Results for “katrina” 50 found

Houston Flooding and Zoning and Development

A lot of nonsense has been written about the causes of flooding in Houston. Anti-immigration people blame immigration. Anti-development people blame development. Anti-Trump people blame Republicans.

The truth, however, is that Houston has flooded regularly since it was founded. Moreover, unlike Katrina, the flood systems have mostly worked as they are supposed to–diverting water to the highways, for example. The problem has been that there is just a lot of water.

In a superb post, Phil Magness has the details. From here on in this is Magness. I won’t indent.

————

We’ve seen a flurry of commentators in the past few days attributing Houston’s flooding to a litany of pet political causes. Aside from the normal carping about “climate change”… several pundits and journalists have opportunistically seized upon Houston’s famously lax zoning and land use regulations to blame Harvey’s destruction on “sprawl” and call for “SmartGrowth” policies that restrict and heavily regulate future construction in the city.

According to this argument, Harvey’s floods are a byproduct of unrestricted suburban development in the north and west of the city at the expense of prairies that would supposedly absorb rainwater at sufficient rates to prevent natural disasters and that supposedly served this purpose “naturally” in the past.

There are multiple problems with this line of argument that suggest it is rooted in naked political opportunism rather than actual concern for Houston’s flooding problems.

First, as we’ve established in the preceding history lesson, flooding has been a regular feature of Houston’s landscape since the beginning of recorded history in the region. And catastrophic flooding – including multiple storms in the 19th century and the well-documented flood of December 1935 – predates any of the “sprawl” that has provoked these armchair urban designers’ ire.

Second, the flooding we saw in Harvey is largely a result of creeks and bayous backlogging and spilling over their banks as more water rushes in from upstream. While parking lot and roadway runoff from “sprawl” certainly makes its way into these streams, it is hardly the source of the problem. The slow-moving and windy Brazos river reached record levels as a result of Harvey and spilled over its banks, despite being nowhere near the city’s “sprawl.” The mostly-rural prairie along Interstate 10 to the extreme west of the city recorded some of the worst flooding in terms of water volume due to the Brazos overflow, although fortunately property damage here will be much lower due to being rural.

Third, the very notion that Houston is a giant concrete-laden water retention pond is itself a pernicious myth peddled by unscrupulous urban planning activists and media outlets. In total acres, Houston has more parkland and green space than any other large city in America and ranks third overall to San Diego in park acreage per capita.*

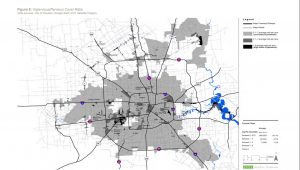

But even more telling is a 2011 study by the Houston-Galveston Area Council that actually measured the ratio of impervious-to-pervious land cover within the city limits (basically the amount of water-blocking concrete vs. water-absorbing green land). The study used an index scale to measure water-absorption land uses. A low score (defined as less than 2.0 on the scale) indicates a high presence of green relative to concrete. A high score (defined as greater than 5.0) indicates high concrete and low levels of greenery and other water-absorbing cover. The result are in the map below, showing the city limits. Gray corresponds to high levels of pervious surfaces (or greenery). Black corresponds to high impervious surface use (basically either concrete or lakes that collect runoff). As the map shows, over 90% of the land in the city limits is gray, indicating more greenery and higher water absorption. Although they did not measure unincorporated Harris County, it also tends to be substantially less dense than the city itself.

Does this mean that impervious land uses are not a problem and do not contribute to floods in any way? No. But to cite them as a principle cause of the destruction witnessed in Harvey is purely a political move aimed at generating support for a long list of intrusive regulatory policies.

Houston’s flood problems are a distinctive feature of its topography and geography, and they long predate any “sprawl.” While steps have been taken over the years to mitigate them and reduce the severity of flooding, a rare but catastrophic event will unavoidably overwhelm even the most sophisticated flood control systems. Harvey was one such event – certainly the highest floodwater event to hit Houston in over 80 years, and possibly the worst deluge in its recorded history. But it is entirely consistent with almost 2 centuries of recorded historical patterns. In the grander scheme of causes for Harvey’s flooding, “sprawl” does not even meaningfully register.

