Results for “zero marginal product” 119 found

What are humans still good for? The turning point in Freestyle chess may be approaching

Some of you will know that Average is Over contains an extensive discussion of “freestyle chess,” where humans can use any and all tools available — most of all computers and computer programs — to play the best chess game possible. The book also notes that “man plus computer” is a stronger player than “computer alone,” at least provided the human knows what he is doing. You will find a similar claim from Brynjolfsson and McAfee.

Computer chess expert Kenneth W. Regan has compiled extensive data on this question, and you will see that a striking percentage of the best or most accurate chess games of all time have been played by man-machine pairs. Ken’s explanations are a bit dense for those who don’t already know chess, computer chess, Freestyle and its lingo, but yes that is what he finds, click on the links in his link for confirmation. In this list for instance the Freestyle teams do very very well.

Average is Over also raised the possibility that, fairly soon, the computer programs might be good enough that adding the human to the computer doesn’t bring any advantage. (That’s been the case in checkers for some while, as that game is fully solved.) I therefore was very interested in this discussion at RybkaForum suggesting that already might be the case, although only recently.

Think about why such a flip might be in the works, even though chess is far from fully solved. The “human plus computer” can add value to “the computer alone” in a few ways:

1. The human may in selective cases prune variations better than the computer alone, and thus improve where the computer searches for better moves and how the computer uses its time.

2. The human can see where different chess-playing programs disagree, and then ask the programs to look more closely at those variations, to get a leg up against the computer playing alone (of course this is a subset of #1). This is a biggie, and it is also a profound way of thinking about how humans will add insight to computer programs for a long time to come, usually overlooked by those who think all jobs will disappear.

3. The human may be better at time management, and can tell the program when to spend more or less time on a move. “Come on, Rybka, just recapture the damned knight!” Haven’t we all said that at some point or another? I’ve never regretted pressing the “Move Now” button on my program.

4. The human knows the “opening book” of the computer program he/she is playing against, and can prepare a trap in advance for the computer to walk into, although of course advanced programs can to some extent “randomize” at the opening level of the game.

Insofar as the above RybkaForum thread has a consensus, it is that most of these advantages have not gone away. But the “human plus computer” needs time to improve on the computer alone, and at sufficiently fast time controls the human attempts to improve on the computer may simply amount to noise or may even be harmful, given the possibility of human error. Some commentators suggest that at ninety minutes per game the humans are no longer adding value to the human-computer team, whereas they do add value when the time frame is say one day per move (“correspondence chess,” as it is called in this context.) Circa 2008, at ninety minutes per game, the best human-computer teams were better than the computer programs alone. But 2013 or 2014 may be another story. And clearly at, say, thirty or sixty seconds a game the human hasn’t been able to add value to the computer for some time now.

Note that as the computer programs get better, some of these potential listed advantages, such as #1, #3, and #4 become harder to exploit. #2 — seeing where different programs disagree — does not necessarily become harder to exploit for advantage, although the human (often, not always) has to look deeper and deeper to find serious disagreement among the best programs. Furthermore the ultimate human sense of “in the final analysis, which program to trust” is harder to intuit, the closer the different programs are to perfection. (In contrast, the human sense of which program to trust is more acute when different programs have more readily recognizable stylistic flaws, as was the case in the past: “Oh, Deep Blue doesn’t always understand blocked pawn formations very well.” Or “Fritz is better in the endgame.” And so on.)

These propositions all require more systematic testing, of course. In any case it is interesting to observe an approach to the flip point, where even the most talented humans move from being very real contributors to being strictly zero marginal product. Or negative marginal product, as the case may be.

And of course this has implications for more traditional labor markets as well. You might train to help a computer program read medical scans, and for thirteen years add real value with your intuition and your ability to revise the computer’s mistakes or at least to get the doctor to take a closer look. But it takes more and more time for you to improve on the computer each year. And then one day…poof! ZMP for you.

Addendum: Here is an article on computer dominance in rock-paper-scissors. This source claims freestyle does not beat the machine in poker.

