Results for “politics isn't about policy” 53 found

Sentences to ponder

Stunningly, the postponement of marriage and parenting — the factors that shrink the birth rate — is the very best predictor of a person’s politics in the United States, over even income and education levels, a Belgian demographer named Ron Lesthaeghe has discovered. Larger family size in America correlates to early marriage and childbirth, lower women’s employment, and opposition to gay rights — all social factors that lead voters to see red.

That is Lauren Sandler. Here is more, hat tip to Steve Sailer (and David Brooks). And as Robin Hanson would say, “politics isn’t about policy.”

Assorted links

1. Review of the new Chris Hayes book.

2. Garett Jones on speed bankruptcy (pdf).

3. The politics of Obama vs. Romney; politics isn’t about policy!

4. NYT presents 32 innovations that will change our world; are you impressed by their list? I like this one:

A team of Dutch and Italian researchers has found that the way you move your phone to your ear while answering a call is as distinct as a fingerprint. You take it up at a speed and angle that’s almost impossible for others to replicate. Which makes it a more reliable password than anything you’d come up with yourself. (The most common iPhone password is “1234.”) Down the line, simple movements, like the way you shift in your chair, might also replace passwords on your computer. It could also be the master key to the seven million passwords you set up all over the Internet but keep forgetting.

5. Are economics Ph.D programs teaching the right material?

6. More Paul Krugman on science fiction.

Warn people about two things

One problem with disclosure regulation is that people grow accustomed to the warnings and caveats and their eyes glaze over. They stop paying attention.

So let’s say you are the Über-regulator. You get to warn people about two things. Once.

Of course they may not listen to you at all, but let’s assume you have enough credibility from your political post to be given half an hour on network TV and subsequent extensive coverage and commentary on blogs and Twitter. That said, especially useful warnings, such as “You’re not as smart as you think” are perhaps especially likely to be ignored. “Honor They Superior!” is perhaps also a non-starter, though you may try it if you wish.

Which two things do you pick for your warning?

“Driving is dangerous”

“Fight nuclear proliferation.”

“Don’t let your kid near a bucket.”

“Politics isn’t about policy.”

“Beware the Ides of March!”

“Some people out there suck!”

The correct answer is not obvious. And what does this imply about regulation more generally?

I thank Bryan Caplan for a useful conversation on this topic.

David Brooks on the new Charles Murray book

Roughly 7 percent of the white kids in the upper tribe are born out of wedlock, compared with roughly 45 percent of the kids in the lower tribe. In the upper tribe, nearly every man aged 30 to 49 is in the labor force. In the lower tribe, men in their prime working ages have been steadily dropping out of the labor force, in good times and bad.

People in the lower tribe are much less likely to get married, less likely to go to church, less likely to be active in their communities, more likely to watch TV excessively, more likely to be obese…

It’s wrong to describe an America in which the salt of the earth common people are preyed upon by this or that nefarious elite. It’s wrong to tell the familiar underdog morality tale in which the problems of the masses are caused by the elites.

The truth is, members of the upper tribe have made themselves phenomenally productive. They may mimic bohemian manners, but they have returned to 1950s traditionalist values and practices. They have low divorce rates, arduous work ethics and strict codes to regulate their kids.

Members of the lower tribe work hard and dream big, but are more removed from traditional bourgeois norms. They live in disorganized, postmodern neighborhoods in which it is much harder to be self-disciplined and productive.

Remember when “rage” used to mean “Radical Alternatives to Government Enterprise”? Murray’s book will bring rage of a different kind, because it strikes rather directly at how political views are based on emotional feelings about the deserved status of various social groups (RH: “Politics isn’t about policy.”) Here is more. If you are wondering, my copy of the book arrives today. Perhaps my review will consider whether economic forces are driving the social ones, or vice versa.

Assorted links

2. “…he knows if you’ve been bad or good…”

4. The political economy of shale gas in Poland, very good short essay.

5. Politics isn’t about policy, installment #1237.

Assorted links

In case you had forgotten

SOX [Sarbanes-Oxley] was sold as the way to prevent future market bubbles and crashes.

That’s Larry Ribstein reminding us. And here is Arnold Kling reminding us:

A Central Banker should stand up to fear-mongering. Even when it comes from a Treasury Secretary.

