Results for “alesina” 33 found

A simple parable on cutting government spending vs. raising taxes

Referring to Europe, here is an email (slightly edited for clarity) I sent last night to a libertarian friend:

…let’s say the private sector is so screwed up that at the margin it won’t grow, no matter what, though some going concerns hold govt.-protected monopoly power.

If govt. cuts spending by $100, that is $100 less of output and employment (admittedly may be wasteful), but still the numbers come out that way. None of those workers are reemployed.

If govt. raises taxes by $100, some of the firms with monopoly power, while their profits are now lower, still will produce roughly the same output. Neither output nor employment falls so much.

That gives you a composition difference, pretty much fully blameable on government intervention, and without requiring any belief in Keynesian economics. Govt. spending cuts are *worse* for short-run gdp than are tax increases.

I am not saying that is always the true story, but I don’t see anything in the 1990s Alesina results to convince me to believe otherwise. Europe (or rather parts thereof) is less dynamic these days. And I don’t see why libertarians are in such a hurry to dismiss that particular story.

I am not claiming that Keynesian effects have to be zero, but rather using that as a hypothetical starting point. And this is a thought experiment to raise some points about observational equivalence, not a series of empirical claims about the real world.

You also may notice that in this “model” contractionary fiscal policy lowers gdp. And while expansionary policy raises measured gdp, it doesn’t necessarily do the economy a lot of good. It’s like a hidden transfer payment with possible hysteresis benefits through the illusion of make-work, but it is hardly on its own a source of much turnaround.

Assorted links

2. One year anniversary of IHS Kosmos video, podcast, and informational site. Here is my short video on academic publishing.

3. Are puffins a cyclical asset, attracted by undervalued real exchange rates? Sadly this piece never considers an economic explanation for the phenomenon under study.

4. Is Japanese health care falling apart?

5. Alesina and Giavazzi on Italy.

6. Who are the world’s biggest employers?

7. Time inconsistent budget agreements.

8. Be very careful comparing poverty line changes over time.

Who will win the Nobel Prize in economics this year?

I see a few prime candidates:

1. Richard Thaler joint with Robert Schiller.

2. Martin Weitzman and William Nordhaus, for their work on environmental economics.

3. Three prominent econometricians of your choice, bundled.

4. Jean Tirole, possibly bundled with Oliver Hart and other game theorists/principle agent theorists. But last year the prize was in a similar field so the chances here have gone down for the time being.

5. Doug Diamond, bundled with another theorist or two of financial intermediation, such as John Geanakopolos. Bernanke probably has to wait, although that may militate against the entire idea of such a prize right now.

6. Dale Jorgenson plus ???? (Baumol?) for a productivity prize.

I see #1 or #2 as most likely, with Al Roth and Ernst Fehr also in the running. Sadly, it seems it is too late for the deserving Tullock.

In general I think Robert Barro has a good chance but I don't see him being picked so close to a financial crisis; the pick would be seen as an endorsement of Barro's negative attitude toward fiscal stimulus and I don't expect that from the Swedes. The financial crisis is a problem for Fama especially, though he is arguably the most deserving of the non-recipients. Paul Romer is another likely winner, although they may wait until rates of growth pick up in the Western world. He is still young. The Thomson-Reuters picks seem too young and for Alesina the political timing probably is not right for the same reasons as Barro.

Here is a blog post on the betting odds for the literature prize; NgŠ©gÄ© wa Thiong'o is rising on the list. Not long ago the absolute favorite was Tomas Tranströmer, who perhaps should start his own line of toys or have his name put on a school of engineering.

How should economic instruction change?

I'll transplant the links in from Mark Thoma:

Here's my response, along with responses by Alberto Alesina, Laurence Kotlikoff, Michael Pettis, Gilles Saint-Paul, Paul Seabright, Richard Baldwin, Michael Bordo, Guillermo Calvo, Tyler Cowen, Harold James, David Laibson, and Eswar Prasad [All Responses].

