Results for “labor mobility” 73 found

Our growing mobility

How much territory do you move through on a typical day? Jesse Ausubel writes:

US per capita mobility has increased 2.7% per year, with walking included. Excluding walking, Americans have increased their mobility 4.6% each year since 1880. The French have increased their mobility about 4% per year since 1800.

Most of all, driving has been replacing movement on foot. Follow this link and scroll down for the illustrative graph and the exact figures. Ausubel believes that in the future people will cover hundreds of kilometers every day, on average, you can think of him as the Julian Simon on transportation economics. In his view people are often willing to travel up to 60 or 70 minutes per day, but they don’t like to go beyond this figure. Yet transportation becomes ever easier and more rapid. He is bullish on magnetic levitation trains, and much of the future improvement may come from airplanes:

During the past 50 years passenger kilometers for planes have increased by a factor of 50. Air has increased total mobility per capita 10% in Europe and 30% in the United States since 1950. A growth of 2.7% per year in passenger km and of the air share of the travel market in accord with the logistic substitution model brings roughly a 20-fold increase for planes (or their equivalents) in the next 50 years for the United States and even steeper elsewhere.

And how is this for optimism?

By the year 2100, per capita incomes in the developed countries could be very high. A 2% growth rate, certainly much less than governments, central banks, industries, and laborers aspire to achieve, would bring an average American’s annual income to $200,000.

And this?

Staying within present laws, a 2.7% per year growth means doubling of mobility in 25 years and 16 times in a century.

This is almost enough to make you forget about the irresponsible fiscal policy of the Bush Administration.

Thanks for Gregg Easterbrook’s The Progress Paradox for the pointer to Ausubel’s work.

Oddly we travel as much as we do, in part, because we love home so much. Did you know that sixty percent of all European flights involve a return flight on the same day? We can go far, but the pull of home is indeed strong.

The minimum wage and migration decisions

This paper investigates the local labor supply effects of changes to the minimum wage by examining the response of low-skilled immigrants’ location decisions. Canonical models emphasize the importance of labor mobility when evaluating the employment effects of the minimum wage; yet few studies address this outcome directly. Low-skilled immigrant populations shift toward labor markets with stagnant minimum wages, and this result is robust to a number of alternative interpretations. This mobility provides behavior-based evidence in favor of a non-trivial negative employment effect of the minimum wage. Further, it reduces the estimated demand elasticity using teens; employment losses among native teens are substantially larger in states that have historically attracted few immigrant residents.

That is from a 2014 paper by Brian C. Cadena, and here is Jorge Pérez Pérez:

I find that areas in which the minimum wage increases receive fewer low-wage commuters. A 10 percent increase in the minimum wage reduces the inflow of low-wage commuters by about 3 percent.

And here is one bit from a research paper by Terra McKinnish:

Low wage workers responded by commuting out of states that increased their minimum wage.

Via the excellent Jonathan Meer, you don’t hear about this evidence as much as you should.

Words of wisdom

Lant Pritchett’s new working paper, “Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct Assistance, and Economic Growth” should be required reading for every Effective Altruist. Bottom line: Virtually all poverty reduction comes from economic growth and migration – not redistribution or philanthropy.

That is from Bryan Caplan.

Which social groups and classes should fear higher price inflation?

Paul Krugman considers who is helped and hurt by higher rates of price inflation, and he sees the big losers as the wealthy oligarchs (and see his column today here). In contrast, I see the big losers as those with protected service sectors jobs who do not wish to have their contracts reset. If you are a schoolteacher, a nominal wage cut is likely to mean a real wage cut because you don’t have the power to renegotiate into a deal as good as the one you started with. The declining labor mobility of the United States in general means that workers are more vulnerable to higher rates of price inflation. A guy living in Cleveland who plans on leaving for Houston is probably less worried about nominal variables, because he will be doing a new contract negotiation anyway.

We all know that inflation is extremely unpopular with voters. We also observe that inflation remains extremely unpopular in a variety of northern European economies, which typically have more egalitarian distributions of income (though not always wealth) than does the United States. In any case the top 0.1 percent in those countries has less wealth per capita than in the U.S. and, at least according to progressives, less political influence too.

Of course the ability of inflation to erode rents is one of its virtues. The super-wealthy are often earning rents, but typically those rents are structured to be relatively robust to changes in nominal variables. For instance the rent might take the form of IP rights, or resource ownership rights. Simple loans of money, as we find in traditional creditor-debtor relationships, just aren’t monopolizable enough or profitable enough to be a major source of riches for the most wealthy.

I was puzzled by this comment on Krugman’s:

But there is one small but influential group that is in fact hurt by financial repression

which is just like what Hitler did to the Jews: again, the 0.1 percent.

People that wealthy can put their money into hedge funds, private equity, private capital pools, and the like. Of course there is risk involved but they have a chance as good as anyone to earn the highest rates of return prevailing in an economy, through creative uses of equity and on top of that very good accountants and tax lawyers. The very wealthy also have the greatest ability to hedge against inflation using derivatives and commodities, if they do desire.

In other contexts, Krugman (correctly) stresses that price inflation lowers the real exchange rate of a country (and thus is not neutral, supporting the view that nominal variables really do matter). So one big group of gainers from domestic inflation are those who invest lots of money overseas, wait for some inflation, and eventually convert their foreign currency holdings back into dollars for a very high net rate of return.

Which group of people might that be? The super wealthy of course. (This internationalization of returns for the super wealthy, by the way, is one big difference between current times and the 1970s.)

