Results for “paul romer” 134 found

Paul Romer’s blog

Chartercities.org, it's just getting started. For the pointer I thank Mike Gibson.

Paul Romer update

David Warsh reports that Romer has resigned from Stanford and he has a plan to change the world:

…[he has] a scheme to persuade nations around the world to adopt “special administrative zones,” managed in many cases by foreign governments, based on the model of Hong Kong, which, for 150 years, was administered from afar by Britain. “Hong Kong was the most successful economic development in history,” says Romer. The rules developed there over time were codified, copied and installed by the Chinese government in four special zones along the coast in the 1980s; the experiment worked so well that the system was adopted country wide.

Romer presented a rehearsal version of his ideas at a seminar in May at San Francisco’s Long Now Foundation. You can watch Romer’s A Theory of History, With an Application online (or just this five-minute snippet), or read Long Now co-founder Stewart Brand’s summary of the talk. It costs $995 to watch in real-time, along with all the rest of the proceedings, the 18-minute version that Romer plans to deliver this week in England. But presumably the talk will be available online soon enough; the TED forum bills itself as offering “riveting talks by remarkable people, free to the world.” And, according to Brand, Romer plans to open an Institute with a website this summer.

I'm all for this idea (how would the Swiss do in Nigeria?), but I fear that Hong Kong is a cautionary tale in the other direction. Due mostly to the pressures of nationalism, the world's most successful development experiment was ended without a second thought. And its initiation was backed by brute colonial force. Which country is most likely to allow another country to manage part of its territory in a new experiment?

Interview with Paul Romer on Mauritius

Via Mark Thoma, here is an interview with Paul Romer about growth in Mauritius. One question is how much Romer’s growth theory was needed to generate this advice. Second, I am surprised how little attention he gives to Mauritius being a small country. I don’t think that country size makes the advice much different, but perhaps expectations should be adjusted. Most small countries aren’t well-diversified and their growth rates depend heavily on real shocks. Singapore is an exception, most of all because its citizenry is obsessed with accumulating human capital and thus it depends upon a general flow of foreign capital rather than specific sectors. I don’t see harm in Mauritius trying to follow this same path but I wouldn’t expect them to succeed to a comparable degree.

Speaking of small countries, Fred Sautet has an interesting blog post on what happened to the New Zealand reforms. Since the reforms starting in the 1980s, New Zealand has had excellent economic policies, probably better than Mauritius can expect to implement. But New Zealand has not had stunning rates of economic growth. A big part of the answer is simply that New Zealand still depends on the demands for dairy and agriculture. Yes, many parts of the country are booming but the worldwide demand for commodities is a big part of the reason why. The deregulation of agriculture helped but without rising food prices growth would be lower yet. Earlier, it was Britain’s removal of imperial preference in 1972 that sent the country tumbling over the edge in the first place. Yes freedom is still better but in general small countries are less of an "economic laboratory" than we might think. Conversely, while there are some good explanations for "the Irish miracle," a small country with a few million people can with good luck grow quite rapidly.

Just think about the determinants of your own family income; probably for most years policy changes are not #1 on the list. A country of 1.2 million people, such as Mauritius, is more diversifed than your family, but not as much more diversified as you might think. When it comes to real factors, Say’s Law does hold. Demand for your labor depends on the production decisions of 300 million mostly wealthy and often quite diversified Americans. That offers your income a great deal of protection, relative to what suppliers on Mauritius can expect.

Paul Romer on economic growth

EconTalk podcast, with Russ Roberts. I’ve yet to hear it, but the interviewer and interviewee make it self-recommending.

Romer on Urban Growth

Here’s one bit from an excellent interview of Paul Romer on urban development:

Q. How are economics and planning and development of cities related each other?

Urban Expansion is an exception to the usual rule that an economy does not need a plan. Creating new built urban area requires a plan for the public space that will be used for mobility (sidewalks, bus lanes, bike lanes, auto lanes …) and for parks. At a minimum, this plan should provide for a network of arteries big enough to allow bus travel and dense enough that no location is more than 0.5 km from such an artery. This is the only thing that needs to be planned up front for land that is not yet developed. Everything else can wait. But if informal development comes first, it is too late. The area will never have enough public space to allow successful urban development.

