Results for “no great stagnation” 495 found

Assorted links

1. Critique of TGS, by Kindred Winecoff.

2. Why the epidemic of mental illness and depression?

3. Tugboats and Arctic icebergs.

4. Germany’s Great Stagnation, and David Leonhardt on Germany.

Assorted links

Profile of Tyler

Brendan Greeley of Bloomberg has an excellent profile of Tyler, both amusing and accurate. Here’s one bit:

When Tyler Cowen was 15, he became the New Jersey Open Chess Champion, at the time the youngest ever. At around the same age, he began reading seriously in the social sciences; he preferred philosophy. By 16 he had reached a chess rating of 2350, which today would put him close to the top 100 in the U.S. Shortly thereafter he gave up chess and philosophy for the same reason: little stability and poor benefits.

He’d been reading economics, though. He figured that economists were supposed to publish, and by age 19 he had placed two papers in respected journals. As a PhD candidate at Harvard, he published in the “Journal of Political Economy” and the “American Economic Review.”

“They were weird, strange pieces,” he says, “but still in good journals, top journals. That cemented my view that I could, you know, somehow fit in somewhere.” I ask him what he was like, what made him doubt he could fit in.

“I was like I am now.”

“You’ve always been like that?”

“Always. Age 3. Whatever.”

“What did you do at age 3?”

“Read a lot of books.”

Read the whole thing especially for more on the sociology of the economics profession.

Oh and here is an interesting development, the hot new restaurants are now tweeting about Tyler. Strange world.

Assorted links

1. PBS Newshour segment on The Great Stagnation, including an excellent MIT critique by Erik Brynjolfsson.

2. How David Brooks fits into Britain.

4. Famous science fiction writers recommend science fiction.

6. Tim Harford on unexpected and underappreciated economics books.

Assorted links

1. An environmentalist perspective on The Great Stagnation.

2. A history of Christian rock.

3. Did the stimulus destroy jobs on net? (pdf)

4. The etymology of inflation, and also here.

5. Markets in everything: Barbara’s Bakery Peanut Butter Puffin Cereal.

Assorted links

1. Tyler Cowen, speaking off the cuff, defines friendship, a two minute video.

2. Library of Congress launches National Jukebox.

3. Will data mining end the Great Stagnation? In any case you should major in statistics.

4. German economic growth is surging; again, real factors matter much more than fiscal policy or fiscal austerity.

*The Changing Body*

The authors are Roderick Floud, Nobel Laureate Robert W. Fogel, Bernard Harris, and Sok Chul Hong, and the subtitle is Health, Nutrition, and Human Development in the Western World since 1700. Here is one key sentence:

Chronically malnourished populations of Europe universally responded to food constraints by varying body size.

You can write an important and fascinating 400-page book around that sentence, although it will not hold the attention of all readers. Here is a good summary article (1/20) on the book. Here is another excerpt:

Even if it is assumed that the daily number of calories available for work was the same in the United States in 1860 as today, the intensity of work per hour would have been well below today’s levels, since the average number of hours worked in 1860 was 1.75 times as great as today. During the mid nineteenth century, only slaves on southern gang-system plantations appear to have worked at levels of intensity per hour approaching current standards.

It is interesting to read the authors’ estimates of wage growth from 1750 to about 1820. Some estimates suggest zero growth, while a more optimistic study shows that in Great Britain real wages rose about 12.5 percent between 1770 and 1818, and that was during the Industrial Revolution or should that be “during the so-called Industrial Revolution”? Read this piece by Charles Feinstein; the standard of living for the average working class family increased by only 15 percent from the 1780s to the 1850s. Here is an ungated paper with similar results. Great Stagnation-like phenomena are not new and as Arnold Kling noted recently, theories of technological unemployment may yet make a comeback.

Here are two blue-footed boobies.

Assorted links

1. Restaurants cherry pick parties by size.

2. Interview on the new Tim Harford book.

4. Josh Barro on The Great Stagnation and goofing off.

5. I believe you can watch my Wednesday debate with Roger Scruton here.

6. Philadelphia Orchestra puts subscription money into escrow, not a good sign.

How well is fiscal austerity working in the UK?

With the Wednesday release of a mediocre gdp report, we are hearing that the United Kingdom austerity program is proving a macroeconomic failure.

Let’s look at the timing of the cuts:

So far, about GBP9 billion of the government’s fiscal tightening has occurred. However, around GBP41 billion of tax increases and spending cuts will begin to take affect from the start of the new fiscal year on April 5.