I am not suggesting that the very wealthy are out there pushing for higher inflation. But they are much more protected against such inflation than Krugman’s analysis suggests, and the middle class in protected service sector jobs is more vulnerable than is usually recognized. There is a reason why 4-6% price inflation has become the new third rail of American politics.

Addendum: Here are some related comments from Brad DeLong. I understand the very wealthy as believing (rightly or wrongly) that higher rates of price inflation increase economic uncertainty without providing much in the way of benefit for the real economy. So, given that belief, why should they favor higher price inflation? Since the status quo is based on low rates of price inflation, a switch to higher inflation would in fact disrupt markets (for better or worse), which would send a kind of self-validating short-run signal, at least apparently affirming this view held by the super wealthy that inflation will increase economic uncertainty.

The economic problems of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is now shrinking at a 6% annual pace, and that number is probably going to get worse before it gets better. The chances of the island’s economy actually growing at any point in the foreseeable future seem remote: indeed, the country has essentially been in one long and nasty continuous recession since 2006.

Puerto Rico has $70 billion in debt outstanding, all of it needing to be repaid with interest — and the simple fact is that there’s no way it’s going to be able to do that, if its economy continues to shrink and its most talented nationals continue to decamp for the mainland, where their prospects are much brighter. Labor mobility from Puerto Rico to the rest of the US, and particularly to Florida, has never been higher, while most of the migration in the other direction comes in the form of retirees, who are not exactly going to kick-start the economy. In fact, in terms of the labor force participation rate, they’re just going to make matters worse, on an island where only 1.2 million of the 3.4 million inhabitants are employed.

Ryan McCarthy adds more.

Very good sentences about Bulgaria, the EU, and the DDR

For years people complained about the absence of labour mobility in the EU. Now we have it, the flaw in the institutional infrastructure is obvious.

Young people are moving from the weak economies on the periphery to the comparatively stronger ones in the core, or out of an ever older EU altogether. This has the simple consequence that the deficit issues in the core are reduced, while those on the periphery only get worse as health and pension systems become ever less affordable.

That is from the excellent Edward Hugh, here is more. Among other points, Hugh stresses just how much the “East German answer” involved extreme levels of labor mobility. There is also an illuminating analysis of the problems facing Bulgaria:

According to the 2011 census, Bulgaria has lost no less than 582,000 people over the last ten years. In a country of 7.3 million inhabitants this is a big deal. Further, it has lost a total of 1.5 million of its population since 1985, a record in depopulation not just for the EU, but also by global standards. The country, which had a population of almost nine million in 1985, now has almost the same number of inhabitants as in 1945 after World war II. And, of course, the decline continues.

Peter A. Diamond

Here is Diamond's home page, here is Diamond on Wikipedia. Diamond has been at MIT since 1970 and he is considered one of the bulwarks there, having produced many excellent students, including Bernanke and Andrei Shleifer. Here is the bit of most current interest:

On April 29, 2010, Diamond was announced by Barack Obama as one of three nominees to fill the three vacancies then present on the Federal Reserve Board, along with Janet Yellen and Sarah Bloom Raskin.[5] On August 5 the Senate returned Diamond's nomination to the White House, effectively rejecting his nomination. Ben Bernanke, the current Chairman of the Fed, was once a student of Diamond.

Some of Diamond's early work was in capital theory, as he outlined the conditions under which, in dynamic growth models, the level of capital could be inefficient. Read this paper, from 1965, which is still his most frequently cited work. It helped produce a standard framework for thinking about national debt and economic growth.

Diamond has contributed plenty to the theory of optimal taxation, in particular when linear commodity taxes are optimal and how to use the tax system for redistribution. See this paper with James Mirrlees (also a Nobel Laureate) and also this one. One implication is that taxing inputs often leads to more distortion than taxing outputs and you can think of this as one possible motivation for a consumption tax.

Here is Diamond's 1982 paper on macro and search theory, which I think of as his most influential. The abstract is classic Diamond:

Equilibrium is analyzed by a simple barter model with identical risk-neutral agents where trade is coordinated by a stochastic matching process. It is shown that there are multiple rational expectations equilibria, with all non-corner solution equilibria inefficient. This implies that an economy with this type of trade friction does not have a unique rate of natural unemployment.

The relationship to the current day U.S. is striking. One point he stresses is that subsidization of production can make sense and also that there can be real costs of converging to the lowest possible rate of unemployment too quickly. This remains an important "framework" paper for analyzing the interaction of search and aggregate demand. His other 1982 search paper implies that labor mobility will be less than is socially optimal. This paper on search theory shows that unemployment compensation can lead to better job matches, by limiting crowding externalities in the job market.

He and Olivier Blanchard wrote a classic piece on the Beveridge Curve, which is about the relationship between job vacacies and the unemployment rate. Some commentators cite the Beveridge Curve as evidence for structural unemployment, although this is controversial.

Diamond has written a great deal on social security, often at the applied level. Here is his paper criticizing social security privatization in Chile for its high costs. Here is his survey on social security reform proposals. Here is his paper on macro and social security reform. Here is a very good European talk he gave on pension issues. Diamond wrote a book with Peter Orszag on social security and he has been a major influence on Democratic Party thinking on this issue; the book looks closely at progressive price indexing rather than wage indexing of benefits. Here is a CBO summary and analysis of the plan. Much of Diamond's more formal social security analysis stresses risk-sharing issues and in general he often points out that social security proposals, including Bush's privatization idea, are not well-grounded in rigorous analysis.

Here Diamond tells us not to expect 7 percent stock returns for the ongoing future.

