Results for “statistical discrimination” 30 found

Ban the Box or Require the Box?

Ban the box policies forbid employers from asking about a criminal record on a job application. Ban the box policies don’t forbid employers from running criminal background checks they only forbid employers from asking about criminal history at the application/interview stage. The policies are supposed to give people with a criminal background a better shot at a job. Since blacks are more likely to have a criminal history than whites, the policies are supposed to especially increase black employment.

One potential problem with these laws is that employers may adjust their behavior in response. In particular, since blacks are more likely than whites to have a criminal history, a simple, even if imperfect, substitute for not interviewing people who have a criminal history is to not interview blacks. Employers can’t ask about race on a job application but black and white names are distinctive enough so that based on name alone, one can guess with a high probability of being correct whether an applicant is black or white. In an important and impressive new paper, Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr examine how employers respond to ban the box.

Agan and Starr sent out approximately 15,000 fake job applications to employers in New York and New Jersey. Otherwise identical applications were randomized across distinctively black and white (male) names. Half the applications were sent just before and another half sent just after ban the box policies took effect. Not all firms used the box even when legal so Agan and Starr use a powerful triple-difference strategy to estimate causal effects (the black-white difference in callback rates between stores that did and did not use the box before and after the law).

Agan and Starr sent out approximately 15,000 fake job applications to employers in New York and New Jersey. Otherwise identical applications were randomized across distinctively black and white (male) names. Half the applications were sent just before and another half sent just after ban the box policies took effect. Not all firms used the box even when legal so Agan and Starr use a powerful triple-difference strategy to estimate causal effects (the black-white difference in callback rates between stores that did and did not use the box before and after the law).

Agan and Starr find that banning the box significantly increases racial discrimination in callbacks.

One can see the basic story in the situation before ban the box went into effect. Employers who asked about criminal history used that information to eliminate some applicants and this necessarily affected blacks more since they are more likely to have a criminal history. But once the applicants with a criminal history were removed, “box” employers called back blacks and whites for interviews at equal rates. In other words, the box leveled the playing field for applicants without a criminal history.

Employers who didn’t use the box did something simpler but more nefarious–they offered blacks fewer callbacks compared to otherwise identical whites, regardless of criminal history. Together the results suggest that employers use distinctively black names to statistically discriminate.

When the box is banned it’s no longer possible to cheaply level the playing field so more employers begin to statistically discriminate by offering fewer callbacks to blacks. As a result, banning the box may benefit black men with criminal records but it comes at the expense of black men without records who, when the box is banned, no longer have an easy way of signaling that they don’t have a criminal record. Sadly, a policy that was intended to raise the employment prospects of black men ends up having the biggest positive effect on white men with a criminal record.

Agan and Starr suggest one possible innovation–blind employers to names. I think that is the wrong lesson to draw. Agan and Starr look at callbacks but what we really care about is jobs. You can blind employers to names in initial applications but employers learn about race eventually. Moreover, there are many other margins for employers to adjust. Employers, for example, could simply start increasing the number of employees they put through (post-interview) criminal background checks.

Policies like ban the box try to get people to do the “right thing” by blinding people to certain types of information. But blinded people tend to use other cues to achieve their interests and when those other cues are less informative that often makes things worse.

Rather than ban the box a plausibly better policy would be to require the box. Requiring all employers to ask about criminal history would tend to hurt anyone with a criminal record but it could also level racial differences among those without a criminal record. One can, of course, argue either side of that tradeoff and that is my point.

More generally, instead of blinding employers a better idea is to change real constraints. At the same time as governments are forcing employers to ban the box, for example, they are passing occupational licensing laws which often forbid employers from hiring workers with criminal records. Banning the box and simultaneously forbidding employers from hiring workers with criminal records illustrates the incoherence of public policy in an interest-group driven system.

Ban the box is another example of good intentions gone awry because the man of system tries to arrange people as if they were pieces on a chessboard, without understanding that:

…in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder. (Adam Smith, ToMS)

Addendum 1: The Agan and Starr paper has much more of interest. Agan and Starr, find, for example, evidence of discrimination going beyond that associated with statistical discrimination and crime. In particular, whites are more likely to be hired in white neighborhoods and blacks are more likely to be hired in black neighborhoods.

Addendum 2: Agan was my former student at GMU. Her undergraduate paper (!), Sex Offender Registries: Fear without Function?, was published in the Journal of Law and Economics.

