Results for “antibiotic” 59 found

Sunday assorted links

1. Is the last known antibiotic beginning to fail? (speculative)

3. Austan Goolsbee is blogging again, this time on the Bernie Sanders budget. And Kling on Summers.

*Foolproof: Why Safety Can Be Dangerous and How Danger Makes Us Safe*

That is the new and excellent book by Greg Ip, no fluff here substance all around. From the book’s home page:

How the very things we create to protect ourselves, like money market funds or anti-lock brakes, end up being the biggest threats to our safety and wellbeing.

Here is one excerpt:

The experiment found that people with no impairment to the brain’s emotional center were much more conservative. After losing money on one coin toss, only 40 percent of them agreed to invest on the next — but 85 percent of the brain-damaged patients did. By the end of the game, the brain-damaged patients had earned an average of $25.70 while the healthy players averaged $22.60.

And another:

By Spellberg’s reckoning, the odds of an adverse reaction to an antibiotic, such as an allergic reaction, are about 1 in 10, whereas the odds that someone will suffer because antibiotics were wrongly withheld are about 1 in 10,000. Nonetheless, most physicians do not want to run the risk of letting a patient suffer when an antibiotic could help…His research in Nepal produced the depressing finding that antibiotic resistance was highest in communities with the most doctors.

Spellberg thinks trying to persuade doctors not to prescribe antibiotics is a doomed strategy. Better, he says, to develop tests that rapidly identify what bug a patient has and thus whether an antibiotic is needed.

Strongly recommended, devoured my copy in a single sitting right away, due out this coming Tuesday. By the way here is the FT review by Andrew Hill.

Generic Drug Regulation and Pharmaceutical Price-Jacking

The drug Daraprim was increased in price from $13.60 to $750 creating social outrage. I’ve been busy but a few points are worth mentioning. The drug is not under patent so this isn’t a case of IP protectionism. The story as I read it is that Martin Shkreli, the controversial CEO of Turing pharmaceuticals, noticed that there was only one producer of Daraprim in the United States and, knowing that it’s costly to obtain even an abbreviated FDA approval to sell a generic drug, saw that he could greatly increase the price.

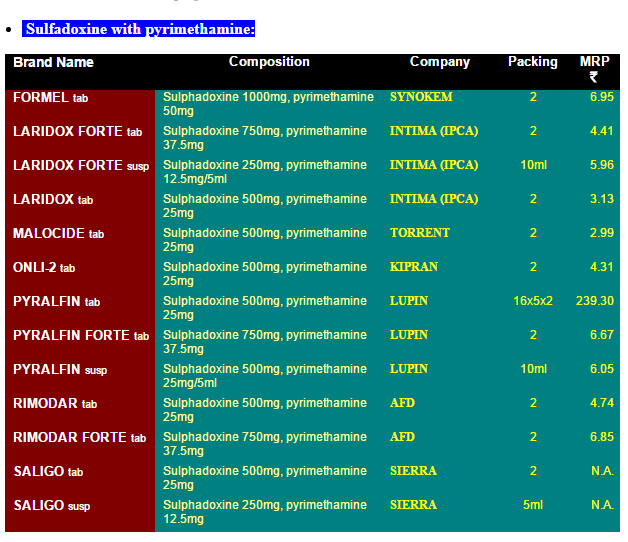

It’s easy to see that this issue is almost entirely about the difficulty of obtaining generic drug approval in the United States because there are many suppliers in India and prices are incredibly cheap. The prices in this list are in India rupees. 7 rupees is about 10 cents so the list is telling us that a single pill costs about 5 cents in India compared to $750 in the United States!

It is true that there are real issues with the quality of Indian generics. But Pyrimethamine is also widely available in Europe. I’ve long argued for reciprocity, if a drug is approved in Europe it ought to be approved here. In this case, the logic is absurdly strong. The drug is already approved here! All that we would be doing is allowing import of any generic approved as such in Europe to be sold in the United States.

Note that this is not a case of reimportation of a patented pharmaceutical for which there are real questions about the effect on innovation.

Allowing importation of any generic approved for sale in Europe would also solve the issue of so-called closed distribution.

