Results for “pandemic model” 107 found

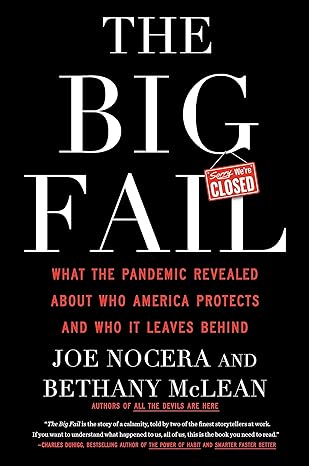

The Big Fail

The Big Fail, Joe Nocera and Bethany McLean’s new book about the pandemic, is an angry book. Rightly so. It decries the way the bien pensant, the self-righteously conventional,  were able to sideline, suppress and belittle other voices as unscientific, fraudulent purveyors of misinformation. The Big Fail gives the other voices their hearing— Martin Kulldorff, Sunetra Gupta, Jay Bhattacharya and Emily Oster are recast not as villains but as heroes; as is Ron DeSantis who is given credit for bucking the conventional during the pandemic (Nocera and McLean wonder what happened to the data-driven DeSantis, as do I.)

were able to sideline, suppress and belittle other voices as unscientific, fraudulent purveyors of misinformation. The Big Fail gives the other voices their hearing— Martin Kulldorff, Sunetra Gupta, Jay Bhattacharya and Emily Oster are recast not as villains but as heroes; as is Ron DeSantis who is given credit for bucking the conventional during the pandemic (Nocera and McLean wonder what happened to the data-driven DeSantis, as do I.)

Amazingly, even as highly-qualified epidemiologists and economists were labelled “anti-science” for not following the party line, the biggest policy of them all, lockdowns, had little to no scientific backing:

…[lockdowns] became the default strategy for most of the rest of the world. Even though they had never been used before to fight a pandemic, even though their effectiveness had never been studied, and even though they were criticized as authoritarian overreach—despite all that, the entire world, with a few notable exceptions, was soon locking down its citizens with varying degrees of severity.

In the United States, lockdowns became equated with “following the science.” It was anything but. Yes, there were computer models suggesting lockdowns would be effective, but there were never any actual scientific studies supporting the strategy. It was a giant experiment, one that would bring devastating social and economic consequences.

The narrative lined up “scientific experts” against “deniers, fauxers, and herders” with the scientific experts united on the pro-lockdown side (the following has no indent but draws from an earlier post). But let’s consider. In Europe one country above all others followed the “ideal” of an expert-led pandemic response. A country where the public health authority was free from interference from politicians. A country where the public had tremendous trust in the state. A country where the public were committed to collective solidarity and public welfare. That country, of course, was Sweden. Yet in Sweden the highly regarded Public Health Agency, led by state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, an expert in infectious diseases, opposed lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the general use of masks.

It’s important to understand that Tegnell wasn’t an outsider marching to his own drummer, anti-lockdown was probably the dominant expert opinion prior to COVID. In a 2006 review of pandemic policy, for example, four highly-regarded experts argued:

It is difficult to identify circumstances in the past half-century when large-scale quarantine has been effectively used in the control of any disease. The negative consequences of large-scale quarantine are so extreme (forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.

Travel restrictions, such as closing airports and screening travelers at borders, have historically been ineffective.

….a policy calling for communitywide cancellation of public events seems inadvisable.

The authors included Thomas V. Inglesby, the Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, one of the most highly respected centers for infectious diseases in the world, and D.A. Henderson, the legendary epidemiologist widely credited with eliminating smallpox from the planet.

Nocera and McLean also remind us of the insanity of the mask debate, especially in the later years of the pandemic.

But by the spring of 2022, the CDC had dropped its mask recommendations–except, incredibly, for children five and under, who again, were the least likely to be infected.

