Results for “more police” 437 found

We should do more to privatize bus systems

Local governments spend roughly $1.6 trillion per year to provide a variety of public services ranging from police and fire protection to public schools and public transit. However, we know little about public sector’s productivity in delivering key services. Public bus service represents a standardized output for benchmarking the cost of local government service provision. Among the top twenty largest cities, there exists significant dispersion in the operating cost per bus mile with the highest being more than three times as high as the lowest. Using a regression discontinuity design, we estimate the cost savings from privatization and explore the political economy of why privatization rates are lower in high cost unionized areas. Our analysis suggests that fully privatizing all bus transit would generate cost savings of approximately $5.7 billion, or 30% of total U.S. bus transit operating expenses. The corresponding increased use of public transit from this cost reduction would lead to a gain in social welfare of $524 million, at minimum, and at least 26,000 additional transit jobs.

That is from Rhiannon Jerch, Matthew E. Kahn, and Shanjun Li, forthcoming in the Journal of Public Economics.

Are U.S. Cities Underpoliced?

Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary have a forthcoming paper in the Review of Economics and Statistics that takes a new approach to estimate the effect of police on crime. If you run an ordinary regression using the number of police to explain the number of crimes you typically find small or even positive coefficients, i.e. the police appear to have no effect on crime or maybe even a positive effect. The usual explanation is endogeneity. The number of police influence the number of crimes but the number of crimes also influences the number of police. The recent literature has focused on breaking this endogeneity circle by finding a change in the number of police that is exogenous, i.e. random with respect to crime. My paper with Jon Klick, for example, uses random movements in the terror alert level combined with the fact that the police go on double shifts when the terror alert level rises to estimate the effect of police on crime in Washington, DC. If the assumption of exogeneity is satisfied then you have pulled a random experiment out of natural data, hence a natural experiment. Obviously, if the exogeneity assumption isn’t satisfied the technique doesn’t work. But even if the exogeneity assumption is satisfied there is another problem–by focusing only on changes in police and crime when the terror alert level changes you are throwing out most of the variation in the data so the estimates are going to be less precise than if you used more of the variation in the data.

Chalfin and McCrary acknowledge the endogeneity problem but they suggest that a more important reason why ordinary regression gives you poor results is that the number of police is poorly measured. Suppose the number of police jumps up and down in the data even when the true number stays constant. Fake variation obviously can’t influence real crime so when your regression “sees” a lot of (fake) variation in police which is not associated with variation in crime it’s naturally going to conclude that the effect of police on crime is small, i.e. attenuation bias.

By comparing two different measures of the number of police, Chalfin and McCrary show that a surprising amount of the ups and downs in the number of police is measurement error. Using their two measures, however, Chalfin and McCrary produce a third measure which is better than either alone. Using this cleaned-up estimate, they find that ordinary regression (with controls) gives you estimates of the effect of police on crime which are plausible and similar to those found using other techniques like natural experiments. Chalfin and McCrary’s estimates, however, are more precise since they use much more of the variation in the data.

Using these new estimates of the effect of police and crime along with estimates of the social cost of crime they conclude (as I have argued before) that U.S. cities are substantially under-policed.

Hat tip Kevin Lewis.

Addendum: After writing this post I discovered that I had covered the Chalfin and McCrary paper when it was a working paper, five years ago! This tells you something about how long it can take to get an economics paper published.

Baltimore Tipped

Last year I wrote, In Baltimore Arrests are Down and Crime is Way Up. I worried that a crime wave occasioned in part by a work stoppage could tip into a much higher level of crime:

With luck, the crime wave will subside quickly, but the longer-term fear is that the increase in crime could push arrest and clearance rates down so far that the increase in crime becomes self-fulfilling. The higher crime rate itself generates the lower punishment that supports the higher crime rate…

In the presence of multiple equilibria, it’s possible that a temporary shift could push Baltimore into a permanently higher high-crime equilibrium. Once the high-crime equilibrium is entered, it may be very difficult to exit without a lot of resources that Baltimore doesn’t have.

Writing at FEE, Daniel Bier takes a long look at crime in Baltimore and the history of problems which got us to this point. He notes that the sharp drop in arrests which I discussed was indeed temporary.

But unfortunately:

Tabarrok’s fear that “a temporary shift could push Baltimore into a permanently higher high-crime equilibrium” looks to be borne out. Crime shot up due to temporary factors, but once those factors receded, the police [have] been unable to cope with the new status quo. Baltimore’s vicious crime cycle remains stuck in high gear.

…With 178 killings already in 2016, Baltimore is on track for 294 murders this year — shy of last year’s total of 344 homicides, but well above 2014’s total of 211.