Diamond has many interests, here is his survey on contingent valuation and whether some number is better to use than no number at all. He and Stiglitz wrote a famous paper on risk and risk aversion.

Personally, my favorite Diamond paper is this short gem on the evaluation of infiinite utlity streams; it will make your head spin, as it asks whether we have coherent means of thinking about prospects with infinite utility and in general how intertemporal utility streams should be ordered. See also his related paper on stationary utility, co-authored with T.J. Koopmans.

Here is his short introduction on behavioral economics.

I think of Diamond as the classic MIT economist, especially of the earlier, pre-Acemoglu generation. Lots of theoretical rigor, though sometimes his theory pieces don't have a simple or simply analytic punchline. There is greater concern with risk, and stability conditions, and dynamic and border conditions, than you would see in a Chicago theory paper. There is a strong emphasis on the ability of government to implement welfare-improving schemes of the sort found in social democracies. The approach is quite technocratic — solve and advise. Public choice and political economy considerations take a back seat. High IQ. Of the MIT economists, he has done the most to pursue the Samuelson tradition of having a universal method and very broad interests. His papers remain central to public finance, welfare economic, intertemporal choice, search theory, macroeconomics, and other areas. His policy impact on social security has been significant.

Addendum: Levitt comments on Diamond.

Speak English, lower taxes

Megan McArdle writes:

It is hard for high levels of taxation to survive a right of exit;

Europe has mostly been protected (so far) by its many languages, which

make it harder to move. But as the EU increases labor mobility, expect

to hear more about harmful tax competition.

The story is about skilled Danes leaving the country so as to avoid higher taxes. The last time I was in Denmark I was struck how many service workers could not speak Danish (will a Spaniard or Hungarian really learn that language?) and in the workplace communicated in English. Greater policy competition is one of the most important results of so many Europeans speaking good English. High taxes and differential incomes, in turn, increase the incentive for people to learn good English, thereby creating a self-reinforcing dynamic. I’ve long thought that Europe will become more like the United States than vice versa, most of all through mobility and diversity, but I don’t think that is a very popular view.

Why the NYC congestion pricing plan is bad

I am seeing some critical comments on my latest column, mostly from people who are not reading it through, or in some cases they are making basic mistakes in economics. Let me start with part of my conclusion:

I suspect that I could endorse a properly targeted version of congestion pricing for Manhattan, for instance, one that encouraged mass transit without discouraging density.

Many people are responding by making a version of that point and thinking it contradicts me. Here are a few basic facts about the current proposal:

1. The off-peak price is too high at $17, relative to $23 for peak.

2. There is an odd and unjustified discrete notch at 60th St, which will cause further distortions of its own.

3. There is no difference for cars passing through and cars with passengers spending money or doing something productive in lower Manhattan.

This is not the traffic congestion charge you should be looking to implement.

A second line of responses (Erik B. and Alex) suggests that the congestion charge will not lower the flow of humans into Manhattan. I am sorry, but demand curves slope downward! The resulting auto commute does become more predictable and regular, but that holds only because there are fewer trips and to some extent because trips are time-shifted. (Note that the small gap between the $17 and $23 prices suggests a small benefit from time shifting.) Fewer outsiders will benefit from Manhattan, and those outsiders will skew richer and older. The methods for improving the quality of the trip really do lower the number of trip-makers, probably both peak and off-peak. It is not going to mean higher or even constant throughput for vehicles or humans. (If you think it does, does that imply a big subsidy to car trips would get us to a carless city? There are some non-linear scenarios where a congestion charge boosts throughput, such as when otherwise no cars move at all in extreme gridlock. In reality, it seems cars are moving at about 12 mph in Manhattan.)

The actual possible gain — oddly not cited by the critics — is that a congestion charge might get a given visitor more effective time spent learning from Manhattan. Though do note an offsetting effect — the higher the traffic problem, the more you will make each trip to Manhattan a grand and elaborate one, and it is your externality-less domestic time in Long Island that will suffer all the more. So per person learning externalities from effective time spent in Manhattan could go either way, noting the number of visitors still goes down.

You might think such a congestion charge improves welfare (a sounder point than suggesting it will not have a standard price effect), but the whole point is that Manhattan density involves massive positive externalities, including for visitors and note that visitors also finance the externality-rich activities of the natives:

In some urban settings, the clustering of human talent is of utmost importance. Manhattan is the densest urban area in the US, and it succeeds in large part because it is so crowded. You want to be there because other people want to be there. Even though I don’t live there, I nonetheless benefit from Manhattan, both when I visit and when I consume the television shows, movies, music, and art works that come, either directly or indirectly, out of this urban environment. Manhattan also supports America’s financial center, many tech start-ups, and much more.

I don’t want Manhattan to be less crowded, even though it probably would make many Manhattanites happier and less stressed. I want Manhattan to be efficient for me and others, not just for the residents. If there is any part of America where ideas rubbing together lead to great things, it is Manhattan (and the Bay Area). Arguably, Manhattan should be more crowded, at least if we consider everyone’s interest. That militates against congestion tolls, even though such charges are usually a good idea.

The actually useful solution is to make mass transit, most of all the subway, a reliable and predictable method of getting around. Right now it is not. (I doubt if lowering the already low subway prices gets you much.)

If you look at visits into Manhattan, whether by car or not, they already face lots of implicit taxes. Those include poor roads, mediocre subway performance, high variance public infrastructure including on issues such as trash, pollution issues, some degree of crime, awful connecting infrastructure (NJ Transit anyone?) and much more. And yet Manhattan is one of the world’s very top TFP factories and we are already taxing entry in so many different ways.