Totally conventional views I hold about Hillary Clinton

I’ve been receiving numerous requests for more of my “totally conventional views,” and someone asked me about HRC. We’ve never covered her in the past, so why not? But by construction of this series, none of what follows is at all new and probably there won’t be any discussion in the comments. But with that in mind, I’ll offer up these points:

1. Women are judged far more by their looks than are men, and Hillary’s are not right for the presidency. She doesn’t seem composed enough, schoolmarmish enough a’ la Thatcher, and frankly many men, when they see her in their mind’s eye, imagine a voice saying “Look here, buster…!” Her hair is not properly ordered for the Executive Office, and I suspect many Americans want for their first female President to appear somewhat ageless. I am not suggesting any of this is fair or even an efficient form of Bayesian statistical discrimination, but it is a reality.

2. If not for factor #1, a healthy Hillary would be a shoo-in for demographic reasons, but as it stands her chances of winning are overrated.

3. A Clinton Presidency is the most likely of any, from the major candidates, to serve up significant and enduring market-oriented reforms. She could bring along enough Democrats to work with the Republicans, and reclaim a version of the old Clinton legacy. That said, her presidency also is more likely to effect change in the opposite direction as well, so the net expected value here is hard to calculate and still may be negative.

4. Given #1 and #2, and other gender-related factors, your opinion about Hillary, no matter what it may be, is less reliable than you think. That suggests you should think about her less rather than more (sorry people for this post, what did Wittgenstein say about that ladder?), because I don’t think you’re going to see much of a payoff from grabbing here at that third derivative.

5. The willingness of the Clinton Foundation to solicit donations from foreign governments and leaders is corrupt, and yet mostly receives a free pass, in spite of some recent coverage on corporate donations. I read recently they might stop soliciting donations “…if Hillary runs for President,” also known as “hurry up and give now!” Arguably we would be electing a political machine as President of the United States, even more than usual.

6. Democratic intellectuals and operatives are quite unexcited — or should I say “fervently and passionately unexcited” — about the prospect of a Hillary candidacy. The energy is already drained from the room, and they haven’t opened the door yet.

7. There is still the question of how the press, and the American people, might process any subsequent revelations about Bill’s “activities” since leaving the White House.

8. It will be hard to avoid giving the public “Hillary fatigue,” given how many years she has been in the public eye. This is another reason why I think her chances are overrated, plus she will have to be very careful to carry herself in the debates just the right way, see #1 and #2 again.

9. It is easier to transcend race than gender.

Multiple equilibria?

That’s what I think of when I see that picture.

Trust was broken, most of all in the financial system, but like a wet spill this has soaked into many parts of the economy and polity.

Labor hiring is an investment, and we must move to higher levels of investment for the labor market to recover. For the most part, that is no longer a problem of nominal stickiness, as the quality of jobs has been varying for years, along with some wage adjustments. The nominal wage stickiness fairy was dominant in 2009 but is today just another spirit.

Employers are reluctant to hire stale labor, at any real wage, because they fear the associated morale problems. (Or at the requisite real wage, disability pay or idleness is a more attractive option for the worker.) This is partly fear, partly rational statistical discrimination. Employers will hire stale labor only when an extreme boom requires them to. Such an extreme boom must be seen as grounded in perceived increases in real wealth and justified increases in trust. That probably won’t come anytime soon, but we are inching our way back to it and someday it will come again. Solving the stale labor problem requires a very different path of recovery than solving the nominal wage stickiness problem.

In one very real sense, the economy is well below potential output (though less than many people think, due to the great stagnation). In another very real sense, that gap cannot be exploited in the short run by reflationary policy. Once again, it requires a reestablishment of trust. Trust is more easily broken than repaired.

In one very real sense, there is a significant demand shortfall. Yet repairing that demand shortfall requires many building blocks. Nominal reflation (which I favor) is only one of those building blocks. The others are rooted in trust and perceived real wealth, which are both slower to repair and require different policy instruments, plus the mere passage of time.

Under the multiple equilibria view, it is possible for employment and the real wage to recover together, albeit slowly. Under the nominal stickiness view, median real wages still need to take yet a further whack; oddly it is the Keynesians who are committed to the most extreme form of a TGS thesis.

It is time to integrate macroeconomics with institutional economics.

Arnold Kling on the political spectrum

Here in the United States, one thing that strikes me about my most liberal friends is how conservative their thinking is at a personal level. For their own children, and in talking about specific other people [TC: especially in the blogosphere!], they passionately stress individual responsibility. It is only when discussing public policy that they favor collectivism. The tension between their personal views and their political opinions is fascinating to observe. I would not be surprised to find that my friends' attachment to liberal politics is tenuous, and that some major event could cause a rapid, widespread shift toward a more conservative position.

