Results for “age of em” 15633 found

On the GDP-Temperature relationship and its relevance for climate damages

I have worried about related issues for some while, and now that someone has done the hard work I find the results disturbing and possibly significant:

Econometric models of temperature impacts on GDP are increasingly used to inform global warming damage assessments. But theory does not prescribe estimable forms of this relationship. By estimating 800 plausible specifications of the temperature-GDP relationship, we demonstrate that a wide variety of models are statistically indistinguishable in their out-of-sample performance, including models that exclude any temperature effect. This full set of models, however, implies a wide range of climate change impacts by 2100, yielding considerable model uncertainty. The uncertainty is greatest for models that specify effects of temperature on GDP growth that accumulate over time; the 95% confidence interval that accounts for both sampling and model uncertainty across the best-performing models ranges from 84% GDP losses to 359% gains. Models of GDP levels effects yield a much narrower distribution of GDP impacts centered around 1–3% losses, consistent with damage functions of major integrated assessment models. Further, models that incorporate lagged temperature effects are indicative of impacts on GDP levels rather than GDP growth. We identify statistically significant marginal effects of temperature on poor country GDP and agricultural production, but not rich country GDP, non-agricultural production, or GDP growth.

That is from Richard G Newell, Brian C. Prest, and Steven E. Sexton. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Neil Tambe on Courage Studies (from my email)

Most importantly, happy holidays to you and your family. Thank you (and Alex) for another year of MR and CWT.

I wanted to suggest that you involve the theme of courage into your various projects. For the purpose of this message, my working definition of courage is the capability to do the right or needed thing, even though one knows it will be difficult.

Several recent posts in MR have a question of courage at their foundation. For example, reasonable people could agree that accelerating vaccine approvals by eliminating conventional but unnecessary bureaucracy, crossing the fault lines of polarized political issues, taking a risk to start a business, implementing provocative new ideas for democracy and liberalism, or launching a project within a corporation that improves productivity might all be “right” to do.

And yet they don’t happen. Why?

To be sure, there are many explanations. That said, I’ve spent my career operating in large organizations and I’ve come to observe a common thread – courage.

Teams and individuals often have motivation, skill, and even the power to do the “hard but important stuff” like the ones I’ve listed. But we pass. We aren’t willing to go out on a limb. We follow conventional courses of action even though they don’t live up to our ideals. If we only had the courage to act.

Again, there are many other reasons why hard stuff doesn’t get done. Courage, in my observation, is a fundamental one but not an idea that is well understood.

Much like you’ve suggested “Progress Studies” as a discipline in its own right, I’d suggest “Courage Studies” (the study of what courage is and how to cultivate it) as a relevant sub-discipline within the domain of Progress.

I’m particularly interested in this area, and doing my own writing here, so I acknowledge that this point of view is biased by my own interests. I won’t be shy about submitting my work to Emergent Ventures once a manuscript is transcribed from my handwritten notebook!

In the meantime, I’m happy to share more detailed ideas on “Courage Studies” if they’d be helpful to you or your team.

Paul McCartney as management study

I am listening to McCartney III, the new Paul album, recorded at age 78 with Paul playing all of the instruments and doing all of the production at home. There is no “Hey Jude” on here, but it is pretty good and given the broader context it is remarkable. I recently linked to an Ian Leslie post on 64 reasons why Paul is underrated, but I don’t think he comes close to the reality.

Paul has been writing songs and performing since 1956, with no real breaks. Perhaps he has written more hit songs than anyone else. He brought the innovations of Cage and Stockhausen into popular music, despite having no musical education and growing up in the Liverpool dumps. His second act, Wings, sold more records in its time than the Beatles did. On a lark he decided to learn techno/EDM and put out five perfectly credible albums in that area. He decided to learn how to compose classical music, and after some initial missteps his Ecce Cor Meum is perhaps the finest British choral work in a generation, worthy of say Britten or Nicholas Maw. And that is from a guy who can’t really read music. He has learned how to play most of the major musical instruments, typically well. He can compose and play and perform in virtually every musical genre, including heavy metal, blues, music hall, country and western, gospel, show tunes, ballads, rockers, Latin music, pastiche, psychedelia, electronic music, Devo-style robot-pop, drone, lounge, reggae, and more and more and more.

His vocal range once spanned over four octaves, he is sometimes considered the greatest bass player in the history of rock and roll, and he was the first popular musician to truly master the recording studio, again with zero initial technical or musical education of any sort.

He is perhaps the quickest learner the music world ever has seen.