…Once again it was Brown University economist Emily Oster who pointed out how foolish this policy was…The headline was blunt: Masking Policy is Incredibly Irrational Right Now. In this article she noted that even as the CDC had dropped its indoor mask requirements for kids six and older, it continued to maintain the policy for younger children. “Some parents of young kids have been driven insane by this policy,” Oster wrote, “I sympathize–because the policy is completely insane…”

As usual, her critics jumped all over her. As usual, she was right.

Naturally, I don’t agree with everything in the Big Fail. Nocera and McLean, for example, are very negative on the role of private equity in hospitals and nursing homes. My view is that any theory of what is wrong with American health care is true because American health care is wrong in every possible way. Still, I don’t see private equity as a driving force. It’s easy to find examples where private equity owned nursing homes performed poorly but so did many other nursing homes. More systematic analyses find that PE owned nursing homes performed about the same, worse or better than other nursing homes. Personally, I’d bet on about the same overall. Covid in the Nursing Homes: The US Experience (open), my paper with Markus Bjoerkheim, shows that what mattered more than anything else was simply community spread (see also this paper for the ways in which I disagreed with the GBD approach). More generally, my paper with Robert Omberg, Is it possible to prepare for a pandemic? (open) finds that nations with universal health care, for example, didn’t have fewer excess deaths.

The bottom line is that vaccines worked and everything else was a sideshow. Had we approved the vaccines even 5 weeks earlier and delivered them to the nursing homes, we could have saved 14,000 lives and had we vaccinated nursing home residents just 10 weeks earlier, before the vaccine was approved, as Deborah Birx had proposed, we might have saved 40,000 lives. Nevertheless, Operation Warp Speed was the shining jewel of the pandemic. The lesson is that we should fund further vaccine R&D, create a library of prototype vaccines against potential pandemic threats, streamline our regulatory systems for rapid response, agree now on protocols for human challenge trials and keep warm rapid development systems so that we can produce vaccines not in 11 months but in 100 days.

The Big Fail does a great service in critiquing those who stifled debate and in demanding a full public accounting of what happened–an accounting that has yet to take place.

Addendum 1: I have reviewed most of the big books on the pandemic including the National Covid Commission’s Lessons from the COVID WAR, Scott Gottlieb’s Uncontrolled Spread, Michael Lewis’s The Premonition, Andy Slavitt’s Preventable and Abutaleb and Paletta’s Nightmare Scenario.

Addendum 2: I also liked Nocera and McLean’s All the Devils are Here on the financial crisis. Sad to say that the titles could be swapped without loss of validity.

The Great Depression is Over!

Throughout the 20th century, the Great Depression dominated macroeconomic discourse, engaging prominent economists such as Keynes, Hayek, Friedman, Lucas, and Prescott. Most  principles of macroeconomics textbooks spend considerable time analyzing the Great Depression as it was this event which galvanized thinking about aggregate demand, bank runs, fiscal policy and money policy. However, the Great Depression occurred nearly a century ago and in a vastly different world, rendering its analysis more relevant to economic history than contemporary macroeconomics. We think it’s time to revise.

principles of macroeconomics textbooks spend considerable time analyzing the Great Depression as it was this event which galvanized thinking about aggregate demand, bank runs, fiscal policy and money policy. However, the Great Depression occurred nearly a century ago and in a vastly different world, rendering its analysis more relevant to economic history than contemporary macroeconomics. We think it’s time to revise.

In the forthcoming edition of Modern Principles we excise the Great Depression and focus instead on the Great Financial Crisis and the Pandemic Recession as exemplifying the core of macroeconomics and policy. These events showcase a demand-driven recession followed by a supply-driven one, well illustrated by our dynamic AD-AS model. Focusing on these recessions also moves the lessons beyond the shifting of curves and towards important discussions of shadow banking, securitization, the microeconomics of externalities, and how monetary and fiscal policy must change when the goal – as during a pandemic — is not to get people back to work!