I think Romer is correct. What surprised me most when studying Gurgaon in India was that despite strong demand, there wasn’t a lot of common infrastructure being built. The transaction costs of ex-post planning were simply too high.

In addition to transport arteries, I would also mention the importance of setting aside space and access points for sewage, electricity, and information arteries. It’s not even necessary that government provide these services or even the plan itself (private planning of large urban areas is also possible) but a plan has to be made. By reserving space for services in advance of development, developers and residents can greatly improve coordination and maximize the value of a city.

A simple, minimal urban plan is analogous to the rules of the game.

The Paul vs. Paul debate

That’s Ron Paul vs. Paul Krugman, the video and transcript is here, here are a few comments under the fold…

1. RP: I don’t understand RP’s claim “I want a natural rate of interest.” Even gold standards allow for monetary influences (distortions? …depends on your point of view) on interest rates. RP has not fully absorbed Myrdal (1930) and Sraffa (1932).

2. K’s response to RP: Numerous good points, but Christie Romer (!) has shown that economic volatility was not higher before WWII. (Somehow that’s one Romer paper which isn’t discussed so much anymore.) That’s a major hole in K’s argument. Relative to the evidence, he is overreaching when a more modest point would suffice.

3. RP: The transcript may be garbled here. In any case, the Fisher effect is imperfect and so inflation does to some extent tax savings, also through interaction effects with the tax system. That said, I don’t see that two to four percent inflation has unacceptable costs, especially when AD is otherwise weak. On Diocletian, via Matt, here is a good recent paper.

4. K’s response: Modern liberals have a bad and selective case of 1950s nostalgia. Krugman is significantly overrating the role of policy here. More overreaching. He should stick to analyzing the “no bailout in 2008-2009” scenario, and how much worse it would have been, including for RP’s preferred ends. On earlier time periods, he should reread his own writings from around the time of The Age of Diminished Expectations. There is very little in The Conscience of a Liberal which actually trumps or overturns the earlier book and its focus on productivity rather than politics.

5. RP: I don’t understand his discussion of the liquidation of debt. Perhaps the transcript is garbled again. He is correct that the massive spending cuts which followed WWII brought no depression but rather the economy boomed. Keynesians have a hard time explaining that episode without recourse to Ptolemaic epicycles, etc., or without admitting the importance of real shocks.

6. K’s response: On Friedman, correct and on target. That said, K’s blogged claim today — that Friedman misrepresented his own views — lacks a quotation or citation altogether; furthermore it is contradicted by this excerpt from Free to Choose, which was Milton at his most popular but still he represented the truth correctly (ignore the heading, which is not from Friedman). K won’t address the WWII point, although he could if he revisited his earlier writings on changing rates of productivity growth.

7. RP’s response: The decline in the value of the dollar since 1913, or whenever, has not been a major economic cost. No one has had such a long planning horizon, for one thing. We don’t see much indexation, for another.

8. RP on the Fed: If we had “real monetary competition,” dollars still would reign supreme. Who now is opening up U.S. bank accounts in other currencies? Or using gold indexing? It is allowed.

9. K’s response: Mostly I agree, though it is odd to think of shadow banking as “currency competition.” It is more akin to “not explicitly regulated banking, with stochastic under-capitalization, and with bailouts in the background and largely driven by regulatory arbitrage.” That makes it less of a counter to RP than PK is suggesting.

10. RP: Equating inflation with “fraud” is an excessive moralization of the issue. The point remains that gentle inflation is usually a good thing, and that the money supply under free banking, or a gold standard, would be excessively pro-cyclical. The best shot is to hope that a natural monopoly private clearinghouse would institute nominal gdp targeting in terms of levels and perhaps “targeting the forecast” too.

11. The exchange about Bernanke: I don’t know whether Krugman literally has “printing money” in mind, so this is hard to interpret. They are stuck in the vernacular, when a more precise economic language would allow for more targeted commentary.

12. PK: Demographics, plus government gridlock and lower productivity growth, make a higher debt-gdp ratio more problematic than Krugman admits.

13. RP: Polemics from RP.

14. K’s response. Very short. But if he likes the market so much, why does he so often seem to be pushing for much higher taxation and higher government revenue? I understand why he wants single payer, but he also seems to favor direct government provision of health care itself.