He has collaborated with John Lennon, George Harrison, George Martin, Ravi Shankar, Jimmy McCullough, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Elvis Costello, Carl Perkins, Kiri Te Kanawa, David Gilmour, Kanye West, Rihanna, and numerous others. He wrote the best theme song for any James Bond movie. He was the workaholic of the Beatles. He was one of the most influential individuals worldwide, including behind the Iron Curtain, in the 1960s and sometimes beyond.

He was a very keen businessman in buying up the rights to music IP at just the right time, making him a billionaire.

He is OK enough as a painter, has been an effective propagandist for vegetarianism, active in numerous charities, and has put out two (?) children’s books, which I strongly doubt are ghostwritten. He has been very active as a father in raising five children, while touring regularly, often intensely. He had planned to be touring this summer at age 78, with a world class show spanning two and a half hours with Paul taking no break or even letting up (I saw the previous tour).

There is no backward-bending supply curve for this one.

If you are looking to study careers, Paul McCartney’s career is one of the very best and most instructive.

Micro-hemorrhages and the importance of vaccination

Neurological manifestations are a significant complication of coronavirus infection disease-19 (COVID-19). Understanding how COVID-19 contributes to neurological disease is needed for appropriate treatment of infected patients, as well as in initiating relevant follow-up care after recovery. Investigation of autopsied brain tissue has been key to advancing our understanding of the neuropathogenesis of a large number of infectious and non-infectious diseases affecting the central nervous system (CNS). Due to the highly infectious nature of the etiologic agent of COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), there is a paucity of tissues available for comprehensive investigation. Here, we show for the first time, microhemorrhages and neuropathology that is consistent with hypoxic injury in SARS-CoV-2 infected non-human primates (NHPs). Importantly, this was seen among infected animals that did not develop severe respiratory disease. This finding underscores the importance of vaccinating against SARS-CoV-2, even among populations that have a reduced risk for developing of severe disease, to prevent long-term or permanent neurological sequelae. Sparse virus was detected in brain endothelial cells but did not associate with the severity of CNS injury. We anticipate our findings will advance our current understanding of the neuropathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection and demonstrate SARS-CoV-2 infected NHPs are a highly relevant animal model for investigating COVID-19 neuropathogenesis among human subjects.

That is from new Fast Grants supported research by Tracy Fischer, et.al. And here are some related earlier results from Kabbani and Olds. Here are some more general recent results about brain damage.

How bad are these micro-hemorrhages anyway? I don’t know! You may notice I have hardly lunged at the “permanent damage” papers that have been coming out on Covid (in fact many of them already have collapsed or not replicated). But there are genuine reasons for caution, these results do not seem to be collapsing, and Covid-19 is not just a bunch of people trying to make a mountain out of a molehill. And “exposing the young” decisions should not be taken lightly either. The people who are very cautious about reopening may be too risk-averse given realistic alternatives, but they are not all just statists, Trump haters, lazy teachers’ unions, and so on. There are very genuine concerns here.

Minimum wage laws during a pandemic

From Michael Strain at Bloomberg:

In July 2019, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that a $15 minimum wage would eliminate 1.3 million jobs. The CBO also forecast that such an increase would reduce business income, raise consumer prices, and slow the economy.

The U.S. economy will be very weak throughout 2021. The nation will need more business income, not less; more jobs, not fewer; and faster, not slower, economic growth. A $15 minimum wage would move the economy in the wrong direction across all these fronts.

I fully agree, and in fact would go further. On Twitter I wrote in response to Noah:

Surely in a pandemic these businesspeople are right and the accumulated non-pandemic research literature doesn’t apply so much, right? Pretty much all models imply we should cut the minimum wage, if only temporarily, for small business at the very least.

Put in whatever exotic assumptions you wish, a basic model will spit out a lower optimal minimum wage for 2020-21, again for small business at the very least. This is the advice that leading Democratic economists should be offering to Biden.

From the comments, on the value of management consultants

As a retired management consultant, some views on their stated value (as stated by clients, which is not necessarily the same as “value” as seen by other observers, e.g. Douglas Adams). 1. Consultants as temps. Keep own planning staff small, hire consultants when surge capacity needed. 2. New views. Yes, the young consultants may not know your industry well. This fresh look may actually be desired. In my own experience clients oscillated between “Give me people who actually know something about my business!” and “Stop giving me people from inside my world, they just tell me what I already know!” 3. Cowardice. Client knows he must lay off 5,000, call in consultants to figure that out, blame them for it. 4. Sounding boards. Senior executives believe it or not often have no one to talk to, who is not scheming to take their job or playing other politics. Consultants play politics of course, but they are at least transparent: “If I give you advice you find valuable you will hire me again.” 5. Pollination. The client cannot go and ask 5 rival firms what they think about developments in the industry, at least not easily. If the consultants have worked for many clients in the industry, they can transfer best ideas. If you like this, you call it “dissemination of best practices;” if you don’t like it, you call it “stealing and re-selling trade secrets to rivals”. 6. Complexity. A client on its own may not want to invest in learning all it needs about AI, IOT, Bitcoin, on and on. The consultant invests in this knowledge (McKinsey’s research budget is in at least 8 digits, including opportunity costs) and can deliver it packaged up for easy access by the client.

