Results for “Piketty” 176 found

Peter Lindert on Piketty

He has an NBER review essay on the book. Here is one bit:

Piketty’s “r > g” device, for all its amazing rhetorical power, does not take us very far. Our task of explaining and predicting inequality movements is not made any easier by the requirement that we must first predict both a “rate of return” and the growth rate of the economy. The formula r – g takes us no further than we were transported fifty years ago by the concept of total factor productivity as a “source” of growth. It will be another “measure of our ignorance.”

Here is more:

Oddly, however, for the twentieth century trends that he and his collaborators have documented so well, the relevance of the wealth/income and capital/income ratios for the income distribution is less compelling. Across countries, the levels and movements of this ratio do not correlate well with those in income inequality. Over time, there is more correlation, within Britain, or France, or Germany, or the United States. Yet, as we shall see later, the same overall movements will show up when we look at the inequality movements in incomes that have little to do with wealth, such as wage rates or in middle/lower income ratios.

The essay is interesting throughout and you will see at the end that Lindert is no friend of inequality and no enemy of highly progressive taxation. By the way, here is a Lindert essay on three centuries of inequality in Britain and America (pdf). Here is Lindert, with Williamson, on whether globalization makes the world more unequal. He knows this area very well.

More Matt Rognlie on Piketty — the most important point

Matt has what is probably the single best, focused technical critique of Piketty. Here are his concluding remarks:

Compared to the grand scope of Piketty (2014), the objective of this note has been quite narrow: to systematically explore the relevant evidence on diminishing returns to capital. Technical and uninspiring as this question may be, it is an essential step in knowing whether the prediction of rising capital income and inequality through accumulation—a prediction that gives Capital in the Twenty-First Century its title—will really come to pass. And given the evidence here that Piketty (2014) understates the role of diminishing returns, some skepticism is certainly in order.

But rejection of this specific mechanism does not constitute rejection of all Piketty (2014)’s themes. Inequality of labor income, for instance, is a very different issue—one that remains valid and important. Capital itself remains an important topic of study. Among large developed economies, the remarkably consistent trend toward rising capital values and income is undeniable. As Sections 3.3 and 3.4 establish, this trend is a story of rising capital prices and the ever greater cost of housing—not the secular accumulation emphasized in Capital — but it has distributional consequences all the same. Policymakers would do well to keep this in mind.

The full piece is here (pdf), excellent and on target throughout.

To be perfectly frank on this one, Matt here is completely correct and Piketty has not produced any effective response to this point, either within the book or without. The internal response “I still think we need to worry about inequality therefore I side with Piketty” simply represents a misunderstanding of Matt’s argument. Piketty’s mechanism of accumulation, as laid out in his book, is simply the wrong mechanism for understanding growing inequality, both theoretically and empirically. And it is a shame that the Giles critique from the FT has attracted so much attention because it has distracted everyone from the more serious problems with the argument of the book.

Piketty v. Solow

Krusell and Smith lay out the Solow and Piketty growth models very nicely but perhaps not in a way that is immediately transparent if you are not already familiar with growth models. Thus, in this note I want to lay out the differences using the Super Simple Solow model that Tyler and I developed in our textbook. The Super Simple Solow model has no labor growth and no technological growth. Investment, I, is equal to a constant fraction of output, Y, written I=sY.

Capital depreciates–machines break, tools rust, roads develop potholes. We write D(epreciation)=dK where d is the rate of depreciation and K is the capital stock.

Now the model is very simple. If I>D then capital accumulates and the economy grows. If I<D then the economy shrinks. Steady state is when I=D, i.e. when we are investing just enough each period to repair and maintain the existing capital stock.

Steady state is thus when sY=dK so we can solve for the steady state ratio of capital to output as K/Y=s/d. I told you it was simple.

Now let’s go to Piketty’s model which defines output and savings in a non-standard way (net of depreciation) but when written in the standard way Piketty’s saving assumption is that I=dK + s(Y-dK). What this means is that people look around and they see a bunch of potholes and before consuming or doing anything else they fill the potholes, that’s dK. (If you have driven around the United States recently you may already be questioning Piketty’s assumption.) After the potholes have been filled people save in addition a constant proportion of the remaining output, s(Y-dk), where s is now the Piketty savings rate.