It does not make good economic sense to impose higher yet entry fees into that TFP factory. Given that multiple externalities are present, the correct mix is to lower many different costs of entry and mobility (including within Manhattan), while shifting the relative use benefits toward mass transit and the subway. Density really does have positive externalities here, and we all know how much idea makers and distributors are undercompensated.

There are a few more threads of responses on Twitter. One is to note the noise and pollution costs of vehicles. That is relevant, but fairly soon we will have lots more electric vehicles, which should be encouraged. The tolls will become a revenue source that lasts forever and they will not be taken away, but the noise and pollution costs of the vehicles soon will be much lower.

Another thread is to argue that most of the people who drive will switch to mass transit if there is a congestion cost. Some will, but we are asked to believe that a) current traffic congestion is so awful, b) people put up with it anyway, and c) they nonetheless can be easily nudged into taking mass transit. That is an uncomfortable blend of views that fails to understand the initial motivations behind the car trips. There are plenty of people with young kids, or elderly relatives, or multiple packages, or multiple stops, or unreliable mass transportation for getting back home at the end of the evening. Many of those people cannot feasibly switch to mass transit and that is precisely why they put up with the bad traffic. Say you finish your Manhattan doings at 10:45 p.m., and have to get back to your New Jersey home in a timely and safe manner. The PATH train will work for some, but a lot of these people really do need cars to consummate the trip.

(It is a theoretically defensible argument to claim that this congestion tax is the only way of financing mass transit improvements. That may or may not be true, but if it is one should still “regret” the plan, which is not the attitude people are taking. And are there guarantees this will lead to a refurbishment of the subway? It has proven remarkably difficult to improve the system, and that is with rising NYC budgets. Another argument that might work is if non-car visitors so hate seeing cars in Manhattan that the net human inflow, due to auto trips, goes down rather than up. Do note however that the car trips are still helping to finance retail and cultural infrastructure that attracts the non-car visitors, so don’t just take complaints about cars at face value. Furthermore this car hatred factor also should become less serious as we transition to electric vehicles.)

On net, do you think our most important cities should be more or less dense? If you support YIMBYism, which surely does make traffic worse, have you not already answered that question? So either become a NIMBY or — better yet — be a little more consistent applying your intuitions about the net positive externality from Manhattan density. A simple way to put the point is that an export tax on your TFP factory is unlikely to be the best way to reduce congestion.

Saturday assorted links

2. Chat with historical figures, 20,000 of them. When will they do economists? And using GPT for therapy, how do you think it did? People preferred the GPT, until they found out they were speaking with a machine.

3. What some top chess players won in prize money.

4. Claims about quantum computing.

5. Rasheed Griffith on where to eat in Panama.

6. “The use of a longitudinal database of Famine immigrants who initially settled in New York and Brooklyn indicates that the Famine Irish had far more occupational mobility than previously recognized. Only 25 percent of men ended their working careers in low-wage, unskilled labor; 44 percent ended up in white-collar occupations of one kind or another—primarily running saloons, groceries, and other small businesses.” Link here.

From the comments, on single payer

Moving From Opportunity: The High Cost of Restrictions on Land Use

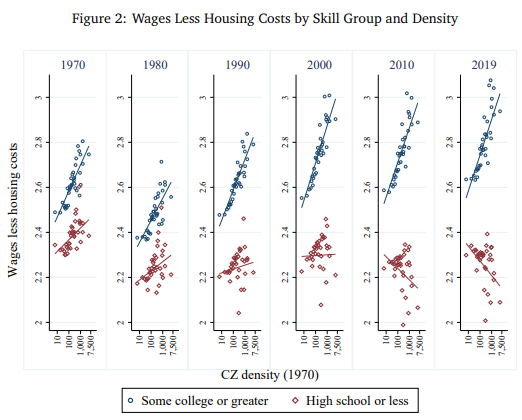

As I wrote earlier, it used to be that poor people moved to rich places. A janitor in New York, for example, used to earn more than a janitor in Alabama even after adjusting for housing costs. As a result, janitors moved from Alabama to New York, in the process raising their standard of living and reducing income inequality. Today, however, after taking into account housing costs, janitors in New York earn less than janitors in Alabama. As a result, poor people no longer move to rich places. Indeed, there is now a slight trend for poor people to move to poor places because even though wages are lower in poor places, housing prices are lower yet.

Ideally, we want labor and other resources to move from low productivity places to high productivity places–this dynamic reallocation of resources is one of the causes of rising productivity. But for low-skill workers the opposite is happening – housing prices are driving them from high productivity places to low productivity places. Furthermore, when low-skill workers end up in low-productivity places, wages are lower so there are fewer reasons to be employed and there aren’t high-wage jobs in the area so the incentives to increase human capital are dulled. The process of poverty becomes self-reinforcing.

Why has housing become so expensive in high-productivity places? It is true that there are geographic constraints (Manhattan isn’t getting any bigger) but zoning and other land use restrictions including historical and environmental “protection” are reducing the amount of land available for housing and how much building can be done on a given piece of land. As a result, in places with lots of restrictions on land use, increased demand for housing shows up mostly in house prices rather than in house quantities.