There is no reason why the United States cannot have as vigorous a market in generic pharmaceuticals as does India.

Hat tip: Gordon Hanson.

Assorted links

1. Scott Sumner on Keynesian excuses.

2. Alan Krueger working for Uber. And dating average is over. And rendering Tyler Cowen obsolete.

3. Newspapers are still deep in a financial hole.

4. Divorce machine gun markets in everything. And Croatia wants to peg to the Swiss franc (!) for mortgage protection.

5. Department of Uh-Oh: more competition leads to higher antibiotic prescription rates.

6. Matthew Slaughter is now Dean of Dartmouth business school.

7. The legal system that is German. They got the ruling right, I say.

8. Paul Krugman’s estimate: “So, Draghi’s big announcement seems to have raised expected European inflation by one-fifth of a percentage point.” Alternatively, Daniel Davies on why QE might prove effective.

Is the Great Stagnation soon over?

The method, which extracts drugs from bacteria that live in dirt, has yielded a powerful new antibiotic, researchers reported in the journal Nature on Wednesday. The new drug, teixobactin, was tested in mice and easily cured severe infections, with no side effects.

Better still, the researchers said, the drug works in a way that makes it very unlikely that bacteria will become resistant to it. And the method developed to produce the drug has the potential to unlock a trove of natural compounds to fight infections and cancer — molecules that were previously beyond scientists’ reach because the microbes that produce them could not be grown in the laboratory.

Studies on people will start in about two years, the NYT article is here. Here is the underlying Nature article.

Alternatively, here is a claim that James Harden is the future of basketball.

I thank numerous MR readers for related pointers.

Vegetable Eggs

Technology Review: Hampton Creek’s CEO, Josh Tetrick, wants to do to the $60 billion egg industry what Apple did to the CD business. “If we were starting from scratch, would we get eggs from birds crammed into cages so small they can’t flap their wings, shitting all over each other, eating antibiotic-laden soy and corn to get them to lay 283 eggs per year?” asks the strapping former West Virginia University linebacker. While an egg farm uses large amounts of water and burns 39 calories of energy for every calorie of food produced, Tetrick says he can make plant-based versions on a fraction of the water and only two calories of energy per calorie of food — free of cholesterol, saturated fat, allergens, avian flu, and cruelty to animals. For half the price of an egg.

At present, Hampton Creek is focusing on finding vegetable proteins than can substitute for eggs in cakes, salad dressings, mayo and so forth rather than replacing the over-easy at the diner. As with in-vitro meat, however, vegetable eggs pursued for economic reasons will end up greatly supporting the 21st movement for vegetarianism.

Don’t put your money where your mouth is

Not a surprise to me but yikes nonetheless:

In the first comprehensive study of the DNA on dollar bills, researchers at New York University’s Dirty Money Project found that currency is a medium of exchange for hundreds of different kinds of bacteria as bank notes pass from hand to hand.

By analyzing genetic material on $1 bills, the NYU researchers identified 3,000 types of bacteria in all—many times more than in previous studies that examined samples under a microscope. Even so, they could identify only about 20% of the non-human DNA they found because so many microorganisms haven’t yet been cataloged in genetic data banks.

Easily the most abundant species they found is one that causes acne. Others were linked to gastric ulcers, pneumonia, food poisoning and staph infections, the scientists said. Some carried genes responsible for antibiotic resistance.

“It was quite amazing to us,” said Jane Carlton, director of genome sequencing at NYU’s Center for Genomics and Systems Biology where the university-funded work was performed. “We actually found that microbes grow on money.”

This was, by the way, a relatively frequent complaint in 19th century monetary writings, with the advent of banknotes.

Assorted links

1. Eurozone industrial production: the recovery?

2. Are Chinese provinces picking up the stimulus slack?

3. Yuval Levin has a good analysis of the sequester redo.

4. Fama and Shiller, on each other.

5. Average is Over in farming. And the FDA restricts antibiotic use in livestock.

Assorted quotations

1. “Only a few authors have bothered to approach the disintegration of America in an innovative way.”

2. “They estimated that without antibiotics, one out of every six recipients of new hip joints would die.”