The lessons drawn from these significant and more recent recessions will inform policymakers as they deal with future recessions and will be the subject of analysis by economists for generations to come. A textbook for the 21st century must analyze the macroeconomics of the 21st century.

Plagues Upon the Earth

Kyle Harper’s Plagues Upon the Earth is a remarkable accomplishment that weaves together microbiology, history, and economics to understand the role of diseases in shaping human history. Harper, an established historian known for his first three books on Rome and late antiquity, has an impressive command of virology, bacteriology, and parasitology as well as history and economics. In “Plagues Upon the Earth.” he explains all of these clearly and with many arresting turns of phrase and insights:

Kyle Harper’s Plagues Upon the Earth is a remarkable accomplishment that weaves together microbiology, history, and economics to understand the role of diseases in shaping human history. Harper, an established historian known for his first three books on Rome and late antiquity, has an impressive command of virology, bacteriology, and parasitology as well as history and economics. In “Plagues Upon the Earth.” he explains all of these clearly and with many arresting turns of phrase and insights:

There are about seventy-three bacteria among major human pathogens–out of maybe a trillion bacterial species on earth. To imagine bacteria primarily as pathogens is about as fair as thinking of human beings as mostly serial killers.

Despite the tingling fear we still feel in the face of large animals, fire made predators a negligible factor in human population dynamics. The warmth, security and mystic peace you feel around the campfire has been instilled by almost two million years of evolutionary advantage given to us by the flames.

Mosquitos are vampires with wings….The blood heist itself is an amazing feat. Following contrails of carbon dioxide that lead to her mark, the female mosquito lands and starts probing. Once she reaches her target, she inserts her tube-like needle, as flexible as a plumber’s snake, into the skin. She pokes a dozen or more times until she hits her mark. The proboscis itself is moistened with compounds that anesthetize the victim’s skin and deter coagulation. For a tense minute or two, she pulls blood into her gut, taking on several times her own weight, as much as she can carry and still fly. She has stolen a valuable liquid full of energy and free metals. Engorged, she unsteadily makes her getaway, desperate for the nearest vertical plane to land and recuperate, as her body digests the meal and keeps only what is needful for her precious eggs.

What I like best about Plagues Upon the Earth is that Harper thinks like an economist. I mean this in two senses. First, his chapters on the Wealth and Health of Nations and Disease and Global Divergence are alone worth the price of admission. In these chapters, Harper brings disease to the fore to understand why some nations are rich and others poor but he is well aware of all the other explanations and weaves the story together with expertise.

The second sense in which Harper thinks like an economist is deeper and more important. He has a model of parasites and their interactions with human beings. That model, of course, is the evolutionary model. To a parasite, human beings are a desirable host:

Just as robbers steal from banks because that is where the money is, parasites exploit human bodies because there are high rewards for being able to do so…. for a parasite, there is now more incentive to exploit humans than ever…look at human energy consumption…in a developed society today, every individual consumer is the rough ecological equivalent to a herd of gazelles.

That parasites are driven by “incentives” would seem to be nearly self-evident but in the hands of a master simple models can lead to surprising hypothesis and conclusions. Harper is the Gary Becker of parasite modeling. Here’s a simple example: human beings have changed their environments tremendously in the past several hundred years but that change in human environment created new incentives and constraints on parasites. Thus, it’s not surprising that most human parasites are new parasites. Chimpanzee parasites today are about the same as those that exploited chimpanzees 100,000 years ago but human parasites are entirely different. Indeed, because the human-host environment has changed, our parasites are more novel, narrow, and nasty than parasites attacking other species.

