Results for “rapid tests” 76 found

Supply curves slope upward, Switzerland fact of the day, and how to get more tests done

Under Swiss law, every resident is required to purchase health insurance from one of several non-profit providers. Those on low incomes receive a subsidy for the cost of cover. As early as March 4, the federal health office announced that the cost of the test — CHF 180 ($189) — would be reimbursed for all policyholders.

Here is the article, that reimbursement is about 4x where U.S. levels had been. The semi-good news is that the payments to Abbott are going up:

The U.S. government will nearly double the amount it pays hospitals and medical centers to run Abbott Laboratories’ large-scale coronavirus tests, an incentive to get the facilities to hire more technicians and expand testing that has fallen significantly short of the machines’ potential.

Abbott’s m2000 machines, which can process up to 1 million tests per week, haven’t been fully used because not enough technicians have been hired to run them, according to a person familiar with the matter.

In other words, we have policymakers who do not know that supply curves slope upwards (who ever might have taught them that?).

The same person who sent me that Swiss link also sends along this advice, which I will not further indent:

“As you know, there are 3 main venues for diagnostic tests in the U.S., which are:

1. Centralized labs, dominated by Quest and LabCorp

2. Labs at hospitals and large clinics

3. Point-of-care tests

There is also the CDC, although my understanding is that its testing capacity is very limited. There may be reliability issues with POC tests, because apparently the most accurate test is derived from sticking a cotton swab far down in a patient’s nasal cavity. So I think this leaves centralized labs and hospital labs. Centralized labs perform lots of diagnostic tests in the U.S. and my understanding is this occurs because of their inherent lower costs structures compared to hospital labs. Hospital labs could conduct many diagnostic tests, but they choose not to because of their higher costs.

In this context, my assumption is that the relatively poor CMS reimbursement of COVID-19 tests of around $40 per test, means that only the centralized labs are able to test at volume and not lose money in the process. Even in the case of centralized labs, they may have issues, because I don’t think they are set up to test deadly infection diseases at volume. I’m guessing you read the NY Times article on New Jersey testing yesterday, and that made me aware that patients often sneeze when the cotton swab is inserted in their noses. Thus, it may be difficult to extract samples from suspected COVID-19 patients in a typical lab setting. This can be diligence easily by visiting a Quest or LabCorp facility. Thus, additional cost may be required to set up the infrastructure (e.g., testing tents in the parking lot?) to perform the sample extraction.

Thus, if I were testing czar, which I obviously am not, I would recommend the following steps to substantially ramp up U.S. testing:

1. Perform a rough and rapid diligence process lasting 2 or 3 days to validate the assumptions above and the approach described below, and specifically the $200 reimbursement number (see below). Importantly, estimate the amount of unused COVID-19 testing capacity that currently exists in U.S. hospitals, but is not being used because of a shortage of kits/reagents and because of low reimbursement. This number could be very low, very high or anywhere in between. I suspect it is high to very high, but I’m not sure.

2. Increase CMS reimbursement per COVID-19 tests from about $40 to about $200. Explain to whomever is necessary to convince (CMS?…Congress?…) why this dramatic increase is necessary, i.e., to offset higher costs for reagents, etc. and to fund necessary improvements in testing infrastructure, facilities and personnel. Explain that this increase is necessary so hospital labs to ramp up testing, and not lose money in the process. Explain how $200 is similar to what some other countries are paying (e.g., Switzerland at $189)

3. Make this higher reimbursement temporary, but through June 30, 2020. Hopefully testing expands by then, and whatever parties bring on additional testing by then have recouped their fixed costs.

4. If necessary, justify the math, i.e., $200 per test, multiplied by roughly 1 or 2 million tests per day (roughly the target) x 75 days equals $15 to $30 billion, which is probably a bargain in the circumstances.

5. Work with the centralized labs (e.g., Quest, LabCorp., etc.), hospitals and healthcare clinics and manufactures of testing equipment and reagents (e.g., ThermoFisher, Roche, Abbott, etc.) to hopefully accelerate the testing process.

6. Try to get other payors (e.g., HMOs, PPOs, etc.) to follow CMS lead on reimbursement. This should not be difficult as other payors often follow CMS lead.

Just my $0.02.”

TC again: Here is a Politico article on why testing growth has been slow.

Why are we letting FDA regulations limit our number of coronavirus tests?

Since CDC and FDA haven’t authorized public health or hospital labs to run the [coronavirus] tests, right now #CDC is the only place that can. So, screening has to be rationed. Our ability to detect secondary spread among people not directly tied to China travel is greatly limited.

That is from Scott Gottlieb, former commissioner of the FDA, and also from Scott:

#FDA and #CDC can allow more labs to run the RT-PCR tests starting with public health agencies. Big medical centers can also be authorized to run tests under EUA. For now they’re not permitted to run the tests, even though many labs can do so reliably 9/9 cdc.gov/coronavirus/20

Here is further information about the obstacles facing the rollout of testing. And read here from a Harvard professor of epidemiology, and here. Clicking around and reading I have found this a difficult matter to get to the bottom of. Nonetheless no one disputes that America is not conducting many tests, and is not in a good position to scale up those tests rapidly, and some of those obstacles are regulatory. Why oh why are we messing around with this one?

