Results for “banerjee” 68 found

Poor Economics

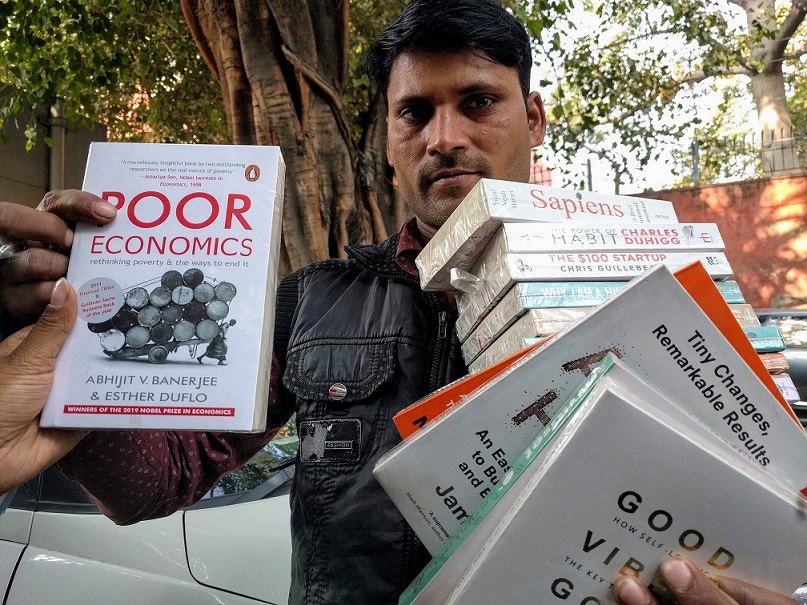

In Delhi, street hawkers will sell food, flowers, and balloons to cars paused at an intersection and, sadly, small children will dance for alms. My favorites are the book hawkers. I suspect Banerjee and Duflo would approve of my choice of both title and seller. Good price also.

Is it harder to become a top economist?

Mathis Lohaus writes to me:

Thanks for doing the Conversations. I greatly enjoyed Acemoglu, Duflo, and Banerjee in short succession after the Christmas break. Your question about “top-5 journals” and the bits about graduate training reminded of something I’ve had on my mind for a while now:

For the average PhD student, how hard is it to become a tenured economist — compared to 10, 20, 30, 40 … years ago? (And how about someone in the top 10% of talent/grit?)

Publication requirements have clearly become tougher in absolute terms. But how difficult is it to write a few “very good” papers in the first place? On twitter, people will sometimes say things like “oh, it must have been nice to get tenure back in 1997 based on 1 top article, which in turn was based on a simple regression with n = 60”. I wonder if that criticism is fair, because I imagine the learning curve for quantitative methods must have been challenging. And what about the formal models etc.? Surely those were always hard. (I vaguely remember a photo showing difficult comp exam questions…)

More broadly, early career scholars now have tons of data and inspiring research at their fingertips all the time. Also, nepotism and discrimination might be less powerful than in earlier decades…? On the other hand, you have to take into account that many more PhDs are awarded than ever before. I suspect that alone is a huge factor, but perhaps less acute if we focus only on people who “really, really want to stay in academia”.

A different way to ask the question: When would have been the best point in time to try to become an econ professor (in the USA)?

I would love to hear about your thoughts, and/or input from MR readers.

I always enjoy questions that somewhat answer themselves. I would add these points:

1. The skills of networking and finding new data sets are increasingly important, all-important you might say, at least for those in the top tier of ability/effort.

2. Fundraising matters more too, because the project might cost a lot, RCTs being the extreme case here.

3. Managing your research team matters much more, and the average size of research team for influential work is much larger. Once upon a time, three authors on a paper was considered slightly weird (the claim was one of them virtually always did nothing), now four is quite normal and the background research support is much higher as well.

Recently I was speaking to someone on the job market, wondering if he should be an academic. I said: “In the old days you spent a higher percentage of your time doing economics. Nowadays, you spend a higher percentage of your time managing a research team doing economics. You hardly do economics at all. So if you are mainly going to be a manager, why not manage for the higher rather than the lower salary?”

That was tongue in cheek of course.

On the bright side, learning today through the internet is so much easier. For instance, I find YouTube a good way to learn/refresh on new ideas in econometrics, easier than just trying to crack the final published paper.

What else?