To quote HBO’s The Wire, if Baltimore had New York’s population, it would be clocking nearly four thousand murders a year.

Daniel argues that Baltimore does have the resources to get back on track but at this stage in the game it may not have the will.

In one important respect, Baltimore is worse off than Ferguson, MO. Ferguson had poor policing but an average crime rate. Baltimore has poor policing and a sky high crime rate. Baltimore desperately needs more policing but the police have lost the trust of a vital part of the community and as the Department of Justice’s report on Baltimore brutally illustrates, in some cases rightly so. The DOJ report might provide the impetus for a surge–a large but temporary influx of federal funds for new hiring under a new police administration–that could reestablish a decent equilibrium and reform the department at the same time. Many, however, will decry a federal “takeover” of policing. Ironically, the law and order candidate might be more likely to impose Federal control, albeit it would be less likely to work.

Baltimore is truly stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Do we need *more* radical Islam?

Here is the latest report:

The man behind the Nice truck attack drank alcohol, beat his wife and has been described as “not a Muslim but a shit”.

Furthermore about a third of the dead from the attack were Muslims (NYT).

One form of radical Islam is Sufism, many strains of which are pacifist in nature. It was not too long ago that Amjad Sabri, of Sabri brothers fame, was shot dead in Pakistan by terrorists. Was he the radical or were they? And which do we want more of?

Recently I had a long lunch with a researcher in Brussels who was studying terrorism in the city. He was very much of the view that most of the terrorists and terrorist-candidates are not very religious, although most did end up latching onto Islam as an identity marker and source of group support.

In other words, they are not “radical Islam.” Here is a Vox piece on why the term “radical Islam” is not always productive.

In general, I am suspicious when someone dismisses a view for being “radical” or “extreme.” There is usually sloppy thinking behind that designation. Why not just say what is wrong with the view? How for instance are we supposed to feel about “radical Christianity”? Good or bad? Does it mean Origen or Ted Cruz or something altogether different? Can’t we just debate the question itself?

The same is true in politics. Let’s say someone favors free trade and the First Amendment. Is that “radical”? Or is it mainstream and thus non-radical? Does labeling it radical further the debate on whether or not those are the correct positions?

For similar reasons, don’t be too quick to call someone or someone’s views “divisive.” If the status quo is problematic, a good reform might be divisive in some critical regards. Arguably the modern world is specializing in “non-divisive” means of creating an ultimately divisive state of affairs.

More generally, when that term “radical” or “extreme” is introduced, there is a presupposition that no external argument or perspective can be so strong to counter what one’s own swarmy group takes for granted.

Police versus Prisons

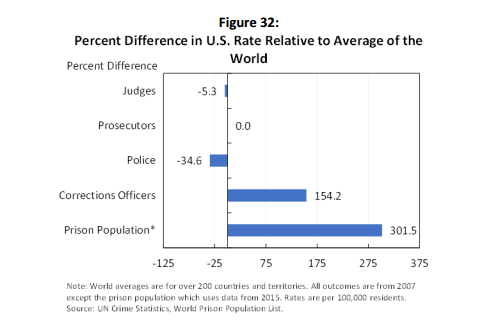

Here’s a remarkable graph from the Council of Economic Advisers report on incarceration and the criminal justice system. The graph shows that the United States employs many more prison guards per-capita than does the rest of the world. Given our prison population that isn’t surprising. What is surprising is that on a per-capita basis we employ 35% fewer police than the world average. That’s crazy.

Our focus on prisons over police may be crazy but it is consistent with what I called Gary Becker’s Greatest Mistake, the idea that an optimal punishment system combines a low probability of being punished with a harsh punishment if caught. That theory runs counter to what I have called the good parenting theory of punishment in which optimal punishments are quick, clear, and consistent and because of that, need not be harsh.

We need to change what it means to be “tough on crime.” Instead of longer sentences let’s make “tough on crime” mean increasing the probability of capture for those who commit crimes.

Increasing the number of police on the street, for example, would increase capture rates and deter crime and by doing so it would also reduce the prison population. Indeed, in a survey of crime and policing that Jon Klick and I wrote in 2010 we found that a cost-benefit analysis would justify doubling the number of police on the street. We based our calculation not only on our own research from Washington DC but also on the research of many other economists which together provide a remarkably consistent estimate that a 10% increase in policing would reduce crime by 3 to 5%. Using our estimates, as well as those of some more recent papers, the Council of Economic Advisers also estimates big benefits (somewhat larger than ours) from an increase in policing. Moreover, what the CEA makes clear is that a dollar spent on policing is more effective at reducing crime than a dollar spent on imprisoning.