For the pointer I thank Ada.

The Great Barrington Plan: Would Focused Protection Have Worked?

A key part of The Great Barrington Declaration was the idea of focused protection, “allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk.” This was a reasonable idea and consistent with past practices as recommended by epidemiologists. In a new paper, COVID in the Nursing Homes: The US Experience, my co-author Markus Bjoerkheim and I ask whether focused protection could have worked.

Nursing homes were the epicenter of the pandemic. Even though only about 1.3 million people live in nursing homes at a point in time, the death toll in nursing homes accounted for almost 30 per cent of total Covid-19 deaths in the US during 2020. Thus we asked whether focusing protection on the nursing homes was possible. One way of evaluating focused protection is to see whether any type of nursing homes were better than others. In other words, what can we learn from best practices?

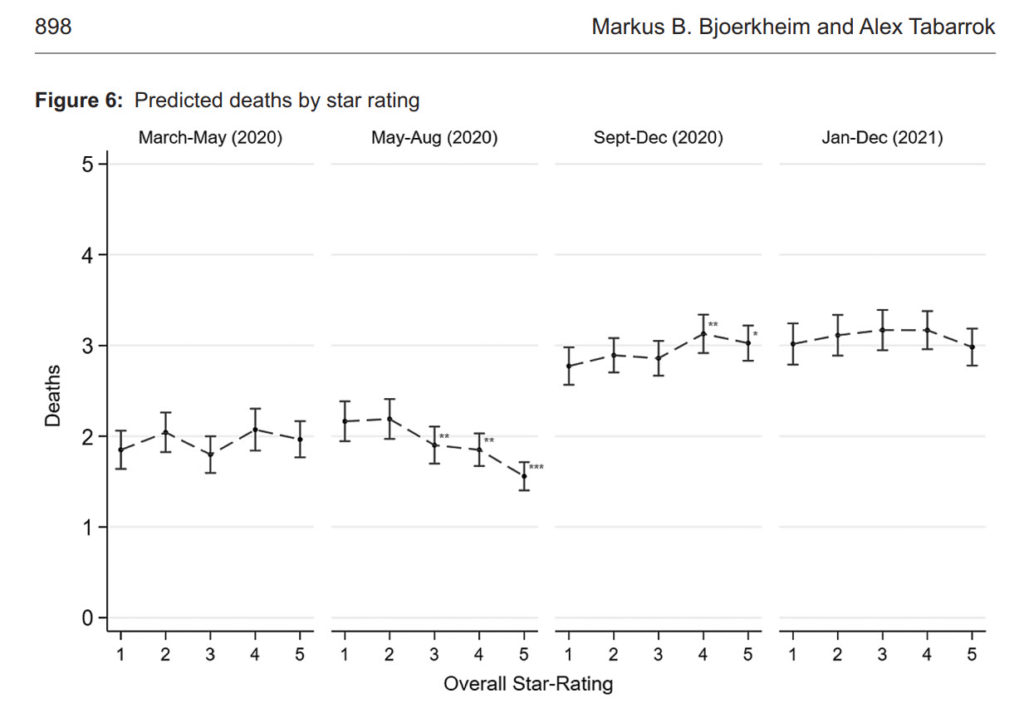

The Centers for Medicaire and Medicaid Services (CMS) has a Five-Star Rating system for nursing homes. The rating system is based on comprehensive data from annual health inspections, staff payrolls, and clinical quality measures from quarterly Minimum Data Set assessments. The rating system has been validated against other measures of quality, such as mortality and hospital readmissions. The ratings are pre-pandemic ratings. Thus, the question to ask is whether higher-quality homes had better Covid-19 outcomes? The answer? No.

The following figure shows predicted deaths by 5-star rating. There is no systematic relationship between nursing homes rating and COVID deaths. (In the figure, we control for factors outside of a nursing homes control, such as case prevalence in the local community. But even if you don’t control for other factors there is little to no relationship. See the paper for more.) Case prevalence in the community not nursing home quality determined death rates.

More generally, we do some exploratory data analysis to see whether there were any “islands of protection” in the sea of COVID and the answer is basically no. Some facilities did more rapid tests and that was good but surprisingly (to us) the numbers of rapid tests needed to scale nationally and make a substantial difference in nursing home deaths was far out of sample and below realistic levels.

Finally, keep in mind that the United States did focused protection. Visits to nursing homes were stopped and residents and staff were tested to a high degree. What the US did was focused protection and lockdowns and masking and we still we had a tremendous death toll in the nursing homes. Focused protection without community controls would have led to more deaths, both in the nursing homes and in the larger community. Whether that would have been a reasonable tradeoff is another question but there is no evidence that we could have lifted community controls and also better protected the nursing homes. Indeed, as I pointed out at the time, lifting community controls would have made it much more difficult to protect the nursing homes.