And here is Robin Hanson reminding us of his favorite lessons:

Medicine isn’t about Health

Consulting isn’t about Advice

School isn’t about Learning

Research isn’t about Progress

Politics isn’t about Policy

Trump’s threat to let Putin invade NATO countries

I don’t usually blog on “candidate topics,”or “Trump topics,” but a friend of mine asked me to cover this. As you probably know, Trump threatened to let NATO countries that failed to meet the two percent of gdp defense budget obligation fend for themselves against Putin (video here, with Canadian commentary). Trump even said he would encourage the attacker.

Long-time MR readers will know I am not fond of Trump, either as a president or otherwise. (And I am very fond of NATO.) But on this issue I think he is basically correct. Yes, I know all about backlash effects. But so many NATO members do not keep up serious defense capabilities. And for decades none of our jawboning has worked.

Personally, I would not have proceeded or spoken as Trump did, and I do not address the collective action problems in my own sphere of work and life in a comparable manner (“if you’re not ready with enough publications for tenure, we’ll let Bukele take you!” or “Spinoza, if you don’t stop scratching the couch, I won’t protect you against the coyotes!”). So if you wish to take that as a condemnation of Trump, so be it. Nonetheless, I cannot help but feel there is some room for an “unreasonable” approach on this issue, whether or not I am the one to carry that ball.

Even spending two percent of gdp would not get many NATO allies close to what they need to do (and yes I do understand the difference between defense spending and payments to NATO, in any case many other countries are falling down on the job). I strongly suspect that many of those nations just don’t have effective fighting forces at all, and in essence they are standing at zero percent of gdp, even if their nominal expenditures say hit 1.7 percent. Remember the report that the German Army trained with broomsticks because they didn’t have enough machine guns? How many of those forces are actually ready to fire and fight in a combat situation? It is far from obvious that the Ukraine war — a remarkably grave and destructive event — has fixed that situation.

The nations that see no need to have workable martial capabilities at all are a real threat to NATO, and yes this includes Canada, which shares a very large de facto Arctic border with Putin, full of valuable natural resources. Even a United States led by Nikki Haley cannot do all the heavy lifting here. What if the U.S. is tied down in Asia and/or the Middle East when further trouble strikes? That no longer seems like such a distant possibility. And should Western Europe, over time, really become “foreign policy irrelevant,” relative to the more easternmost parts of NATO? That too is not good for anybody.

With or without Trump’s remarks, we are likely on a path of nuclear proliferation, starting in Poland.

People talk about threats to democracy in Poland, and I am not happy they have restricted the power of their judiciary. But consider Germany. The country has given up its energy independence, it may lose a significant portion of its manufacturing base, its earlier economic strategy was to cast its lot with Russia and China, AfD is the #2 party there and growing, and the former east is politically polarized and illiberal, among other problems. Most of all, the country has lost its will to defend itself. That is in spite of a well-educated population and a deliberative political systems that in the more distant past worked well. You can criticize Trump’s stupid provocations all you want, but unless you have a better idea for waking Germany (and other countries) up, you are probably just engaging in your own mood affiliation. On this issue, “argument by adjective” ain’t gonna’ cut it.

The best scenario is that Trump raises these issues, everyone in Canada and Western Europe screams, they clutch their pearls and are horrified for months, but over time the topic becomes more focal and more ensconced in their consciousness. Eventually more Democrats may pick up the Trump talking points, as they have done with China. Perhaps three to five years from now that can lead to some positive action. And if they are calling his words “appalling and unhinged,” as indeed they are, well that is going to drive more page views.

The odds may be against policy improvement in any case, but by this point it seems pretty clear standard diplomacy isn’t going to work. I am just not that opposed to a “Hail Mary, why not speak some truth here?” approach to the problem. Again, I wouldn’t do it, but at the margin it deserves more support than it is getting. Of course it is hard for the MSM American intelligentsia to show any sympathy for Trump’s remarks, because his words carry the implication that spending more on social welfare has an unacceptably high opportunity cost. So you just won’t find much objective debate of the issues at stake.

If you’re worried about Trump encouraging Putin, that is a real concern but the nations on the eastern flank of NATO are all above two percent, Bulgaria excepted. Maybe this raises the chance that Putin is emboldened to blow up some Western European infrastructure? Make a move against Canada in the Arctic? I still could see that risk as panning out into greater preparedness, greater deterrence, and a better outcome overall. Western Europe of course has a gdp far greater than that of Putin’s Russia. they just don’t have the right values, in addition to not spending enough on defense.