Unfortunately, selling the public on more policing is likely to be difficult. Some of the communities most in need of more police are also communities with some of the worst policing problems. We aren’t likely to get more policing until people are convinced that we have better policing. Moreover, people are right to be skeptical because the type of policing that works is not simply boots on the ground. As the CEA report notes:

Model policing tactics are marked by trust, transparency, and collaborations between police and community stakeholders…

Better policing and more policing complement one another. Greater trust can come with body cameras as well as community oversight and other efforts to bring transparency and accountability. Most importantly, the drug war has eroded trust between police and community and that has led to an endogenous equilibrium in which some communities are rife with both drugs and crime. Fortunately, marijuana decriminalization and legalization have begun to move resources away from the war on drugs. Legalization in states like Colorado does not appear to have increased crime and has likely contributed to a dramatic decline of violence in Mexico. As we move resources away from drug crime, police will have more resources to raise the punishment rate for those traditional crimes like murder, robbery and rape that communities everywhere do want punished.

Addendum: See also Peter Orszag’s column on this issue.

Why can’t Europe police terrorism better?

What Europe does not have is any cross-national agency with the power to carry out its own investigation and make its own arrests.

This means that cross-border policing in the European Union has big holes. It depends heavily on informal cooperation rather than formal institutions with independent authority. Sometimes this works reasonably well. Sometimes this works particularly badly. Belgium is a notorious problem case, because its policing arrangements are heavily localized. In the past, many Belgian policing forces have had difficulty cooperating with each other, let alone with other European forces.

That is from Henry Farrell, there are other points at the link. Here is one bit more:

To take a different example, immigration and refugees present an even bigger and more visible set of challenges to the E.U. than terrorism, yet the E.U. has been unable to agree on reforms that might expand the budget and powers of FRONTEX, the E.U. agency charged with coordinating border control. Creating a European FBI-style institution would be an even bigger lift.

Keep this in mind the next time you are tempted to believe that the EU is doing everything possible to manage the refugees crisis well.

In Baltimore Arrests are Down and Crime is Way Up

A debate forum at the New York Times begins:

A rise in gun violence in New York, Baltimore and other cities after months of angry protests over police killings of unarmed black men, have led some to see a ”Ferguson effect,” in which police, spooked by criticism of aggressive tactics, have pulled back, making fewer arrests and fewer searches for weapons.

But has a wave of murders and shootings brought an end to the long drop in crime?