I realized I forgot to talk about the need for more economic history, but that is discussed by several others so at least the point got made.

One of my favorite David Brooks columns

Here is one excerpt:

In times like these, deficit spending to pump up the economy doesn’t make consumers feel more confident; it makes them feel more insecure because they see a political system out of control. Deficit spending doesn’t induce small businesspeople to hire and expand. It scares them because they conclude the growth isn’t real and they know big tax increases are on the horizon. It doesn’t make political leaders feel better either. Lacking faith that they can wisely cut the debt in some magically virtuous future, they see their nations careening to fiscal ruin.

Read the whole thing. Just about every paragraph is excerpt-worthy, for instance:

Alberto Alesina of Harvard has surveyed the history of debt reduction. He’s found that, in many cases, large and decisive deficit reduction policies were followed by increases in growth, not recessions. Countries that reduced debt viewed the future with more confidence. The political leaders who ordered the painful cuts were often returned to office. As Alesina put it in a recent paper, “in several episodes, spending cuts adopted to reduce deficits have been associated with economic expansions rather than recessions.”

This was true in Europe and the U.S. in the 1990s, and in many other cases before. In a separate study, Italian economists Francesco Giavazzi and Marco Pagano looked at the way Ireland and Denmark sharply cut debt in the 1980s. Once again, lower deficits led to higher growth.

There are, of course, ways to explain these other histories. Monetary policies, interest rates, and exchange rates were all different in many of these studied cases. The point is not that aggressive fiscal policy is always bad. The point is that there are plenty of coherent models where fiscal consolidation is better than fiscal expansion. "Lack of confidence in a nation's fiscal future" is a key condition for many of those models to hold. Is that not possibly the case today?

Modern Principles: Italian Edition

This is the cover to the Italian edition of Modern Principles of Economics which will appear early in the new year. Vedere la mano invisibile. Capire il vostro mondo!

By the way, if you are in Italy this summer Tyler will be speaking at the Festival Economia 2010 in Trento, June 3-6. Vernon Smith, Diego Gambetta, Robert Putnam, and Alberto Alesina are also among the speakers and with concerts and movies it truly is a festival of economics! Bravo!

Of course, you can find out more about the english editions of Modern Principles of Economics here (micro, macro and combined).

Where Greece went wrong

Here is another useful paper on Greek economic history. Here is one excerpt:

Rather than adopting policies to correct the macroeconomic imbalances of the Greek economy in order to restore macroeconomic stability and growth, the newly elected Socialist government further promoted policies for income redistribution and the expansion of the public sector. These policies reflected two aspects of the political and economic system of that period. First, they reflected the political priorities of the newly elected government, which was elected under a promise to the public for a radical change in the socioeconomic system. The expansion of the welfare state in the late 1970s had increased the public’s appetite for additional state transfers and for further measures to lower the gap between low- and high-income groups in the society. Second, they reflected the lack of any constraint, internal or external, in the conduct of economic policy. The debt-to-GDP ratio in 1981 was only 34.5%, despite the fiscal expansion that took place during that year. The debt-to-GDP ratio was the highest of the previous 30 years, but still at a relatively low level by world standards. Thus, the Greek government did not face any difficulties borrowing from the domestic and international markets in the early 1980s. This allowed the government to continue pursuing its expansionary policies. Moreover, the central bank lacked independence, a factor that Alesina (1988) and Cukierman, et. al., (1992) find to be inversely related to inflation. Even though the Currency Committee was officially abolished in 1982, the government continued to set the broad outlines of monetary and exchange rate policies during the 1980s. This meant that monetary policy was dominated by the need to finance fiscal expansion.

Although I still favor Greece leaving the Eurozone, we should remember they joined the currency union for a plausible reason, namely that their own monetary policy was a disaster in the making. Here's a very good post on how deeply structural the Greek problems run.

Independent Central Banks and Inflation

A number of prominent economists have signed a petition calling for Congress and the Executive Branch to reaffirm their support for and defend the independence of the Federal Reserve System." The petition is disingenuous.