Read the whole thing for more historical background.

* Earlier version said second which was a typo as source reports third; other sources can differ depending on year and what exactly is counted.

Facts about flood insurance

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) owes $24.6 billion to the Treasury. Most of it covered claims from Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and floods in 2016, the program’s third most severe loss-year on record with losses exceeding $4 billion, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which manages it.

The NFIP was extended 17 times between 2008 and 2012 and lapsed four times in that period. A 2012 law extended the program to September.

The only source of flood insurance for most Americans, it will be in place for homeowners and businesses in Harvey’s path along the central Texas coast.

But Harvey-related claims covered under the program could push it deeper into the red and possibly toward its borrowing limit of just over $30 billion, said Steve Ellis, vice president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, a nonpartisan budget watchdog in Washington, D.C.

Federal law requires that homes in flood-risk areas have flood insurance before a mortgage can be completed. The program is the only flood insurance available to the vast majority of Americans, although a small market for private flood insurance is sprouting in flood-prone states such as Florida.

Here is the article. Note the Trump administration previously was pushing a plan to cut the insurance to pay for The Wall. I do see a case for doing without a federal role for this insurance, but the benefits there come ex ante, not from yanking it away ex post.

Do America’s poor move around enough?

Eric Chyn, from the University of Michigan, has an interesting job market paper on this topic., which suddenly is being debated again. The title is “Moved to Opportunity: The Long-Run Effect of Public Housing Demolition on Labor Market Outcomes of Children.” Here is the abstract:

This paper provides new evidence on the effects of moving out of disadvantaged neighborhoods on the long-run economic outcomes of children. My empirical strategy is based on public housing demolitions in Chicago which forced households to relocate to private market housing using vouchers. Specifically, I compare adult outcomes of children displaced by demolition to their peers who lived in nearby public housing that was not demolished. Displaced children are 9 percent more likely to be employed and earn 16 percent more as adults. These results contrast with the Moving-to-Opportunity (MTO) relocation study, which detected effects only for children who were young when their families moved. To explore this discrepancy, this paper also examines a housing voucher lottery program (similar to MTO) conducted in Chicago. I find no measurable impact on labor market outcomes for children in households that won vouchers. The contrast between the lottery and demolition estimates remains even after re-weighting the demolition sample to adjust for differences in observed characteristics. Overall, this evidence suggests lottery volunteers are negatively selected on the magnitude of their children’s gains from relocation. This implies that moving from disadvantaged neighborhoods may have substantially larger impact on children than what is suggested by results from voucher experiments where parents elect to participate.

Justin Fox argues that moving is hard, but basically more of the poor should move, at least using standard economic metrics for family well-being. Results from the Katrina natural experiment indicate the same. Ultimately we wish to protect people, not places per se.

Very good points on FEMA

We’ve nationalized so many of the events over the last few decades that the federal government is involved in virtually every disaster that happens. And that’s not the way it’s supposed to be. It stresses FEMA unnecessarily. And it allows states to shift costs from themselves to other states, while defunding their own emergency management because Uncle Sam is going to pay. That’s not good for anyone.

When FEMA’s operational tempo is 100-plus disasters a year, it’s always having to do stuff. There’s not enough time to truly prepare for a catastrophic event. Time is a finite quantity. And when you’re spending time and money on 100-plus declarations, or over 200 last year, that taxes the system. It takes away time you could be spending getting ready for the big stuff.