3. “The urban refugees come from all walks of life — businesspeople and artists, teachers and chefs — though there is no reliable estimate of their numbers. They have staked out greener lives in small enclaves, from central Anhui Province to remote Tibet. Many are Chinese bobos, or bourgeois bohemians, and they say that besides escaping pollution and filth, they want to be unshackled from the material drives of the cities — what Ms. Lin derided as a focus on “what you’re wearing, where you’re eating, comparing yourself with others.” The link is here.

4. “It is the first time that the West has lost a soft power contest with Russia.”

5. “I do take painting seriously,” he said. “It’s changed my life.”

Should there be required labeling of GMOs?

Here is one on-the-mark take (of many):

…there have been more than 300 independent medical studies on the health and safety of genetically modified foods. The World Health Organization, the National Academy of Sciences, the American Medical Association and many others have reached the same determination that foods made using GM ingredients are safe, and in fact are substantially equivalent to conventional alternatives. As a result, the FDA does not require labels on foods with genetically modified ingredients because it acknowledges they may mislead consumers into thinking there could be adverse health effects, which has no basis in scientific evidence.

Or try the National Academy of Sciences from 2010:

Many U.S. farmers who grow genetically engineered (GE) crops are realizing substantial economic and environmental benefits — such as lower production costs, fewer pest problems, reduced use of pesticides, and better yields — compared with conventional crops, says a new report from the National Research Council.

Here is a good NYT summary Op-Ed on that report. There is not the scientific evidence for Mark Bittman’s recent evaluation that:

G.M.O.’s, to date, have neither become a panacea — far from it — nor created Frankenfoods, though by most estimates the evidence is far more damning than it is supportive.

It’s the tag there that is problematic. He doesn’t offer a citation, nor has he in past columns offered convincing material to back this evaluation (you can read here for a somewhat more detailed account from Bittman; it simply minimizes benefits and does not support “by most estimates the evidence is far more damning than it is supportive”). This earlier critique of Bittman is on the mark on virtually every point.

The standards of evidence being applied here are extremely weak. In that last Bittman link he wrote that:

…The surge in suicides among Indian farmers has been attributed by some, at least in part, to G.E. crops…

The link is to a sensationalistic Daily Mail (tabloid) story, yet that gets translated into “has been attributed by some.” In that story, the suicides were caused by indebtedness and supposedly the debts were in part caused by a desire by farmers to buy GMO crops. In comparable terms one could write that anything one spends money on could cause suicide through the medium of indebtedness.

By the way, the Wikipedia treatment gives some more detailed citations suggesting that GMO crops are not a significant cause of farmer suicides in India. The most careful study of the matter reports this:

We first show that there is no evidence in available data of a “resurgence” of farmer suicides in India in the last five years. Second, we find that Bt cotton technology has been very effective overall in India. However, the context in which Bt cotton was introduced has generated disappointing results in some particular districts and seasons. Third, our analysis clearly shows that Bt cotton is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the occurrence of farmer suicides. In contrast, many other factors have likely played a prominent role.

I would in fact be more supportive of the GMO labeling idea if renowned food writers such as Bittman, and many others including left-wing economists, would come out and boldly proclaim the science about GMOs to their readers. Too often the tendency is to use a “I’ll try not to say anything literally incorrect, while insinuating there are big problems” method of scoring points against big agriculture. (Another common trope is to switch the discussion to “distribution” and to suggest, either explicitly or implicitly, that a net benefit technology such as GMOs is somehow unnecessary or undesirable; dare I utter the words “mood affiliation“?) GMO labeling is the one issue which has gained legal traction, so critics of “Big Ag” just can’t bring themselves to give it up.

Bittman’s whole column is about GMOs, but he gets at the important point only in his final sentence:

[With better information] We’d be able to make saner choices, and those choices would greatly affect Big Food’s ability to freely use genetically manipulated materials, an almost unlimited assortment of drugs and inhumane and environmentally destructive animal-production methods.

Overuse of antibiotics and animal treatment (both cruelty and environmental issues) — now those are two very real problems, backed by overwhelming scientific evidence. The fact that the California referendum is instead about GMOs — which have overwhelming scientific evidence for net benefit and minimal risks — is the real scandal.