Some of the particular cuts were announced in October and at that time Ken Rogoff doubted whether half of them would end up taking place. So the cuts are in their infancy and arguably their credibility is still somewhat in doubt or at the very least has been.

A lot of the weak gdp report is blamed on construction, with some excuses drawn from snowstorms. There does exist an extreme rational expectations view, in which the last-quarter weakness of construction was based on the expectation that government spending cuts would start arriving later in April and thus new houses should not be built. Alternatively, it could be that after the greatest real estate bubble in history, the UK market is overbuilt. Weak UK growth dates to some time back.

Also recall that in many open economy Keynesian models, fiscal policy AD effects are to some extent — or completely — offset by exchange rate movements (pdf). And the fiscal multiplier is basically zero when the central bank targets inflation. Furthermore it is not obvious that the UK has been in a liquidity trap. When it comes to drawing Keynesian conclusions about practical fiscal policy, the theory here is a house of cards.

The UK economy suffers from a more serious technological stagnation than does the United States, in this case more forward looking than backward looking. Their pharmaceutical innovation seems to be drying up, they are overspecialized in finance, the “residential tax haven” status of the country may not yield continuing growth at high rates, tourism is OK but not enough, and their manufacturing base eroded some time ago, with nothing like a German-style comeback. The teacup sector aside, why should anyone be optimistic about that economy?

Two other considerations:

1. The case for the cuts is not that they will spur growth, but rather forestall a future disaster. That’s hard to test. A second part of the case is that not many political windows for the cuts will be available; that’s hard to test too. On that basis, it’s fine to call the case for the cuts underestablished, but that’s distinct from claiming that poor gdp performance shows the cuts to be a mistake.

2. Let’s say the cuts lower government consumption and raise private consumption, and that government consumption is wasteful but private consumption isn’t (and long-run growth is given by the Solow-like expansion of the international technological frontier.) That’s a good case for making the cuts, but they still won’t show up as higher gdp. The government consumption is valued into gdp figures at cost, so even cuts proponents with a good case don’t have to be predicting higher gdp.

I doubt if the UK fiscal austerity program will much boost their growth rate, which is likely low in any case and for non-Keynesian reasons. Simply citing a low UK growth rate is not a test of their fiscal policy, for a number of reasons detailed above.

Assorted links

1. Is the black market in metereorite fragments a good or bad development? (NYT)

2. Salamander has algae living inside its cells. And Reihan on Lula.

3. China famine facts of the day.

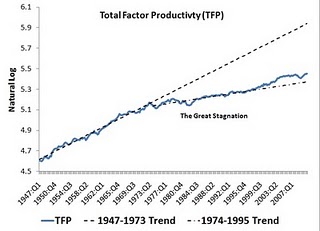

4. Breaking down the decline in TFP; note the importance of sectoral shifts into lower-growing sectors, as discussed here by Gordon Bjork and in the comments by Andy Harless.

5. Dan Gardner on nuclear power.

6. How San Francisco parking pricing will work.

7. How the world’s economic center of gravity has been shifting.

Total Factor Productivity

Assorted links

1. Facebook and TGS, and Robin Hanson reviews TGS. Mike Mandel responds to Karl Smith.

2. Is envy a stronger motivator than admiration?

3. Passing to yourself off the backboard (video).

4. Yet another way of viewing our labor market troubles, or in other words, start-ups have suffered too (NYT blog).

5. Via Chris F. Masse, when will China overtake the U.S. in science? (NB: I’m not convinced by this article).

Assorted links

Assorted links

1. Markets in everything, for Chas.

3. Comment or vote (short video from Jonathan Rauch), “Trolls belong under bridges.”

5. Are the wealthiest countries the smartest countries?

6. Exit interview with Larry Summers.

7. Great Stagnation debate, this coming Monday morning in DC, register here.

Assorted links

1. Is traditional publishing really dead?

2. Is the euro really dead? (Too much on stocks, not enough on flows, to convince me.)

3. Is the stamp really dead? (aka: the culture that is Sweden)

4. Cooperating elephants, and more here.

5. MIE: North Korean food in Annandale, Virginia. And here is study abroad in the Hermit Kingdom.

6. The future of educational reform, by Steve Teles.

7. Robot debates in science fiction.

8. On DeLong and Varian, Reihan gets it right. From DeLong, here is stagnation for thee but not for me.