ZMP workers and morale externalities

On Twitter, Bryan Caplan asks me to clarify why zero marginal product workers do not clash with the notion of comparative advantage. The point is simple: some workers destroy a lot of morale in the workplace and so the employer doesn’t want them around at any price.

Most of us buy into “morale costs” as a key reason behind sticky nominal wages. If your wage is too low, your morale falls, you produce less and so the wage cut isn’t worth it. Well, what else besides low wages makes people unhappy in their workplace? Very often the quality of co-workers is a major source of unhappiness; just listen to people complain about their jobs and write down how many times they are mentioning co-workers and bosses. (I do not exempt academics here.) A “rotten apple” can make many people less productive, and you can think of that as a simple extension of sticky nominal wage theory, namely that installing or tolerating a “pain in the ass” is another way of cutting wages for the good workers, they don’t like it, it lowers their productivity, and thus it is not worth tolerating the rotten apple if said apple can be identified and dismissed.

There is no particular reason to think that ZMP workers are especially stupid or in some way “disabled.” If anything it may require some special “skills” to get under people’s skins so much. (Of course there are some individuals who, say for health reasons, cannot produce anything at all but they are not usually in or “near” the active labor force.) To draw a simple analogy, the lowest-publishing members of academic departments are rarely those who make the most trouble.

To the extent production becomes more complex and more profitable, ZMP workers are more of a problem because there is more value they can destroy. The relevance of these morale costs also varies cyclically, in standard fashion. A company is more likely to tolerate a “pain” in boom times when the labor itself has a higher return.

Note also the “expected ZMP worker.” Let’s say that some ZMPers destroy a lot of value (that makes them NMPers). You pay 40k a year and you end up with a worker who destroys 80k a year, so the firm is out 120k net. Bosses really want to avoid these employees. Furthermore let’s say that a plague of these destructive workers hangs out in the pool of the long-term unemployed, but they constitute only 1/3 of that pool, though they cannot easily be distinguished at the interview stage. 1/3 a chance of getting a minus 120k return will scare a lot of employers away from the entire pool. The employers are behaving rationally, yet it can be said that “there is nothing wrong with most of the long-term unemployed.” And still they can’t get jobs and still nominally eroding the level of wages won’t help them.

In the perceived, statistical, expected value sense, the lot of these workers is that of ZMPers.

One policy implication is that it should become legally easier to offer a very negative recommendation for a former employee. That makes it easier to break the pooling equilibrium. There also are equilibria where it makes sense to “buy the NMPers out” of workforce participation altogether, pay them to emigrate, etc., although such policies may be difficult to implement. Oddly, if work disincentives target just the right group of people — the NMPers — (again, hard to do, but worth considering the logic of the argument) those disincentives can raise the employment/population ratio, at least in theory.

Addendum: Garett Jones offers yet a differing option for understanding ZMP theories.

More on countercyclical restructuring and ZMP

I have been reading some new results by David Berger (who by the way seems to be an excellent job market candidate, from Yale), here is one bit:

Finally, I discuss what changed in the 1980s. I provide suggestive evidence that the structural change was the result of a large decline in union power in the 1980s. This led to a sharp reduction in the restrictions firms faced when adjusting employment, which lowered fi ring costs and made it easier for fi rms to fire selectively. I test this hypothesis using variation from U.S. states and industries. I show that states and industries that had larger percentage declines in union coverage rates had larger declines in the cyclicality of ALP [average labor productivity], consistent with my hypothesis. The union power hypothesis is also consistent with evidence from detailed industry studies. A recent paper by Dunne, Klimek and Schmitz (2010) shows that there were dramatic changes in the structure of union contracts in the U.S. cement industry in the early-1980s, which gave establishments much more scope to fire workers based on performance rather than tenure. They show that immediately after these workplace restrictions were lifted, ALP and TFP in the industry increased signifi cantly.

This paper is a goldmine of information on the cyclical behavior of productivity and how it has changed in recent times. Basically, we’re now at the point where a recession means they dump the bad workers and we subsequently have a jobless recovery.