15. RP: The discussion of debt doesn’t make sense, though it is correct to argue that eight percent measured unemployment underestimates the depth of our labor market problems. I fear, though, that he may be holding an exaggerated version of this point. U6 matters, but it should not be taken as the correct measure of unemployment.

16. RP: Seigniorage isn’t a major source of government revenue, and in general it is worth thinking about why corporate profits are so high and why the stock market, at least in recent times, has done OK. Is it really all about policy uncertainty? Lots of polemic here. Still, RP raises the point that Fed purchases of T-Bills may be helping to keep rates artificially low. This remains unproven, but it is also unrebutted.

17. RP (again): There is no credible alternative to the dollar as reserve currency today. On Spain, it is nonetheless a good point that spending cuts in a dysfunctional economy don’t help very much if at all.

More RP: Doesn’t PK get to speak again? Did Austerians suddenly cut the funding for his part of the transcript? (Had I watched the video, I wouldn’t have had time to write this post.) In any case, pegging the dollar to gold in an era of commodity price inflation would be a disaster and lead to massive deflationary pressures or more likely a complete abandonment of the gold peg rather quickly.

In sum: There were too many times when RP simply piled polemic points on top of each other and stopped making a sequential argument. He overrates the costs of inflation, including in the long term, and for a believer in the market finds it remarkably non-robust in response to bad monetary policy. Still, given that Krugman is a Nobel Laureate in economics, and Paul a gynecologist, the score could have been more lopsided than in fact it was.

In Conversation with Próspera CEO Erick Brimen & Vitalia Co-Founder Niklas Anzinger

During my visit to Prospera, one of Honduras’ private governments under the ZEDE law, I interviewed Prospera CEO Erick Brimen and Vitalia co-founder Niklas Anzinger. I learned a lot in the interview including the real history of the ZEDE movement (e.g. it didn’t begin with Paul Romer). I also had not fully appreciated the power of reciprocity stacking.

Companies in Prospera have the unique option to select their regulatory framework from any OECD country, among others. Erick Brimen elaborated in the podcast how this enables companies to do normal, OECD approved, things in Prospera which literally could not be done legally anywhere else in the world.

…so in the medical world for instance you have drugs that are approved in some countries but not others and you have medical practitioners that are licensed in some countries but not the others and you have medical devices approved in some countries but not others and there’s like a mismatch of things that are approved in OECD countries but there’s no one location where you can say hey if they’re approved in any country they’re approved here. That is what Prosper is….Our hypothesis is that just by doing that we can leapfrog to a certain extent and it’s got nothing to do with the wild west or doing weird things.

…so here so you can have a drug approved in the UK but not in the US with a doctor licensed in the US but not in the UK with a medical device created in Israel but not yet approved by the FDA following a procedure that has been say innovated in Canada, all of that coming together here in Prospera.

Retrospective look at rapid Covid testing

To be clear, I still favor rapid Covid tests, and I believe we were intolerably slow to get these underway. The benefits far exceed the costs, and did earlier on in the pandemic as well.

That said, with a number of pandemic retrospectives underway, here is part of mine. I don’t think the strong case for those tests came close to panning out.

I had raised some initial doubts in my podcasts with Paul Romer and also with Glen Weyl, mostly about the risk of an inadequate demand to take such tests. I believe that such doubts have been validated.

Ideally what you want asymptomatic people in high-risk positions taking the tests on a frequent basis, and, if they become Covid-positive, learning they are infectious before symptoms set in (remember when the FDA basically shut down Curative for giving tests to the asymptomatic? Criminal). And then isolating themselves. We had some of that. But far more often I witnessed:

1. People with symptoms taking the tests to confirm they had Covid. Nothing wrong with that, but it leads to a minimal gain, since in so many cases it was pretty clear without the test.

2. Various institutions requiring tests for meet-ups and the like. These tests would catch some but not all cases, and the event still would turn into a spreader event, albeit at a probably lower level than otherwise would have been the case.

3. Nervous Nellies taking the test in low-risk situations mainly to reassure themselves and others. Again, no problems there but not the highest value use either.

So the prospects for mass rapid testing — done in the most efficacious manner — were I think overrated.