Steady state is found exactly as before, when I=D, i.e. dK+s(Y-dK)=dK or sY=sdK which gives us the steady level of capital to output of K/Y=s/(s d).

Now we have two similar looking expressions for K/Y, namely s/d for Solow and s/(s d) for Piketty. We can’t yet test which is correct because nothing requires that the two savings rates be the same. To get further suppose that we now allow Y to grow at rate g holding K constant, that is over time because of better technology we get more Y per unit of K. Since Y will be larger the intuition is that the equilibrium K/Y ratio will be lower, holding all else the same. And indeed when you run through the math (hand waving here) you get expressions for the Solow and Piketty K/Y ratios of s/(g+d) and s/(g+sd) respectively, i.e. a simple addition of g to the denominator in both cases (again bear in mind that the two s’s are different.)

We can now see what the models predict when g changes–this is a key question because Piketty argues that a fall in g (which he predicts) will greatly increase K/Y. Here is a table showing how K/Y changes with g in the two models. I assume for both models that d=.05, for Solow I have assumed s=.3 and for Piketty I have calibrated so that the two models produce the same K/Y ratio of 3.75 when g=.03 this gives us a Piketty s=.138.

As g falls Piketty predicts a much bigger increase in the K/Y ratio than does Solow. In Piketty’s model as g falls from .03 to .01 the capital to output ratio more than doubles! In the Solow model, in contrast, the capital to output ratio increases by only a third. Remember that in Piketty it’s the higher capital stock plus a more or less constant r that generates the massive increase in income inequality from capital that he is predicting. Thus, the savings assumption is critical.

I’ve already suggested one reason why Piketty’s saving assumption seems too strong–Piketty’s assumption amounts to a very strong belief that we will always replace depreciating capital first. Another way to see this is to ask where does the extra capital come from in the Piketty model compared to Solow? Well the flip side is that Solow predicts more consumption than Piketty does. In fact, as g falls in the Piketty model so does the consumption to output ratio. In short, to get Piketty’s behavior in the Solow model we would need the Solow savings rate to increase as growth falls.

Krusell and Smith take this analysis a few steps further by showing that Piketty’s assumptions about s are not consistent with standard maximizing behavior (i.e. in a model in which s is allowed to vary to maximize utility) nor do they appear consistent with US data over the last 50 years. Neither test is definitive but both indicate that to accept the Piketty model you have to abandon Solow and place some pretty big bets on a non-standard assumption about savings behavior.

Piketty responds to critics

Is Piketty’s “Second Law of Capitalism” fundamental?

Per Krusell and Tony Smith have a new paper on Piketty (pdf), which I take to be reflecting a crystallization of opinion on the theory side. Here is one excerpt:

There are no errors in the formula Piketty uses, and it is actually consistent with the very earliest formulations of the neoclassical growth model, but it is not consistent with the textbook model as it is generally understood by macroeconomists. An important purpose of this note is precisely to relate Piketty’s theory to the textbook theory. Those of you with standard modern training have probably already noticed the difference between Piketty’s equation and the textbook version that we are used to. In the textbook model, the capital-to-income ratio is not s=g but rather s/(g+ δ), where δ is the rate at which capital depreciates. With the textbook formula, growth approaching zero would increase the capital-output ratio but only very marginally; when growth falls all the way to zero, the denominator would not go to zero but instead would go from, say 0.12—with g around 0.02 and δ = 0.1 as reasonable estimates—to 0.1. As it turns out, however, the two formulas are not inconsistent because Piketty defines his variables, such as income, y, not as the gross income (i.e., GDP) that appears in the textbook model but rather as income, i.e., income net of depreciation. Similarly, the saving rate that appears in the second law is not the gross saving rate as in the textbook model but instead what Piketty calls the “net saving rate”, i.e., the ratio of net saving to net income.

