Results for “"minimum wage"” 290 found

The Evidence Is Piling Up That Higher Minimum Wages Kill Jobs

That is David Neumark in the WSJ, here is one excerpt:

Another recent study by Shanshan Liu and Thomas Hyclak of Lehigh University, and Krishna Regmi of Georgia College & State University most directly mimics the Dube et al. approach. But crucially it only uses as control areas parts of states that are classified by the Bureau of Economic Analysis as subject to the same economic shocks as the areas where minimum wages have increased. The resulting estimates point to job loss for the least-skilled workers studied, as do a number of other recent studies that address the Dube et al. criticisms.

The piece is a good brief survey of some of the developments since Card and Krueger. Here are some alternate links to the piece.

How out of bounds is the $15 California minimum wage?

By 2022, when fully phased in (small firms with fewer than 25 workers would have until 2023 to comply), the California minimum wage would represent 69 percent of the median hourly wage in the state, assuming 2.2 percent annual growth from the current median of roughly $19 per hour.

That 69 percent ratio would be all but unprecedented, in U.S. terms and internationally. The current California minimum wage represents about half the state’s median hourly wage, just as the federal minimum wage averaged 48 percent of the national median between 1960 and 1979, according to a 2014 Brookings Institution paper by economist Arindrajit Dube. (It is currently 38 percent of the national median.)

Other industrial democracies with statutory minimum wages typically set theirs at half the national median wage, too.

That is from Charles Lane. This is also worth noting:

Dube, generally a supporter of minimum wages, recommended that states use 50 percent of the median as their benchmark in the United States. (He told me by email that California’s experiment is worth running and monitoring.)

Yet Alan Krueger, among many others, is against it. On what grounds is it worth running?

The minimum wage and the Great Recession

I believe Card and Krueger will and should win Nobel Prizes, but their work is also not the last word on the minimum wage, especially during weak labor markets. Here is the most recent study, by Jeffrey Clemens:

I analyze recent federal minimum wage increases using the Current Population Survey. The relevant minimum wage increases were differentially binding across states, generating natural comparison groups. I first estimate a standard difference-in-differences model on samples restricted to relatively low-skilled individuals, as described by their ages and education levels. I also employ a triple-difference framework that utilizes continuous variation in the minimum wage’s bite across skill groups. In both frameworks, estimates are robust to adopting a range of alternative strategies, including matching on the size of states’ housing declines, to account for variation in the Great Recession’s severity across states. My baseline estimate is that this period’s full set of minimum wage increases reduced employment among individuals ages 16 to 30 with less than a high school education by 5.6 percentage points. This estimate accounts for 43 percent of the sustained, 13 percentage point decline in this skill group’s employment rate and a 0.49 percentage point decline in employment across the full population ages 16 to 64.

Do any of you see an ungated version? In any case I hope this receives the media attention it deserves. Will it?

New results on the minimum wage and inequality

There is a new paper in American Economic Journal: Applied Economics by David H. Autor, Alan Manning, and Christopher L. Smith, here is the abstract:

We reassess the effect of minimum wages on US earnings inequality using additional decades of data and an IV strategy that addresses potential biases in prior work. We find that the minimum wage reduces inequality in the lower tail of the wage distribution, though by substantially less than previous estimates, suggesting that rising lower tail inequality after 1980 primarily reflects underlying wage structure changes rather than an unmasking of latent inequality. These wage effects extend to percentiles where the minimum is nominally nonbinding, implying spillovers. We are unable to reject that these spillovers are due to reporting artifacts, however.

Here are earlier, ungated versions of the paper. Overall my read of this is that many people are leaping in too quickly and making unsupported claims about how the minimum wage is connected to income inequality.