That is from Glenn Mercer.

Covid-19 age demographics and countries

Here is an excellent document, best material I have seen on this topic so far, by the excellent Elad Gil and Shin Kim.

Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages?

There is a new NBER paper by Veronica Guerrieri, Guido Lorenzoni, Ludwig Straub, Iván Werning:

We present a theory of Keynesian supply shocks: supply shocks that trigger changes in aggregate demand larger than the shocks themselves. We argue that the economic shocks associated to the COVID-19 epidemic—shutdowns, layoffs, and firm exits—may have this feature. In one-sector economies supply shocks are never Keynesian. We show that this is a general result that extend to economies with incomplete markets and liquidity constrained consumers. In economies with multiple sectors Keynesian supply shocks are possible, under some conditions. A 50% shock that hits all sectors is not the same as a 100% shock that hits half the economy. Incomplete markets make the conditions for Keynesian supply shocks more likely to be met. Firm exit and job destruction can amplify the initial effect, aggravating the recession. We discuss the effects of various policies. Standard fiscal stimulus can be less effective than usual because the fact that some sectors are shut down mutes the Keynesian multiplier feedback. Monetary policy, as long as it is unimpeded by the zero lower bound, can have magnified effects, by preventing firm exits. Turning to optimal policy, closing down contact-intensive sectors and providing full insurance payments to affected workers can achieve the first-best allocation, despite the lower per-dollar potency of fiscal policy.

All NBER papers on Covid-19 are open access, by the way.

Is U.S. average body temperature decreasing?

In the US, the normal, oral temperature of adults is, on average, lower than the canonical 37°C established in the 19th century. We postulated that body temperature has decreased over time. Using measurements from three cohorts–the Union Army Veterans of the Civil War (N = 23,710; measurement years 1860–1940), the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I (N = 15,301; 1971–1975), and the Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (N = 150,280; 2007–2017)–we determined that mean body temperature in men and women, after adjusting for age, height, weight and, in some models date and time of day, has decreased monotonically by 0.03°C per birth decade. A similar decline within the Union Army cohort as between cohorts, makes measurement error an unlikely explanation. This substantive and continuing shift in body temperature—a marker for metabolic rate—provides a framework for understanding changes in human health and longevity over 157 years.

That is from a new paper by Protsiv, Ley, Lankester, Hastie, and Parsonnet. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Emmanuel Todd, *Lineages of Modernity*

Sadly I had to read this book on Kindle, so my usual method of saving passages and ideas by the folded page is failing me. I can tell you this is one of the most interesting (but also flawed) books I read this year, with “family structure is sticky and it determines the fate of your nation” as the basic takeaway.

Todd suggests that the United States actually has a fairly “backward” and un-evolved family structure — exogamy and individualism — not too different from that of hunter-gatherer societies. That makes us very flexible and also well-suited to handle the changing conditions of modernity. Much of the Arab world, in contrast, has a highly complex and evolved and in some ways “more advanced” family structure, involving multiple alliances, overlapping networks, and often cousin marriages. The mistake is to think of those structures as under-evolved outcomes that simply can advance a bit, “loosen up with prosperity,” and allow their respective countries to enter modernity. Rather those structures are stuck in place, and they will interact with the more physical features of globalization and liberalization in interesting and not always pleasant ways. Many of those societies will end up in untenable corners with no full liberalization anywhere in sight. Much of Todd’s book works through what the various options are here, and how they might apply to different parts of the world.

To be clear, half of this book is unsupported, or sometimes just trivial. There were several times I was tempted to just stop reading, but then it became interesting again. Todd covers a great deal of ground (the subtitle is A History of Humanity from the Stone Age to Homo Americanus), not all of it convincingly. But when he makes you think, you really feel he might be on to something.

Todd describes Germany as having a complex, multi-tiered, somewhat authoritarian family structure, and one that does not mesh well with the norms of feminism and individualism that have been entering the country. That family structure is also part of why Germany was, relative to its size, militarily so strong in the earlier part of the twentieth century. He also argues that the countries that stayed communist longer have some common features to their family structure, Cuba being the Latin American outlier in this regard.

Todd makes the strongest bullish case for Russia I have seen. He reports that TFR is back up to 1.8 after an enormous post-communist plunge, migration into the country is strongly positive, and Russia is very good at producing strong, productive women (again due to family structure). If you think human capital matters, the positives here are significant indeed.