It’s commonly suggested that one of the reasons we are encountering novel parasites is due to our disruptions of natural ecosystems, venturing into territories previously unexplored by humans, thereby releasing ancient parasites that have lain dormant for millennia. Like the alleged curse of Tutankhamun’s tomb we are unleashing ancient foes! Similarly, concerns are voiced that climate change, through its effect on permafrost melt, may liberate “zombie” parasites poised for retaliation. But ancient parasites are not fit for human hosts as they have not evolved within the context of the contemporary human environment. So, while I don’t trivialize the potential consequences of melting permafrost, I think we should fear much more relatively recent diseases such as measles, cholera, polio, Ebola, AIDS, Zika, and COVID-19. Not to mention whatever entirely new disease evolution is bound to throw in our path.

Indeed, one of the most interesting speculation’s in Plagues Upon the Earth is that “global divergences in health may have reached their maxima in the early twentieth century.” The reason is that urbanization and transportation turned the new diseases of the industrial era, like cholera, tuberculosis and the plague (the latter older diseases but ideally primed for the industrial era) into pandemics (also a relatively recent word) at a time when only a minority of the world had the tools to combat the new diseases.

Science, of course, is giving us greater understanding and control of nature but our very success increases the incentives of parasites to breach our defenses.

[Thus,] the narrative is not one of unbroken progress, but one of countervailing pressures between the negative health feedback of growth and humanity’s rapidly expanding but highly unequal capacities to control threats to our health.

The strange recession that is Czechia (from my email)

From the very perceptive Kamil Kovar, these are his words I will not double indent:

“Seeing your recent brief post on recession I was wondering whether you are thinking about writing a longer post on the topic of recessions in general? I find the recent macroeconomic developments very intriguing, as they challenge my previous notions of what is a recession and what pushes us into recession, and would be very interested in hearing what you think.

To be more specific, let me use European developments, which I think are even more thought-provoking from this perspective than US developments. Take an extreme example of Czechia, which combines following facts:

- GDP has contracted for two quarters in a row, each time around 0.3% non-annualized. It is still below its pre-pandemic peak.

- Consumption has contracted for 5 quarters in a row, cumulatively 7.6%.

- Fixed investment has decreased in last quarter as well, albeit after strong recovery throughout the previous year and a half.

- The reason why GDP did not drop more is because net exports surged from their extremely low values reached during the pandemic period. In last quarter government consumption also helped a lot.

- Despite all the weakness, labor market is tight, with unemployment rate close to its pre-pandemic historical lows (in case you don’t know, it is ridiculously-sounding low at 2.1%), and employment continuing to grow.

(This as of March; more recent data continued in these trends, albeit GDP overall increased a tad bit. Also, Germany is going through something similar, albeit at much smaller scale).

It feels like this combination just does not fit in together in terms of standard macroeconomics – if you would tell me only about consumption (2) I would say the country has to be in recession, but investment (3) and labor market (5) are clearly saying no recession. If it would be just labor market, then I could accept that it is case of labor hoarding distorting the picture, but investment also remaining robust is just hard to reconcile with recession.

So I was wondering in what way, if any, did the last update your beliefs about “what is a recession and what pushes us into recession” in the light of the puzzling macroeconomic data of last year or so…

P.S.: In case you want to read more on the case of Czechia, or my take on what it all means, I had a blog post few months back:

https://kamilkovar.substack.com/p/it-or-isnt-it-recession-on-regular

My way of reconciling the data with my mental models is that got real shocks pushing us into RBC-style recession, but for whatever reason we did not get the typical demand shocks that lead to a more standard recession.”

TC again: Worth a ponder!

Monday assorted links

1. Why do many people find slow motion appealing?

2. Canine markets in everything, Austin edition. And the hotel version (NYT).

3. News stripped of all hype and emotion, by AI. And new tool for co-authoring long form articles with AI.

5. Everleigh? Nova? Good to see that “Tyler” is dropping in popularity. Rising and falling baby names.

6. Why you should visit Ravenna.

7. The Straussian that is Magnus Carlsen (WSJ). Thanos!

More persistence and propagation than you might think?