While we’re on the broader topic, I’d like to make a few points about the recent ZMP (“zero marginal productivity“) debates between Kling, Caplan, Henderson, Boudreaux, and Eli Dourado:

1. There has been plenty of evidence for “labor hoarding”; oddly, once the ZMP workers start actually being fired, the concept suddenly becomes controversial. The simple insight is that firms don’t hoard so much labor any more.

2. The ZMP worker concept can overlap with the sticky wage concept. If a person is a prima donna who will sabotage production unless paid 120k a year and given the best office, that person has a sticky wage. That same person also can be ZMP. Very often the concept is about bad morale, not literal and universal incompetence; the ZMPers are often quite effective at sabotage!

3. No one thinks a worker is ZMP in all possible world-states.

4. The high and rising premium for good managers is another lens for viewing the phenomenon. More workers could usefully be employed if we had more skilled supervisors, and thus the shadow value for a skilled supervisor is especially high.

5. Virtually everyone believes in the concept, although opinions differ as to how many workers it covers. How about the people who are classified as having given up the search for work altogether? There’s quite a few of them. Put aside the blame question and the moralizing, can’t at least a few of these people — who aren’t even looking to work — be considered ZMP?

In any case, Berger’s concerns are more empirical and more concrete than some of the issues in those debates. At the first link you also can find some very interesting papers, by Berger, on the cyclical behavior of price stickiness. The observed data — surprise, surprise — are quite inconsistent with standard models.

Robin Hanson is forming a forecasting team, Kling and Schulz have a new edition

In response to the Philip Tetlock forecasting challenge, Robin is responding:

Today I can announce that GMU hosts one of the five teams, please join us! Active participants will earn $50 a month, for about two hours of forecasting work. You can sign up here, and start forecasting as soon as you are accepted.

There is more detail at the link. Let’s see if he turns away the zero marginal product workers.

There is also a new paperback edition out of the excellent Arnold Kling and Nick Schulz book out, now entitled Invisible Wealth: The Hidden Story of How Markets Work. The book has new forecasts…

What does the new gdp report imply for structural explanations of our current troubles?

How should we revise structural interpretations of unemployment in light of the new gdp revisions? (For summaries, here are a few economists’ reactions to the report.) Just to review briefly, I find the most plausible structural interpretations of the recent downturn to be based in the “we thought we were wealthier than we were” mechanism, leading to excess enthusiasm, excess leverage, and an eventual series of painful contractions, both AS and AD-driven, to correct the previous mistakes. I view this hypothesis as the intersection of Fischer Black, Hyman Minsky, and Michael Mandel.

A key result of the new numbers is that we had been overestimating productivity growth during a period when it actually was feeble. That is not only consistent with this structural view but it plays right into it: the high productivity growth of 2007-2009 now turns out to be an illusion and indeed the structural story all along was suggesting we all had illusions about the ongoing rate of productivity growth. As of even a mere few days ago, some of those illusions were still up and running (are they all gone now? I doubt it.)

On one specific, it is quite possible that the new numbers diminish the relevance of the zero marginal product (ZMP) worker story. The ZMP worker story tries to match the old data, which showed a lot of layoffs and skyrocketing per hour labor productivity in the very same or immediately succeeding quarters. Those numbers, taken literally, imply that the laid off workers were either producing very little to begin with or they were producing for the more distant future, a’la the Garett Jones hypothesis. The new gdp numbers will imply less of a boom in per hour labor productivity in the period when people are fired in great numbers, though I would be surprised if the final adjustments made this initially stark effect go away. BLS estimates from June 2011 still show quite a strong ZMP effect, although you can argue the final numbers for that series are not yet in. (I don’t see the relevant quarterly adjustments for per hour labor productivity in the new report, which comes from Commerce, not the BLS.) Furthermore there is plenty of evidence that the unemployed face “discrimination” when trying to find a new job. Finally, the strange and indeed relatively new countercyclicality of labor productivity also occurred in the last two recessions and it survived various rounds of data revisions. It would be premature — in the extreme — to conclude we’ve simply had normal labor market behavior in this last recession. That’s unlikely to prove the result.