Contrary to what Piketty suggests in his book and papers, this distinction between net and gross variables is quite crucial for his interpretation of the second law when the growth rate falls towards zero. This turns out to be a subtle point, because on an economy’s balanced growth path, for any positive growth rate g, one can map any net saving rate into a gross saving rate, and vice versa, without changing the behavior of capital accumulation. The range of net saving rates constructed from gross saving rates, however, shrinks to zero as g goes to zero: at g = 0, the net saving rate has to be zero no matter what the gross rate is, as long as it is less than 100%. Conversely, if a positive net saving rate is maintained as g goes to zero, the gross rate has to be 100%. Thus, at g = 0, either the net rate is 0 or the gross rate is 100%. As a theory of saving, we maintain that the former is fully plausible whereas the latter is all but plausible.

With the upshot coming just a wee bit later:

…Moreover, whether one uses the textbook assumption of a historically plausible 30% saving rate or an optimizing rate, when growth falls drastically—say, from 2% to 1% or even all the way to zero—then the capital-to-income ratio, the centerpiece of Piketty’s analysis of capitalism, does not explode but rather increases only modestly. In conclusion, at least from the perspective of the theory that we are more used to and find more a priori plausible, the second law of capitalism turns out to be neither alarming nor worrisome, and Piketty’s argument that the capital-to-income ratio is poised to skyrocket does not seem well-founded. [emphasis added by TC]

Krusell and Smith really know their stuff on this topic and their arguments to me seem completely correct.

By the way, here is a Chris Giles follow-up post from The FT, very useful.

What do the Piketty data problems really mean?

In some ways the new FT criticisms may not matter much, although I think not in a way which is reassuring for Piketty. There were already several major problems with Piketty’s analysis and also empirics, including what Alex has called the asset price problem. He wrote:

According to four French economists, Piketty’s measure of the capital stock is greatly influenced by the Europe-US housing bubble that preceded the financial crisis.

Adjusting for that factor seems to make the main results go away, and that is a purely empirical problem which has not been answered, at least not yet.

Another pre-existing empirical problem is that 19th century data seem to indicate that a “Piketty world,” even if we take it on its own terms, far from being a disaster, would likely be accompanied by rising real wages and declining consumption inequality, albeit rising wealth inequality.

That hasn’t been answered either, although a few people have suggested (without serious back-up) that if wealth inequality is going up that has to lead to political problems, or problems of some kind or another, and thus it can’t be something we can approve of or accept with equanimity, because inequality is really really bad, and therefore Piketty is somehow right anyway. That’s a weak response to begin with and furthermore it doesn’t fit the available data.

Empirically, inheritances aren’t nearly as important as Piketty seems to suggest.

On Twitter Clive Crook wrote of the:

…distance between treacherous data and super-bold conclusions an issue at the outset. This underlines the point.

Now, when you cut through the small stuff, the new empirical problem seems to be that UK revisions, combined with a population-weighted series for Europe, contradicts Piketty’s claim of rising wealth inequality for Europe. I would call that a serious problem. I am not impressed by the “downplaying” responses which focus on coding errors, Swedish data points, and the other small stuff. Let’s face up to the real (new) problem, namely that robustness suddenly seems much weaker. You can’t argue that population-weighting is “the right way to do it,” but it is an entirely plausible way to estimate the wealth inequality trend. If Piketty’s results don’t survive population weighting (and what are apparently the superior UK numbers), that suggests the overall rise in European wealth inequality is not very robust to how the pie is carved up and also that it is not backed by dominant, “rule the roost” sorts of forces.

It should be noted that Piketty’s response to the new criticisms was quite weak. Maybe he’s not to be blamed for what was surely a rapid and caught-off-guard response, and perhaps there is more to come, but it doesn’t reassure me either. He also should have run it by a PR person first (for instance, don’t start your response with a sentence ending in an exclamation point.)

That said, don’t focus on Piketty. When evaluating debates of this kind, never ever confuse a) is he right? with b) “how much should we raise/lower the relative status of the author as a result of the new exchange”? So responses like “he made all his data freely available,” or “he admits all along how complicated this all is,” address b) but not the more important a). And if you are seeing people focus on b) rather than a), they have a problem themselves. On empirical grounds it does seem we have another reason for thinking Piketty’s central claim isn’t quite right, at least not for the reasons he sets out, and perhaps not quite right altogether.