The petition argues that "central bank independence has been shown to be essential for controlling inflation." "Essential," is a big exaggeration. There is evidence that more independent central banks are better at controlling inflation (e.g. Alesina and Summers 1993). Consider, however, New Zealand's central bank; it has been very successful at reducing inflation but in some ways it is one of the least independent central banks in the world precisely because (unlike in the U.S.) the governor can be fired if inflation moves outside of a target region.

Furthermore, the petition says that central bank decisions should not be "politicized." Again,this is disingenuous. Why are more independent central banks better at fighting inflation than less independent central banks? There is nothing magical about independence that makes for low-inflation. Suppose we pick someone at random and give them complete power over monetary policy. Such a central banker would be very independent but I wouldn't count on this policy resulting in much in the way of systematically lower inflation.

The primary reason that independent central banks are better at controlling inflation is that absent direct political control the default selection mechanism favors bankers, i.e. lenders, people whose interests make them more favorable towards lower inflation.

Thus, independence is a political decision that favors lenders in the decisions of monetary policy. Now, depending on the alternatives, there may be good reasons for making this choice but we should not fool ourselves into thinking that we have depoliticized money. We should not be surprised, for example, that "independent" central banks tend to make lender of last resort decisions that protect banks and bankers.

Addendum: See also Robert Higgs on the petition and Arnold Kling offers cogent comments on the closely related issue of whether the Fed should be "audited," whatever that means.

Looking for the placebo

I was invited to contribute to an Economist symposium on Olivier Blanchard's guest essay. My piece is here and here is my bottom line:

placebo idea. It is well known in the medical literature that sometimes

placebos work as well as the drugs themselves.

Here is the complete set of essays, featuring Shiller, Caballero, Alesina, Thoma, and others. Here is Bryan Caplan making a similar point about placebos.

More on Bartels

I’m a little surprised that the Bartels result is receiving so much attention because the result, in slightly different form, has long been known to political economists under the rubric of partisan business cycle theory. In a nutshell, the theory of partisan business cycles says that Democrats care more about reducing unemployment, Republicans care more about reducing inflation. Wage growth is set according to expected inflation in advance of an election. Since which party will win the election is unknown wages growth is set according to a mean of the Democrat (high) and Republican (low) expected inflation rates. If Democrats are elected they inflate and real wages fall creating a boom. If Republicans are elected they reduce inflation and real wages rise creating a bust. Notice that in PBC theory neither party creates a boom or bust it’s uncertainty which drives the result – if the winning party were known there would be neither boom nor bust.

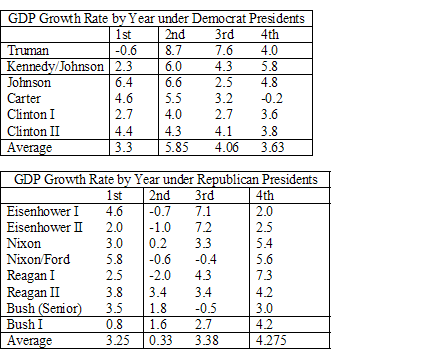

Ok, there’s plenty to question about the theory but let’s look at the data.

Notice that in the second year of just about every Democratic Presidency there is a boom. Interestingly, the boom is biggest for Truman whose reelection was highly uncertain (remember Dewey wins!) thus expected inflation would have been low and the boom big. Similarly the boom is smallest (relative to the surrounding years) for Clinton II a relatively certain reelection.

Now look at Republicans in just about every second year of a Republican Presidency there is a bust. The one major exception being Reagan II where uncertainty about the outcome was low.

It’s pretty clear that this result can explain Bartels’s result which is exactly Tyler’s point in his post. It’s equally clear that when we consider Presidents there aren’t many data points. (PBC does appear to hold somewhat in other countries).

Notice that the reason for the result, according to PBC, is sticky wages and the business cycle and not some nefarious story about taxes, oligarchies and political conspiracies.