Testing Freedom

I did a podcast with Brink Lindsey of the Niskanen Center. Here’s one bit on the FDA’s long-history of banning home tests:

Brink Lindsey: …it’s on the rapid testing that we had inexplicable delays. Rapid tests, home tests were ubiquitous in Europe and Asia months before they were in the United States. What was going on?

Alex Tabarrok: So I think it’s not actually inexplicable because the FDA has a long, long history of just hating people testing themselves. So the FDA was against pregnancy tests, they didn’t like that, they said women they need to consult with a doctor, only the physician can do the test because literally women could become hysterical if they were pregnant or if they weren’t pregnant, this was a safety issue. There was no question that the test itself was safe or worked. Instead what the FDA said, “We can regulate this because the user using it, this could create safety issues because they could commit suicide or they could do something crazy.” So they totally expanded the meaning of safety from is the test safe to can somebody be trusted to use a pregnancy test?

Then we had exactly the same thing with AIDS testing. So we delayed personal at-home tests for AIDS for literally 25 years. 25 years these tests were unavailable because the FDA again said, “Well, they’re dangerous.” And why are they dangerous? “Well, we don’t know what people will do with this knowledge about their own bodies.” Now, of course, you can get an HIV test from Amazon and the world hasn’t collapsed. They did the same thing with genetic tests from companies like 23andMe. So I said, “Our bodies ourselves, our DNA ourselves.” That people have a right to know about the functioning of their own bodies. This to me is a very clear violation of the Constitutions on multiple respects. It just stuns me, it just stuns me that anybody could think that you don’t have a right to know, we’re going to prevent you from learning something about the operation of your own body.

Again, the issue here was never does the test work. In fact, the labs which produce these tests, those labs are regulated outside of the FDA. So whether the test actually works, whether yes, it identifies this gene, all issues of that nature, what is the sensitivity and the specificity, are the tests produced in a proper laboratory, I don’t have a lot of problem with that because that’s all something which the consumers themselves would want. What I do have a problem with is then the FDA saying, “No, you can’t have access to this test because we don’t know what you’re going to do about it, what you’re going to think about it.” And that to me is outrageous.

Here’s the full transcript and video.

The Rise and Decline and Rise Again of Mancur Olson

Mancur Olson’s The Rise and Decline of Nations is one of my favorite books and a classic of public choice. Olson may well have won the Nobel prize had he not died young. He summarized his book in nine implications of which I will present four:

Mancur Olson’s The Rise and Decline of Nations is one of my favorite books and a classic of public choice. Olson may well have won the Nobel prize had he not died young. He summarized his book in nine implications of which I will present four:

2. Stable societies with unchanged boundaries tend to accumulate more collusions and organizations for collective action over time. The longer the country is stable, the more distributional coalitions they’re going to have.

6. Distributional coalitions make decisions more slowly than the individuals and firms of which they are comprised, tend to have crowded agendas and bargaining tables, and more often fix prices than quantities. Since there is so much bargaining, lobbying, and other interactions that need to occur among groups, the process moves more slowly in reaching a conclusion. In collusive groups, prices are easier to fix than quantities because it is easier to monitor whether other industries are selling at a different price, while it may be difficult to monitor the actual quantities they are producing.

7. Distributional coalitions slow down a society’s capacity to adopt new technologies and to reallocate resources in response to changing conditions, and thereby reduce the rate of economic growth. Since it is difficult to make decisions, and since many groups have an interest in the status quo, it will be more difficult to adopt new technologies, create new industries, and generally adapt to changing environments.

9. The accumulation of distributional coalitions increases the complexity of regulation, the role of government, and the complexity of understandings, and changes the direction of social evolution. As the number of distributional coalitions grows, it will make policy-making increasingly difficult, and social evolution will focus more on distributing wealth among groups than on economic efficiency and growth.

Olson’s book has become less well known over the years but you can gauge it’s continued relevance from this excellent thread by Ezra Klein which gets at some of the consequences of the forces Olson explained:

A key failure of liberalism in this era is the inability to build in a way that inspires confidence in more building. Infrastructure comes in overbudget and late, if it comes in at all. There aren’t enough homes, enough rapid tests, even enough good government web sites. I’ve covered a lot of these processes, and it’s important to say: Most decisions along the way make individual sense, even if they lead to collective failure.

If the problem here was idiots and crooks, it’d be easy to solve. Sadly, it’s (usually) not. Take the parklets. There are fire safety concerns. SFMTA is losing revenue. Some pose disability access issues. It’s not crazy to try and take everyone’s concerns into account. But you end up with an outcome everyone kind of hates.

I’ve seen this happen again and again. Every time I look into it, I talk to well-meaning people able to give rational accounts of their decisions.