Nobody is taking the position, that I know of, saying get rid of FEMA, the federal government should have no role responding to disasters. The position is, no no, we need to save FEMA and the Federal Government for the big stuff: Sandy, Katrina, Northridge. But states should be charged to take care of the other, more routine stuff that happens every year. There are always going to be Tornadoes in Oklahoma and Arkansas. There are always going to be floods in northwest Ohio and Iowa. There are always to be snowstorms in the Northeast. There are always going to be rain storms, fires in Colorado. They happen every year. There’s no surprise here. And they don’t have national or regional implications, economically or otherwise. If they do, that’s a different question.

Read the whole thing.

The Big Easy’s School Revolution

Interesting op-ed in the Washington Post on schools in New Orleans.

…the levees broke and the city was devastated, and out of that destruction came the need to build a new system, one that today is accompanied by buoyant optimism. Since 2006, New Orleans students have halved the achievement gap with their state counterparts. They are on track to, in the next five years, make this the first urban city in the country to exceed its state’s average test scores. The share of students proficient on state tests rose from 35 percent in 2005 to 56 percent in 2011; 40 percent of students attended schools identified by the state as “academically unacceptable” in 2011, down from 78 percent in 2005.

….Most of the buzz about the city’s reforms focuses on the banishment of organized labor and the proliferation of charter schools, which enroll nearly 80 percent of public school students, up from 1.5 percent pre-Katrina. But what really distinguishes New Orleans is how government has redefined its role in education: stepping back from directly running schools and empowering educators to make the decisions about hours, curriculum and school culture that best drive student learning. Now, state and school-district officials mostly regulate and monitor — setting standards, ensuring equity and closing failing schools. Instead of a traditional school system, there is a system of schools in what officials liken to a fenced-in free market. Families have more choice about where their children can best succeed, they say, and educators have more opportunity to choose a school that best aligns with their approach.

The population of New Orleans changed pre and post-Katrina so it’s difficult to compare pre and post-Katrina test scores; although given the state of the schools pre-Katrina it’s hard to believe that the schools have not greatly improved. What really drives innovation, however, is not a simple substitution of private for public but a system substitution of competition for monopoly. The key therefore is to expand charters and voucher programs.

The state of Louisiana just passed a voucher program that although limited to poor and middle class students in failing schools will offer as many as 380,000 vouchers to be used at private schools or apprenticeships. Indiana has passed a potentially even larger program that would make about 500,000 students voucher-eligible. Keep in mind that at present there are 50 million public school students and only 220,000 voucher students nationwide.

My ideal program would fund students not schools and would make vouchers available to all students on a non-discriminatory basis. We are far from that ideal but we are slowly moving in the right direction. Charters and the expansion of voucher programs around the country are starting to bring more competition, dynamism and evolutionary experimentation to the field of education.

Assorted links

What I’ve been reading

1. The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to the Sports Guy, by Bill Simmons. Could this be the best 736 pp. book on the diversity of human talent ever written? It starts slow but eventually picks up steam. It's also devastatingly funny. That said, if you don't know a lot about the NBA, it is incomprehensible. (I could not, for instance, understand the section of Dolph Schayes because that was not the NBA I know.) In the historical pantheon, he picks David Thompson, Bernard King, and Allen Iverson as underrated. The 1986 Boston Celtics are the best team ever, he argues. And so on. I found this more riveting than almost anything else I read and yes I think it is very much a work of social science, albeit in hermetic form.

2. Paul Auster, Invisible. Auster is back in top form. The French, of course, think of him as a deeper writer than do most of his American critics and readers. Is he more like Hitchcock (also appreciated early on by the French) or more like Starsky and Hutch? Read this book and decide. As usual, the truth lies somewhere in between.

3. Delirious New Orleans: Manifesto for an Extraordinary American City, by Steven Verderber. An excellent photo-essay on all the marvelous signs and small architectural wonders trashed by Hurricane Katrina. This book goes micro, not macro, and it catalogs a now-disappearing America from the age which I find most precious in our history.