Here is more. I would make the related point that, in the economics profession, academic liberals are especially likely to believe in statistical discrimination: "Does he have a Ph.d. from Harvard or MIT?" On the right, Chicago's previous reputation as an outsider school blunts this tendency, plus there have been Arizona, VPI, and other off-beat centers of market-oriented thought.

Credit Scores, Criminal Background Checks and Hiding the Bad Apples

A number of people (Slacktivist, Kevin Drum, Matt Yglesias, Megan Mcardle) are debating the use of credit scores in employment. Credit scores are useful at predicting all kinds of things including, for example, car accidents so there is good reason to believe that they are useful in employment. The above commentators tend to focus on the potential for scores to hurt the poor but that is not obvious. Consider a similar issue: Should employers be allowed to use background criminal checks when hiring?

One argument against is that black men are more likely to have criminal backgrounds and thus these criminal background checks discriminate against black men. Let's put aside the normative issues. What’s surprising is that under plausible circumstances criminal background checks can lead to an increase in the employment of black men. The reason is that without the background check employers face a risk that their employees are ex-cons. If employers are very averse to hiring ex-cons then they will seek to reduce this risk and one way of doing so is by not hiring any black men. As a result, a background check allows non ex-cons to distinguish themselves from the pack and to be hired. Furthermore, when background checks exist, non ex-cons know that they will not face statistical discrimination and thus have an increased incentive to invest in skills.

Consistent with this reasoning, although not demonstrative of the net effect, Holzer, Raphael and Stoll find that:

…employers who check criminal backgrounds are more likely to hire

African American workers, especially men. This effect is stronger among

those employers who report an aversion to hiring those with criminal

records than among those who do not.

My view is actually that criminals face too many post-crime impediments to reintegrating themselves within the workforce. Private incentives not to take a risk on an ex-con do not cohere with social incentives to reintegrate workers into society and thus we get too little hiring of ex-cons. As a result, ex-cons face a low opportunity cost of recidivism.

Nevertheless, banning criminal background checks or credit scores is probably not the best way to combat these types of problem. Banning criminal background checks increases the incentive to rely on less accurate statistical discrimination which discriminates against the innocent and reduces the incentive to invest in skills. In short, hiding the bad apples among the good comes at the expense of the good.

Edmund Phelps — Today’s Nobel Prize in economics

Edmund Phelps. Here is the announcement from Sweden.

Here is his autobiography. He was born in Chicago in 1933 and now teaches at Columbia. Here is his CV, and here is another version. Here are recent papers. His Wikipedia entry is a short stub, but watch it grow.

Here is his summary of his research. Here is another good summary of his work. This summary, from Sweden, is the best and most comprehensive, albeit more technical.

His main contribution is a better understanding of the Phillips curve and the dynamics of short-run unemployment and the concept of the natural rate of unemployment. He gave the Phillips curve microfoundations and developed the "expectations-augmented Phillips curve." As the name suggests, the level of inflationary expectations matter for how money will influence output.

Here is his memoir on developing the idea of the natural rate of unemployment. His most influential 1960s work suggested that economies possess a natural rate of unemployment, monetary policy can reduce unemployment only temporarily (NB: in his view this is a conclusion, and should not be an axiom in economic models), monetary policy can reduce unemployment temporarily, and Keynesian economics should not treat the rate of unemployment as arbitrarily at the whim of monetary and fiscal policy. He was also concerned with how the natural rate of employment can change over time; here is his 1997 paper on that topic.

The evolution of Phelps’s thought on how money can matter is complex. His later work stresses monetary non-neutrality, mostly through non-rational expectations and non-synchronized wage and price setting. His work in the 1980s focused on what the concept of rational expectations means in such complex environments.

Do not assume that early Phelps and late Phelps are saying the same things or arguing against the same opponents. Sometimes it is argued that he redefined macroeconomics twice. After criticizing Keynesianism, he later turned against the "rational expectations" point of view. He is a complex thinker, although it can be hard to divine his "bottom line." He fails to fit inside the "macroeconomics boxes" that have developed since the early 1980s, namely real business cycle theory vs. neo-Keynesianism.

Phelps’s work was considered revolutionary in the 1960s, though the subsequent work and influence of Milton Friedman have brought related ideas into the mainstream some time ago.