Moreover, as I also argued earlier, even though the net wage is still positive for college-educated workers a signficant share of the returns to education are actually going to land owners! Enrico Moretti (2013) estimates that 25% of the increase in the college wage premium between 1980 and 2000 was absorbed by higher housing costs. Moreover, since the big increases in housing costs have come after 2000, it’s very likely that an even larger share of the college wage premium today is being eaten by housing. High housing costs don’t simply redistribute wealth from workers to landowners. High housing costs reduce the return to education, reducing the incentive to invest in education. Thus higher housing costs have reduced human capital and the number of skilled workers with potentially significant effects on growth.

The Parent Trap–Review of Hilger

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Hilger argues that the problems of poverty, pathology and inequality that bedevil the United States are not primarily due to poor schools, discrimination, or low incomes per se. The primary cause is parents: parents who are unable to teach their children the skills that are necessary to succeed in the modern world. Since parents can’t teach the necessary skills, Hilger calls for the state to take their place with a dramatic expansion of not just child care but collective parenting.

Let’s unpack some details. Begin with schooling. It’s very common to bemoan the state of schools in the “inner city” or to complain about “local financing” which supposedly guarantees that poor counties will have underfunded schools. All of this, however, is decades out-of-date.

A hundred years ago there really were massive public-school resource gaps by class and race. These days, however, state and federal spending play a larger role than local property tax revenue and distribute educational resources more progressively….In fact, when we include federal aid, 42 states spent more on poor school districts than on rich school districts in 2012. The same pattern holds between schools within districts

….The highest spending districts are large urban centers such as New York City, Boston and Baltimore. These cities spend large sums to educate rich and poor children alike. p. 10-11

Hilger is correct. No matter what you saw on The Wire, Baltimore spends more than sixteen thousand dollars per student, among the highest in the nation in large school districts and above average for the nation as a whole. Public schools are quite egalitarian in funding with any bias running towards more funding for poorer districts.

Schools, Hilger writes are “actually the smallest and most equalizing part of a much larger skill-building system.” The real problem, says Hilger, are parents.

But what about discrimination? When it comes to wage discrimination, Hilger is brutally honest:

If we compare individuals with similar cognitive test scores, Black college graduates earn higher wages than white college graduates. Studies that don’t control for test score differences but examine earnings gaps within specific professions—lawyers, physicians, nurses, engineers, scientists—tend to find Black workers earn zero to 10 percent less than white workers. These gaps could reflect discrimination, unmeasured skill differences, or other factors such as geography. In any case, such gaps are small compared to the 50 percent overall Black-white earnings gap and reinforce the idea that closing skills gaps would go a long way toward closing income gaps.

Hilger argues that racism does play an important role in explaining Black-white wage differentials but it’s the historical racism that made black parents less skilled and less able to pass on skills to their children. In the twentieth century, Asians, Hilger argues, were discriminated against in the United States at least much as Black Americans. But the Asians that came to the United States had high skills while the legacy of slavery meant that Black Americans began with low skills. Asians, therefore, were better able to overcome discrimination. The success of Nigerians and Jamaican immigrants in the United States also speaks to this point. (Long time readers may recall that in 2016 I dubbed Hilger’s paper on Asian Americans and Black Americans the Politically Incorrect Paper of the Year .)

Parental investment is surely important but Hilger overstates his case. He writes as if poorer parents have neither the abilities nor the time to teach their children while richer, better educated parents simply invest lots of hours and money imbuing their children with skills:

…the enormous variation in parents’ own academic skills has big implications for kids because we also demand that parents try to be tutors. During normal times, parents in America spend an average of six hours per week helping—or trying to help—their kids with school work. Six hours per week is more than K12 math and English teachers get with children…good tutoring by parents for six hours a week, every week, year after year of childhood could raise children’s future earnings by as much as $300,000.

The data on the effectiveness of SAT test-prep suggests that these efforts are not nearly so effective as Hilger argues. The parental investment story also doesn’t fit my experience. I didn’t spend six hours a week helping my kids with their homework. I doubt most parents do. I simply assumed my kids would do their work. I do recall that we signed my kids up for tutoring at Kumon, the Japanese math education center. My kids would complain bitterly when we took them for drill on the weekend. It was mostly filling out rote forms and my kids would hide or bury their drill sheets so we were always behind. Driving my kids to the Kumon center, monitoring them. and forcing them to do the work when they rebelled like longshoreman on work-to-rule was time consuming and it was ruining our weekends. I felt guilty, but after a while, my wife and I gave up. Today one of my sons is a civil engineer and the other is a math and economics major at UVA.

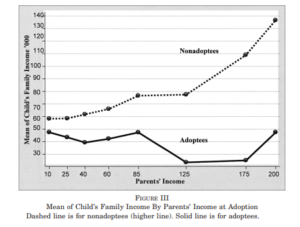

Hilger has an answer to this line of objection, or at least he says he does, but to my mind it’s a very odd answer. He argues, relying heavily on Sacerdote, that adoption studies show that more skilled parents result in more skilled kids. I find that answer odd because my reading of Sacerdote is that the effect of parents are small after you control for genetics—this is, as Hilger acknowledges, the conventional wisdom among psychologists. (See Caplan for an excellent review of the literature). It is true that Sacerdote plays up the effect of parents, but it looks small to me. Here is the effect of the adopted mother’s maternal education on the child’s education.

As you can see there is an effect but it is almost all from the mother going from having less than a high school education to graduating high school (11 to 12 years). In contrast, the mother can move from graduating high school to having a PhD and there is very little change in the education level of an adoptee. Note, however, that the effect on non-adoptees, i.e. biological children, is much larger throughout the entire range which suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

I am not surprised that there is some effect of parental education on child’s education because going to college is in part a cultural issue. Parents can influence cultural aspects of their children’s identity such as whether a child grows up up nominally Catholic, Mormon, or Hindu but they have relatively little effect on child religiosity, let alone personality or IQ. I think that a large fraction of the college wage premium is signaling (50% is a moderate estimate, Caplan thinks 90% is closer to the truth), so I am also not overly excited about college attendance as a marker of success.