I recall the summer of 2022 in Ireland, which by the way is when I caught Covid (I was fine, though decided to spend an extra week in Ireland rather than risk infecting my plane mates). Rapid tests were available everywhere, and at much lower prices than in the United States. Better than not! But what really seemed to make the difference was vaccines. The availability of all those tests did not do so much to prevent Covid from spreading like a wildfire during that Irish summer. Fortunately, deaths rose but did not skyrocket.

The well-known Society for Healthcare Epidemiology just recommended that hospitals stop testing asymptomatic patients for Covid. You may or may not agree, but that is a sign of how much status testing has lost.

Some commentators argue there are more false negatives on the rapid tests with Omicron than with earlier strains. I haven’t seen proof of this claim, but it is itself noteworthy that we still are not sure how good the tests are currently. That too reflects a lower status for testing.

Again, on a cost-benefit basis I’m all for such testing! But I’ve been lowering my estimate of its efficacy.

Our Regulatory State Isn’t Learning

Delta is the fourth wave of covid, and amazingly the US policy response is even more irresolute than the first time around. Our government is like a child, sent next door to get a cup of sugar, who gets as far as the front stoop and then wanders off following a puppy.

The policy response is now focused on the most medically ineffective but most politically symbolic step, mask mandates. An all-night disco in Provincetown turns in to a superspreader event so… we make school kids wear masks in outdoor summer camps? Masks are several decimal places less effective than vaccines, and less effective than “social distance” in the first place.* Go to that all night disco, unvaccinated, but wear a mask? Please.

If we’re going to do NPI (non pharmaceutical interventions), policy other than vaccines, the level of policy and public discussion has tragically regressed since last summer. Last summer, remember, we were all talking about testing. Alex Tabarrok and Paul Romer were superb on how fast tests can reduce the reproduction rate, even with just voluntary isolation following tests. Other countries had competent test and tracing regimes. Have we built that in a year? No. (Are we ready to test and trace the next bug? Double no.)

What happened to the paper-strip tests you could buy for $2.00 at Walgreen’s, get instant results, and maybe decide it’s a bad idea to go to the all night dance party? Interest faded in November. (Last I looked, the sellers and FDA were still insisting on prescriptions and an app sign up, so it cost $50 and insurance “paid for” it.) What happened to detailed local data? Did anyone ever get it through the FDA’s and CDCs thick skulls that even imperfect but cheap and fast tests can be used to slow spread of disease?

…And then we indulge another round of America’s favorite pastime, answers in search of a question. Delta is spreading, so… extend the renter eviction moratorium. People who haven’t paid rent in a year can stay, landlords be damned.

All true. I got dispirited on testing. It’s insane that we don’t have cheap, rapid testing and good ventilation ready for a new school year. As I wrote about earlier, even the American Academy of Pediatrics is shouting from the rooftops that the FDA is deadly slow. The eviction moratorium is a sick joke. Just a backhanded way to redistribute wealth without a shred of justice or reason. Disgusting.

Here’s one more bit (but read the whole thing there is more.)

To learn from the mistakes, and institutionalize better responses would mean to admit there were mistakes. One would think the grand blame-Trump-for-everything narrative would allow us to do that, but the mistakes are deeply embedded in the bureacracies of the administrative state. Unlike bad admirals in WWII, nobody less than Trump himself has lost their job over incompetent covid response. The institutions have an enormous investment in ratifying that they did the best possible job last time. So, as in so many things (financial bailouts!) we institutionalize last time’s mistakes to keep those who made them in power in power — which means we do not learn from mistakes.

Hearing: “Vaccinations and the Economic Recovery”

I will be testifying to the JEC of Congress today at 2:30 pm est.

Witnesses:

Dr. Paul Romer

Nobel Prize Winning economist and NYU Professor

New York, NY

Dr. Céline Gounder, MD, ScM, FIDSA

Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine & Infectious Diseases, NYU School of Medicine & Bellevue Hospital

CEO of Just Human Productions

New York, NY

Dr. Alexander Tabarrok

Bartley J. Madden Chair in Economics at the Mercatus Center and Professor of Economics George Mason University

Fairfax, VA

Dr. Belinda Archibong

Assistant Professor, Economics

Barnard College, Columbia University

New York, NY

Link here.

In praise of Alex Tabarrok

Here’s a question I’ve been mulling in recent months: Is Alex Tabarrok right? Are people dying because our coronavirus response is far too conservative?