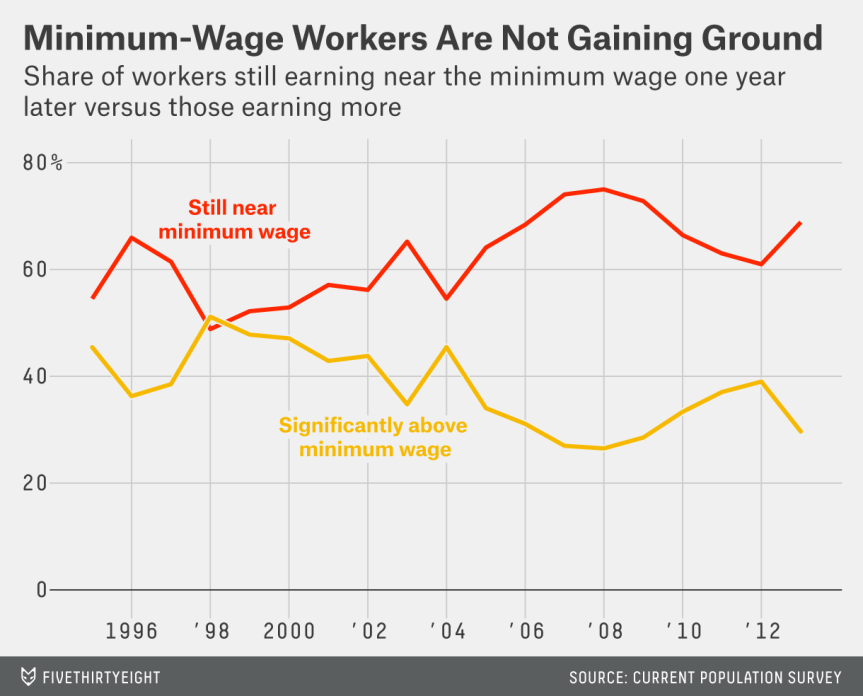

Is it getting harder to move beyond minimum wage jobs?

Ben Casselman has a good piece on this question, here is one excerpt:

During the strong labor market of the mid-1990s, only 1 in 5 minimum-wage workers was still earning minimum wage a year later. Today, that number is nearly 1 in 3, according to my analysis of government survey data. There has been a similar rise in the number of people staying in minimum-wage jobs for three years or longer…

Even those who do get a raise often don’t get much of one: Two-thirds of minimum-wage workers in 2013 were still earning within 10 percent of the minimum wage a year later, up from about half in the 1990s. And two-fifths of Americans earning the minimum wage in 2008 were still in near-minimum-wage jobs five years later, despite the economy steadily improving during much of that time.

The piece is of interest throughout.

What should be the minimum wage for rural Idaho?

There is a new opinion of sorts:

The Democratic Party platform now calls for a $15 per hour national minimum wage for all hourly workers after delegates voted in an amendment proposed by progressive activists during the Democratic National Committee Meeting here on Friday.

The pointer is from Conor Sen.

The minimum wage, the great reset, and the research of Isaac Sorkin

From Free Exchange at The Economist:

In the first [paper] Isaac Sorkin of the University of Michigan argues that firms may well substitute machines for people in response to minimum wages, but slowly. Mr Sorkin offers the example of sock-makers in the 1930s, which took years to switch to less labour-intensive machines after the federal minimum wage was brought in. He also explains how this finding squares with other research. Most studies look at past minimum wage increases that were not inflation-proofed. Firms may decide not to go through the hassle of investing in labour-saving machines if the minimum wage will affect them less over time. But they could respond differently to a more permanent increase.

Mr Sorkin crunches the numbers, using a model of the American restaurant industry in which companies choose between employees and machines. He investigates the effect of a permanent (ie, inflation-linked) increase in the minimum wage and shows that the tiny short-run effects on employment normally seen are fully consistent with a long-run response over 100 times larger. The lack of evidence for a big impact on employment in the short term does not rule out a much larger long-term effect.

In a second paper, written with Daniel Aaronson of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and Eric French of University College London, Mr Sorkin goes further, offering empirical evidence that higher minimum wages nudge firms away from people and towards machines. The authors look at the type of restaurants that close down and start up after a minimum-wage rise. An increase in the minimum wage seems to push some restaurants out of business. The eateries that replace them are more likely to be chains, which are more reliant on machines (and therefore offer fewer jobs) than the independent outlets they replace. This effect has not been picked up before because the restaurants which continue to operate do not change their employment levels, so the jobs total does not shift much in the short run.

The piece offers further points of interest.

The University of California raises its minimum wage

University of California President Janet Napolitano announced Wednesday the school will become the first to raise the on-campus minimum wage to $15 an hour.

“This is the right thing to do,” Napolitano said at a meeting in San Francisco. “For our workers and their families, for our mission and values, and to enhance UC’s leadership role by becoming the first public university in the United States to voluntarily establish a minimum wage of 15 dollars.”

The raise will benefit college employees who work more than 20 hours a week. It will also be applied to thousands of contractors working with the school.