It’s time that our most renowned food writers woke up to that difference. In the meantime, they are doing both us and themselves a deep disservice.

Assorted links

1. World’s first commercial 3-D chocolate printer, story here, beware noisy video at that link.

2. Cardboard arcade made by a nine-year-old boy, hat tip to Karina and Chad.

3. Tightening antibiotic use for livestock; let’s hope it works, a partial but not complete Coasian trade says it won’t, in a pinch farmers will buy vets. More here.

College has been oversold

Here, drawn from my new e-book, Launching the Innovation Renaissance (published by TED) is part of a section on college education. (See also the op-ed in IBD)

Educated people have higher wages and lower unemployment rates than the less educated so why are college students at Occupy Wall Street protests around the country demanding forgiveness for crushing student debt? The sluggish economy is tough on everyone but the students are also learning a hard lesson, going to college is not enough. You also have to study the right subjects. And American students are not studying the fields with the greatest economic potential.

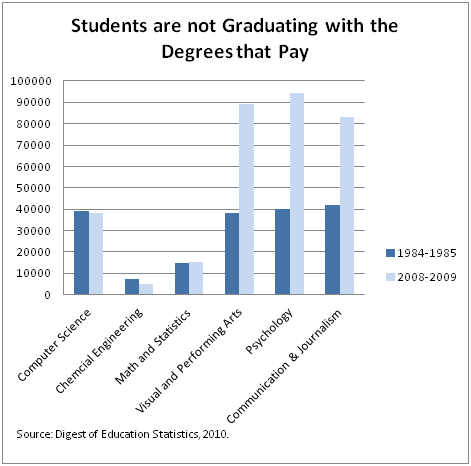

Over the past 25 years the total number of students in college has increased by about 50 percent. But the number of students graduating with degrees in science, technology, engineering and math (the so-called STEM fields) has remained more or less constant. Moreover, many of today’s STEM graduates are foreign born and are taking their knowledge and skills back to their native countries.

Consider computer technology. In 2009 the U.S. graduated 37,994 students with bachelor’s degrees in computer and information science. This is not bad, but we graduated more students with computer science degrees 25 years ago! The story is the same in other technology fields such as chemical engineering, math and statistics. Few fields have changed as much in recent years as microbiology, but in 2009 we graduated just 2,480 students with bachelor’s degrees in microbiology — about the same number as 25 years ago. Who will solve the problem of antibiotic resistance?

If students aren’t studying science, technology, engineering and math, what are they studying?

In 2009 the U.S. graduated 89,140 students in the visual and performing arts, more than in computer science, math and chemical engineering combined and more than double the number of visual and performing arts graduates in 1985.

The chart at right shows the number of bachelor’s degrees in various fields today and 25 years ago. STEM fields are flat (declining for natives) while the visual and performing arts, psychology, and communication and journalism (!) are way up.

There is nothing wrong with the arts, psychology and journalism, but graduates in these fields have lower wages and are less likely to find work in their fields than graduates in science and math. Moreover, more than half of all humanities graduates end up in jobs that don’t require college degrees and these graduates don’t get a big college bonus.

Most importantly, graduates in the arts, psychology and journalism are less likely to create the kinds of innovations that drive economic growth. Economic growth is not a magic totem to which all else must bow, but it is one of the main reasons we subsidize higher education.

The potential wage gains for college graduates go to the graduates — that’s reason enough for students to pursue a college education. We add subsidies to the mix, however, because we believe that education has positive spillover benefits that flow to society. One of the biggest of these benefits is the increase in innovation that highly educated workers theoretically bring to the economy.

As a result, an argument can be made for subsidizing students in fields with potentially large spillovers, such as microbiology, chemical engineering, nuclear physics and computer science. There is little justification for subsidizing sociology, dance and English majors.

College has been oversold. It has been oversold to students who end up dropping out or graduating with degrees that don’t help them very much in the job market. It also has been oversold to the taxpayers, who foot the bill for these subsidies.

Consumer surplus from the internet, revisited

David Henderson raised this question again, as has Bryan Caplan in the past. Both seem to suggest that the consumer surplus from the internet is quite high or perhaps even “huge,” although I am not sure what number they have in mind. I am disappointed that they are not engaging with the academic literature on this topic.