Macroeconomic cycles are much more self-reinforcing and correspondingly resistant to shocks and hence longer-lasting than what is commonly thought…

The key idea is that economic developments feature strong endogenous propagation mechanisms which yield endogenous cyclical behavior ala limit cycles.

And:

What is at heart of this behavior? There are three factors that the authors point towards. First is strategic complementarity between economic agents’ behavior, such as the fact that firms want to invest when other firms are investing. Second, you need inertia in individual behavior, so that rapid changes in behavior are costly. And finally, you need dependence on some stock variable such as aggregate amount of capital or durable goods. All of these requirements seem very realistic assumption about the real world.

What are the implications of such model? Among other things this means that in certain periods of time the economy is very robust to negative shocks, because these shocks do not have the power to overturn the forces (resulting from the strategic complementarity between agents) that are pushing economic activity higher. They might push us slightly lower for some period of time, but they don’t turn things completely around. And once their effect fades the economy continues in its previous trajectory. In a sense, this view suggests that economic cycles are more like a titanic.

It also means that there is certain dichotomy in terms of shocks. Shocks ranging in size from “small” to “large-but-not-gigantic” proportions do not change the underlying trajectory of the economy, unless we are already close to turning point in the limit cycle. Meanwhile, truly gigantic shocks, like the global financial crisis, are not just deviation from the medium-term trend defined by the limit cycle, but a change in the medium-term trend.

And in conclusion:

To summarize, the limit cycle view suggests that a powerful enough shock, such as the rebound when economies re-opened after the pandemic recession, can put us on a upward spiral, and that such spiral features such a strong self-reinforcing mechanisms that even large negative shocks cannot derail us. This in contrast to standard DSGE models that feature only relatively weak propagation of shocks, and, crucially, do not feature any medium-term cyclical behavior.

Here is much more from Kamil Kovar, a good and important post.

How much does short-run economic “DNA” persist across interruptions?

One of the current macro puzzles is that we keep on receiving good labor market reports during a time of monetary and credit tightening. Which is the missing “dark matter” variable that helps to explain this?

One general observation, stressed by Conor Sen, is simply that we don’t have real macro data or macro models for pandemics or post-pandemic recoveries. I agree, but what exactly might be the missing key variable(s)?

If we rewind to say February 2020, might there have been favorable conditions for further economic growth, conditions that implied some degree of momentum but no tendency toward a destructive Minsky moment? And were those favorable conditions somehow “frozen in amber” during the pandemic, to be thawed, taken out, and reconstituted during the recovery and subsequent growth period?

How exactly does one freeze and then thaw out initial macro conditions during a pandemic? What exactly would it be that is happening, as might be expressed in a simple model? Is there some kind of “macro accelerator” that is carried over across time? Is it a “previously processed working out of excess” that remains in place during the pandemic recovery? (One tweet by Conor, which I don’t at the moment find, seemed to raise this as one possibility.)

What else?

Saturday assorted links

1. “Schumacher family planning legal action over AI ‘interview’ with F1 great.”

2. More Brian Potter on how solar power got cheap.

3. “In a study to be published this summer, they find that the median ai expert gave a 3.9% chance to an existential catastrophe (where fewer than 5,000 humans survive) owing to ai by 2100. The median superforecaster, by contrast, gave a chance of 0.38%.” From The Economist.

4. New charter city for Nigeria? (p.s. silly header on the article). And some CCI corrections to the piece.

A Major Shock Makes Prices More Flexible and May Result in a Burst of Inflation or Deflation

From the excellent Robert E. Hall:

The US and other advanced countries suffered bursts of severe inflation in 2021 and the first half of 2022, followed by declines of inflation later in 2022, in some countries. In times of high volatility of price determinants—cost and productivity—inflation can jump upward and fall downward at high speed, contrary to the uniformly sticky behavior associated with traditional Phillips curves. This paper establishes that sectors with standard New Keynesian price stickiness are vulnerable to rapid transitions from stickiness to flexibility, as sellers elect to reset their prices and abandon anchoring. The paper shows that the cross-industry volatility of price determinants grew substantially in the inflation episode accompanying the pandemic. Volatility remained elevated even in late 2022. The logic of the New Keynesian model of the Phillips curve links inflation to volatility, because a larger fraction of sellers are pushed out of their regions of inaction when volatility is elevated. The New Keynesian Phillips curve becomes much steeper in volatile times.