U.S. minimum wage fact of the day

In Arkansas, the median hourly wage is $14.01. In Mississippi, it’s an astoundingly low $13.76. It’s likewise below $15 in six other states, and three U.S. territories.

That is from Catherine Rampell. In such situations, a $15 an hour minimum wage is…shall we say…risky?

How effective is the minimum wage at supporting the poor?

The highly esteemed and extremely proficient Thomas MaCurdy has a new piece in the JPE (jstor) on exactly that question. The news does not surprise me:

This study investigated the antipoverty efficacy of minimum wage policies. Proponents of these policies contend that employment impacts are negligible and suggest that consumers pay for higher labor costs through imperceptible increases in goods prices. Adopting this empirical scenario, the analysis demonstrates that an increase in the national minimum wage produces a value-added tax effect on consumer prices that is more regressive than a typical state sales tax and allocates benefits as higher earnings nearly evenly across the income distribution. These income-transfer outcomes sharply contradict portraying an increase in the minimum wage as an antipoverty initiative.

MaCurdy also writes:

About 35 percent of the total increase in after-tax benefits goes to families with income less than two times the poverty threshold, a common definition of the working poor or near-poor; nearly 13 percent goes to families principally supported by low-wage workers defined as earning wages at or below 117 percent…of the new 1996 minimum wage; and only about 14 percent goes to families with children on welfare.

Unlike most public income support programs, increased earnings from the minimum wage are taxable. Over 25 percent of the increased earnings are collected back as income and payroll taxes…Even after taxes, 27.6 percent of increased earnings go to families in the top 40 percent of the income distribution.

File under “Scream it From the Rooftops!” I do not see an ungated copy, but here is an earlier 2000 paper (pdf) by MaCurdy, with O’Brien-Strain, with broadly similar conclusions.

From that same JPE issue, cream skimming effects seem to be pretty small when it comes to school choice.

Minimum wage hikes and real net wages

…past experience has confirmed the nonmonetary impact of a minimum-wage hike on workers, not only in reduced fringe benefits but in increased work demands and decreased job training. For example:

- When the minimum wage was increased in 1967, economist Masanori Hashimoto found that workers gained 32 cents in money income but lost 41 cents per hour in training — a net loss of 9 cents an hour in full-income compensation.

- Similarly, Linda Leighton and Jacob Mincer in one study, and Belton Fleisher in another, concluded that increases in the minimum wage reduce on-the-job training and, as a result, dampen long-run growth in the real incomes of covered workers.

- Additionally, North Carolina State University economist Walter Wessels determined that a wage increase caused New York retailers to increase work demands. In most stores, fewer workers were given fewer hours to do the same work as before.

- More recently, Mindy Marks found that the $0.90 per hour increase in the federal minimum-wage rate in 1990 reduced the probability of workers receiving employer-provided health insurance from 66.2 percent to 63.1 percent, and increased the likelihood that covered workers would be reduced to part-time work by 26 percent.

Wessels also found that for every 10 percent increase in the minimum wage, workers lose 2 percent of nonmonetary compensation per hour. Extrapolating from Wessels’ estimates, an increase in the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to only $9.00 an hour would make covered workers worse off by 35 cents an hour.

And if the minimum wage were raised to $10.10 an hour, for example, the estimated 16.5 million workers earning between $7.25 and $10.10 could lose nonmonetary compensation more valuable than the $31 billion in additional wages they are expected to receive.

I would be skeptical or agnostic about some of those particular estimates, but surely the general point holds, and is hardly ever mentioned by advocates of hiking the minimum wage.

Will raising the minimum wage boost crime?

There is a recent 2013 paper on this topic by Andrew Beauchamp and Stacey Chan, the abstract is here:

Does crime respond to changes in the minimum wage? A growing body of empirical evidence indicates that increases in the minimum wage have a displacement effect on low-skilled workers. Economic reasoning provides the possibility that disemployment may cause youth to substitute from legal work to crime. However, there is also the countervailing effect of a higher wage raising the opportunity cost of crime for those who remain employed. We use the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 cohort to measure the effect of increases in the minimum wage on self-reported criminal activity and examine employment–crime substitution. Exploiting changes in state and federal minimum wage laws from 1997 to 2010, we find that workers who are affected by a change in the minimum wage are more likely to commit crime, become idle, and lose employment. Individuals experiencing a binding minimum wage change were more likely to commit crime and work only part time. Analyzing heterogeneity shows those with past criminal connections are especially likely to see decreased employment and increased crime following a policy change, suggesting that reduced employment effects dominate any wage effects. The findings have implications for policy regarding both the low-wage labor market and efforts to deter criminal activity.