Most generally, the ZMP hypothesis tries to rationalize an otherwise embarrassing fact for the structural hypothesis, namely high measured per hour labor productivity in recent crunch periods. If somehow that measure were diminished, that helps the structural story, though it would make ZMP less necessary as an auxiliary hypothesis, some would say fudge.

Other parts of the structural story find ready support in the revisions. Real wealth has fallen and so consumers have much less interest in wealth-elastic goods and services. This shows up most visibly in state and local government employment, which has fallen sharply since the beginning of the recession. Rightly or wrongly, consumers/voters view paying for these jobs as a luxury and so their number has been shrinking. Construction employment is another structural issue, and given the negative wealth effect, and the disruption of previously secure plans, there is no reason to expect excess labor demand in many sectors.

In the new report “profits before tax” are revised upward for each year. That further supports the idea of a whammy falling disproportionately on labor and the elimination of some very low product laborers.

Measured real rates of return remain negative, which is very much consistent with a structural story. Multi-factor productivity remains miserably low. In my view, a slow recovery was in the cards all along. Finally, you shouldn’t take any of this to deny the joint significance of AD problems; AS and AD problems have very much compounded each other.

From the Richmond Fed, on structural unemployment

These results are related to what I sometimes call Zero Marginal Product workers:

…a significant part of the increase in long-term unemployment is indeed due to the inflow into unemployment of workers with relatively low job finding rates. We conclude by arguing that given the increased contribution to overall unemployment of unemployed workers with inherently low job finding rates, monetary policymakers may want to exercise caution in the use of policy to respond to the level of unemployment.

The authors are Andreas Hornstein and Thomas A. Lubik. The entire study — full of useful information — is here, and for the pointer I thank Alex in Jerusalem (we await a report).

Via Scott Sumner, while this is not my favorite structural explanation, I read of this from Siemens:

Siemens had been forced to use more than 30 recruiters and hire staff from other companies to find the workers it needed for its expansion plans, even amid an unemployment rate of 9.1 percent

…a recent survey from Manpower, the employment agency, found that 52 percent of leading US companies reported difficulties in recruiting essential staff, up from 14 percent in 2010.

In manufacturing in particular there is evidence of a mismatch between workforce skills and available jobs: while employment has fallen since January 2009, the number of available job openings has risen from 98,000 to 230,000.

Via Felix Salmon (he pulls out excellent pictures), from the IMF, using cross-country data:

For U.S. long-term unemployment the split between cyclical and structural factors is closer to 60-40, including during the Great Recession.

Karl Smith on aggregate demand

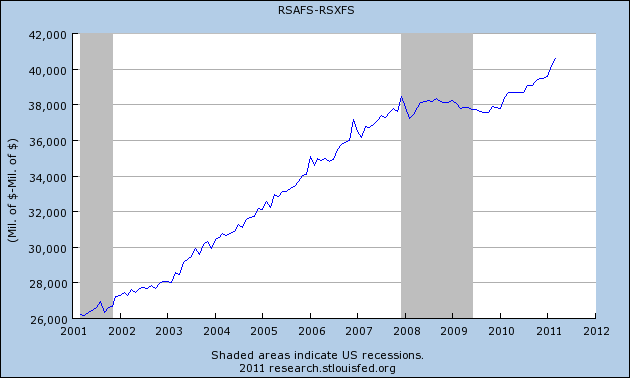

It is an excellent post, read the whole thing. To pull out one point, here is the hospitality sector, expressed in levels:

It’s clearly below trend, had there been no financial crisis. But will sticky nominal wages cause significant unemployment? In terms of absolute levels, business is above where it was before the crisis. At first glance, that should seem enough to support the nominal wage levels of 2007. You also can see that the initial downward dip really doesn’t last for long (two months?) before the older absolute level of business activity is restored.

One approach is to place a lot of the explanatory power in the labor market lags, thereby invoking real variables, above-average risk premia and option values, zero marginal product workers, credit constraints, and so on.