He also has done work on economic justice and how a Rawlsian maximin analysis might modify the idea of a zero rate of marginal taxation on top earners, as had been suggested by James Mirrlees. Phelps believes that considerations of justice and distribution are important, and neglected, in economic thinking. Once he had a piece in the Journal of Philosophy on ideas of justice in public finance.

He also wrote some well-known papers on what intergenerational justice means, the optimal accumulation of capital, and whether those allocations will prove sustainable and consistent over time. He asks what kind of principles should govern how much capital we should leave for the next generation. His 1961 work on capital theory formulated the notion of a "golden rule" of capital accumulation. It asked what savings rate would maximize per capita income on an ongoing basis. The concepts behind this work remain important for work on capital accumulation and also the sustainability of natural resource use and environmental policy. Phelps also generated the counterintuitive result that the savings rate can be too high, and that all generations could be better off with a lower savings rate. He does not, however, seem to think that this latter idea is policy-relevant. The best summary of this work on capital theory is here, scroll through a bit.

Lately he has been working on the possibility of subsidies for hiring low-wage labor and Eastern European transitions. Here is his book on wage subsidies. Here is a more popular Phelps piece on wage subsidies. He has also done work on the structural dynamics of economies and the underlying factors behind economic innovation. Here is an early Phelps paper on technological diffusion; surprisingly it is his most frequently cited work according to scholar.google.com. He looked to education and population size as key factors driving the rate of economic growth; this piece is a precursor of later work on endogenous growth theory.

Phelps also wrote a 1972 paper on statistical discrimination, one of the earliest formal economic treatments of that topic.

Here is Phelps on Project Syndicate, the link offers numerous essays on current events. The European malaise stems from lack of dynamism. He opposed the Bush tax cuts. Here is Phelps on the rise of the West and the need for humane capitalism. He has a broadly classical liberal slant but has adopted the modern liberal idea that distribution requires government intervention into labor markets and other parts of a modern economy. He has a strong concern with the moral foundations of a free society.

Here are his cites on scholar.google.com. 4600 is a relatively low number for a Nobel Laureate. Vernon Smith for instance has over 40,000. In part this relatively small number reflects the older nature of Phelps’s major contributions, and that often his ideas have been absorbed but without citation. Furthermore Phelps does not always write within the context of the most contemporary debates.

Over the last twenty years Phelps has spent a great deal of time in Europe. In general his European influence and reputation is stronger than in the United States.

My take: It is hard to argue with this pick. It is a good selection. His 1960s macro work was true, important, and extremely influential. The capital theory work endures and provides a foundation for subsequent theory. The overall scope is impressive, and Phelps’s concerns never strayed far from the real world.

But Phelps is not an economist who has influenced my own thinking much if at all. His major contributions were absorbed, and were standard fare, by the time I was a young’un. For instance I drunk the same macro milk through the writings of Milton Friedman. I find him to be a murky writer, and often he is frustrating to read and hard to pin down. His advocates would characterize him as a "rich" thinker.

What this Prize means: The big questions still matter. Unemployment, economic growth, labor markets, capital accumulation, fairness, discrimination, and justice across the generations are indeed worthy of economic attention. Phelps contributed to all of those areas. Normative questions matter. Relevance and breadth triumph over narrow technical skill.

Addendum: The U.S. has now won six Nobel Prizes in a row, but I bet we don’t get the Peace Prize this year.

Gender Debate

The Edge hosted a debate between Harvard psychologists Steven Pinker and Elizabeth Spelke on The Science of Gender and Science. It’s an excellent debate with both sides presenting good arguments. Be sure not to miss the concluding section – Pinker’s discussion of the Arrovian statistical discrimination/self-fulfilling prophecy argument is brilliant.