Addendum: Ryan Avent has a good survey of some key issues and responses.

Piketty update

…according to a Financial Times investigation, the rock-star French economist appears to have got his sums wrong.

The data underpinning Professor Piketty’s 577-page tome, which has dominated best-seller lists in recent weeks, contain a series of errors that skew his findings. The FT found mistakes and unexplained entries in his spreadsheets, similar to those which last year undermined the work on public debt and growth of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff.

The central theme of Prof Piketty’s work is that wealth inequalities are heading back up to levels last seen before the first world war. The investigation undercuts this claim, indicating there is little evidence in Prof Piketty’s original sources to bear out the thesis that an increasing share of total wealth is held by the richest few.

Prof Piketty, 43, provides detailed sourcing for his estimates of wealth inequality in Europe and the US over the past 200 years. In his spreadsheets, however, there are transcription errors from the original sources and incorrect formulas. It also appears that some of the data are cherry-picked or constructed without an original source.

For example, once the FT cleaned up and simplified the data, the European numbers do not show any tendency towards rising wealth inequality after 1970. An independent specialist in measuring inequality shared the FT’s concerns.

The full FT story is here.

Addendum: Here is the in-depth discussion. Here is Piketty’s response.

The Piketty Bubble?

Piketty’s Capital is not very clear on how to distinguish greater physical capital from higher asset prices. For the most part, Piketty discusses capital as something that builds up over time through savings. The increase in physical capital then generates large returns to rentiers and those returns increases the capital share of income. When it comes to measuring capital, however, this has to be done in money terms which means that we need the price of capital. But the price of capital can vary significantly; as a result, Piketty’s capital stock can vary significantly even without changes in physical capital or savings. When capital increases because of changes in its price, however, the implications are quite different from a physical increase in capital.

Consider an asset that pays a dividend D forever; at interest rate r the asset is worth P=D/r. As r falls, the price of the asset rises. An asset that pays $100 forever is worth $1000 at an interest rate of 10% (.1) but $2000 at an interest rate of 5%. Piketty measures a higher P as more capital but notice that P is high only because r is low. You can’t, therefore, multiply P by some fixed r and conclude that rents have increased. Indeed, in this case rents, the dividend, haven’t increased at all. For the most part, Piketty simply ignores this issue (at least in the book) by arguing that changes in the price of capital wash out over long time periods but that does not appear to be the case in his data.