To save an AD story for this sector, one might try the “wandering relative prices” add-on. This graph shows an aggregate. As time passes, especially when AD is relatively stagnant, some prices in this sector fall quite a bit, more so than is indicated by measures of totals or averages. The more that some prices are otherwise inclined to “wander” quite low, the more that rising nominal expenditure flows are required to keep demands high enough so that those sectors aren’t faced with having to cut nominal wages.

The funny thing is, the data on relative prices don’t exactly fit the standard Keynesian story; read this excellent post by Stephen Williamson.

Basically, it’s complicated.

Assorted links

1. How to avoid a gendered conference; at first I thought this was a Straussian satire by a confirmed chauvinist.

2. Yakuza step forward with relief supplies.

3. Zero marginal product Frank Lloyd Wright homes?

4. Persistent wage disparities in Britain are due to people rather than place.

ZMP v. Sticky Wages

I find myself in the unusual position of being closer to Paul Krugman (and Scott Sumner, less surprising) than Tyler on the question of Zero Marginal Product workers.

The ZMP hypothesis is too close to a rejection of comparative advantage for my tastes. The term ZMP also suggests that the problem is the productivity of the unemployed when the actual problem is with the economy more generally (a version of the fundamental attribution error).

To see the latter point note that even within the categories of workers with the highest unemployment rates (say males without a high school degree) usually a large majority of these workers are employed. Within the same category are the unemployed so different from the employed? I don't think so. One reason employed workers are still fearful is that they see the unemployed and think, "there but for the grace of God, go I." The employed are right to be fearful, being unemployed today has less to do with personal characteristics than a bad economy and bad luck (including the luck of being in a declining sector, I do not reject structural unemployment).

To see the importance of sticky wages consider the following thought experiment: Imagine randomly switching an unemployed worker for a measurably similar employed worker but at say a 15% lower wage. Holding morale and other such factors constant, do you think that employers would refuse such a switch? Tyler says yes. I say no. If wages were less sticky the unemployed would be find employment

By the way, the problem of sticky wages is often misunderstood. The big problem is not that the wages of unemployed workers are sticky, the big problem is that the wages of employed workers are sticky. This is why stories of the unemployed being reemployed at far lower wages are entirely compatible with the macroeconomics of sticky wages.

Although I don't like the term ZMP workers, I do think Tyler is pointing to a very important issue: firms used to engage in labor hoarding during a recession and now firms are labor disgorging. As a result, labor productivity has changed from being mildly pro-cyclical to counter-cyclical. Why? I can think of four reasons. 1) The recession is structural, as Tyler has argued. If firms don't expect to ever hire workers back then they will fire them now. 2) Firms expect the recession to be long – this is consistent with a Scott Sumner AD view among others. 3) In a balance-sheet recession firms are desperate to reduce debt and they can't borrow to labor hoard. 4) Labor markets have become more competitive. Firms used to be monopsonists and so they would hold on to workers longer since W<MRP. Now that cushion is gone and firms fire more readily. What other predictions would this model make?

It would be interesting to know why Paul Krugman thinks productivity has become counter-cyclical but I believe he has yet to address this important topic.

Addendum: Paul Krugman gives his answer and The Economist offers a review with many links.

Cowen and Lemke, on employment

…Before the financial crash, there were lots of not-so-useful workers holding not-so-useful jobs. Employers didn't so much bother to figure out who they were. Demand was high and revenue was booming, so rooting out the less productive workers would have involved a lot of time and trouble — plus it would have involved some morale costs with the more productive workers, who don't like being measured and spied on. So firms simply let the problem lie.

Then came the 2008 recession, and it was no longer possible to keep so many people on payroll. A lot of businesses were then forced to face the music: Bosses had to make tough calls about who could be let go and who was worth saving. (Note that unemployment is low for workers with a college degree, only 5 percent compared with 16 percent for less educated workers with no high school degree. This is consistent with the reality that less-productive individuals, who tend to have less education, have been laid off.)

In essence, we have seen the rise of a large class of "zero marginal product workers," to coin a term. Their productivity may not be literally zero, but it is lower than the cost of training, employing, and insuring them. That is why labor is hurting but capital is doing fine; dumping these employees is tough for the workers themselves — and arguably bad for society at large — but it simply doesn't damage profits much. It's a cold, hard reality, and one that we will have to deal with, one way or another.