4. Derrida, an Egyptian, by Peter Sloterdijk. I'm spending some of next summer in Berlin so I've been trying to catch up on what they're reading over there. (Any recommendations?) On every page it feels as if Sloterdijk is intelligent, yet I came away empty-handed and feeling like a frustrated Robin Hanson ("why doesn't he just come right out and say what he means?). No way should you buy the hardcover for $45.00, in return for 73 pp. of actual text. Ultimately he's writing about the boxes, not writing about the world. Yet at least three Germans loved it.

What I’ve been reading

1. The Idea of Justice, by Amartya Sen. This book is 415 pages of intelligent Sen-isms. Key themes are the importance of public reasoning, the plurality of reasons, and the possibility of an impartial approach to major ethical questions. We also learn that in 1938 Wittgenstein was determined to go to Vienna and give Hitler a stern lecture; he had to be talked out of it. At the end of it all I was more rather than less confused about what impartiality means. I don't blame that on Sen, but that says more about the book than any particular comment which I might make. It's a very good introduction to Sen's ethical thought but it's ultimately the Wittgenstein anecdote which sticks with me.

2. Await Your Reply, by Dan Chaon. This tripartite mystery about reinventing yourself has received rave reviews and Amazon readers are strongly positive. I read about one hundred pages and thought it was ably done but of no real substance.

3. How to Make Love to Adrian Colesberry, by Adrian Colesberry. My god this book is sick and I feel bad even telling you about it. It's exactly what the title promises and it has no business being discussed on a family-oriented economics blog. The language is explicit and the content is disgusting. It's also brilliant, funny, and unique. How often do I see a new approach to what a book can be? Once you get past the language and topic, it's actually about narcissism, why empathy is scarce, how we form self-images, how men classify and remember their pasts, and why management fad books are absurd.

4. A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, by Rebecca Solnit. For many people

this may be a good book but I could not read far into it. The main

thesis is quite interesting, namely that people forms immediate islands

of community and cooperation during very trying times. The examples

include the San Francisco and Mexico City earthquakes, 9/11, and

Hurricane Katrina. But I found the ratio of information to page was

too low for my admittedly extreme tastes.

Here is an interesting bit on how emergencies inspire crowd cooperation, not panic.

5. Das Museum der Unschuld, by Orhan Pamuk. That's The Museum of Innocence in English, out in late October, but I found the German-language version in Stockholm. It's in his "Istanbul nostalgic" mode rather than his "I'm trying to be like Italo Calvino" style and it promises to be one of his very best books.

Levee calculations

I can’t track down the original source here, but it sounds broadly consistent with other things I’ve read:

Under the 100-year standard…experts say that every house being rebuilt in New Orleans has a

26 percent chance of being flooded again over a 30-year mortgage; and

every child born in New Orleans would have nearly a 60 percent chance

of seeing a major flood in his or her life…At the same time, the corps

has run into funding problems, lawsuits, a tangle of local interests

and engineering difficulties — all of which has led to delays in

getting the promised work done.An initial

September 2010 target to complete the $14.8 billion in post-Katrina

work has slipped to mid-2011. Then last September, an Army audit found

84 percent of work behind schedule because of engineering complexities,

environmental provisos and real estate transactions. The report added

that costs would likely soar. A more recent

analysis shows the start of 84 of 156 projects was delayed — 15 of

them by six months or more. Meanwhile, a critical analysis of what it

would take to build even stronger protection — 500-year-type levees —

was supposed to be done last December but remains unfinished.On the road to recovery, the

agency has installed faulty drainage pumps, used outdated measurements,

issued incorrect data, unearthed critical flaws, made conflicting

statements about flood risk and flunked reviews by the National

Research Council.

When it comes to storm protection and urban reconstruction, "halfway" is not a good solution. There could have been a real rebuilding and protection, or the price signals from insurance companies could have been allowed to shrink the city more fundamentally than what happened. Here is a relevant study.