So on this one Trump is indeed the Shakespearean truth-teller, and (I hope) for the better.

The game theory of the balloons

One possibility is that the Chinese simply have been making a stupid mistake with these balloons (it is circulating on Twitter that this is not the first time they sent us a surveillance balloon — probably true).

A second possibility is that a faction internal to China wants to sabotage better relations between the U.S. and China.

A third possibility — most likely in my eyes — is that we do something comparable to them, which may or may not be exactly equivalent to a balloon. Nonetheless there is a tit-for-tat surveillance game going on, in which the two sides match each others moves, and have done so for years. The game evolves slowly, and occasionally all at once. The Chinese have been playing by the rules of the game, and the U.S. has decided to change the rules of the game. We may wish to send them a stern signal, we may wish to change broader China policy, we may think their balloons are too big and detectable for this to continue, USG might fear an internal leak, generating citizen opposition to balloon tolerance, or perhaps there simply has been a shift of factional powers within USG. Maybe some combination of those and other factors. So then USG “calls” China on the balloon, cashes in on the PR event, and simultaneously de facto announces that the old parameters of the former game are over. After all, in what is more or less a zero-sum game, why should any manifestation of said game be stable for very long? It isn’t, and it wasn’t. Now we will create a new game. A very small change in the parameters can lead to that result, and in that sense the cause of the new balloon equilibrium may not appear so significant on its own.

It was also a conscious decision when and where to shoot down the balloon.

Here is some NYT commentary, better than most pieces though it neglects our surveillance of them.

Forbidden Questions

It is extremly disturbing that major scientific organizations are forbidding the publication of research that offends some political sensibilities. Indeed, roadblocks are being put into place to even investigate some questions. Here is James Lee, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Minnesota, talking about the NIH’s restrictions on behavioural science:

A policy of deliberate ignorance has corrupted top scientific institutions in the West. It’s been an open secret for years that prestigious journals will often reject submissions that offend prevailing political orthodoxies—especially if they involve controversial aspects of human biology and behavior—no matter how scientifically sound the work might be. The leading journal Nature Human Behaviour recently made this practice official in an editorial effectively announcing that it will not publish studies that show the wrong kind of differences between human groups.

American geneticists now face an even more drastic form of censorship: exclusion from access to the data necessary to conduct analyses, let alone publish results. Case in point: the National Institutes of Health now withholds access to an important database if it thinks a scientist’s research may wander into forbidden territory. The source at issue, the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP), is an exceptional tool, combining genome scans of several million individuals with extensive data about health, education, occupation, and income. It is indispensable for research on how genes and environments combine to affect human traits. No other widely accessible American database comes close in terms of scientific utility.

My colleagues at other universities and I have run into problems involving applications to study the relationships among intelligence, education, and health outcomes. Sometimes, NIH denies access to some of the attributes that I have just mentioned, on the grounds that studying their genetic basis is “stigmatizing.” Sometimes, it demands updates about ongoing research, with the implied threat that it could withdraw usage if it doesn’t receive satisfactory answers. In some cases, NIH has retroactively withdrawn access for research it had previously approved.

…The federal government was under no obligation to assemble the magnificent database that is the dbGaP. Now that it has done so at taxpayer expense, however, it does have an obligation to provide access to that database evenhandedly—not to allow it for some and deny it to others, based on the content of their research.

Keep in mind that when science is politicized the questions that can be asked and the answers that can be given change as politics changes. Science isn’t natural–science, like free speech, democracy, and the rule of law relies on supporting universal norms of open inquiry–open questions, open questioners, open answers–but these universal norms run against our baser instincts and as such require sustaining cooperation in a prisoner’s dilemma where defection to our tribe is the dominant strategy.

Christopher DeMuth on national conservatism

I thought the recent WSJ Op-Ed by DeMuth was one of this year’s more important essays. DeMuth argues that conservatism needs a new [and also older], less libertarian, less cosmopolitan turn. Here is his core message:

When the leftward party in a two-party system is seized by such radicalism, the conservative instinct for moderation is futile and may be counterproductive. Yet many conservative politicians stick with it, promising to correct specific excesses that have stirred popular revulsion. Republicans will win some elections that way—but what will they do next? National conservatives recognize that in today’s politics, the excesses are the essence. Like Burke after 1789, we shift to opposing revolution tout court.