For the pointer I thank Kevin Lewis. And there is an ungated version here (pdf). And via Gordon, here is a profile behind one of the forces behind the campaign to raise the minimum wage. Here is a good recent article on minimum wages and cross-state mobility.

The CBO report on the minimum wage

Spin it as you wish, we should not have a major party promoting, as a centerpiece initiative and for perceived electoral gain, a law that might put half a million vulnerable people out of work, and that during a slow labor market.

And the American people will never understand the ins and outs of the monopsony debate and the like. Overall, what kind of useful lesson is being taught here about the determinants of wages and prosperity?

I’m sorry people, but those are the bottom lines on this one.

Are recessions a good time to boost the minimum wage?

One empirical regularity is that many minimum wage boosts come during recessions or downturns, as many of you pointed out here. Yet I take this repeated pattern to be an argument for having a low, zero, or quite “fettered” minimum wage.

Let’s think through the economics. One of the main pro-minimum wage arguments — arguably the #1 argument — cites labor market monopsony. Let’s say you have a monopsonistic employer who holds back on bidding for more labor, out of fear that hiring more labor raises the price paid on all labor units of a certain quality (by assumption, there is no perfect price discrimination here). The minimum wage can get you out of this trap. By forcing the higher wage on all workers in any case, the employer now doesn’t hesitate to hire more of them because the “fear of bidding up the price of labor” effect is gone or diminished. And that is how, in some situations, a higher minimum wage can boost employment.

Now let’s say the economy is in a demand-driven downturn, which creates a surplus in the labor market. Now, to get more workers, the monopsonist firm does not have to raise the wage and it can get more workers at the prevailing wage. But employers just don’t want more workers, because of demand-side constraints. So employers could in fact hire more workers without pushing up wage rates at all, once again that is for all units of labor of a particular quality. Yes there is still monopsony, but the potential wage effects of hiring more labor are muted by the labor surplus. And that means boosting the minimum wage won’t create the beneficial hiring effects which operate in the more traditional monopsony scenario, explained in the paragraph directly above.

In other words, if you think we are now seeing a slow labor market for demand-side reasons, you should be skeptical of the monopsony argument for minimum wage hikes, at least for the time being.

By the way, demand-side problems often wreck the notion that the EITC and minimum wage are complements.

The bottom line is that a lot of the arguments for a higher minimum wage are inconsistent with or in tension with a demand-driven labor market slowdown. And I don’t exactly see the world rushing to point this out.

Here is my earlier argument that slow labor markets are the worst times to boost minimum wages. Here is my earlier post drawing a parallel between minimum wages (government-enforced sticky wages) and privately-enforced sticky wages. Here is an excerpt from that post:

I know many economists who will argue: “let’s raise the state-imposed minimum wage. Employers will respond by creating higher-productivity jobs, or by paying more, and few jobs will be lost.” I do not know many Keynesians who will argue: “In light of the worker-imposed minimum wage, employers will respond by creating higher-productivity jobs, or by paying more, and few jobs will be lost.”

Addendum: By the way, here are some graphs and regressions about the minimum wage and recessions, from Kevin Erdmann. I think he is attempting the impossible, but you still might find it instructive to look at some of the pictures.

Neumark and Wascher on minimum wages and youth unemployment

Here is the abstract from their piece from 2003 (pdf):

We estimate the employment effects of changes in national minimum wages using a pooled cross-section time-series data set comprising 17 OECD countries for the period 1975-2000, focusing on the impact of cross-country differences in minimum wage systems and in other labor market institutions and policies that may either offset or amplify the effects of minimum wages. The average minimum wage effects we estimate using this sample are consistent with the view that minimum wages cause employment losses among youths. However, the evidence also suggests that the employment effects of minimum wages vary considerably across countries. In particular, disemployment effects of minimum wages appear to be smaller in countries that have subminimum wage provisions for youths. Regarding other labor market policies and institutions, we find that more restrictive labor standards and higher union coverage strengthen the disemployment effects of minimum wages, while employment protection laws and active labor market policies designed to bring unemployed individuals into the work force help to offset these effects. Overall, the disemployment effects of minimum wages are strongest in the countries with the least regulated labor markets.