Here is the full NBER working paper. I also liked these sentences from the first page:

A seller in a more volatile environment will adopt policies that involve more frequent adjustments of the seller’s price, compared to one is a less volatile environment. Consequently, prices will respond more quickly to driving forces and the relation between inflation and driving forces will be steeper.

Very likely a part of the broader inflation story.

The Inflationary Effects of Sectoral Reallocation

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented shift of consumption from services to goods. We study this demand reallocation in a multi-sector model featuring sticky prices, input-output linkages, and labor reallocation costs. Reallocation costs hamper the increase in the supply of goods, causing inflationary pressures. These pressures are amplified by the fact that goods prices are more flexible than services prices. We estimate the model allowing for demand reallocation, sectoral productivity, and aggregate labor supply shocks. The demand reallocation shock explains a large portion of the rise in U.S. inflation in the aftermath of the pandemic.

That is from a new paper by Francesco Ferrante, Sebastian Graves, and Matteo Iacoviello. From the Board of Governors, 3.5 percentage points if you had to say how much. Via Nick Timiraos.

Friday assorted links

1. David Brooks on AI (NYT). And a new AI tool for diagnosis. And what to do when you have to make a phone call in your second language. And connect Chat to your 3-D printer. And claims about Bing (speculative and unconfirmed). And Google might activate?

2. On the military potential of balloons.

3. David Wallace-Wells on why excess deaths remain high (NYT).

Friday assorted links

1. More Scott Sumner movie reviews.

2. “Why do they hate the children?” Hat tip @pmarca.

3. Apple unveils AI-voiced audiobooks. And some insights into how ChatGPT models work. And can ChatGPT do analogical reasoning without explicit training?

4. Is Garett Jones channeling the Lord of the Vineyard?

5. Self-perceived attractiveness reduces face mask-wearing intention.

6. 41% of NYC school students were chronically absent last year.

7. Was Vermeer a Jesuit? And it seems he may have used a camera obscura.

The Story of VaccinateCA

The excellent Patrick McKenzie tells the story of VaccineCA, the ragtag group of volunteers that quickly became Google’s and then the US Government’s best source on where to find vaccines during the pandemic.

Wait. The US Government was giving out the vaccines. How could they not know where the vaccines were? It’s complicated. Operation Warp Speed delivered the vaccines to the pharmacy programs and to the states but after that they dissappeared into a morass of incompatible systems.

[L]et’s oversimplify: Vials were allocated by the federal government to states, which allocated them to counties, which allocated them to healthcare providers and community groups. The allocators of vials within each supply chain had sharply limited ability to see true systemic supply levels. The recipients of the vials in many cases had limited organizational ability to communicate to potential patients that they actually had them available.

Patients then asked the federal government, states, counties, healthcare providers and community groups, ‘Do you have the vaccine?’ And in most cases the only answer available to the person who picked up the phone was ‘I don’t have it. I don’t know if we have it. Plausibly someone has it. Maybe you should call someone else.’ Technologists will see the analogy to a distributed denial of service incident, and as if the overwhelming demand was not enough of a problem, the rerouting of calls between institutions amplified the burden on the healthcare system. Vaccine seekers were routinely making dozens of calls.

This caused a standing wave of inquiries to hit all levels of US healthcare infrastructure in the early months of the vaccination effort. Very few of those inquiries went well for any party. It is widely believed, and was widely believed at the time, that this was primarily because supply was lacking, but it was often the case that supply was frequently not being used as quickly as it was produced because demand could not find it.