Econ Journal Watch — new issue

In this issue:Hospitals, communication, and dispute resolution: Florence R. LeCraw, Daniel Montanera, and Thomas A. Mroz criticize the statistical methods of a 2018 article in Health Affairs, and tell of their effort to get their criticisms into Health Affairs.Health Insurance Mandates and the Marriage of Young Adults: Aaron Gamino comments on the statistical modeling in a 2022 Journal of Human Resources article, whose authors Scott Barkowski and Joanne Song McLaughlin reply.Origins of the Opioid Crisis Reexamined: A 2022 article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics on the origins of the opioid crisis assigns considerable explanatory weight to the introduction and promotion of OxyContin. Robert Kaestner looks at the empirics behind the conclusion and suggests that it is without much foundation.Temperature and Economic Growth: As he did in the previous issue of this journal, David Barker investigates a piece of Federal Reserve research purporting to show that high temperatures decrease the rate of economic growth. Barker looks under the hood, replicates, and reports.Classical Liberalism in Romania, Past and Present: Radu Nechita and Vlad Tarko narrate the classical liberal movements in Romania, from the beginning of the 19th century, through the awful times of the 20th century, and down to today. The article extends the series on Classical Liberalism in Econ, by Country.Edward Westermarck’s Lectures on Adam Smith, delivered in 1914 at the University of Helsinki. Westermarck, of Finland, was an influential sociologist, anthropologist, and philosopher. His lectures are remarkably attentive toward Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments. The lectures are translated and introduced by Otto Pipatti.French economic liberalism versus occupational privilege: In 1753, Vincent Gournay wrote a memorial blasting the exclusionary privileges conferred upon guilds. The Chamber of Commerce of Lyon replied, and Gournay then responded with another memorial. The three-part exchange is translated here for the first time, and introduced by Benoît Malbranque.Professor McCloskey’s 1988 Letter Responding to a Letter from the President of Penn State: In 1988, Donald (now Deirdre) McCloskey received a letter about a passage in The Applied Theory of Price in an exercise on discrimination in labor markets. The letter and McCloskey’s response are reproduced here.EJW Audio:

- Sheilagh Ogilvie on 900 Years of European Guilds

- Art Carden on William H. Hutt

- David Barker on Temperature and Economic Growth

EJW books from CL Press:

Gender Differences in Peer Recognition by Economists

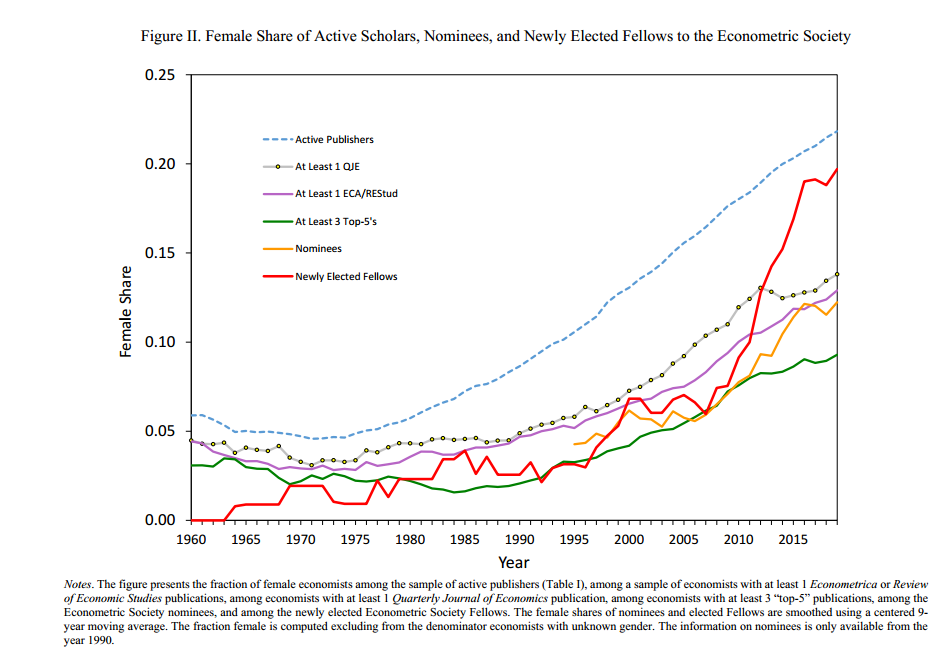

Card et al. study the selection of fellows to the prestigious Econometrics Society showing essentially that prior to about 1980 there was modest discrimination against women. Between 1980 and 2005 about equal access but since 2005 a large bias towards women. Not surprising but citation metrics give us a way of comparing selection with achievement.

The key result can be seen in the raw data–compare the green line of at least 3 top-5s with the red line of selection as an ES fellow.

Here is the abstract to the paper with more details.