It usually comes down to risk. If you do X, Y might happen, and even if Y is unlikely, you really don’t want to be blamed for it. But what you see, eventually, is that our mechanisms of governance have become so risk averse that they are now running *tremendous* risks because of the problems they cannot, or will not, solve. And you can say: Who cares? It’s just parklets/HeathCare.gov/rapid tests/high-speed rail/housing/etc.

But it all adds up.

There’s both a political and a substantive problem here.

The political problem is if people keep watching the government fail to build things well, they won’t believe the government can build things well. So they won’t trust it to build. And they won’t even be wrong. The substantive problem, of course, is that we need government to build things, and solve big problems.

If it’s so hard to build parklets, how do you think think that multi-trillion dollar, breakneck investment in energy infrastructure is going to go?

This isn’t a problem that just afflicts liberal governance, of course.All these problems were present federally under Trump and Bush. They are present under Republican governors and mayors. But it’s a bigger problem for liberalism because liberalism has bigger public ambitions, and it requires trust in the government to succeed. I’m going to be working a lot over the next year on the idea of supply-side progressivism, and this is an important part.

ProPublica on FDA Delay

If you have been following MR for the last 18 months (or 18 years!) you won’t find much new in this ProPublica piece on FDA delay in approving rapid tests but, other than being late to the game, it’s a good piece. Two points are worth emphasizing. First, some of the problem has been simple bureaucratic delay and inefficiency.

![]()

In late May, WHPM head of international sales Chris Patterson said, the company got a confusing email from its FDA reviewer asking for information that had in fact already been provided. WHPM responded within two days. Months passed. In September, after a bit more back and forth, the FDA wrote to say it had identified other deficiencies, and wouldn’t review the rest of the application. Even if WHPM fixed the issues, the application would be “deprioritized,” or moved to the back of the line.

“We spent our own million dollars developing this thing, at their encouragement, and then they just treat you like a criminal,” said Patterson. Meanwhile, the WHPM rapid test has been approved in Mexico and the European Union, where the company has received large orders.

An FDA scientist who vetted COVID-19 test applications told ProPublica he became so frustrated by delays that he quit the agency earlier this year. “They’re neither denying the bad ones or approving the good ones,” he said, asking to remain anonymous because his current work requires dealing with the agency.

Recall my review of Joseph Gulfo’s Innovation Breakdown.

Second, the FDA has engaged in regulatory nationalism–refusing to look at trial data from patients in other countries. This is madness when India does it and madness when the US does it.

For example, the biopharmaceutical giant Roche told ProPublica that it submitted a home test in early 2021, but it was rejected by the FDA because the trials had been done partly in Europe. The test had compared favorably with Abbott’s rapid test, and received European Union approval in June. The company plans to resubmit an application by the end of the year.

A smaller company, which didn’t want to be named because it has other contracts with the U.S. government, withdrew its pre-application for a rapid antigen test with integrated smartphone-based reporting because it heard its trial data from India — collected as the delta variant was surging there — wouldn’t be accepted. Doing the trials in the U.S. would have cost millions.

Photo credit: MaxPixel.

The Promising Pathway Act

Operation Warp Speed showed that we can move much faster. FDA delay in approving rapid tests shows that we should move much faster. There is a window of opportunity for reform. The excellent Bart Madden and Siri Terjesen argue for the Promising Pathways Act.

One particularly exciting development is the Promising Pathway Act (PPA), recently introduced in Congress. PPA would reduce bureaucracy via legal changes and provide individuals with efficient early access to potential new drugs.

Under PPA, new drugs will receive provisional approval five to seven years earlier than the status quo via a two-year provisional approval. Drugs that demonstrate patient benefits could be renewed for a maximum of six years, and the FDA could grant full approval at any time based on real-world as opposed to clinical trial data documenting favorable treatments results.

The PPA allows patients, advised by their doctors, to choose early access to promising but not-yet-FDA -approved drugs. Patients and doctors would make informed decisions about using either approved or new medicines that demonstrate safety and initial effectiveness compared to approved drugs.

…Patients and doctors can log into an internet registry database for early access drugs that would contain treatment outcomes, side effects, genetic data, and biomarkers. Scientific researchers, as well as patients, will also benefit from the identification of subgroups of patients who do exceptionally well or fail to respond.

Data from the registry will open knowledge pathways to improve the biopharmaceutical industry’s research outlays to benefit future patients.

With radically lower regulatory costs plus heightened competition as more companies participate, expect substantially lower prescription drug prices for provisional approval drugs.

Here is the text of the PPA.

Why Doesn’t the United States Have Test Abundance?!

We have vaccine abundance in the United States but not test abundance. Germany has test abundance. Tests are easily available at the supermarket or the corner store and they are cheap, five tests for 3.75 euro or less than a dollar each. Billiger! In Great Britain you can get a 14 pack for free. The Canadians are also distributing packs of tests to small businesses for free to test their employees.