I don’t mean conservative in the politicized, left-right sense. Tabarrok, an economist at George Mason University and a blogger at Marginal Revolution, is a libertarian, and I am very much not. But over the past year, he has emerged as a relentless critic of America’s coronavirus response, in ways that left me feeling like a Burkean in our conversations.

He called for vastly more spending to build vaccine manufacturing capacity, for giving half-doses of Moderna’s vaccine and delaying second doses of Pfizer’s, for using the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, for the Food and Drug Administration to authorize rapid at-home tests, for accelerating research through human challenge trials. The through line of Tabarrok’s critique is that regulators and politicians have been too cautious, too reluctant to upend old institutions and protocols, so fearful of the consequences of change that they’ve permitted calamities through inaction.

Tabarrok hasn’t been alone. Combinations of these policies have been endorsed by epidemiologists, like Harvard’s Michael Mina and Brown’s Ashish Jha; by other economists, like Tabarrok’s colleague Tyler Cowen and the Nobel laureates Paul Romer and Michael Kremer; and by sociologists, like Zeynep Tufekci (who’s also a Times Opinion contributor). But Tabarrok is unusual in backing all of them, and doing so early and confrontationally. He’s become a thorn in the side of public health experts who defend the ways regulators are balancing risk. More than one groaned when I mentioned his name.

But as best as I can tell, Tabarrok has repeatedly been proved right, and ideas that sounded radical when he first argued for them command broader support now. What I’ve come to think of as the Tabarrok agenda has come closest to being adopted in Britain, which delayed second doses, approved the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine despite its data issues, is pushing at-home testing and permitted human challenge trials, in which volunteers are exposed to the coronavirus to speed the testing of treatments. And for now it’s working: Britain has vaccinated a larger percentage of its population than the rest of Europe and the United States have and is seeing lower daily case rates and deaths.

The problem with rapid testing was always on the demand side

The U.S. government distributed millions of fast-acting tests for diagnosing coronavirus infections at the end of last year to help tamp down outbreaks in nursing homes and prisons and allow schools to reopen.

But some states haven’t used many of the tests, due to logistical hurdles and accuracy concerns, squandering a valuable tool for managing the pandemic. The first batches, shipped to states in September, are approaching their six-month expiration dates.

At least 32 million of the 142 million BinaxNOW rapid Covid-19 tests distributed by the U.S. government to states starting last year weren’t used as of early February, according to a Wall Street Journal review of their inventories…

“The demand has just not been there,” said Myra Kunas, Minnesota’s interim public health lab director.

…the tests are piling up in many states, the Journal found.

Here is more from Brianna Abbott and Sarah Krouse at the WSJ. You may recall the discussions of demand-side issues from my CWTs with Paul Romer and Glen Weyl. The envelope theorem remains underrated.

Are Nobel Prizes worth less these days?

It would seem so, now there are lots of them, here is one part of my Bloomberg column:

The Nobel Peace Prize this year went to the World Food Programme, part of the United Nations. Yet the Center for Global Development, a leading and highly respected think tank, ranked the winner dead last out of 40 groups as measured for effectiveness. Another study, by economists William Easterly and Tobias Pfutze in 2008, was also less than enthusiastic about the World Food Programme.

The most striking feature of the award is not that the Nobel committee might have gotten it wrong. Rather, it is that nobody seems to care. The issue has popped up on Twitter, but it is hardly a major controversy.

I also noted that the Nobel Laureates I follow on Twitter, in the aggregate, seem more temperamental than the 20-year-olds (and younger) that I follow. Hail Martin Gurri!

And this:

The internet diminishes the impact of the prize in yet another way. Take Paul Romer, a highly deserving laureate in economics in 2018. To his credit, many of Romer’s ideas, such as charter cities, had been debated actively on the internet, in blogs and on Twitter and Medium, for at least a decade. Just about everyone who follows such things expected that Romer would win a Nobel Prize, and when he did it felt anticlimactic. In similar fashion, the choice of labor economist David Card (possibly with co-authors) also will feel anticlimactic when it comes, as it likely will.

Card with co-authors, by the way, is my prediction for tomorrow.

Monday assorted links

1. Might changes in proton density, spurred by solar wind, predict earthquakes? If true, this would really be something.

2. Violates Godwin’s Law right upfront anyway speak for yourself! I genuinely find such hostile intentions difficult to understand.