Saturday assorted links

1. Nick Gillespie on State Capacity Libertarianism.

2. Abhijit Banerjee on coaching the poor.

3. Daniel Drezner on Iran. And further observations on Iran. And Thomas Friedman on the killing (NYT). How the kill decision was made. Last night I watched 3 Faces, a remarkable Iranian movie by Jafar Panahi.

4. New crypto journal About Nakamato. With most of the famous people in it, and more to come.

Most Popular Posts of 2019

Here are the top MR posts for 2019, as measured by landing pages. The most popular post was Tyler’s

1. How I practice at what I do

Alas, I don’t think that will help to create more Tylers. Coming in at number two was my post:

2. What is the Probability of a Nuclear War?

Other posts in the top five were 3. Pretty stunning data on dating from Tyler and my posts, 4. One of the Greatest Environmental Crimes of the 20th Century,and 5. The NYTimes is Woke.

My post on The Baumol Effect which introduced my new book Why are the Prices So Damned High (one of Mercatus’s most downloaded items ever) was number 6 and rounding out the top ten were a bunch from Tyler, including 7. Has anyone said this yet?, 8. What is wrong with social justice warriors?, 9. Reading and rabbit holes and my post Is Elon Musk Prepping for State Failure?.

Other big hits from me included

- Air Pollution Reduces IQ, a Lot (Mostly a Patrick Collison post)

- The Nobel Prize in Economic Science Goes to Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer

- Bitcoin is Less Secure than Most People Think

- Active Learning Works But Students Don’t Like It

- Sex Differences in Personality are Large and Important

Tyler had some truly great posts in the last few days of 2019 including what I thought was the post of the year (and not just on MR!) Work on these things.

Also important were:

- “What will you do to stay weird?”

- Joker

- Amazon and Taxes a Simple Primer

- Best Non-fiction books of 2019.

Happy holidays everyone!

Sunday assorted links

1. Technological progress in rock climbing.

2. Technological progress in bowling alleys, which are making a comeback (Bloomberg).

3. Duflo and Banerjee on incentives and economic policy (NYT).

Saturday assorted links

The O-Ring Model of Development

Michael Kremer’s Nobel prize (with Duflo and Banerjee) reminded me of his important paper The O-Ring Theory of Development. I also rewatched my video on this paper from Tyler’s and my online class, Development Economics. This was from our powerpoint and iPad days so there are no fancy graphics but the video holds up! Mostly because it’s a great model with lots of interesting implications not just for development but also for the structure of the US economy. See also Jason Collins on Garett Jones’s extension of the model.

Michael Kremer, Nobel laureate

To Alex’s excellent treatment I will add a short discussion of Kremer’s work on deworming (with co-authors, most of all Edward Miguel), here is one summary treatment:

Intestinal helminths—including hookworm, roundworm, whipworm, and schistosomiasis—infect more than one-quarter of the world’s population. Studies in which medical treatment is randomized at the individual level potentially doubly underestimate the benefits of treatment, missing externality benefits to the comparison group from reduced disease transmission, and therefore also underestimating benefits for the treatment group. We evaluate a Kenyan project in which school-based mass treatment with deworming drugs was randomly phased into schools, rather than to individuals, allowing estimation of overall program effects. The program reduced school absenteeism in treatment schools by one-quarter, and was far cheaper than alternative ways of boosting school participation. Deworming substantially improved health and school participation among untreated children in both treatment schools and neighboring schools, and these externalities are large enough to justify fully subsidizing treatment. Yet we do not find evidence that deworming improved academic test scores.

If you do not today have a worm, there is some chance you have Michael Kremer to thank!

With Blanchard, Kremer also has an excellent and these days somewhat neglected piece on central planning and complexity:

Under central planning, many firms relied on a single supplier for critical inputs. Transition has led to decentralized bargaining between suppliers and buyers. Under incomplete contracts or asymmetric information, bargaining may inefficiently break down, and if chains of production link many specialized producers, output will decline sharply. Mechanisms that mitigate these problems in the West, such as reputation, can only play a limited role in transition. The empirical evidence suggests that output has fallen farthest for the goods with the most complex production process, and that disorganization has been more important in the former Soviet Union than in Central Europe.