We study the selection of Fellows of the Econometric Society, using a new data set of publications and citations for over 40,000 actively publishing economists since the early 1900s. Conditional on achievement, we document a large negative gap in the probability that women were selected as Fellows in the 1933-1979 period. This gap became positive (though not statistically significant) from 1980 to 2010, and in the past decade has become large and highly significant, with over a 100% increase in the probability of selection for female authors relative to males with similar publications and citations. The positive boost affects highly qualified female candidates (in the top 10% of authors) with no effect for the bottom 90%. Using nomination data for the past 30 years, we find a key proximate role for the Society’s Nominating Committee in this shift. Since 2012 the Committee has had an explicit mandate to nominate highly qualified women, and its nominees enjoy above-average election success (controlling for achievement). Looking beyond gender, we document similar shifts in the premium for geographic diversity: in the mid-2000s, both the Fellows and the Nominating Committee became significantly more likely to nominate and elect candidates from outside the US. Finally, we examine gender gaps in several other major awards for US economists. We show that the gaps in the probability of selection of new fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences closely parallel those of the Econometric Society, with historically negative penalties for women turning to positive premiums in recent years.

Was the New Deal Racist?

In recent decades, “racial disparity” has become the central framework for discussing inequities affecting African Americans in the United States. In this usage, disparity refers to the disproportionate statistical representation of some categorically defined populations on average in the distribution of undesirable things—unemployment, low wages, infant mortality, poor education, incarceration, etc. And by corollary logic, such social groupings are also found to be statistically underrepresented in desirable things—wealth, income, educational attainment, etc.

…Identifying disparate treatment or outcomes that correlate with racial difference can be a critical step in validating a complaint. However, the inclination to fixate on such disparities as the only objectionable form of inequality can create perverse political incentives. We devote a great deal of rhetorical and analytic energy to the project of determining just which groups, or population categories, suffer or have suffered the worst. Cynics have sometimes referred to this brand of what we might term political one-downsmanship as the “oppression Olympics”—a contest in which groups that have attained or are vying for legal protection effectively compete for the moral or cultural authority that comes with the designation of most victimized.

Even short of that cynical view, a central focus on group-level disparities can lead to mistaken diagnoses of the sources and character of the manifest inequalities it identifies.

Good art by women is cheaper

A rose painted by another name would cost more. In a new paper*, four academics show that art made by women sells for lower prices at auction than men’s, and suggest that this discount has nothing to do with talent or thematic choices. It is solely because the artists are female.

The authors used a sample of 1.9m transactions in art auctions across 49 countries in the period from 1970 to 2016. They found that art made by women sold at an average discount of 42% compared with works by men. However, auction prices can be distorted by a few famous artists whose output is perceived as extremely valuable. If transactions above $1m are excluded, then the discount falls to 19%.

…the researchers used a computer programme to generate paintings and randomly assign the results to artists with male or female names. They then asked participants to rate the paintings and ascribe a value. The experiment found that affluent individuals (those most likely to bid at auctions) attributed a lower value to works which the programme assigned to a woman. Clearly, this gap was unrelated to the artistic merit of the picture.

I don’t quite think that shows (non-statistical) discrimination, perhaps more convincing is this:

The average discount applied to the work of a given female artist was lowest in countries where women were more equal. (There are some exceptions to the rule, such as Brazil, where women’s art was highly rated.)

The good news is that the female discount has fallen over time. For transactions under $1m, the study calculated, the discount has dropped from 33% in the 1970s to 8% after 2010.

If you not wealthy and wish to collect art, buy textiles, they are much cheaper and very often the creators are women rather than men. They are not as a whole less aesthetically valuable than paintings, except perhaps for paintings at the very very highest levels. But within painting, prices for Gwen John vs. Augustus John have been in parity for some while now, same with Frida Kahlo and her male contemporaries, or Natalia Goncharova vs. her peers, the latter I check on a regular basis in fact I was just perusing them today.

Here is The Economist source piece. Here is the original research., “Is gender in the eye of the beholder? Identifying cultural attitudes with art auction prices”, by Renée Adams, Roman Kräussl, Marco Navone and Patrick Verwijmeren.

Google Bans Bail Bond Ads, Invites Regulation

Google: Today, we’re announcing a new policy to prohibit ads that promote bail bond services from our platforms. Studies show that for-profit bail bond providers make most of their revenue from communities of color and low income neighborhoods when they are at their most vulnerable, including through opaque financing offers that can keep people in debt for months or years.

Google’s decision to ban ads from bail bond providers is deeply disturbing and wrongheaded. Bail bonds are a legal service. Indeed, they are a necessary service for the legal system to function. It’s not surprising that bail bonds are used in communities of color and low income neighborhoods because it is in those neighborhoods that people most need to raise bail. We need not debate whether that is due to greater rates of crime or greater discrimination or both. Whatever the cause, preventing advertising doesn’t reduce the need to pay bail it simply makes it harder to find a lender. Restrictions on advertising in the bail industry, as elsewhere, are also likely to reduce competition and raise prices. Both of these effects mean that more people will find themselves in jail for longer.