The solution? Here is a paragraph which did not make the final editing cut:

…being unproductive in one job doesn’t mean a lifetime of unemployment. A worker who wasn’t worth much sweeping up the back room is suddenly valuable when new orders are flowing in and he is needed to ship the goods out the door. And if all those new orders require keeping the warehouse open late, the company may need to bring in a new night watchman. To paraphrase a common metaphor, a rising tide eventually lifts most boats. When the economy’s expanding, a worker who previously was worthless will at some point become valuable again. But this means that workers at the bottom of the economic ladder will have to wait until the entire economy has mended itself before they have the chance to improve their lot: That can be a painstakingly slow and uncertain process.

Declines in demand and how to disaggregate them

Let’s say that housing and equity values fall and suddenly people realize they are less wealthy for the foreseeable future. The downward shift of demand will bundle together a few factors:

1. A general decline in spending.

2. A disproportionate and permanent demand decline for the more income- and wealth-elastic goods, a category which includes many consumer durables and also luxury goods. (Kling on Leamer discusses relevant issues.)

3. A disproportionate and temporary demand decline for consumer durables, which will largely be reversed once inventories wear out or maybe when credit constraints are eased.

Those are sometimes more useful distinctions than “AD” vs. “sectoral shocks,” because AD shifts consist of a few distinct elements.

If you see #1 as especially important, you will be relatively optimistic about monetary and fiscal stimulus. If you see #2 as especially important, you will be relatively pessimistic. You can call #2 an “AD shift” if you wish, but reflation won’t for the most part bring those jobs back. People need to be actually wealthier again, in real terms, for those spending patterns to reemerge in a sustainable way. Stimulus proponents regularly conflate #1 and #2 and cite “declines in demand” as automatic evidence for #1 when they might instead reflect #2.

If you see #3 as especially important, and see capital markets as imperfect in times of crisis, you will consider policies such as the GM bailout to be more effective than fiscal stimulus in its ramp-up forms.

Sectoral shift advocates like to think in terms of #2, but if #3 lurks the shifts view can imply a case for some real economy interventions. I read Arnold Kling as wanting to dance with #2 but keep his distance from #3. But if permanent sectoral shifts are important, might not the temporary shifts (we saw the same whipsaw patterns in international trade) be very important too? Can we embrace #2 without also leaning into #3?

I wish to ask this comparative question without having to also rehearse all of the ideological reasons for and against real economy bailouts. It gets at why the GM bailout has gone better than the fiscal stimulus, a view which you can hold whether you favor both or oppose both.

Note there also (at least) two versions of the sectoral shift view and probably both are operating. The first cites #2. The second claims some other big change is happening, such as the move to an internet-based economy. If both are happening at the same time, along with some #1 and some #3, that probably makes the recalculation problem especially difficult.

I see another real shock as having been tossed into the mix, namely that liquidity constraints have forced many firms to identify and fire the zero and near-zero marginal productivity workers.

There’s also the epistemic problem of whether we have #2 or #3 and whether we trust politics to tell the difference.

The Germans had lots of #3 (temporary whacks to their export industries) and treated them as such, whether consciously or not, and with good success. Arguably Singapore falls into that camp as well. The U.S. faces more serious identification problems, whether at the level of policy or private sector adjustment. We have not been able to formulate policy simply by assuming that we face a lot of #3.

I would have more trust in current applied policy macroeconomics if we could think through more clearly the relative importances of #1, 2, and 3. And when I hear the phrase “aggregate demand,” immediately I wonder whether it all will be treated in aggregate fashion; too often it is.

*Winter’s Bone*

It's the best movie we're likely to get this year. It also has plenty of social science, including "the costs of cooperation," and zero marginal product labor.

SuperFreakonomics on Geoengineering, Revisited

Geoengineering first came to much of the public’s attention in Levitt and Dubner’s 2009 book SuperFreakonomics. Levitt and Dubner were heavily criticized and their chapter on geoengineering was called patent nonsense, dangerous and error-ridden, unforgivably wrong and much more. A decade and a half later, it’s become clear that Levitt and Dubner were foresighted and mostly correct.