In the United States, the FDA has approved less than a handful of true at-home tests and, partially as a result, they are expensive at $10 to $20 per test, i.e. more than ten times as expensive as in Germany. Germany has approved over 50 of these tests including tests from American firms not approved in the United States. The rapid tests are excellent for identifying infectiousness and they are an important weapon, alongside vaccines, for controlling viral spread and making gatherings safe but you can’t expect people to use them more than a handful of times at $10 per use.

We ought to have testing abundance in the US and not lag behind Germany, the UK and Canada. As usual, I say if it’s good enough for the Germans it’s good enough for me.

Addendum: The excellent Michael Mina continues to bang the drum.

The TGA is Worse than the FDA, and the Australian Lockdown

I have been highly critical of the FDA but in Australia the FDA is almost a model to be emulated. Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden do not mince words:

At the end of 2020, as vaccines were rolling out en masse in the Northern Hemisphere, the TGA [Therapeutic Goods Administration, AT] flatly refused to issue the emergency authorisations other regulators did. As a result, the TGA didn’t approve the Pfizer vaccine until January 25, more than six weeks after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), itself not exactly the poster child of expeditiousness.

Similarly, the TGA didn’t approve the AstraZeneca vaccine until February 16, almost seven weeks after the UK.

In case you’re wondering “what difference does six weeks make?“, think again. Were our rollout six weeks faster, the current Sydney outbreak would likely never have exploded, saving many lives and livelihoods. In the face of an exponentially spreading virus that has become twice as infectious, six weeks is an eternity. And, indeed, nothing has changed. The TGA approved the Moderna vaccine this week, eight months after the FDA.

It approved looser cold storage requirements for the Pfizer vaccine, which would allow the vaccine to be more widely distributed and reduce wastage, on April 8, six weeks after the FDA. And it approved the Pfizer vaccine for use by 12 to 15-year-olds on July 23, more than 10 weeks after the FDA.

And then there’s the TGA’s staggering decision not to approve in-home rapid tests over reliability concerns despite their widespread approval and use overseas.

Where’s the approval of the mix-and-match vaccine regimen, used to great effect in Canada, where AstraZeneca is combined with Pfizer to expand supply and increase efficacy? Where’s the guidance for those who’ve received two doses of AstraZeneca that they’ll be able to receive a Pfizer booster later?

In the aftermath of the pandemic, when almost all of us should be fully vaccinated,there will be ample opportunity to figure out exactly who is to blame for what.

But the slow, insular, and excessively cautious advice of our medical regulatory complex, which comprehensively failed to grasp the massive consequences of delay and inaction, must be right at the top of that list.

You might be tempted to argued that the TGA can afford to take its time since COVID hasn’t been as bad in Australia as in the United States but that would be to ignore the costs of the Australian lockdown.

Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that

- Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

- Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Australia has now violated each and every clause of this universal human right and seemingly without much debate or objection. It is deeply troubling to see people prevented from leaving or entering their own country and soldiers in the street making sure people do not travel beyond a perimeter surrounding their homes. The costs of lockdown are very high and thus so is any delay in ending these unprecedented infringements on liberty.

Testing and the NFL

NYTimes: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health announced a new initiative on Wednesday to help determine whether frequent, widespread use of rapid coronavirus tests slows the spread of the virus.

The program will make rapid at-home antigen tests freely available to every resident of two communities, Pitt County, N.C., and Hamilton County, Tenn., enough for a total of 160,000 people to test themselves for the coronavirus three times a week for a month.

“This effort is precisely what I and others have been calling for nearly a year — widespread, accessible rapid tests to help curb transmission,” said Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at Harvard University who has been a vocal proponent of rapid, at-home testing programs.

I guess this is good news it just feels like something that in a different time line, happened long ago. Here is Derek Thompson in an excellent piece making exactly that point:

Imagine a parallel universe where Americans were tested massively, constantly, without care for cost, while those who tested negative continued more or less about their daily life.

In fact, that parallel universe exists. It’s the National Football League.

..After an October outbreak, the NFL moved to daily testing of all its players and instituted new restrictions on player behavior and stricter rules on ventilation and social distancing. The league also used electronic tracking bracelets to trace close contacts of people who tested positive. Throughout the season, the NFL spent about $100 million on more than 900,000 tests performed on more than 11,000 players and staff members. In January, the CDC published an analysis of the league that concluded, “Daily testing allowed early, albeit not immediate, identification of infection,” enabling the league to play the game safely.

You could write off the NFL’s season as the idiosyncratic achievement of a greedy sport with nearly unlimited resources. But I can think of another self-interested institution with nearly unlimited resources: It’s the government of a country with a $20 trillion economy and full control over its own currency. Unlike the NFL, though, the U.S. never made mass testing its institutional priority.