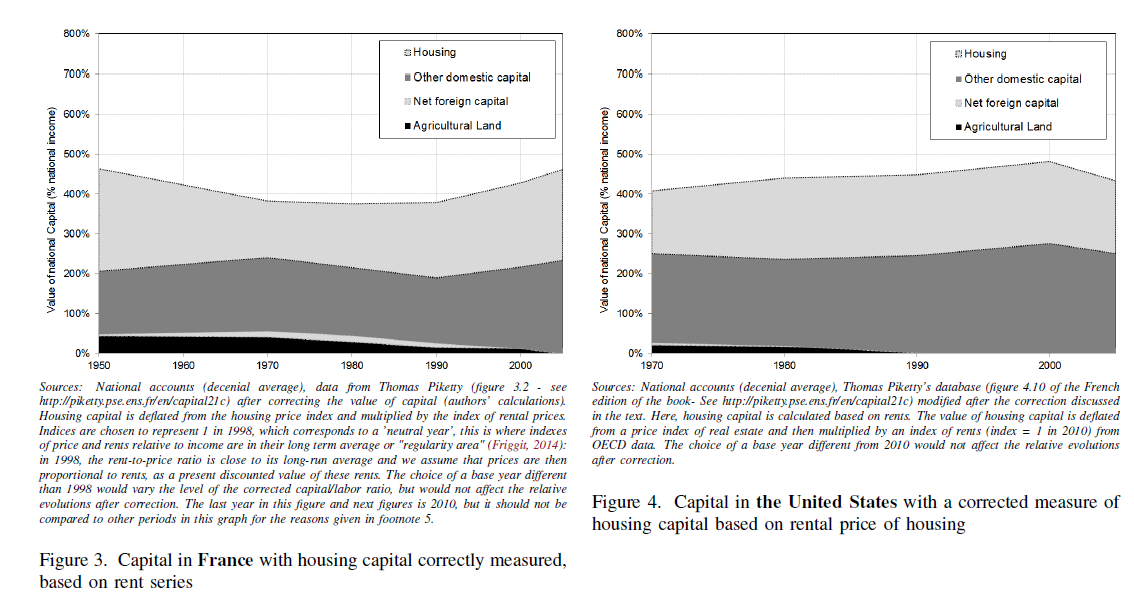

According to four French economists, Piketty’s measure of the capital stock is greatly influenced by the Europe-US housing bubble that preceded the financial crisis (Tyler earlier pointed to the French version of this paper, this is the English version). Since Piketty’s theory is based on rents from physical capital, the authors suggest that measures of housing capital based on prices should be corrected using the rent to price ratio. In other words, if the rentiers aren’t getting more rents then their capital hasn’t really increased. When measured in this way, the authors find little to no increase in the capital stock in either France or the United States.

Addendum: Do note that the debate here is not about income inequality but rather the source of income inequality and the implications for the future that Piketty draws from a (possibly not) rising capital stock.

Stefan Homburg on Piketty

It is a useful overview (pdf, but better link here) of some of the major problems in the argument, here is one key passage:

Piketty’s erroneous claim is due to the implicit assumption that savings are never consumed, nor spent on charitable purposes or used to exert power over others. It is only under this outlandish premise that wealth grows at the rate r. If people use their savings later on, as they do in the Diamond model as well as in reality, the growth of wealth is independent of the return on capital. This holds all the more in the presence of taxes.

Piketty’s allegation that the relationship r>g implies a rising wealth-income ratio is not only logically flawed, however, but also rebutted by his own data: On p. 354, the author reports that the return on capital has consistently exceeded the world growth rate over the last 2,000 years. According to his “central contradiction of capitalism”, this would have implied steadily increasing wealth-income ratios. Yet, over the last two centuries or so, the period for which data are available, wealth-income ratios have remained relatively stable in countries like the United States or Canada. In countries such as Britain, France, or Germany, which were heavily affected by the wars, wealth-income ratios declined at the start of World War I and recovered after the end of World War II. The book’s references to these wars and the implied destruction of capital abound. They are intended to rescue the claim that r>g implies an ever rising wealth-income ratio. The United States and Canada as obvious counter-examples remain unmentioned in this context.

For the pointer I thank David Levey.

Aaron Hedlund on Piketty

He writes me in an email:

I feel comfortable saying that his extensive documentation of inequality– it’s trends, composition, etc.– is a big contribution that should drive future research.

…the thesis that r > g is the explanation for inequality or an ominous predictor of future inequality is, to be blunt, ridiculous.

1) Consider the most basic economic growth model: the Solow model where households arbitrarily follow a constant savings rate rule. In that model, the long-run growth rate equals the rate of technological progress, and the rate of return to capital is constant and completely independent of that growth rate. Therefore, you could have r > g, r = g, or r < g, simply because there is NO relationship. In that model, the capital/output ratio is stable in the long-run, again regardless of what r is relative to g.

We could beef the model up a bit by allowing households to actively choose how much to save (rather than impose a constant savings rate rule on them). In that model, the economy will also get to a point with stable long-term growth where the growth rate is determined purely by technological progress. In that model under log utility, 1 + r = (1 + g)*(1 + rate of time preference). As long as people are at all impatient, the implication is r > g. Therefore, the economy will have r > g, stable growth, and a stable K/Y ratio.

The flaw with both of these models, of course, is that they are representative household models where there is no inequality. Therefore, we can go a step further and add uninsurable risk to the model (whether that be health risk, earnings risk, or any other important source of economic risk). In *these* models, households also engage in precautionary savings, so in equilibrium r is lower than it is in the rep agent models. In fact, the greater amount of risk, the more wealth inequality and the SMALLER the gap between r and g.