Kremer with co-authors also did excellent work on the benefits of school vouchers in Colombia. And here is Kremer’s work on teacher incentives — incentives matter! His early piece on wage inequality with Maskin, from 1996, was way ahead of its time. And don’t forget his piece on peer effects and alcohol use: many college students think the others are drinking more than in fact they are, and publicizing the lower actual level of drinking can diminish alcohol abuse problems. The Hajj has an impact on the views of its participants, and “… these results suggest that students become more empathetic with the social groups to which their roommates belong,.” link here.

And don’t forget his famous paper titled “Elephants.” Under some assumptions, the government should buy up a large stock of ivory tusks, and dump them on the market strategically, to ruin the returns of elephant speculators at just the right time. No one has ever worked through the issue before of how to stop speculation in such forbidden and undesirable commodities.

Michael Kremer has produced a truly amazing set of papers.

Esther Duflo reminiscenses

I first contacted Esther (and Abhijit) in 2006, when I wanted to write a New York Times column on their RCT work in India, specifically Hyderabad. They were both extremely welcoming of my inquiries and did everything possible to give me a chance to observe their work up close.

I ended up traveling to Hyderabad, India, and spent a whole day with their RCT program in the field. Annie Duflo, Esther’s sister, was gracious enough to travel with me around the city for an entire day, visiting the meetings where the women would show up to receive loans, and talking with the loan suppliers. Overall I was astonished at how well-organized the work was, and how sophisticated the on-the-ground implementers were. This was really work very carefully done.

Then, in 2013, seven years later, Banerjee and Duflo and co-authors Glennerster and Kinnan created a paper with the core results from the experiment, here is one version of the abstract:

This paper reports results from the randomized evaluation of a group lending microcredit program in Hyderabad, India. A lender worked in 52 randomly selected neighborhoods, leading to an 8.4 percentage point increase in takeup of microcredit. Small business investment and profits of pre-existing businesses increased, but consumption did not significantly increase. Durable goods expenditure increased, while “temptation goods” expenditure declined. We found no significant changes in health, education, or women’s empowerment. Two years later, after control areas had gained access to microcredit but households in treatment area had borrowed for longer and in larger amounts, very few significant differences persist.

Along with some (broadly consistent) results from Dean Karlan, this became one of the definitive papers on the effects of micro-credit. It meant that micro-credit is OK, but not the cure for poverty. That had a big subsequent impact on both policy and philanthropy.

You might have thought they would rest there, but no, they kept on looking at the data more deeply and over additional years, hoping to learn yet more from the experiment. And just this last week, a new paper came out, modifying the earlier results, based on more years of data. Here is the new abstract and paper (with Breza and Kinnan):

Can microcredit help unlock a poverty trap for some people by putting their businesses on a different trajectory? Could the small microcredit treatment effects often found for the average household mask important heterogeneity? In Hyderabad, India, we find that “gung ho entrepreneurs” (GEs), households who were already running a business before microfinance entered, show persistent benefits that increase over time. Six years later, the treated GEs own businesses that have 35% more assets and generate double the revenues as those in control neighborhoods. We find almost no effects on non-GE households. A model of technology choice in which talented entrepreneurs can access either a diminishing-returns technology, or a more productive technology with a fixed cost, generates dynamics matching the data. These results show that heterogeneity in entrepreneurial ability is important and persistent. For talented but low-wealth entrepreneurs, short-term access to credit can indeed facilitate escape from a poverty trap.

That is a pretty stunning extension of the original results, bravo to all hands involved! Rust never sleeps, and in the hands of Banerjee and Duflo, neither does science.

*Good Economics for Hard Times*

Yes, that is the new and forthcoming book by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, and it tells you what they really think about everything. Everything in mainstream economic policy debate, at least.

So far I have read only the first chapter, on migration, but I found it informative, highly readable, and (unlike many other popular books) subtle. I am excited to read the rest of the book, in the meantime here is one short excerpt:

Mahesh found these would-be [Nepali] migrants were in fact somewhat overoptimistic about their earnings prospects. Specifically, they overestimated their earning potential by around 25 percent, which could be for any number of reasons, including the possibility the recruiters who go to them with job offers lie to them. But the really big mistake they made was that they vastly overestimated the chance of dying while they were abroad. A typical candidate for migration thought that out of a thousand migrants, over a two-year stint, about ten would come back in a box. The reality is just 1.3.