The effect of parental income on the income of child adoptees is even more dramatic than on education—which is to say negligible. The income of the adopted parents has zero effect (!) on child’s income even as parent’s income varies by a factor of 20! The only correlation is with non-adoptee income—which again suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

At this point in the book, it was almost inevitable that we were going to get yet another paean to the Perry Preschool Project and indeed Hilger waxes enthusiastically about Perry. Seriously? The Perry Preschool project started in the 1960s and had just 123 participants (58 in treatment and 65 in control!). There are more papers about the Perry Preschool project than there were participants. I am jaded.

Aside from the small sample size, the project had imperfect randomization and missing data and most importantly limited external validity. The Perry Preschool project treated a small group of disadvantaged African American children with low-IQs (IQs of 70-85 were part of the selection criteria). The treatment is usually described as “active learning pre-school” but it was more intrusive than that. Every week counselors would go to the homes of the kids to teach the parents (mostly mothers) how to raise their children. The training was important to the program. Indeed, Hilger notes, without sense of irony, that “facilitating greater skill growth in low-income children was so complicated that it required home visitors with advanced postsecondary degrees.” (p. 89). And what were the results?

The results were good! (Heckman et al. 2010, Belfield et al. 2006). But in the popular literature the impression one gets is that the program took a bunch of disadvantaged kids and helped them read and write, making them more middle-class and successful. Some of that happened but the big gains actually happened because the participants, especially the boys, were so socially dangerous and destructive that even a bit of normalization made life substantially better for everyone else. In particular 82% of the treated group of 33 males had been arrested by age 40, including for one murder, 4 rapes, 8 robberies, 11 assaults and 14 burglaries. The control group were worse. In the control group of 39 males there were 2 murders. Indeed the reduction of one murder in the treatment group accounts for a significant benefit of the entire Perry PreSchool project.

Hilger, to his credit, is reasonably clear that what is really needed is an intensive program for disadvantaged African Americans, especially males. In a stunning sentence he writes:

The more we rely on families rather than professionals to build skills in children, the tighter we link people’s current prospects to the prospects of their ancestors. p. 134

But he soon forgets or papers over the context of the Perry Preschool project and like everyone else in the literature uses this to support a national program for which there is no external validity. It’s hard to believe, given the lack of external validity, but Heckman et al. (2010) only exagerate mildly when they write:

The economic case for expanding preschool education for disadvantaged children is largely based on evidence from the HighScope Perry Preschool Program…

Hilger’s case for the difficulty of parenting is well taken—the FAFSA was a nightmare that taxed two PhDs in my family. But the bottom line is that most parents do just fine. Moreover, it’s shocking that in recounting the difficulties of parenting Hilger says hardly one word about an obvious factor which makes parenting more than twice as hard. Namely, single parenting. I was a single parent. Once for a whole week. Don’t do it. Get married, stay married. Perhaps Hilger didn’t want to appear to be too conservative.

Instead of recommending marriage and small targeted programs and more experiments, Hilger goes full Plato.

What would it look like if we [asked]…less not more of parents? It would look like professional experts managing more than the meagre 10 percent of children’s time currently managed by our public K12 system—much more. p. 184

And why should we do this? Because we are all part slaves and part slave-owners on a giant collective farm:

As fellow citizens who benefit from tax revenue, we all—even those of us without children—collectively own about 30 percent of any additional income other people’s children wind up earning. p. 197

Ugh. We own ourselves, not one another. Society isn’t about maximizing the collective it’s about free individuals coming together to produce rules so that we can enjoy the benefits of collective action while still living in a diverse society that respects individual rights, beliefs, and ways of living.

I told you I hated parts of The Parent Trap but Hilger has written an interesting and challenging book and he is mostly right that neither schooling nor labor market discrimination play a major role in the black-white wage gap. Hilger is probably also right that we spend too much on the elderly relative to the young. The idea of greater state involvement in the raising of children is on the table today in a way it hasn’t been for some time. See also Dana Susskind’s recent book Parent Nation. Changes on the margin may be warranted. Nevertheless, I stand with Aristotle and not Plato in thinking that raising children is better done by parents than by the state.

Progresa after 20 Years

Remember the Mexican cash transfer program, sometimes used to support education? Some new results are in, and the program is looking pretty good:

In 1997, the Mexican government designed the conditional cash transfer program Progresa, which became the

worldwide model of a new approach to social programs, simultaneously targeting human capital accumulation

and poverty reduction. A large literature has documented the short and medium-term impacts of the Mexican

program and its successors in other countries. Using Progresa’s experimental evaluation design originally rolled out in 1997-2000, and a tracking survey conducted 20 years later, this paper studies the differential long-termimpacts of exposure to Progresa. We focus on two cohorts of children: i) those that during the period of differential exposure were in-utero or in the first years of life, and ii) those who during the period of differential exposure were transitioning from primary to secondary school. Results for the early childhood cohort, 18–20-year-old at endline, shows that differential exposure to Progresa during the early years led to positive impacts on educational attainment and labor income expectations. This constitutes unique long-term evidence on the returns of an at-scale intervention on investments in human capital during the first 1000 days of life. Results for the school cohort – in their early 30s at endline – show that the short-term impacts of differential exposure to Progresa on schooling were sustained in the long-run and manifested themselves in larger labor incomes, more geographical mobility including through international migration, and later family formation.

