretching policies are going to be important in other countries.

The Big Push: A Plan to Accelerate V-Day

In the Washington Post I have an extensive piece on accelerating progress to V-day, Vaccine or Victory day, the day everyone who wants a vaccine has gotten one. I cover themes that will be familiar to MR readers, including First Doses First, Fractional Dosing, Approving More Vaccines and DePrioritization to Expand Delivery. I won’t belabor these points here but the piece is useful at collecting all the arguments in one place and there are lots of authoritative links.

One point I do want to make is that all the pieces of the “Tabarrok plan,” if you will, fit together. Namely, use First Doses First to make a big push to get as many people vaccinated with first doses as possible in the next 90 days. Approve more vaccines including Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca and others and make them available to anyone, anywhere–that is possible because these vaccines don’t require significant cold storage, J&J is a single shot and AZ is better with a second shot at 12 weeks or later all of which eases distribution.

…some people argue that adding a third (or fourth) vaccine might not help because of persistent delivery logjams at the state and local levels. But we know there is unused distributional capacity, even for the supply we do have. The United States is currently administering about 1.5 million coronavirus vaccine shots per day. While that sounds like a lot, for comparison consider that in September — during the pandemic, when social distancing measures were in full effect — we vaccinated for the seasonal flu in some weeks at the rate of 3 million people a day.

There are two main reasons the rollout has been so slow. First, the Moderna and especially the Pfizer vaccines require ultracold storage. (The Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca doses can be stored at ordinary refrigerator temperatures.) Second, we have tried to prioritize vaccinations using a confusing mishmash of age, health conditions and essential-worker status that differs by state and sometimes even by county. “Confirming such criteria is complicated at best, and it’s probably not even feasible to try under conditions of duress,” as Baylor’s Hotez puts it.

Arguments continue about prioritization lists, and the idea of tossing them entirely would cause a political fight. But there is a compromise at hand: Quickly approve the Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca vaccines and make them — and only them — available to anyone, anywhere. Keeping things simple is a sure way to increase total vaccinations. With no cold-storage requirement, the new vaccines could be administered by any of the 300,000 pharmacists and more than 1 million physicians in the United States authorized to deliver vaccines, most of whom are not now giving Pfizer or Moderna shots.