2) Another huge fallacy is to translate “r > g” as “the return to capital is greater than the rate of return to labor.” The notion “rate of return” indicates an intertemporal dimension: for example, if I invest $1, how much do I get back in return a year later? The growth rate of the economy is not the return to labor. In fact, the “return” to labor is static: I give up x units of time in exchange for y dollars.

The RELEVANT comparison would be to compare the rate of return on capital to the rate of return on investing in human capital (ie you go to college and then reap labor market rewards in the future). The rate of return on human capital is most definitely not just “g.” In fact, the college premium is at an all-time high, which suggests that the rate of return on human capital is quite high and very possibly higher than the rate of return on physical capital.

3) The r > g –> inequality thesis is also based on ignoring the fact that r and g are both determined in equilibrium. Here’s what I mean: it is bad economics to say “Look, r > g, therefore IF people behave in such and such manner, their wealth will grow at a higher rate than g indefinitely.” The reason it is bad economics is because you can’t take the “r > g” as given and THEN impose whatever behavioral assumptions you want. The fact is, people’s behavior affects r and g. In the heterogeneous models I mentioned above, r > g, inequality is STABLE, and the behavior of households is determined by their desire to maximize utility. If I were to go to the model and arbitrarily force the households to behave differently, then the equilibrium r would change.

Here is Hedlund’s home page.

Why Piketty’s book is a bigger deal in America than in France

On The Upshot I have a new piece, co-authored with Veronique de Rugy, here is an excerpt:

…the book’s timing may be behind the state of French debate. Had it been released in the halcyon days of Mr. Hollande’s 2011 presidential campaign, when many French considered soak-the-rich talk and 75 percent marginal tax rates to be practical fiscal strategies, Mr. Piketty’s book might have made a bigger splash in France. Today, with the economy still struggling, Mr. Hollande is talking about tax cuts rather tax increases. The 75 percent rate has suffered constitutional challenges, and even celebrity backlashes, such as when Gérard Depardieu pursued and received Russian citizenship to lower his tax rate. Mr. Hollande seems to be steering France away from its traditional role as a defender of high taxes and toward some structural reforms, albeit at a slow pace. During his New Year address, Hollande even turned into a rhetorical supply-sider, making the case for cutting taxes and public spending, improving competitiveness, and creating a more investor-friendly climate. In any case, the French appetite for stiff tax increases has diminished.

…Finally, some other French economists have taken the lead in challenging Mr. Piketty’s empirical claims. One recent paper by four economists at l’Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris challenges Mr. Piketty’s view that inequality has increased because the return to capital has been greater than general growth in the economy. The current shorthand is “r > g.”

The paper argues that the higher growth of capital rests entirely on returns to housing, and takes technical issues with the book’s treatment of housing, too. If Mr. Piketty’s argument depends on housing, it hardly seems to match his basic story about the ongoing ascendancy of capitalists.

There is much more at the link.

Updated Priors (Ryan Decker) reviews Piketty

Here is one good part of a consistently good and interesting review:

Most of the analysis in the book is more about accounting than economics. Piketty takes nearly everything as exogenous then divides things arithmetically. His ubiquitous r > g heuristic takes both sides of the inequality as given for almost the entire book. Lines like “the richest 10 percent appropriate three-quarters of the growth” (297) enable lazy readers to avoid thinking about what actually determines income. Language about “appropriation” suggests that we live in an endowment economy, as does the claim that post-World War I wealth inequality fell “so low that nearly half the population were able to acquire some measure of wealth” (350). Endogeneity, anyone? Taking income as exogenous leads to other large problems with inference, such as the claim that “meritocratic extremism can thus lead to a race between supermanagers and rentiers, to the detriment of those who are neither” (417). Piketty does not consider the possibility that this race results in more income than otherwise, nor does he consider the notion that an increase in the bargaining power of elite executives could actually come at the expense of capital owners rather than workers. I’m not making an argument for either here; I’m simply suggesting that Piketty’s ideological quips don’t deserve the certainty with which he delivers them. Models with endowment economies have their purposes, but a 600-page book should be able to relax such strict assumptions. His criticisms of mathematical economics (32, 574) are not surprising given that he relies so heavily on assumptions and mechanisms that would be highly vulnerable to criticism if they were forced into the transparency of a formal model.