It turned out that the best way to get visibility into this mess was not to trace the vaccines but to call the endpoints on the phone and then create a database that people could access which is what VaccinateCA did but in addition to finding the doses they had to deal with the issue of who was allowed access.

A key consideration for us, from the first day of the effort, was recording not just which pharmacist had vials but who they thought they could provide care to. This was dependent on prevailing regulations in their state and county, interpretations of those regulations by the pharmacy chain, and (frequently!) ad hoc decision-making by individual medical providers. Individual providers routinely made decisions that the relevant policy makers did not agree comported with their understanding of the rules.

VaccinateCA saw the policy sausage made in real time in California while keeping an eye on it nationwide. It continues to give me nightmares.

California, not to mince words, prioritized the appearance of equity over saving lives, over and over and over again, as part of an explicitly documented strategy, at all levels of the government. You can read the sanitized version of the rationale, by putative medical ethics experts, in numerous official documents. The less sanitized version came out frequently in meetings.

This was the official strategy.

The unofficial strategy, the result the system actually obtained, was that early access to the vaccine was preferentially awarded based on proximity to power and to the professional-managerial class.

… The essential workers list heavily informed the vaccination prioritization schedule. Lobbyists used it as procedural leverage to prioritize their clients for vaccines. The veterinary lobby was unusually candid, in writing, about how it achieved maximum priority (1A) for veterinarians due to them being ‘healthcare workers’.

Teachers’ unions worked tirelessly and landed teachers a 1B. They were ahead of 1C, which included (among others) non-elderly people for whom preexisting severe disability meant that ‘a covid-19 infection is likely to result in severe life-threatening illness or death’. The public rationale was that teachers were at elevated risk of exposure through their occupation. Schools were, of course, mostly closed at the time, and teachers were Zooming along with the rest of the professional-managerial class, but teachers’ unions have power and so 1B it was. Young, healthy teachers quarantining at home were offered the vaccine before people who doctors thought would probably die if they caught Covid.

Now repeat this exercise up and down the social structure and economy of the United States.

…Healthcare providers were fired for administering doses that were destined to expire uselessly. The public health sector devoted substantial attention to the problem of vaccinating too many people during a pandemic. Administration of the formal spoils system became farcically complicated and frequently outcompeted administration of the vaccine as a goal.

The process of registering for the vaccine inherited the complexity of the negotiation over the prioritization, and so vulnerable people were asked to parse rules that routinely befuddled healthy professional software engineers and healthcare administrators – the state of New York subjected senior citizens to a ‘51 step online questionnaire that include[d] uploading multiple attachments’!

That isn’t hyperbole! New York meant to do that! On purpose!

Lives were sacrificed by the thousands and tens of thousands for political reasons. Many more were lost because institutions failed to execute with the competence and vigor the United States is abundantly capable of.

…The State of California instituted a policy of redlining in the provision of medical care in a pandemic to thunderous applause from its activist class and medical ethics experts….Residency restrictions were pervasively enforced at the county level and frequently finer-grained than that. A pop-up clinic, for example, might have been restricted to residents of a single zip code or small group of zip codes.

All people are equal in the eyes of the law in California, but some people are . . . let’s politely say ‘administratively disfavored’.

The theory was, and you could write down this part of it, disfavored potential patients might use social advantages like better access to information and transportation to present themselves for treatment at locations that had doses allocated for favored potential patients. This part of the theory was extremely well-founded. Many people were willing to drive the length and breadth of California for their dose and did so.

What many wanted to do, and this is the part that they couldn’t write down, is deny healthcare to disfavored patients. Since healthcare providers are public accommodations in the state of California, they are legally forbidden from discriminating on the basis of characteristics that some people wanted to discriminate on. So that was laundered through residency restrictions.