Here is the full paper by M. Caridad Araujo and Karen Macours from Poverty Action Lab.

Emergent Ventures India, new winners, third Indian cohort

Angad Daryani / Praan

Angad Daryani is 22-year-old social entrepreneur and inventor from Mumbai, and his goal is to find solutions for clean air at a low cost, accessible to all. He received his EV grant to build ultra-low cost, filter-less outdoor air purification systems for deployment in open areas through his startup Praan. Angad’s work was recently covered by the BBC here.

Swasthik Padma

Swasthik Padma is a 19-year-old inventor and researcher. He received his EV grant to develop PLASCRETE, a high-strength composite material made from non-recyclable plastic (post-consumer plastic waste which consists of Multilayer, Film Grade Plastics and Sand) in a device called PLASCREATOR, also developed by Swasthik. The final product serves as a stronger, cost-effective, non-corrosive, and sustainable alternative to concrete and wood as a building material. He is also working on agritech solutions, desalination devices, and low cost solutions to combat climate change.

Ajay Shah

Ajay Shah is an economist, the founder of the LEAP blog, and the coauthor (with Vijay Kelkar) of In Service of the Republic: The Art and Science of Economic Policy, an excellent book, covered by Alex here. He received his EV grant for creating a community of scholars and policymakers to work on vaccine production, distribution, and pricing, and the role of the government and private sector given India’s state capacity.

Meghraj Suthar

Meghraj Suthar, is an entrepreneur, software engineer, and author from Jodhpur. He founded Localites, a global community (6,000 members from more than 130 countries) of travelers and those who like to show around their cities to travelers for free or on an hourly charge. He also writes inspirational fiction. He has published two books: The Dreamers and The Believers and is working on his next book. He received his EV grant to develop his new project Growcify– helping small & medium-sized businesses in smaller Indian cities to go online with their own end-to-end integrated e-commerce app at very affordable pricing.

Jamie Martin/ The Queen’s English

Jamie Martin and Sandeep Mallareddy founded The Queen’s English to develop a tool to help speak English. Indians who speak English earn 5x more than those who don’t. The Queen’s English provides 300 hours of totally scripted lesson plans on a simple Android app for high quality teaching by allowing anyone who can speak English to teach high quality spoken English lessons using just a mobile phone.

Rubén Poblete-Cazenave

Rubén Poblete-Cazenave is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Economics at Erasmus University Rotterdam. His work has focused on studying topics on political economy, development economics and economics of crime, with a particular interest in India. Rubén received his EV grant to study the dynamic effects of lockdowns on criminal activity and police performance in Bihar, and on violence against women in India.

Chandra Bhan Prasad

Chandra Bhan Prasad is an Indian scholar, political commentator, and author of the Bhopal Document, Dalit Phobia: Why Do They Hate Us?, What is Ambedkarism?, Dalit Diary, 1999-2003: Reflections on Apartheid in India, and co-author author (with D Shyam Babu and Devesh Kapur) of Defying the Odds: The Rise of Dalit Entrepreneurs. He is also the founder of the ByDalits.com e-commerce platform and the editor of Dalit Enterprise magazine. He received his EV grant to pursue his research on Dalit capitalism as a movement for self-respect.

Praveen Tiwari

Praveen Tiwari is a rural education entrepreneur in India. At 17, he started Power of Youth to increase education and awareness among rural students in his district. To cope with the Covid lockdown he started the Study Garh with a YouTube channel to provide better quality educational content to rural students in their regional language (Hindi).

Preetham R and Vinayak Vineeth

Preetham R. and Vinayak Vineeth are 17-year-old high-schoolers from Bangalore. Preetham is interested in computing, futurism and space; and Vinayak is thinking about projects ranging from automation to web development. They received their EV grant for a semantic text analysis system based on graph similarity scores. The system (currently called the Knowledge Engine) will be used for perfectly private contextual advertising and will soon be expanded for other uses like better search engines, research tools and improved video streaming experiences. They hope to launch it commercially by the end of 2022.

Shriya Shankar:

Shriya Shankar is a 20-year-old social entrepreneur and computer science engineer from Bangalore and the founder of Project Sitara Foundation, which provides accessible STEM education to children from underserved communities. She received her EV grant to develop an accessible ed-tech series focused on contextualizing mathematics in Kannada to make learning more relatable and inclusive for children.

Baishali Bomjan and Bhuvana Anand

Baishali and Bhuvana are the co-founders of Trayas Foundation, an independent research and policy advisory organization that champions constitutional, social, and market liberalism in India through data-informed public discourse. Their particular focus is on dismantling regulatory bottlenecks to individual opportunity, dignity and freedom. The EV grant will support Trayas’s work for reforms in state labor regulations that ease doing business and further prosperity, and help end legal restrictions placed on women’s employment under India’s labor protection framework to engender economic agency for millions of Indians.

Akash Bhatia and Puru Botla / Infinite Analytics

Infinite Analytics received their first grant for developing the Sherlock platform to help Indian state governments with mobility analysis to combat Covid spread. Their second EV grant is to scale their platform and analyze patterns to understand the spread of the Delta variant in the 2021 Covid wave in India. They will analyze religious congregations, election rallies, crematoria footfalls and regular daily/weekly bazaars, and create capabilities to understand the spread of the virus in every city/town in India.