Why the Left should learn to love liberalism

Labour-market flexibility, deregulation of the service industry,

pension reforms and greater competition in university funding is not

anti-equality. Such reforms shift financing from taxpayers to the users

themselves and, as such, tend to eliminate rents. They tend to increase

productivity by basing rewards on merit rather than on being an

insider. They tend to open up opportunities for younger workers who are

not yet well-connected. Pursuing pro-market reforms does not imply

facing a trade-off between efficiency and social justice. In this

sense, pro-market policies are “left wing”, if that means reducing the

economic privileges enjoyed by “insiders”.…If the European left wants to be able to say honestly that it fights

for the neediest members of our society, it must adopt as its battle

cry the pursuit of competition, reforms and a system based on

meritocracy.

Amen. This is from an excellent op-ed by Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavazzi writing in Vox. My only complaint is that they write as if this is new. In fact, liberalism, meaning classical liberalism, has never been conservative. It began as a movement of the left against feudalistic, conservative insiders and it remains so today.

The Power of the Family

Alesina and Giuliano report:

The structure of family relationships influences economic behavior and attitudes. We define our measure of family ties using individual responses from the World Value Survey regarding the role of the family and the love and respect that children need to have for their parents for over 70 countries. We show that strong family ties imply more reliance on the family as an economic unit which provides goods and services and less on the market and on the government for social insurance. With strong family ties home production is higher, labor force participation of women and youngsters, and geographical mobility, lower. Families are larger (higher fertility and higher family size) with strong family ties, which is consistent with the idea of the family as an important economic unit. We present evidence on cross country regressions. To assess causality we look at the behavior of second generation immigrants in the US and we employ a variable based on the grammatical rule of pronoun drop as an instrument for family ties. Our results overall indicate a significant influence of the strength of family ties on economic outcomes.

Here is the link. This topic remains understudied by economists. Biographically speaking, our political views often spring from our experience of our families and our views of what kind of family structure is acceptable. That is partly why true Russian liberals are so hard to find, and also why Russians are not obsessed with the welfare state. Libertarians tend to be family-ornery; compared to their conservative brethren, they are less willing to knuckle down and admit the morally binding power of irrational family obligations.

Addendum: Will Wilkinson has a good post on family.

The best sentence I read today

In Germany peak hour traffic on a Friday is 2 pm.

That is from Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavazzi, The Future of Europe: Reform or Decline.

The Idea Trap lasts a long time

Here is the latest by Alberto Alesina and Nicola Scheundeln:

Preferences for redistribution, as well as the generosities of welfare

states, differ significantly across countries. In this paper, we test

whether there exists a feedback process of the economic regime on

individual preferences. We exploit the "experiment" of German

separation and reunification to establish exogeneity of the economic

system. From 1945 to 1990, East Germans lived under a Communist regime

with heavy state intervention and extensive redistribution. We find

that, after German reunification, East Germans are more in favor of

redistribution and state intervention than West Germans, even after

controlling for economic incentives. This effect is especially strong

for older cohorts, who lived under Communism for a longer time period.

We further find that East Germans’ preferences converge towards those

of West Germans. We calculate that it will take one to two generations

for preferences to converge completely.

Here is Bryan Caplan on The Idea Trap, one of his best pieces.

More Nobel Prize ideas

1. Nobel prize in environmental economics to Weitzman, Nordhaus

2. Nobel prize in trade theory to Bhagwatti and Dixit

3. Nobel prize in President Bush praising to Krugman and David Brooks

4. Nobel prize in behavioral stuff to Richard Thaler

5. Nobel prize in contracts to Hart, Holmstrom, and Oliver Williamson

6. Nobel prize in development economics to Dasgupta and Deaton

7. Nobel prize in finance to Fama

8. Nobel Price in mechanism design to Milgrom, Myerson and Maskin

9. Nobel prize in family economics to Mincer and Pollak

10. Prize in Political Economy to Alesina, Persson and Tabellini

11. Prize in Modern Macro to Barro and Sargent