1. An 86-page 2010 FCC study concludes that “a representative household would be willing to pay about $59 per month for a less reliable Internet service with fast speed (“Basic”), about $85 for a reliable Internet service with fast speed and the priority feature (“Premium”), and about $98 for a reliable Internet service with fast speed plus all other activities (“Premium Plus”). An improvement to very fast speed adds about $3 per month to these estimates.”

2. A study from Japan found that: “The estimated WTP for availability of e-mail and web browsing delivered over personal computers are 2,709 Yen and 2,914 Yen, on a monthly basis, respectively, while average broadband access service costs approximately 4,000 Yen in Japan.” By the way, right now the exchange rate is about 80 Yen to a dollar.

3. The Austan Goolsbee paper, based on 2005 data, does a time study to find that the consumer surplus of the internet is about two percent of income.

4. This paper finds a four percent consumer surplus from the personal computer more generally, not just the internet.

5. Robin Hanson serves up an excellent debunking of some exaggerated consumer surplus claims.

6. Many of the benefits of internet cruising are captured in gdp figures, such as using it to find a job or the money you spend on smart phones. By the way, here is a good paper on consumer surplus in the book market, though it offers no overall CS estimate from the internet.

You can take issue with these papers for ignoring personal internet use at work, the inframarginal benefits to infovores, or other issues, such as whether the existence of the internet increases workloads in what are supposedly leisure hours. But there is the place to start and the numbers are not outrageously high, not close to it.

Or put all that aside and think through the problem intuitively, in terms of time use decisions. Your marginal hour of non-internet leisure time is worth more than spending another hour of time on the internet. In other words, at the margin your consumer surplus from the internet is about the same as your consumer surplus from going to the movies or taking a walk. That’s nice, but suddenly the consumer surplus from the internet doesn’t seem like such a big deal any more. It’s probably not going to add up to millions. If the internet were as awesome for consumer fun as some people claim, it would have pushed out more of our other uses of leisure time.

What about the inframarginal units of internet use? Might the consumer surplus there be huge? If you think of books, movies, newspapers, and CDs as some of the relatively close substitutes for some uses of the internet, we know from cultural economics that the demand curves for those enjoyments are usually smooth, normal, and continuous, more or less. They don’t have enormous, hidden inframarginal benefits.

Penicillin probably does have such an enormous inframarginal benefit; the initial doses can be of great value but past some margin the value falls to zero or negative. The internet doesn’t seem to be like penicillin.

You can even make an argument that the inframarginal valuations of internet use are especially low, relative to the marginal values. Have you ever heard that the internet is “addictive”? That doing some makes you want to do more? That the internet has a virtually unending supply of interesting content? Personally I find that I could read more working papers, without much decline in their interestingness, except that the exigencies of my daily life interfere (at some margin). Those are all signs that the marginal valuation of the internet does not fall off so drastically as one moves down the demand curve. If you’re not using the internet more, it’s not because the internet is getting much worse with additional use units, it’s because it is digging into increasingly important parts of your non-internet life. That brings us back to the inframarginal unit having a value not so far away from the marginal units.

It is likely that the consumer surplus of the internet is in the range of two to four percent of gdp. On one hand, that’s “a lot” but on the other hand it’s not enough to close the “stagnation gap” in wages since 1973. It’s not close. It also may be quite small compared to the consumer surplus from the major innovations from earlier in the 20th century, such as antibiotics, without which I probably would be dead.

Assorted links

Sentences to ponder

There’s a measles outbreak in Massachusetts, probably thanks to low vaccination rates.

It’s hard to believe, but we’re sliding backwards on two of the three public health achievements of the 20th century: vaccination, antibiotics, and clean water. Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem, one that we’re partly inflicting on ourselves by rampant overuse. And now vaccine resistance is spreading among parents who want to free ride on the herd immunity of others. If these diseases were widespread, they’d be rushing to vaccinate their kids. But they can delay, or forgo the vaccines entirely, thanks to other parents who are willing to risk their kids in order to do the right thing. They’re already killing little babies who catch pertussis before they can be vaccinated, and now measles has killed six people in France just since the start of the year.

That is from Megan McArdle.