Here is some related work by my colleagues Jonathan Schulz and Jonathan Beauchamp on cousin marriage.

You can order Todd’s book here. Recommended, though with significant caveats, mainly for lack of evidence on some of the key propositions.

The new Ben Horowitz management book

What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Own Business Culture. It is the best book on business culture in recent memory, here is one bit:

When Tom Coughlin coached the New York Giants, from 2004 to 2015, the media went crazy over a shocking rule he set: “If you are on time, you are late.” He started every meeting five minutes early and fined players one thousand dollars if they were late. I mean on time…”Players ought to be there on time, period,” he said. “If they’re on time, they’re on time. Meetings start five minutes early.”

And:

Two lessons for leaders jump out from Senghor’s experience:

-

Your own perspective on the culture is not that relevant. Your view or your executive team’s view of your culture is rarely what your employees experience.

You can pre-order the book here, due out in October.

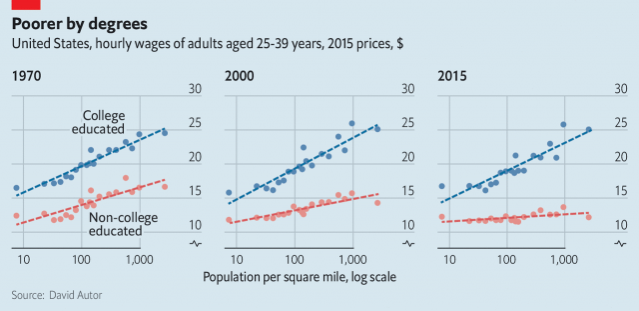

No Urban Wage Premium for Non-College Educated Workers

The Economist has a nice graph and article on the urban wage premium based on David Autor’s work. The graphs shown that in the past both college and non-college educated workers earned higher wages in more densely populated areas but today only college-educated workers experience an urban wage-premium.

Housing costs eat a large share of the college wage-premium so even college educated workers are not as better off in cities as the graphs make it appear. Autor’s point, however, is that wages for the non-college educated aren’t higher in cities so they might not move to cities even with lower housing costs. That could be true but I also suspect that the urban wage premium for the non-college educated is endogenous–firms employing these workers have moved out of the city but could move back in with lower housing and land costs.

Engagement with “fake news” on Facebook is declining

In recent years, there has been widespread concern that misinformation on social media is damaging societies and democratic institutions. In response, social media platforms have announced actions to limit the spread of false content. We measure trends in the diffusion of content from 569 fake news websites and 9,540 fake news stories on Facebook and Twitter between January 2015 and July 2018. User interactions with false content rose steadily on both Facebook and Twitter through the end of 2016. Since then, however, interactions with false content have fallen sharply on Facebook while continuing to rise on Twitter, with the ratio of Facebook engagements to Twitter shares decreasing by 60 percent. In comparison, interactions with other news, business, or culture sites have followed similar trends on both platforms. Our results suggest that the relative magnitude of the misinformation problem on Facebook has declined since its peak.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Allcott, Gentzkow, and Yu.

Twentieth-century cousin marriage rates explain more than 50 percent of variation in democracy across countries today.

That is the last sentence of the abstract in this job market paper, from Jonathan F. Schulz:

Political institutions vary widely around the world, yet the origin of this variation is not well understood. This study tests the hypothesis that the Catholic Church’s medieval marriage policies dissolved extended kin networks and thereby fostered inclusive institutions. In a difference-in-difference setting, I demonstrate that exposure to the Church predicts the formation of inclusive, self-governed commune cities before the year 1500CE. Moreover, within medieval Christian Europe,stricter regional and temporal cousin marriage prohibitions are likewise positively associated with communes. Strengthening this finding, I show that longer Church exposure predicts lower cousin marriage rates; in turn, lower cousin marriage rates predict higher civicness and more inclusive institutions today. These associations hold at the regional, ethnicity and country level. Twentieth-century cousin marriage rates explain more than 50 percent of variation in democracy across countries today.

Here is Jonathan’s (co-authored) working paper on “The origins of WEIRD psychology.“

Is innovation democracy’s unique advantage?

I say yes, though I don’t think it is easy to prove. Here is part of the abstract, from Rui Tang and Shiping Tang:

We contend that the channel of liberty‐to‐innovation is the most critical channel in which democracy holds a unique advantage over autocracy in promoting growth, especially during the stage of growth via innovation. Our theory thus predicts that democracy holds a positive but indirect effect upon growth via the channel of liberty‐to‐innovation, conditioned by the level of economic development. We then present quantitative evidence for our theory.

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.