The good news is that climate change is a solved problem. Solar, wind, nuclear and various synthetic fuels can sustain civilization and put us on a long-term neutral footing. Per capita CO2 emissions are far down in developed countries and total emissions are leveling for the world. The bad news is that 200 years of putting carbon into the atmosphere still puts us on a warming trend for a long time. To deal with the immediate problem there is probably only one realistic and cost-effective solution: geoengineering. Geoengineering remains “fiendishly simple” and “startlingly cheap” and it will almost certainly be necessary. On this score, the world is catching up to Levitt and Dubner.

Fred Pearce: Once seen as spooky sci-fi, geoengineering to halt runaway climate change is now being looked at with growing urgency. A spate of dire scientific warnings that the world community can no longer delay major cuts in carbon emissions, coupled with a recent surge in atmospheric concentrations of CO2, has left a growing number of scientists saying that it’s time to give the controversial technologies a serious look.

“Time is no longer on our side,” one geoengineering advocate, former British government chief scientist David King, told a conference last fall. “What we do over the next 10 years will determine the future of humanity for the next 10,000 years.”

King helped secure the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, but he no longer believes cutting planet-warming emissions is enough to stave off disaster. He is in the process of establishing a Center for Climate Repair at Cambridge University. It would be the world’s first major research center dedicated to a task that, he says, “is going to be necessary.”

Similarly, here is climate scientist David Keith in the NYTimes:

The energy infrastructure that powers our civilization must be rebuilt, replacing fossil fuels with carbon-free sources such as solar or nuclear. But even then, zeroing out emissions will not cool the planet. This is a direct consequence of the single most important fact about climate change: Warming is proportional to the cumulative emissions over the industrial era.

Eliminating emissions by about 2050 is a difficult but achievable goal. Suppose it is met. Average temperatures will stop increasing when emissions stop, but cooling will take thousands of years as greenhouse gases slowly dissipate from the atmosphere. Because the world will be a lot hotter by the time emissions reach zero, heat waves and storms will be worse than they are today. And while the heat will stop getting worse, sea level will continue to rise for centuries as polar ice melts in a warmer world. This July was the hottest month ever recorded, but it is likely to be one of the coolest Julys for centuries after emissions reach zero.

Stopping emissions stops making the climate worse. But repairing the damage, insofar as repair is possible, will require more than emissions cuts.

…Geoengineering could also work. The physical scale of intervention is — in some respects — small. Less than two million tons of sulfur per year injected into the stratosphere from a fleet of about a hundred high-flying aircraft would reflect away sunlight and cool the planet by a degree. The sulfur falls out of the stratosphere in about two years, so cooling is inherently short term and could be adjusted based on political decisions about risk and benefit.

Adding two million tons of sulfur to the atmosphere sounds reckless, yet this is only about one-twentieth of the annual sulfur pollution from today’s fossil fuels.

Even the Biden White House has signaled that geoengineering is on the table.

Geoengineering remains absurdly cheap, Casey Handmer calculates:

Indeed, if we want to offset the heat of 1 teraton of CO2, we need to launch 1 million tonnes of SO2 per year, costing just $350m/year. This is about 5% of the US’ annual production of sulfur. This costs less than 0.1% on an annual basis of the 40 year program to sequester a trillion tonnes of CO2.

…Stepping beyond the scolds, the gatekeepers, the fatalists and the “nyet” men, we’re going to have to do something like this if we don’t want to ruin the prospects of humanity for 100 generations, so now is the time to think about it.

Detractors claim that geoengineering is playing god, fraught with risk and uncertainty. But these arguments are riddled with omission-commission bias. Carbon emissions are, in essence, a form of inadvertent geoengineering. Solar radiation engineering, by comparison, seems far less perilous. Moreover, we are already doing solar radiation engineering just in reverse: International regulations which required shippers to reduce the sulphur content of marine fuels have likely increased global warming! (See also this useful thread.) . Thus, we’re all geoengineers, consciously or not. The only question is whether we are geoengineering to reduce or to increase global warming.