“The NFL was almost like a Korea within the United States,” Alex Tabarrok told me. “And it’s not just the NFL. Many universities have done a fabulous job, like Cornell. They have followed the Korea example, which is repeated testing of students combined with quick isolation in campus dorms. Mass testing is a policy that works in practice, and it works in theory. It’s crazy to me that we didn’t try it.” Tabarrok said we can’t be sure that a Korean or NFL-style approach to national testing would have guaranteed Korean or NFL-style outcomes. After all, that would have meant averting about 500,000 deaths. Rather, he said, comprehensive early testing was our best shot at reducing deaths and getting back to normal faster.

Most Popular MR Posts of the Year

Here is a selection of the most popular MR posts of 2020. COVID was a big of course. Let’s start with Tyler’s post warning that herd immunity was fragile because it holds only “for the current configuration of social relations”. Absolutely correct.

The fragility of herd immunity

Tyler also predicted the pandemic yo-yo and Tyler’s post (or was it Tyrone?) What does this economist think of epidemiologists? was popular.

Tyler has an amazing ability to be ahead of the curve. A case in point, What libertarianism has become and will become — State Capacity Libertarianism was written on January 1 of last year, before anyone was talking about pandemics! State capacity libertarianism became my leitmotif for the year. I worked with Kremer on pushing government to use market incentives to increase vaccine supply and at the same repeatedly demanded that the FDA move faster and stop prohibiting people from taking vaccines or using rapid tests. As I put it;

Fake libertarians whine about masks. Real libertarians assert the right to medical self-defense and demand access to vaccines on a right to try basis.

See my 2015 post Is the FDA Too Conservative or Too Aggressive for a good review of ideas on the FDA. A silver lining of the pandemic may be that more people realize that FDA delay kills.

My historical posts the The Forgotten Recession and Pandemic of 1957 and What Worked in 1918? and the frightening The Lasting Effects of the the 1918 Influenza Pandemic were well linked.

Outside of COVID, Tyler’s 2005 post Why did so many Germans support Hitler? suddenly attracted a lot of interest. I wonder why?

Policing was also popular including my post Why Are the Police in Charge of Road Safety? which called for unbundling the police and my post Underpoliced and Overprisoned revisited.

Tyler’s great post The economic policy of Elizabeth Warren remains more relevant than I would like. On a more positive note see Tyler’s post Best Non-Fiction Books of the Year.

One of the most popular posts of the year and my most popular post was The Gaslighting of Parasite.

But the post attracting the most page views in 2020 by far, however, was Tyler’s and it was…

You people are weird. Don’t expect more UFO content this year. Unless, well you know.

Our Antibodies, Our Selves

In 2013 I wrote, Our DNA, Our Selves, arguing against the FDA’s crackdown on genetic readouts from firms like 23andMe. The FDA, however, proved succesful in its crackdown and that is why rapid at-home antigen tests are not available today and why tens of thousands of people are dying from COVID unnecessarily. Regulations have unintended consequences.

Let’s recap:

Consider, I swab the inside of my cheek and send the sample to a firm. The idea that the FDA can rule on what the firm can and cannot tell me about my own genes is absurd–it’s no different than the FDA trying to regulate what my doctor can tell me after a physical examination or what my optometrist can tell me after an eye examination (Please read the first line. “G T A C C A…”).

The idea that the FDA can regulate and control what individuals may learn about their own bodies is deeply offensive and, in my view, plainly unconstitutional.

Let me be clear, I am not offended by all regulation of genetic tests. Indeed, genetic tests are already regulated. To be precise, the labs that perform genetic tests are regulated by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) as overseen by the CMS (here is an excellent primer). The CLIA requires all labs, including the labs used by 23andMe, to be inspected for quality control, record keeping and the qualifications of their personnel. The goal is to ensure that the tests are accurate, reliable, timely, confidential and not risky to patients. I am not offended when the goal of regulation is to help consumers buy the product that they have contracted to buy.

What the FDA wants to do is categorically different. The FDA wants to regulate genetic tests as a high-risk medical device that cannot be sold until and unless the FDA permits it be sold.

Moreover, the FDA wants to judge not the analytic validity of the tests, whether the tests accurately read the genetic code as the firms promise (already regulated under the CLIA) but the clinical validity, whether particular identified alleles are causal for conditions or disease. The latter requirement is the death-knell for the products because of the expense and time it takes to prove specific genes are causal for diseases. Moreover, it means that firms like 23andMe will not be able to tell consumers about their own DNA but instead will only be allowed to offer a peek at the sections of code that the FDA has deemed it ok for consumers to see.

Ten years later we now need rapid antigen tests but the issue, as Michael Mina points out in an excellent interview with Malcolm Gladwell, is that we have medicalized all tests and readouts. Instead of thinking about the individual as having a right to know about their own body, we treated every test or readout as if the only user were a physician. Thus, instead of thinking about the value of these tests for individuals and for public health, the FDA failed to approve rapid antigen tests because it regarded them as inferior to PCR tests, for a physician diagnosing disease.