Hat tip goes to Angus.

Garett Jones reviews Piketty

Here is one bit:

Market-oriented economies that learn to live with inequality will reap the rewards: More domestic capital for workers to use on their jobs, more foreign capital flowing in to a country perceived as a safe investment, and a political and cultural system that can spend its time on topics other than the 1 percent. Market-oriented economies that instead follow Piketty’s preferred path—taxing capital heavily, preferably through international consortiums so the taxes are harder to evade—will end up with less domestic and foreign capital, fewer lenders willing to fund new housing projects, fewer new office buildings, and a cultural system focused on who has more and who has less.

…The Boston University economist Christophe Chamley and the Stanford economist Kenneth Judd came up independently with what we might call the Chamley-Judd Redistribution Impossibility Theorem: Any tax on capital is a bad idea in the long run, and that the overwhelming effect of a capital tax is to lower wages. A capital tax is such a bad idea that even if workers and capitalists really were two entirely separate groups of people—if workers could only eat their wages and capitalists just lived off of their interest like a bunch of trust-funders—it would still be impossible to permanently tax capitalists, hand the tax revenues to workers, and make the workers better off.

And:

…One lesson of this story is that it’s good to be patient. So let’s start training ourselves and our children to delay gratification, to forego that great sound system on the new car, to eat at home a little more often.

The full review is here.

The policy proposals Thomas Piketty forgot to mention

Suresh Naidu writes:

…let me suggest that if we’re aiming for politically hopeless ideas, open migration is as least as good as the global wealth tax in the short run, and perhaps complementary.One weakness of the book is its focus on the large core economies (the data obviously is better and the wealth is obviously larger). But liberalizing immigration, while not solving the ultimate problem the book diagnoses, can go some of the way by raising growth of both income and population.

Maybe, that will likely improve welfare but in an Alvin Hansen model it can make Piketty-like phenomena (I won’t call them problems) more extreme. In any case there are more straightforward remedies. Social Security privatization is another option, if r > g is truly such a likelihood. Yet Piketty and his boosters won’t mention this. By the way, I am opposed to social security privatization — scroll down in that link — but I probably would favor it if it my views were closer to Piketty’s.

Here is a somewhat biting paragraph on Piketty and policy from my Foreign Affairs review (use “open private window” in Firefox, if need be):

Piketty also ignores other problems that would surely stem from so much wealth redistribution and political control of the economy, and the book suffers from Piketty’s disconnection from practical politics — a condition that might not hinder his standing in the left-wing intellectual circles of Paris but that seems naive when confronted with broader global economic and political realities. In perhaps the most revealing line of the book, the 42-year-old Piketty writes that since the age of 25, he has not left Paris, “except for a few brief trips.” Maybe it is that lack of exposure to conditions and politics elsewhere that allows Piketty to write the following words with a straight face: “Before we can learn to efficiently organize public financing equivalent to two-thirds to three-quarters of national income” — which would be the practical effect of his tax plan — “it would be good to improve the organization and operation of the existing public sector.” It would indeed. But Piketty makes such a massive reform project sound like a mere engineering problem, comparable to setting up a public register of vaccinated children or expanding the dog catcher’s office.

Here is another:

Worse, Piketty fails to grapple with the actual history of the kind of wealth tax he supports, a subject that has been studied in great detail by the economist Barry Eichengreen, among others. Historically, such taxes have been implemented slowly, with a high level of political opposition, and with only modestly successful results in terms of generating revenue, since potentially taxable resources are often stashed in offshore havens or disguised in shell companies and trusts. And when governments have imposed significant wealth taxes quickly — as opposed to, say, the slow evolution of local, consent-based property taxes — those policies have been accompanied by crumbling economies and political instability.