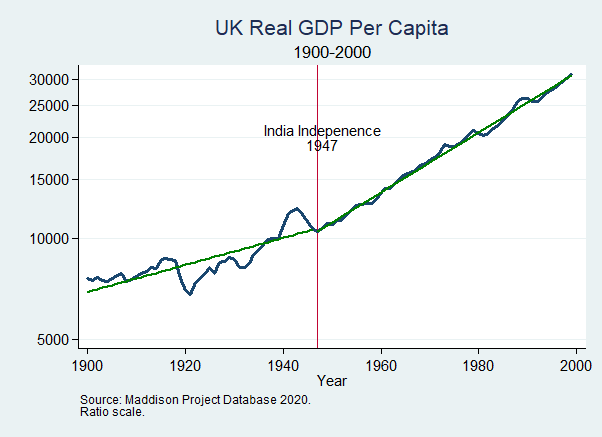

Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and a scant ten years later, India gained its independence. Thus, we have a clear prediction. Was England reduced to living mainly on herrings and potatoes after Indian Independence? No. In fact, not only did the UK continue to get rich after the end of empire, the growth rate of GDP increased.

Orwell’s failed prediction stemmed from two reasons. First, he was imbued with zero-sum thinking. It should have been obvious that India was not necessary to the high standard of living enjoyed in England because most of that high standard of living came from increases in the productivity of labor brought about capitalism and the industrial revolution and most of that was independent of empire (Most. Maybe all. Maybe more more than all. Maybe not all. One can debate the finer details on financing but of that debate I have little interest.) The second, related reason was that Orwell had a deep suspicion and distaste for technology, a theme I will take up in a later post.

Orwell, who was born in India and learned something about despotism as a police officer in Burma, opposed empire. Thus, his argument that we had to be poor to be just was a tragic dilemma, one of many that made him pessimistic about the future of humanity.

Nathan Labenz on AI pricing

I won’t double indent, these are all his words:

“I agree with your general take on pricing and expect prices to continue to fall, ultimately approaching marginal costs for common use cases over the next couple years.

A few recent data points to establish the trend, and why we should expect it to continue for at least a couple years…

- OpenAI reduced core LLM pricing by 2/3rds last year.

- StabilityAI has recently reduced prices on Stable Diffusion down to a base of $0.002 / image – now you get 500 images / dollar. This is a >90% reduction from OpenAI’s original DALLE2 pricing.

- OpenAI has also recently reduced their embeddings price by 99.8% – not a typo! You can now index all 200M+ papers on Semantic Scholar for $500K-2M, depending on your approach.

- Emad from StabilityAI projects ~1M fold cost improvement over next 10 years – responding to Chamath who had predicted 1000X improvement

Looking ahead…

- continued application of RLHF and similar techniques – these techniques create 100X parameter advantage (already in use in force at OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google – but limited use elsewhere)

- the CarperAI “Open Instruct” project – also affiliated with (part of?) StabilityAI, aims to match OpenAI’s current production models with an open source model, expected in 2023

- 8-bit and maybe even 4-bit inference – simply by rounding weights off to fewer significant digits, you save memory requirements and inference compute costs with minimal performance loss

- pruning for sparsity – turns out some LLMs work just as well if you set 60% of the weights to zero (though this likely isn’t true if you’re using Chinchilla-optimal training)

- mixture of experts techniques – another take on sparsity, allows you to compute only certain dedicated sub-blocks of the overall network, improving speed and cost

- distillation – a technique by which larger, more capable models can be used to train smaller models to similar performance within certain domains – Replit has a great writeup on how they created their first release codegen model in just a few weeks this way!

- distributed training techniques, including approaches that work on consumer devices, and “reincarnation” techniques that allow you to re-use compute rather than constantly re-training from scratch

And this is all assuming that the weights from a leading model never leak – that would be another way things could quickly get much cheaper… ”

TC again: All worth a ponder, I do not have personal views on these specific issues, of course we will see. And here is Nathan on Twitter.