Why national conservatism? Have you noticed that almost every progressive initiative subverts the American nation? Explicitly so in opening national borders, disabling immigration controls, and transferring sovereignty to international bureaucracies. But it also works from within—elevating group identity above citizenship; fomenting racial, ethnic and religious divisions; disparaging common culture and the common man; throwing away energy independence; defaming our national history as a story of unmitigated injustice; hobbling our national future with gargantuan debts that will constrain our capacity for action.

The left’s anti-nationalism is another sharp break with the past.

Do read the whole thing, as they say. I cannot summarize his entire argument, but here are some points of push back:

1. It is a mistake to start by defining one’s view in opposition to some other set of views, in this case progressivism. You will end up with something limited and defensive and ultimately uninspiring.

2. Unlike many classical liberals, I’ve long made my peace with nationalism, but for pragmatic reasons. I view it as morally arbitrary, but also as the only possible solid foundation for a stably globalized world, given the psychologically collectivist tendencies of most humans. DeMuth opposes national conservatism to globalization for the most part, but strong nations and strong globalizations go together. There is talk of “global markets that eclipse the nation and divide its citizens,” but the case needs to be stronger and more specific than that. National security arguments aside (yes we Americans should produce more chips domestically), which exactly are the global markets that are eclipsing us? And is it global markets that are polarizing us? Really? Which ones exactly and how?

3. Virtually every critic of globalization wants to pick and choose. There is plenty of “globalization for me, not for thee” in these ideological arenas. (In similar fashion, I don’t quite get the Peter Thiel bitcoin > globalization point of view….crypto has been quite international pretty much from the beginning, and often at least in spirit directed against national monies.) And which exactly is the national body we are going to trust with micro-managing globalization? Some DC bureaucracy that operates as effectively as the CDC and is filled 90% or more with Democrats? From a national conservative point of view, or for that matter from my point of view, why do that?

4. For better or worse, Biden is far more of a nationalist than DeMuth makes him out to be. “Confiscating vaccine patents” is the only example given of this supposed excess cosmopolitanism, but hey just look at the allocation of those third doses, something Biden has pushed hard himself. On many matters of foreign policy, including China, the differences between Trump and Biden are tiny. And Europe isn’t exactly happy with Biden either.

5. The policy recommendations toward the end of the piece are underwhelming. Common carrier regulation to prevent Facebook from taking down controversial opinions is the first suggestion. Whether or not you agree with that proposal, the major social media companies were not doing much in the way of “take downs” as recently as ten years ago. To return to that state of affairs, but with the whole thing enforced by government (“Some DC bureaucracy that operates as effectively as perhaps the CDC and also is filled 90% or more with Democrats?”), is…uninspiring.

6. The next set of policy recommendations are “big projects” for cybersecurity and quantum computing. Again, whether or not you agree with those specific ideas, I don’t see why they need national conservatism as a foundation. You might just as easily come to those positions through a Progress Studies framework, among other views. And is a centralized approach really best for cybersecurity? How secure were the systems of the Office of Personnel Management? Doesn’t the firming up of all those soft targets require a fairly decentralized approach?

7. DeMuth refers to our “once-great” museums as deserving of revitalization. I would agree that the visual arts of painting and sculpture were more culturally central in earlier decades than today. But putting aside the National Gallery of Art in D.C. (in a state of radical decline…maybe blame the national Feds?), and the immediate problems of the pandemic, American museums are pretty awesome. MOMA for instance is far better than it used to be. If there has been a problem, it is that 9/11 made foreign loan contracts for art exhibits more difficult to pull off, in part for reasons of insurance. In other words, the contraction of globalization has hurt American museums.

8. I wonder how he feels about crypto, Web 3.0, and the Metaverse? I think it is perfectly fine to regard the correct opinions on those topics as still unsettled, but is national conservatism really such a great starting point? Aren’t we going to rather rapidly neglect the potential upside from those innovations? Shouldn’t we instead try to start by understanding the technologies, and then see if a nationalist point of view on them is going to make sense?

More generally, if you are going to do the NatCon thing, how about embracing the tech companies as America’s great national champions? Embracing them as your only hope for countering left-wing MSM? Somehow that is missing from DeMuth’s vision.

So I liked the piece, but I say it is a rearguard action, destined to fail. We need a more positive, more dynamic approach to a free society of responsible individuals, and that is probably going to mean an ongoing expansion of globalization and also a fairly new and indeed somewhat unsettled understanding of what the nation is going to consist of. What DeMuth calls “empirical libertarianism,” as he associates with Adam Smith, I still take as a better starting point.