Spot the Contradiction

Daniel Gross’s review of Sachs’ Common Wealth was bizarre. Consider this:

Even congenital optimists have good reason to suspect that this time

the prophets of economic doom may be on point, with the advent of

seemingly unstoppable developments like….the explosive growth of China and India.

Huh? What kind of upside down logic makes high growth rates proof of economic doom? Proving this was no idle slip Gross goes on to say:

Things are different today, [Sachs] writes, because of four trends: human

pressure on the earth, a dangerous rise in population, extreme poverty

and a political climate characterized by “cynicism, defeatism and

outdated institutions.” These pressures will increase as the developing

world inexorably catches up to the developed world. (emphasis added)

Silly me, I thought rising life expectancy, increasing wealth, and lower world inequality, which is what it means to say that the developing world inexorably catches up to the developed world, was a good thing. And then there is this:

The combination of climate change and a rapidly growing population

clustering in coastal urban zones will set the stage for many Katrinas,

not to mention “a global epidemic of obesity, cardiovascular disease

and adult-onset diabetes.”

Ok, climate change will create problems but how clueless do you have to be not to understand that a large fraction of the world’s people would love to live long enough to die from obesity and other diseases of wealth?

Don’t misunderstand, I know that growth brings problems. My dispute with Gross is not that he thinks the glass is half-empty and I think it is half-full; my dispute is that Gross thinks the fuller the glass gets the more empty it becomes.

Addendum: Dan Gross writes to say that he was summarizing Sachs’ argument. Point noted.

The Storm

The storm ravaged the city’s architecture and infrastructure, took

hundreds of lives, exiled hundreds of thousands of residents. But it

also destroyed, or enabled the destruction of, the city’s public-school

system–an outcome many New Orleanians saw as deliverance….The floodwaters, so the talk went, had washed this befouled slate

clean–had offered, in a state official’s words, a “once-in-a-lifetime

opportunity to reinvent public education.” In due course, that

opportunity was taken:…Stripped of

most of its domain and financing, the Orleans Parish School Board fired

all 7,500 of its teachers and support staff, effectively breaking the

teachers’ union. And the Bush administration stepped in with millions

of dollars for the expansion of charter schools–publicly financed but

independently run schools that answer to their own boards. The result

was the fastest makeover of an urban school system in American history.

That’s from The Atlantic just over a year ago. Guess what? It’s working. The storm is coming.

Should the Fed have a consumer protection function?

I’m starting to wonder if the answer should be "no." Say you’re on the left and you think that banks have screwed over borrowers and that remedying or preventing this injustice should be a top priority. The Fed is not the place to look to. Barney Frank was exaggerating when he said: "If I was going to list the top 87 entities in Washington in order of

the history of their efforts on consumer protection, the Fed would not

make it," but he said that for a reason. Most of all, the Fed looks after the stability of the banking system, and the macroeconomy, which in my view is how it should be.

From a market-oriented point of view, the case for a Fed role in consumer protection is simply that the agency is better informed and more competent than Congress or the executive branch, not to mention more insulated from political pressure. But that means — as we are seeing today — that Congress will not think the Fed is doing a good job when it comes to consumer protection. The Fed ends up politicized, and under fire, when it should instead be free to pursue its central mission of maintaining macro stability. It might be better to let some other regulatory agency go ahead and make the politically-demanded mistakes here. We don’t want Congress to get into the habit of thinking it can tell the Fed what to do.

How many Representatives are willing to stand up and say: "Voters, I feel your pain, but your behavior was stupid and possibly even fraudulent"?

Have you noticed that significant segments of the press seem to be turning against the Fed? We live in dangerous times, and it is unfortunate that the subprime crisis exploded in an election year.

I was surprised by Daniel Gross’s piece comparing Bernanke’s Fed to FEMA during Katrina, linked to directly above. Other than "report the problem earlier," the key question is what Bernanke’s Fed should have done differently. It would be better to focus on that, but of course that’s a much harder question to answer. A replacement for Michael Brown — even drawn randomly from a pool of CEOs or regulators — would likely be far higher in quality, a replacement for Bernanke would likely be far lower in quality, and that’s more important than any of the supposed parallels.