Here’s Mina (roughly transcribed and lightly edited)

The only pathway that we have to evaluate tests like this are medical diagnostic pathways, pathways designed specifically to ensure that a physician like a detective is getting all the information they need to diagnose a sick person… We have so devalued and defunded public health…that we don’t have a regulatory pathway to approve a test whose primary objective is stopping an epidemic versus diagnosing a sick person. And that has held everything up. All the companies that could be producing these rapid tests in the millions and millions, they have been sitting on these tests trying to hone them so they can pass FDA standards as a medical diagnostic.

It’s not just slowing down their approval it’s actually bottle necking the companies into creating tests that are not going to be as scalable as they are having to use more expensive reagents and packing the tests with instruments so they can pass FDA review when in reality they are just these little pieces of papers. If we can do the cheap version they can be made very fast but the just won’t get through the FDA.

Gladwell: I find your explanation unconvincing. How dumb is the FDA?…If you make the exact argument you made to me…the FDA is not going to see your logic?

It’s not that they are not smart it’s that this is a regulatory body, they just don’t have a pathway. You can’t apply for approval for a public health test tool…In our country the medical establishment is extremely strong, you can’t go to get a cholesterol test without getting a prescription from your doctor. Why can’t we know that? It’s all through this very heavy medical lens and changing that, getting that big ship to turn is turning out to be a very, very difficult task but leading to potentially tens or hundreds or thousands of deaths that don’t need to be happening.

Infected versus Infectious

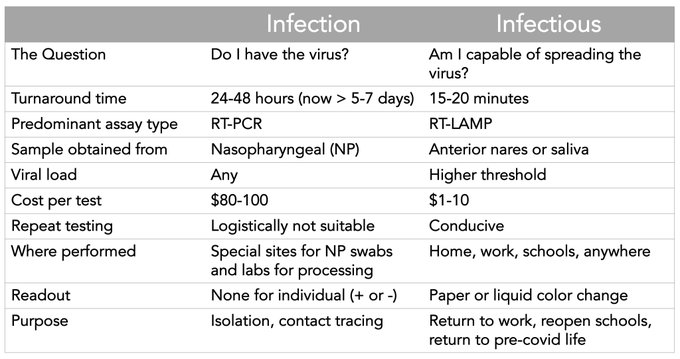

As I said in my post Frequent, Fast, and Cheap is Better than Sensitive we shouldn’t be comparing virus tests head-to-head, as if all tests serve the same purpose. Instead, we should recognize that tests have comparative advantages and a cheap, fast, frequent testing regime can be better in some respects than a slow, infrequent but more sensitive testing regime. Both regimes can be useful when used appropriately and especially when they are used in combination.

Eric Topol has a good graphic.

As Topol also notes:

In order to get this done, we need a reboot at @US_FDA, which currently requires rapid tests to perform like PCR tests. That’s wrong. This is a new diagnostic category for the *infectious* endpoint, requiring new standards and prospective validation.

The FDA has sort-of indicated that they might be open to this.

Much, much too slow, of course. Matching a virus that grows exponentially against a risk-averse, overly-cautious FDA has been a recipe for disaster.

Why I don’t like Fischer Random 960

As you may know, a major tournament is going on right now, based on a variant of Fischer Random rules, sometimes misleadingly called “Freestyle.” Subject to some constraints, the pieces are placed into the starting position randomly, so in Fischer Random chess opening preparation is useless. You have to start thinking from move one. This is a big advantage in a game where often the entire contest is absorbed into 20-30 moves of advance opening preparation, with little or no real sporting element appearing over the board.

Yet I don’t like Fischer Random, for a few hard to fix reasons:

1. Most of the time, at least prior to the endgame, I don’t understand what is going on. Even with computer assistance. I could put in five to ten minutes to study the position, and get a sense of the constraints, but as a spectator I don’t want to do that. As a relatively high opportunity cost person, I am not going to do that.

1b. Classical chess sometimes generates positions where one does not really understand what is going on. Then it is thrilling, precisely because it is occasional. A perpetual “fog of war,” as we receive in Fischer Random, just isn’t that thrilling. In the opening, for instance, I don’t even know if one player is attempting “a risky strategy.” I am not sure the player knows either. And I don’t feel that watching more Fischer Random would change that, as there are hundreds of different possible opening positions, mostly with different properties.

2. The younger players have a notable advantage, because they are better at calculating concrete variations and rely less on intuition. (We already see this in the current results.) Experience is simply worth much less in this very novel format. For any one tournament, that is an interesting intrigue. But over time it is a bore, as if only rookies and sophomores could win NBA titles. In fact what spectators enjoy watching is Steph Curry going up against Lebron James, or the analogs in chess. We want to see Magnus meet Fabiano again, not watch two eighteen-year-olds slug it out. Sorry, Pragga! You’ll have your day in the sun.

3. Fischer Random cuts off chess from the rest of its history. That is otherwise a big advantage of chess over many other games and contests. I like seeing that a player’s move is connected to say an idea from Tal in the early 1960s, or whatever. I like “Oh, the Giuoco Piano is making a comeback at top levels,” or “today’s players are more willing to sacrifice the exchange than in the 1970s,” and so on.