Here is the table of contents:

1. MEGA: Make Economics Great Again

2. From the Mouth of the Shark

3. The Pains from Trade

4. Likes, Wants and Needs

5. The End of Growth?

6. In Hot Water

7. Player Piano

8. Legit.gov

9. Cash and Care

Due out November 12, you can pre-order here.

Who will win the Nobel Prize in economics this year?

I’ve never once gotten it right, at least not for exact timing, so my apologies to anyone I pick (sorry Bill Baumol!). Nonetheless this year I am in for Esther Duflo and Abihijit Banerjee, possibly with Michael Kremer, for randomized control trials in development economics.

Maybe they are too young, as Tim Harford points out, so my back-up pick remains an environmental prize for Bill Nordhaus, Partha Dasgupta, and Marty Weitzman.

What do you all predict?

Many Indian children can use math to solve market problems, but not school problems

The untapped math skills of working children in India: Evidence, possible explanations, and implications (with A. V. Banerjee, S. Bhattacharjee & R. Chattopadhyay)

It has been widely documented that many children in India lack basic arithmetic skills, as measured by their capacity to solve subtraction and division problems. We surveyed children working in informal markets in Kolkata, West Bengal, and confirmed that most were unable to solve arithmetic problems as typically presented in school. However, we also found that they were able to perform similar operations when framed as market transactions. This discrepancy was not explained by children’s ability to memorize prices and quantities in market transactions, assistance from others at their shops, reliance on calculation aids, or reading and writing skills. In fact, many children could solve hypothetical transactions of goods that they did not sell. Our results suggest that these children have arithmetic skills that are untapped by the school system.

Sourced here.

Does Diversity Reduce Freedom or Growth?

The founding father of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, credits ‘social discipline’ for the phenomenal economic rise of his country (Sen, 1999). Countries such as Singapore apparently demonstrate that autocratic measures are probably necessary, particularly in culturally fractionalized societies for creating the social stability necessary for economic growth (Colletta et al., 2001). Such thinking informs the so-called “Asian model” (Diamond, 2008).1 Recent studies, particularly in economics, support the logic (Alesina et al., 2006 and Easterly et al., 2006). According to these scholars, the more congruent territorial borders are with nationality, the better the chances for good economic policy to appear endogenously from within these societies because social cohesion determines good institutions and policies for development (Banerjee et al., 2005 and Easterly, 2006b). This paper addresses the question of whether or not social diversity hampers the adoption of sound economic policies, including institutions that promote property rights and the rule of law. We also examine whether democracy conditions diversity’s effect on sound economic management, defined as economic freedom, because the index of economic freedom is strongly associated with higher growth and is endorsed by proponents of the ‘diversity deficit’ argument (Easterly, 2006a).2

…Using several measures of diversity, we find that higher levels of ethno-linguistic and cultural fractionalization are conditioned positively on higher economic growth by an index of economic freedom, which is often heralded as a good measure of sound economic management. High diversity in turn is associated with higher levels of economic freedom. We do not find any evidence to suggest that high diversity hampers change towards greater economic freedom and institutions supporting liberal policies.

Paper here. The data is a panel from 116 countries covering 1980–2012 so this doesn’t rule out a negative long-run effect but it is prima facie evidence that diversity need not reduce freedom or growth.

Who will win the Nobel Prize in Economics this coming Monday?

I’ve never once nailed the timing, but I have two predictions.

The first is William Baumol, who is I believe ninety-four years old. His cost-disease hypothesis is very important for understanding the productivity slowdown, see this recent empirical update. Oddly, the hypothesis is most likely false for the sector where Baumol pushed it hardest — music and the arts.

Baumol has many other contributions, but the next most significant is probably his theory of contestable markets, plus his writings on entrepreneurship.

The other option is a joint prize for environmental economics, perhaps to William Nordhaus, Partha Dasgupta, and Martin Weitzman. A prize in that direction is long overdue.

The “Web of Science” predicts Lazear, Blanchard, or Marc Melitz, based on citation counts. Other reasonable possibilities include Robert Barro, Paul Romer, Banerjee and Duflo and Kremer (joint?), David Hendry, Diamond and Dybvig, and Bernanke, Woodford, and Svensson, arguably joint. I still am of the opinion that Martin Feldstein is deserving, don’t forget he did empirical public finance, was a pioneer in health care economics, and built the NBER. For a dark horse pick, how about Joseph Newhouse (RCTs and the Rand health care study)?

There are other options — what is your prediction?