As with any industry, there are bad players in the bail bond industry but in my experience the large majority of providers go well beyond lending money to providing much needed services to help people navigate the complex, confusing and intimidating legal system. Sociologist Joshua Page worked as a bail agent:

In the course of my research, I learned that agents routinely offer various forms of assistance for low-income customers, primarily poor people of color. It’s very difficult for those with limited resources to get information, much less support, from overburdened jails, courts, or related institutions. Lacking attentive private attorneys, therefore, desperate defendants and their friends and families turn to bail companies to help them understand and navigate the opaque, confusing legal processes.

…In fact, even when people have gone through it before, the pretrial process can be murky and intimidating….[A]long with walking clients through the legal process, agents explain the differences between public and private attorneys and the relative merits of each. Discussions regularly turn to the defendant’s case: Is the alleged victim pressing charges? Will the case move forward if he or she does not? When is the next court date? If convicted, what’s the likely punishment? Any chance the charges will get dropped?

…In a classic 1975 study, sociologist Forrest Dill argued:

One of the key functions performed by attorneys in the criminal process is to direct the passage of cases through the procedural and bureaucratic mazes of the court system. For unrepresented defendants, however, the bondsman may perform the crucial institutional task of helping to negotiate court routines.

Dill’s observation still rings true: bail agents and administrative staff (at least in Rocksville) act as legal guides for defendants who do not have private attorneys—and at times they provide this help to defendants with inattentive hired counsel. They provide information about court dates and locations, check the status of warrants, contact court staff on defendants’ behalf (especially when the accused have missed court or are at risk of doing so), and, at times, drive defendants to their court dates. These activities help clients show up for court, thereby protecting the company’s investments.

The bail agents are not purely altruistic, they are in a competitive, service business and it pays to help their clients with kindness and care. When I asked one bail agent why he was so polite to his clients and their relations–even when they had jumped bail–he told me, “we rely a lot on repeat business.”

Ian Ayres and Joel Waldfogel also found that the bail bond system can (modestly) ameliorate judicial racial bias. Ayres and Waldfogel found that in New Haven in the 1990s black and Hispanic males were assigned bail amounts that were systematically higher than equally-risky whites. The bail bondpersons, however, offered lower prices to minorities–meaning equal net prices for people of equal risk–exactly what one would expect from a competitive industry.

My own research found that defendants released on commercial bail were much more likely to show up for trial than statistical doppelgangers released by other methods. Bounty hunters were also much more likely than the police to capture and bring to justice people who did jump bail. The bail bond system thus provides an important public service at no cost to the public.

In addition to being wrongheaded, Google’s decision is disturbing because it is so obviously a political decision. Google has banned legal services like bail bonding and payday lending from advertising on Google in order to curry favor with groups who have an ideological aversion to payday lending and the bail system. Google is a private company so this is their right. But every time Google acts as a lawgiver instead of an open platform it invites regulation and political control. Politicians on both sides will see that Google’s code is either a quick-step to political power without the necessity of a vote or a threat to such power. Personally, I don’t want to see greater regulation but if, for example, conservatives decide that Google doesn’t represent their values and threatens their interests, they will regulate.

Google’s decision to use its code as law is an invitation to politicization. Moreover, Google is throwing away its best defense against politicization–the promise of neutrality and openness.

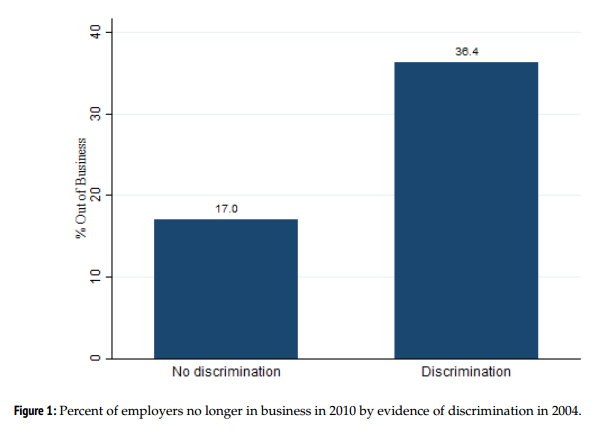

Firms that Discriminate are More Likely to Go Bust

Discrimination is costly, especially in a competitive market. If the wages of X-type workers are 25% lower than those of Y-type workers, for example, then a greedy capitalist can increase profits by hiring more X workers. If Y workers cost $15 per hour and X workers cost $11.25 per hour then a firm with 100 workers could make an extra $750,000 a year. In fact, a greedy capitalist could earn more than this by pricing just below the discriminating firms, taking over the market, and driving the discriminating firms under. The basic logic of employer wage discrimination was laid out by Becker in 1957. The logic implies that discrimination is costly, especially in the long-run, not that it doesn’t happen.