Welcome to the Club

Ashish Jha, dean of the School of Public Health at Brown University, has had it with the FDA:

Nearly all public-health authorities in the country are urging people to get vaccines. We see the incredible results that the vaccines have had and how many lives they’re saving, and still the F.D.A. has not offered full, permanent approval of the vaccine. President Biden suggested it might take several more months. How do you understand that, or how can that be defended, if it can be?

I find it incredibly puzzling what exactly the F.D.A. is doing. The F.D.A. says that it typically takes them six months or sometimes as much as a year to fully approve a new product. And, generally, we appreciate that. There are two components to that. One is that they want to see a large amount of data, and they want to go through that carefully, and I think that’s essential. Then the second is that there’s a process, which can take a while. This is a global emergency, and while all of us want to make sure that the F.D.A. does its job, most of us also feel that just operating on standard procedures may not be the right thing to do here, and that there are things that can be sped up. Just as with the development of vaccines, we didn’t cut any corners. We did all the steps, but we did it much, much faster. The F.D.A. has to go much, much faster.

The other thing about the data—the amount of data that the vaccines have generated, the number of people who’ve been vaccinated, and the scrutiny that the data has received. I mean, my goodness, this data has been scrutinized and looked over more than—

I’d imagine it’s more than any data in modern history, right?

Any therapy, any vaccine ever. These are the most highly scrutinized medical products we have ever had, and I don’t understand what the F.D.A. is doing.

I’m pleased that Jha and others like Eric Topol are becoming frustrated with FDA delay. But take it from an OG, the FDA is doing what it has always done. What has changed isn’t the FDA but that more people are paying attention now that they have something personal at stake.

I am reminded of this story from 2016:

Mary Pazdur had exhausted the usual drugs for ovarian cancer, and with her tumors growing and her condition deteriorating, her last hope seemed to be an experimental compound that had yet to be approved by federal regulators.

So she appealed to the Food and Drug Administration, whose oncology chief for the last 16 years, Dr. Richard Pazdur, has been a man denounced by many cancer patient advocates as a slow, obstructionist bureaucrat.

He was also Mary’s husband.

…When asked specifically how his wife’s illness had changed his work at the F.D.A., Dr. Pazdur said he was intent on making decisions more quickly.

“I have a much greater sense of urgency these days,” Dr. Pazdur, 63, said in an interview. “I have been on a jihad to streamline the review process and get things out the door faster. I have evolved from regulator to regulator-advocate.”

I do hope that when the pandemic is over we don’t forget that for patients with life-threatening diseases it’s always been an emergency.

Hat tip: John Chilton.

Unmask the Vaccinated?

Ilya Somin points us to legal scholars Kevin Cope and Alexander Stremitzer who make the case that vaccine passports may be constitutional necessary:

Here’s why governments may be constitutionally required to provide a vaccine passport program for people under continuing restrictions. Under the U.S. Constitution, the government may not tread on fundamental rights unless the policy is “the least restrictive means” to achieve a “compelling” government interest. Even some rights considered nonfundamental may not be infringed without a rational or non-arbitrary reason. Before vaccines, blanket lockdowns, quarantines, and bans on things like travel, public gatherings, and church attendance were a necessary measure to slow the pandemic. The various legal challenges to these measures mostly failed—rightly, in our view. But now, a small but growing set of the population is fully vaccinated, with high efficacy for preventing transmission and success rates at preventing serious illness close to 99 percent or higher.

Facilitating mass immunity—and exempting the immunized from restrictions—is now both the least liberty-restrictive method for ending the pandemic through herd immunity and the most effective one. Imagine a fully vaccinated person whose livelihood is in jeopardy from ongoing travel or business restrictions. She might go to court and argue: “I present little or no danger to the public. So restricting my freedoms and preventing me from contributing to society and the economy isn’t rational, let alone the least restrictive means of protecting the public. Since you’re not lifting restrictions for everyone, the Constitution requires that I be exempt.”

This argument alone should be enough to justify mandating that passports be made available where COVID restrictions are still in place….