Many more items of interest. I didn’t know this incredibly fact about the Biden adminsitratins Vaccines.gov for example:

Pharmacies through the FRPP had roughly half of the doses; states and counties had roughly the other half (sometimes administered at pharmacies, because clearly this isn’t complicated enough yet). You would hope that state and county doses were findable on Vaccines.gov. It was going to be the centerpiece of the Biden administration’s effort to fix the vaccine finding problem and take credit for doing so.

…Since the optics would be terrible if America appeared to serve some states much better than others on the official website that everyone would assume must show all the doses, no state doses, not even from states that would opt in, would be shown on it, at least not at the moment of maximum publicity. Got that?

A good point about America.

We also benefited from another major strength of America: You cannot get arrested, jailed, or shot for publishing true facts, even if those facts happen to embarrass people in positions of power. Many funders wanted us to expand the model to a particular nation. In early talks with contacts there in civil society, it was explained repeatedly and at length that a local team that embarrassed the government’s vaccination rollout would be arrested and beaten by people carrying guns. This made it ethically challenging to take charitable donations and try to recruit that team.

Many more points of interest about the process of running a medical startup during a pandemic. Read the whole thing.

What rises and falls in status through the FTX story?

More than one MR reader has requested this post, so here goes:

Rises

- Common-sense morality

- Common-sense investing rules

- American corporate governance

- Boards, and nervousness about related-party transactions

- Coinbase

- Seen as stodgy and bloated for much of the past year. But run in the US, listed in the US, and properly segregating customer funds.

- Elon Musk’s ability to judge character

- Vitalik and Ethereum

- Circle, Kraken, and Binance

- Anthony Trollope, Herman Melville, and the 19th century novel. Books more generally.

- U.S. regulation of domestic exchanges – it is one of the things we seem to do best, and they created little trouble during 2008-2009, or for that matter during the pandemic

- CBDC, and sadly so

- Crypto forensics

- Twitter and weird anon accounts

- When would the trouble have been exposed if not for Twitter? And much of the best coverage came from accounts with names like Autism Capital.

- Some critics (like Aaron Levie), too.

- Bitcoin

- After a cataclysm for the crypto sector, it’s down about 15% over the past month. That’s less than the S&P 500 lost during the worst month of the GFC.

Falls

- Effective Altruism

- A totalizing worldview that has enabled some undesirable weirdness in different places.

- Valorizing “scope sensitivity” and expected value leads people violently astray.

- Being unmarried (and male) above the age of 30

- Being on the cover of magazines

- And if you see “the next Buffett”, run.

- Appearing with blonde models

- Buying Super Bowl ads and sponsoring sports and putting your name on arenas

- “Earn to give” as both a concept and a phrase

- Mrs. Jellyby

- The concept of self-custody

- Weird locations for corporate offices

- Venture capital

- Our ability to see crazes for what they are in the moment

- This is not just, or even mainly, about crypto

- Drugs

- Adderall and modafinil, perhaps stronger stuff also played a role.

- The children of influential faculty

- Do they grow up witnessing low-accountability systems and personality behaviors?

What else? I thank several individuals for their assistance with this post.

Long Social Distancing

From Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis:

More than ten percent of Americans with recent work experience say they will continue social distancing after the COVID-19 pandemic ends, and another 45 percent will do so in limited ways. We uncover this Long Social Distancing phenomenon in our monthly Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes. It is more common among older persons, women, the less educated, those who earn less, and in occupations and industries that require many face-to-face encounters. People who intend to continue social distancing have lower labor force participation – unconditionally, and conditional on demographics and other controls. Regression models that relate outcomes to intentions imply that Long Social Distancing reduced participation by 2.5 percentage points in the first half of 2022. Separate self-assessed causal effects imply a reduction of 2.0 percentage points. The impact on the earnings-weighted participation rate is smaller at about 1.4 percentage points. This drag on participation reduces potential output by nearly one percent and shrinks the college wage premium. Economic reasoning and evidence suggest that Long Social Distancing and its effects will persist for many months or years.

That is a new NBER working paper.