4. I get frustrated seeing all those Kings sitting on F1, not able to castle in the traditional sense. There are rules for castling in Fischer Random, but it feels more like pressing the “hyperspace” button in the old Space Invaders video game than anything else. Who wants to see a Knight on C1 for twenty-five moves? Not I.

5. I agree that current opening prep is insanely out of control. I am fine with the remedy of 25-minutes per player Rapid games, or anything in that range, with increment of course. Those contests are consistently exciting and they are not forced draws (you can play something weird against the Petroff, or to begin with) nor are they dominated by prep.

6. If you don’t want to watch Rapid, I would rather randomize the first few opening moves than the placement of the pieces. If you don’t control the first three (seven? ten?) first moves, once again opening prep becomes much tougher. So what if some games start with 1. b4 b6? The resulting position is still playable for both sides and furthermore it still makes intuitive sense to chess spectators. Of course the computers would restrict this randomization to sequences that still are playable for both sides. The very exact nature of current chess opening prep in fact implies you need only a very small change in the rules to disrupt it, not the kind of huge change represented by Fischer Random.

That all said, I am all for experimentation, it’s just that some of them should be strangled in the crib.

The resurgence of crypto

Crypto and bitcoin, among their other uses, are Rorschach tests for commentators. As these institutions evolve, are you capable of changing your mind and updating in response to new data? Sadly, many people are failing that test and instead staking out inflexible ideological ground.

Bitcoin prices are now in the range of $44,000, and the asset has more than doubled in value this year. Perhaps more surprisingly yet, NFT markets are making a comeback. Many of the older NFT purchases remain nearly worthless, but interest in the asset class as a whole has perked up.

These developments should induce us to reevaluate crypto in a positive direction. If in the past you have argued that crypto is a bubble, can it be the bubble is back yet again? Typically bubbles, once they burst, do not return in a few years’ time. You still will find Beanie Babies on eBay, but they are not surrounded by any degree of excitement. Similarly, the prices of Dutch tulip bulbs appear normal and well-behaved, as that bubble faded out long ago. Bitcoin, in contrast, has attracted investor interest anew time and again.

It is time to realize that crypto is more like a lottery ticket than a bubble or a fraud, and it is a lottery ticket with a good chance of paying off. It is a bet on whether it will prove possible to build out crypto infrastructure as a long-term project, integrated with mainstream finance. If that project can succeed, crypto will be worth a lot, probably considerably more than its current price. If not, crypto assets will remain as a means for escaping capital controls and moving money across borders, or perhaps to skirt the law with illegal purchases.

What might such an infrastructure look like? To make just a few guesses, your crypto wallet might be integrated with your Visa and other credit cards (perhaps using AI?). Fidelity, Vanguard, large banks and other mainstream financial institutions will allow you to hold and trade crypto, just as you might now have a money market fund. Crypto-based lending could help you invest in high-return, high-risk overseas opportunities with some subset of your portfolio. Stablecoins will circulate as a form of “programmable money,” and they will circulate on a regular and normal basis; such a plan was just initiated by the French bank SocGen. On a more exotic plane, AI-based agents, denied standard checking accounts, might use crypto to trade with each other.

I’m not arguing such scenarios are either good or bad, simply that the market sees some chance of them happening. And they are far more than “crypto is a fraud or a bubble.”

Whether that infrastructure will meet market and regulatory tests is difficult to forecast. It has never happened before, and thus no one can claim to be a true expert on the matter. Thus your opinion of crypto should be changing each and every day, as you observe fluctuations in market prices and other changes in the objective conditions.

In this perspective, there are some pretty clear reasons why the price of bitcoin is higher again. First, real interest rates have been falling, and fairly rapidly. Ten-year rates are now closer to four per cent than to five per cent. Since crypto financial infrastructure is a long-term project that won’t be completed in a year or two, lower real interest rates raise the value of that project considerably. The value of bitcoin rises as well, just as many other long-term assets rise in value with lower real interest rates. And if interest rates continue to fall, crypto prices could easily continue to rise.

The resurgence of crypto likely has other causes. The story of SBF is receding from the headlines with the end of his trial. That makes crypto look less scammy. On the regulatory side the United States did not try to shut down Binance, in spite of alleged scandals at the exchange. That is the regulators signaling they are not going to try to destroy crypto. Soon the SEC may approve spot bitcoin ETFs, which would make it easier and safer to invest in that asset. Nor have state laws popped up that might be trying to shut down crypto markets. Finally, the election of Donald Trump as President has not faded as a possibility, and in the past Trump has been supportive of crypto. Overall, the tea leaves are signaling that the U.S. government is making its peace with crypto, or at least with some parts of the market.

So with crypto the most important thing is to keep an open mind. As of late, events have been doing much to signal open and growing possibilities, rather than a world where crypto is shut down.