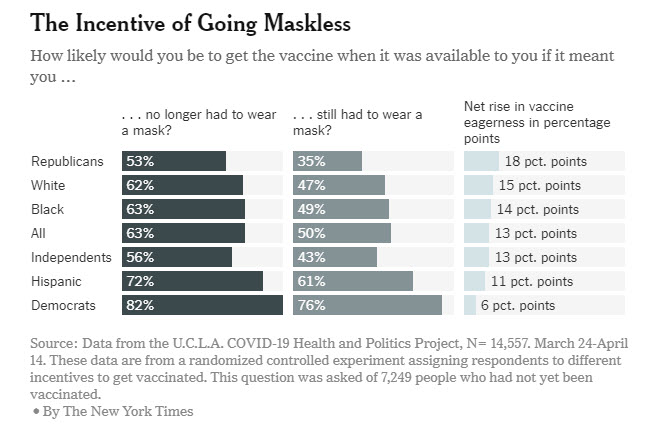

The NYTimes also notes that surveys suggest that the right to go maskless could increase vaccine take-up:

Enforcement is an issue but this might work well with universities and workplaces. See Ilya’s post for more.

Vaccines Are Not Like Emergency Rations!

According to the Guardian the First Minister of Wales explained their policy of doling out the Pfizer vaccine evenly over the next six weeks:

the Pfizer vaccine has to last us until into the first week of February.

…We won’t get another delivery of the Pfizer vaccine until the very end of January or maybe the beginning of February, so that 250,000 doses has got to last us six weeks.

That’s why you haven’t seen it all used in week one, because we’ve got to space it out over the weeks that it’s got to cover.

Bonkers! A vaccine isn’t like a limited supply of water that needs to be rationed until you arrive at the next oasis. The sooner you get the vaccine out the better! Start lowering R now! If you run out of vaccine, well scarcity is bad but running out means that at least one part of your system is working well! It’s a bad idea to kill people to make it look like you are following some sort of numerically neat plan.

One year into the pandemic and people still don’t understand vaccines or viral growth.

Hat tip: Arthur Baker.

What I’ve been reading

1. Stephen Hough, Rough Ideas: Reflections on Music and More. Scattered tidbits, about half of them very interesting, most of the rest at least decently good, mostly for fans of classical music and piano music. Should you develop the habit of warming up? Why don’t they always have a piano in the “green room”? How many recordings should you sample before trying to play a piece? What kinds of relationships do pianists develop with their page turners? That sort of thing. I read the whole thing.

2. Jeremy England, Every Life is on Fire: How Thermodynamics Explains the Origins of Living Things. A fun and readable popular science book on why life may be likely to evolve from inanimate matter: “Living things…make copies of themselves, harvest and consume fuel, and accurately predict the surrounding environment.” Who could be against that?

3. Dov H. Levin, Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions. “A fifth significant way in which the U.S. aided Adenauer’s reelection was achieved by Dulles publicly threatening, in an American press conference which took place two days before the elections, “disastrous effects” for Germany if Adenauer was not reelected.” A non-partisan, academic work, “This study is the first book-length study of partisan electoral interventions as a discrete, stand-alone phenomenon.” From 1946-2000, there were 81 discrete U.S. interventions in foreign elections, and 36 by the USSR/Russia, noting that outright conquest did not count in that data base.

4. John Kampfner, Why the Germans Do it Better: Notes from a Grown-Up Country (UK Amazon link, not yet in the USA). You should dismiss the title altogether, which is intended to provoke British people. In fact the author spends plenty of time on what is wrong with Germany, ranging from an incoherent foreign policy to the weaknesses of Frankfurt as a financial center. In any case, this is an excellent book trying to lay out and explain recent German politics and economics. It is more conventional wisdom than daring hypothesis, but the conventional wisdom is very often correct and how many people really know the conventional wisdom about Naomi Seibt anyway? Recommended, the best recent look at what is still one of the world’s most important countries.

5. David Carpenter, Henry III: 1207-1258. “No King of England came to the throne in a more desperate situation than Henry III.” The Magna Carta had just been instituted, Henry was just nine years old, and England was ruled by a triumvirate, with a very real chance that the French throne would swallow up England. This is one of those “has a lot of unfamiliar names that are hard to keep track of” books, but don’t blame Carpenter for that. In terms of scholarly contribution it stands amongst the very top books of the year. And yes there was already a Wales back then. They also started building Westminster Abbey under Henry’s reign. Here are some of the origins of state capacity libertarianism, volume II is yet to come.

6. Elena Ferrante, The Lying Life of Adults. The last quarter of the book closes strong, so my final assessment is enthusiastic, even if it isn’t in the exalted league of her Neapolitan quadrology. It will probably be better upon a rereading, which I will do.