The simple fact is that large wealth taxes do not mesh well with the norms and practices required by a successful and prosperous capitalist democracy. It is hard to find well-functioning societies based on anything other than strong legal, political, and institutional respect and support for their most successful citizens. Therein lies the most fundamental problem with Piketty’s policy proposals: the best parts of his book argue that, left unchecked, capital and capitalists inevitably accrue too much power — and yet Piketty seems to believe that governments and politicians are somehow exempt from the same dynamic.

And finally the review closes with this:

A more sensible and practicable policy agenda for reducing inequality would include calls for establishing more sovereign wealth funds, which Piketty discusses but does not embrace; for limiting the tax deductions that noncharitable nonprofits can claim; for deregulating urban development and loosening zoning laws, which would encourage more housing construction and make it easier and cheaper to live in cities such as San Francisco and, yes, Paris; for offering more opportunity grants for young people; and for improving education. Creating more value in an economy would do more than wealth redistribution to combat the harmful effects of inequality.

The original pointer to the first link was from Henry Farrell. And my previous criticisms of Piketty on the analytics are here. Barry Eichengreen on wealth taxes is here.

Why I am not persuaded by Thomas Piketty’s argument

My Foreign Affairs review is here. (Open up “New private window” in Firefox, if need be.) I won’t attempt to cover all of the review, but rather will rephrase a few of my points for MR readers, in slightly different terminology:

1. If the rate of return remains higher than the growth rate of the economy, wages are likely to rise and quite a bit. You can find a wonky version of that idea here from Matt Rognlie. But it suffices to apply common sense, namely that capital accumulation bids up wages. Piketty suggests we are headed back to something resembling the 19th century. Well, that was a pretty good time for the average working person in Western Europe, especially once we get past the first part of that century, which had lots of war and a still-incomplete industrial revolution.

Since we today have had some wage stagnation, perhaps it does not feel that kind of favorable outcome is what we will get and many commentators are trading off this mood. But also realize the (risk-adjusted) return on capital hasn’t been that high lately and it has been falling for decades. This combination of variables — low returns and stagnant wages — does not refute Piketty but it doesn’t exactly fit into his mold either.

2. The crude seven-word version of Piketty’s argument is “rates of return on capital won’t diminish.” Is that really such a powerful forecast? I say over the next fifty or one hundred years we don’t have a very good sense of which factors will show diminishing returns and which will not. It is hard enough to make predictions of trend over a twenty-year time horizon. NB: At many points in the Piketty book he seeks to have it both ways: loads of caveats, but then he falls back into the basic model, and he and his defenders cite the caveats when it is convenient.

3. Piketty’s reasons why rates of return on capital won’t diminish are fairly specific and restricted to only a small share of capital. He cites advanced financial management techniques of the very wealthy and also investing abroad in emerging economies. Neither of these covers most capital, and thus capital returns as a whole may not be so robust. Nor is it obvious that either technique will prove especially successful over the next few decades or longer. Again, is there any particular reason to think either of these factors will outrace the basic logic of diminishing returns, or for that matter EMH, relative to other factor returns that is? They might, to be sure. They also might underperform. In any case this is pure speculation and Piketty’s entire argument depends upon it.

4. The actual increases in income inequality we observe are mostly about labor income, not capital income. They don’t fit easily into Piketty’s story and arguably they don’t fit into the story at all.

5. Piketty converts the entrepreneur into the rentier. To the extent capital reaps high returns, it is by assuming risk (over the broad sweep of history real rates on T-Bills are hardly impressive). Yet the concept of risk hardly plays a role in the major arguments of this book. Once you introduce risk, the long-run fate of capital returns again becomes far from certain. In fact the entire book ought to be about risk but instead we get the rentier.

Overall, the main argument is based on two (false) claims. First, that capital returns will be high and non-diminishing, relative to other factors, and sufficiently certain to support the r > g story as a dominant account of economic history looking forward. Second, that this can happen without significant increases in real wages.

Addendum: Still, it is a very important book and you should read and study it! But I’m not convinced by the main arguments, and the positive reviews I have read worsen rather than alleviate my anxieties. I’ll cover the policy and politics of this book in a separate post. Do read my review itself, which has much more than what is in this blog post.