3. Will a growth drug undermine “dwarf pride”? (NYT).

4. Robin Hanson on how and why remote work will matter.

5. Economics of the energy transition. Some subtle and underpromoted points in this one.

6. Why we can’t have good things: I am not sure how much public health experts are to blame for the problems in this article about why we don’t have home testing. The FDA won’t approve it? Do something about that! (Where is the outcry, other than from Paul Romer?) The American people aren’t ready for it? Well, are they ready for the alternatives you are proposing? Overall I found this NYT piece a depressing sign of American and perhaps also public health malaise.

7. Using banned cell phones for prison extortion by calling loved ones back home, excellent NYT piece, amazing investigative journalism.

Rapid Tests

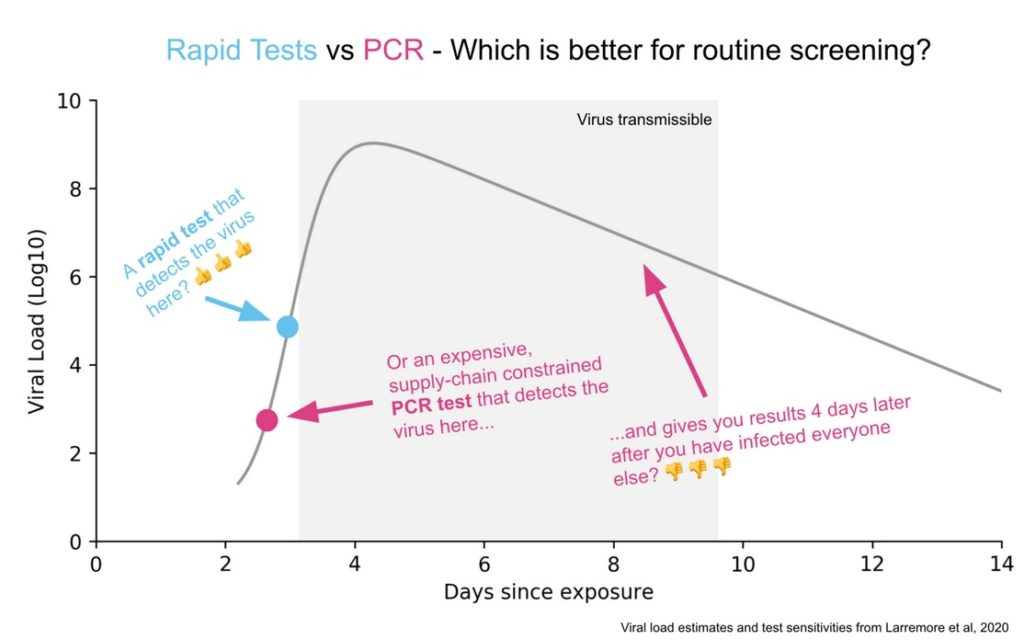

Here’s a good picture illustrating the difference between the PCR and Rapid Test. A PCR amplifies DNA and so if taken at the right time it will detect the virus before a rapid test will. But this happens when there isn’t much viral load and too little of the virus to be transmissible. Moreover, at these times, the virus is increasing rapidly so the rapid test will find the virus tomorrow. The PCR test will also pick up fragments after transmissiblity has passed which also isn’t very useful. A rapid test is very sensitive for doing what it is supposed to do, identifying periods of infectiousness.

Michael Mina has done a great job promoting rapid tests and I do think we are beginning to see some recognition of the difference between infected versus infectious and the importance of testing for the latter. What is frustrating is how long it has taken to get this point across. Paul Romer made all the key points in March! (Tyler and myself have also been pushing this view for a long time).

In particular, back in March, Paul showed that frequent was much more important than sensitive and he was calling for millions of tests a day. At the time, he was discounted for supposedly not focusing enough on false negatives, even though he showed that false negatives don’t matter very much for infection control. People also claimed that millions of tests a day was impossible (Reagents!, Swabs!, Bottlenecks!) and they weren’t impressed when Paul responded ‘throw some soft drink money at the problem and the market will solve it!’. Paul, however, has turned out be correct. We don’t have these tests yet but it is now clear that there is no technological or economic barrier to millions of tests a day.

Go yell at your member of Congress.