A nice test of the theory can be found in a paper just published in Sociological Science, Are Business Firms that Discriminate More Likely to Go Out of Business? The author, Devah Pager, is a pioneer in using field experiments to study discrimination. In 2004, she and co-authors, Bruce Western and Bart Bonikowski, ran an audit study on discrimination in New York using job applicants with similar resumes but different races and they found significant discrimination in callbacks. Now Pager has gone back to that data and asks what happened to those firms by 2010? She finds that 36% of the firms that discriminated failed but only 17% of the non-discriminatory firms failed.

A nice test of the theory can be found in a paper just published in Sociological Science, Are Business Firms that Discriminate More Likely to Go Out of Business? The author, Devah Pager, is a pioneer in using field experiments to study discrimination. In 2004, she and co-authors, Bruce Western and Bart Bonikowski, ran an audit study on discrimination in New York using job applicants with similar resumes but different races and they found significant discrimination in callbacks. Now Pager has gone back to that data and asks what happened to those firms by 2010? She finds that 36% of the firms that discriminated failed but only 17% of the non-discriminatory firms failed.

The sample is small but the results are statistically significant and they continue to hold controlling for size, sales, and industry.

As Pager notes, the cause of the business failure might not be the discrimination per se but rather that firms that discriminate are hiring using non-rational, gut feelings while firms that don’t discriminate are using more systematic and rational methods of hiring.

As she concludes:

…whether because of discrimination or other associated decision making, we can more confidently conclude that the kinds of employers who discriminate are those more likely to go out of business. Discrimination may or may not be a direct cause of business failure, but it seems to be a reliable indicator of failure to come.

*Why Muslim Integration Fails in Christian-Heritage Societies*

That is the new book by Claire Adida, David Laitin, and Marie-Anne Valfort. Some parts are interesting, especially those showing both statistical and taste-based discrimination against Muslims in France. But most of the book — above all the title — makes claims which are far too strong. A better description would have been “Why France Has Not Integrated Its Muslims.”

To cite one obvious problem, the book only offers four pages of text on Muslim integration in America, a relatively successful venture. And most of those four pages deal with Detroit. The authors’ own evidence just doesn’t seem so damning, for instance when it comes to “Proud to be an American,” on a scale of one to four, Arab Christians come in at 3.67 for the first generation, and 3.75 for the second or third generation. Arab Muslims come in at 3.47 for the first generation, and 3.52 for the second or third generation. Not perfect to be sure, but is that evidence of a massive problem?

There is no talk of Pakistanis in America, a highly successful group with a median income higher than for America as a whole. Nor is there a peep about Bosnian-Americans, who are mostly Muslim and fairly well integrated. How about Iranians, a very successful group in America?

The word “Canada” does not appear in the index of this book.

I could go on. C’mon people, you can do better than this…

Racist tips?

We collected data on over 1000 taxicab rides in New Haven, CT in 2001. After controlling for a host of other variables, we find two potential racial disparities in tipping: (1) African-American cab drivers were tipped approximately one-third less than white cab drivers; and (2) African-American passengers tipped approximately one-half the amount of white passengers (African-American passengers are 3.7 times more likely than white passengers to leave no tip).

Many studies have documented seller discrimination against consumers, but this study tests and finds that consumers discriminate based on the seller’s race. African-American passengers also participated in the racial discrimination. While African-American passengers generally tipped less, they also tipped black drivers approximately one-third less than they tipped white drivers.

The finding that African-American passengers tend to tip less may not be robust to including better controls for passenger social class. But it is still possible to test for the racialized inference that cab drivers (who also could not directly observe passenger income) might make. Regressions suggest that a "rational" statistical discriminator would expect African Americans to tip 56.5% less than white passengers.

I’ve read the abstract but not yet the paper. Note the authors wish to ban tipping [NB: they call it mandatory tipping] to limit racism. Thanks to Mitch Berkson for the pointer.