Tyler Cowen gets mean and mad

I’ve now done a full review of Naomi Klein:

Most of the book is a

button-pressing, emotionally laden, whirlwind tour of global events

over the last 30 years: Katrina, the invasion of Iraq, torture in Chile,

the massacre in Tiananmen Square, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and

the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The book offers not so much

an argument but rather a Dadaesque juxtaposition of themes and

supposedly parallel developments in the global market. Above the

excited recitation stands Milton Friedman as the überdemon of the march

toward global tyranny and squalor…Often Ms. Klein’s proffered

connections are so impressionistic and so reliant on a smarmy wink to

the knowing that it is impossible to present them, much less critique

them, in the short space of a book review…Ms. Klein also tellingly remarked, "I believe people believe their own bullshit. Ideology can be a great enabler for greed."

When it comes to the best-selling "Shock Doctrine," that is perhaps the bottom line on what Klein herself has been up to.

Here is the full review; just imagine if I hadn’t liked the book!

Every claim is wrong

I wondered whether that can be said of Naomi Klein’s new The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Still, at some fundamental level I liked this book. Perhaps I still had the Greenspan memoir too fresh in my mind, but at least this text is alive. Yes she refuses to admit that Chilean reforms, however horrible the accompanying atrocities, did represent a success for market economics. Yes she misstates the role of Milton Friedman in just about everything. Yes she suggests that black children in New Orleans, pre-Katrina, enjoyed equality of educational opportunity. Yes she is naive enough to think that we need only put the good people in power. Yes she repeats many timeworn fallacies about Halliburton. Yes there is a senseless conflation of torture, Iraq, and the Coase Theorem. And so on.

Still, at the heart of this book she pinpoints the discomfort that free market advocates have with democracy. You can go the non-democratic route, you can claim that markets should stand above democracy, or you can reinterpret libertarian ideas as a general framework for social analysis and a program for gradualist democratic reform. Either way, for all her mistakes, Klein has yet to lose this debate.

An exchange about health care

Charles W. Tidd, Jr., Newtown, Conn.: Your column today

continues to avoid a central issue: a great number of Americans do not

trust the government with their health care. This mistrust is not the

result of television ads by insurance companies but follows from

increasingly frequent routine encounters with the government: waiting

for a passport, figuring out the tax law, having an intelligent

conversation with someone at the DMV, listening to the news – Hurricane

Katrina, the federal prosecutors, the pardons by both Clinton and Bush,

immigration. The list goes on and on.Why in the world do you want to trust the nation’s health care to the government? He who pays the piper calls the tune.

I write you because there is no question that our health system

needs to be fixed, but until the issue of public mistrust of government

is addressed, any sort of universal health care will be shunned by many

people.Paul Krugman:: Do people really distrust the government? I

think we have this program called Medicare, which most people seem to

like. On the other hand, maybe people don’t know that it’s the

government: former Sen. John Breaux was famously accosted by a

constituent demanding that he not let the government get its hands on

Medicare.

Here is the link.

People like Medicare because it pays some of the bill, while keeping interference in the medical process to an apparent minimum; admittedly non-interference is in part illusory because the indirect effects of Medicare (e.g., it drives up prices) have become enormous. Almost all government payments of this kind are popular, whether or not the programs are a good use of scarce resources. People are looking to get something from their costly government, and not necessarily because they trust it.

As Medicare expenditures rise, this illusion of non-interference will become much harder to maintain and indeed Medicare itself may become less popular. I am always curious to hear — from single-payer proponents — which interest groups they think will have a decisive say over the system, and how those interest groups differ in America vs. Western Europe. That is one reason why we cannot simply replicate the VA approach writ large, or for that matter the French system. For a sobering wake-up call, compare the flood defense policies of the Netherlands to, say, Louisiana.