PS Vishnuprasad

Vishnuprasad is a 21-year-old BS-MS student at IISER Tirupati. He is interested in the intersection of political polarization and network science and focused on the emergence and spread of disinformation and fake news. He is working on the spread of disinformation and propaganda in spaces Indians use to access information on the internet. He received his EV grant to build a tool that tracks cross-platform spread of disinformation and propaganda on social media. He is also interested in the science of cooking and is a stand-up comedian and writer.

Prem Panicker:

Prem Panicker is a journalist, cricket writer, and founding editor of peepli.org, a site dedicated to multimedia long form journalism focused on the environment, man/animal conflict, and development. He received an EV grant to explore India’s 7,400 km coastline, with an emphasis on coastal erosion, environmental degradation, and the consequent loss of lives and livelihoods.

Vaidehi Tandel

Vaidehi Tandel is an urban economist and Lecturer at the Henley Business School in University of Reading. She is interested in understanding the challenges and potential of India’s urban transformation and her EV grant will support her ongoing research on the political economy of urbanization in India. She was part of the team led by Malani that won the EV Covid India prize.

Abhinav Singh

Abhinav recently completed his Masters in the Behavioral and Computational Economics program at Chapman University’s Economic Science Institute. His goal is to make political economy ideas accessible to young Indians, and support those interested in advancing critical thinking over policy questions. He received his EV grant to start Polekon, a platform that will host educational content and organize seminars on key political economy issues and build a community of young thinkers interested in political economy in India.

Bevin A./Contact

CONTACT was founded by two engineers Ann Joys and Bevin A. as a low-cost, voluntary, contact tracing solution. They used RFID tags and readers for consenting individuals to log their locations at various points like shops, hotels, educational institutions, etc. These data are anonymized and analyzed to track mobility and develop better Covid policies, while maintaining user anonymity.

Onkar Singh Batra

Onkar Singh is a 16-year-old developer/researcher and high school student in Jammu. He received his first EV grant for his Covid Care Jammu project. His goal is to develop India’s First Open-Source Satellite, and he is founder of Paradox Sonic Space Research Agency, a non-profit aerospace research organization developing inexpensive and open-source technologies. Onkar received his second EV grant to develop a high efficiency, low cost, nano satellite. Along with EV his project is also supported by an Amateur Radio Digital Communications (ARDC) grant. Onkar has a working engineering model and is developing the final flight model for launch in 2022.

StorySurf

Storysurf, founded by Omkar Sane and Chirag Anand, is based on the idea that stories are the simplest form of wisdom and that developing an ocean of stories is the antidote to social media polarization. They are developing both a network of writers, and a range of stories between 6-300 words in a user-friendly app to encourage people to read narratives. Through their stories, they hope to help more readers consume information and ideas through stories.

Naman Pushp/ Airbound

Airbound is cofounded by its CEO Naman Pushp, a 16 year old high-schooler from Mumbai passionate about engineering and robotics, and COO Faraaz Baig, a 20 year old self-taught programmer and robotics engineers from Bangalore. Airbound aims to make delivery accessible by developing a VTOL drone design that can use small businesses as takeoff/landing locations. They have also created the first blended wing body tail sitter (along with a whole host of other optimizations) to make this kind of drone delivery possible, safe and accessible.

Anup Malani / CMIE / Prabhat Jha

An joint grant to (1) Anup Malani, Professor at the University of Chicago, (2) The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), and (3) Prabhat Jha, Professor at University of Toronto and the Centre for Global Health Research, to determine the extent to which reported excess deaths in India are due to Covid. Recent studies show that that the pandemic in India may be associated with between 3 million to 4.9 million excess deaths, roughly 8-12 times officially reported number of COVID deaths. To determine how many of these deaths are statistically attributable to Covid, they will conduct verbal autopsies on roughly 20,000 deaths, with the results to be made publicly available.

And finally:

Aditya Dar/The Violence Archive

A joint grant to Aaditya Dar, an economist at Indian School of Business, Kiran Garimella, a computer scientist at Rutgers University and Vasundhara Sirnate, a political scientist and journalist for creating the India Violence Archive. They will use machine learning and natural language processing to develop an open-source historical record of collective public violence in India over 100 years. The goal is to create accessible and high-quality public data so civil society can pursue justice and governments can make better policy.

Those unfamiliar with Emergent Ventures can learn more here and here. EV India announcement here. More about the winners of EV India second cohort here. To apply for EV India, use the EV application click the “Apply Now” button and select India from the “My Project Will Affect” drop-down menu.

Note that EV India is led and run by Shruti Rajagopalan, I thank her for all of her excellent work on this!

Here is Shruti on Twitter, and here is her excellent Ideas of India podcast. Shruti is herself an earlier Emergent Ventures winner, and while she is very highly rated remains grossly underrated.

That is from “Sure.”

TC again: There is a natural tendency on the internet to think that all universal coverage systems are single payer, but they are not. There is also a natural tendency to contrast single payer systems with freer market alternatives, but that is also an option not a necessity. You also can contrast single payer systems with mixed systems where both the government and the private sector have a major role, such as in Switzerland.

I’ll say it again: single payer systems just don’t have the resources or the capitalization to do well in the future, or for that matter the present. Populations are aging, Covid-related costs (including burdens on labor supply) have been a problem, income inequality pulls away medical personnel from government jobs, and health care costs have been rising around the world. Citizens will tolerate only so much taxation, plus mobility issues may bite. So the single payer systems just don’t have enough money to get the job done. That stance is conceptually distinct from thinking health care should be put on a much bigger market footing. But at the very least it will require a larger private sector role for the financing.