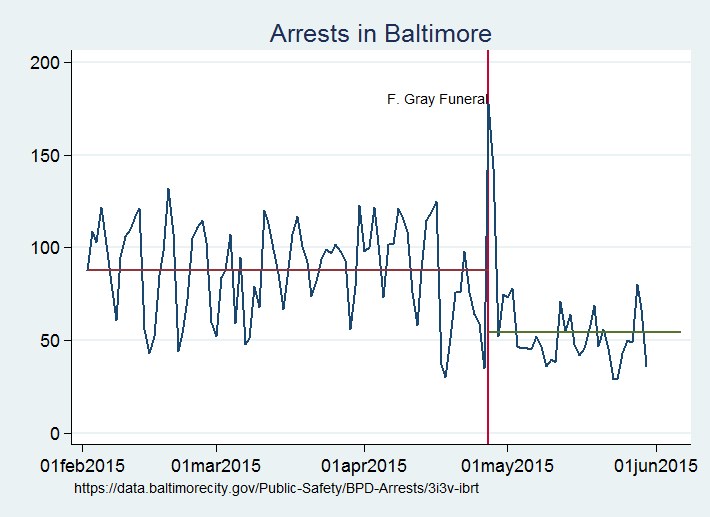

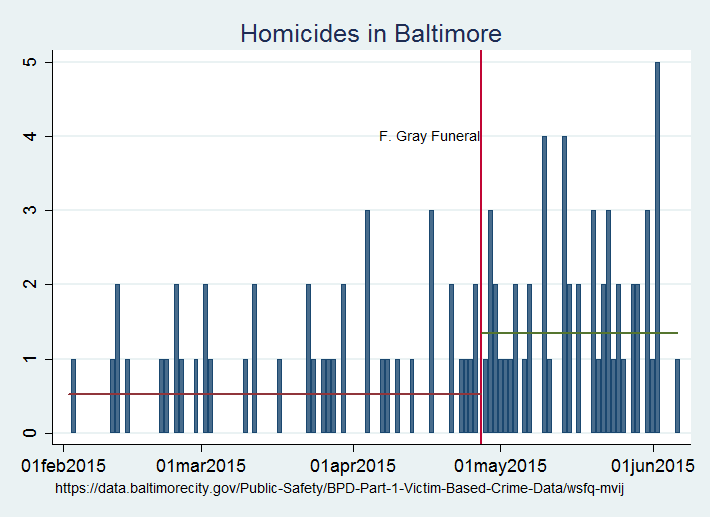

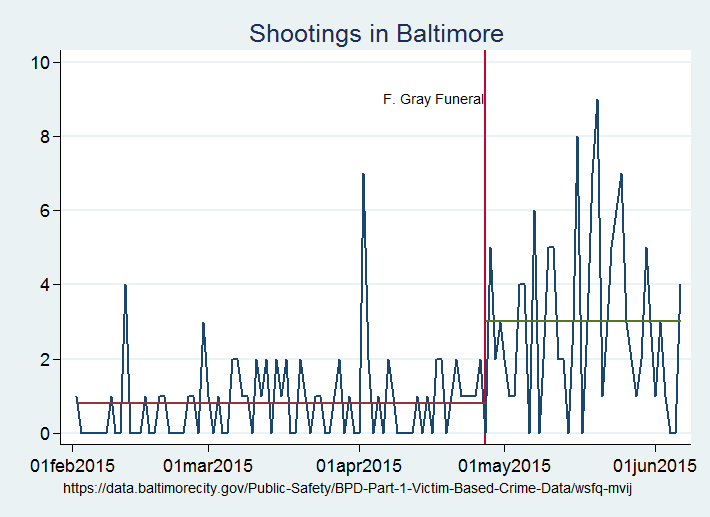

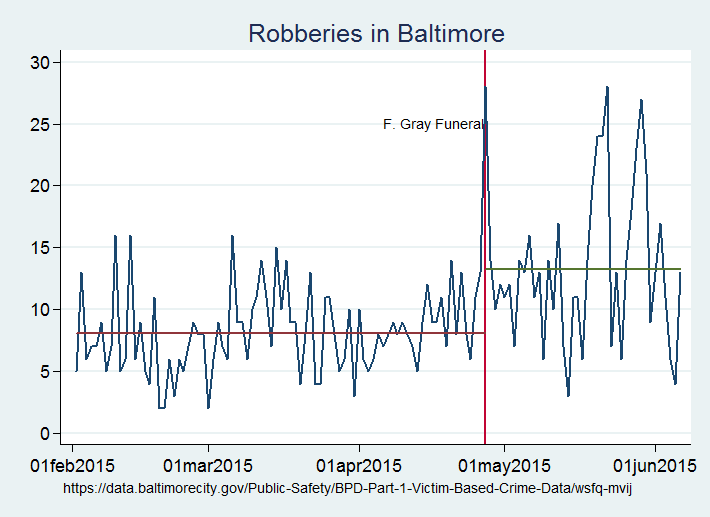

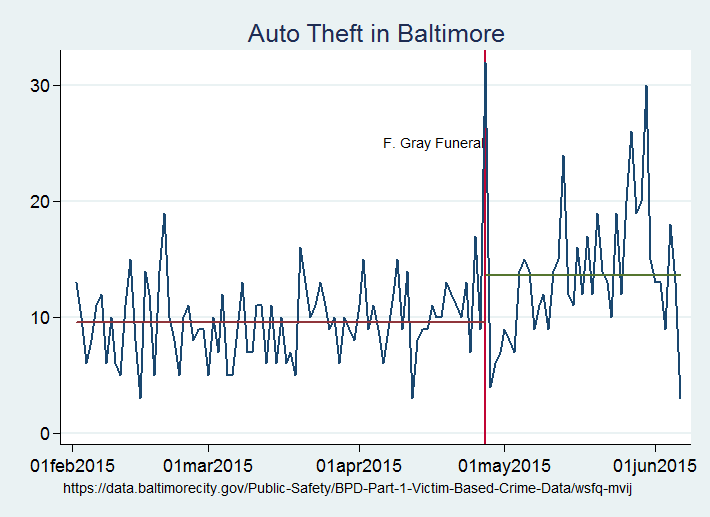

I don’t think that we will see a sustained increase in crime at the national level. But there is no question that we are seeing a Ferguson effect in Baltimore–more precisely a Freddie Gray effect. Arrests in Baltimore have fallen by nearly 40% since Freddie Gray’s funeral and the start of the riots on April 27. In the approximately 3 months before the Gray funeral police made an average of 87.7 arrests per day, since that time they have made only 54.6 arrests a day on average (up to May 30, most recent data).

As Peter Moskos argues:

In Baltimore today, several police officers need to respond to situations where formerly one could do the job. This stretches resources and prevents proactive policing.

Not all arrests are good arrests, of course, but the strain is cutting policing across the board and the criminals are responding to incentives. Fewer police mean more crime. As arrests have fallen, homicides, shootings, robberies and auto thefts have all spiked upwards. Homicides, for example, have more than doubled from .53 a day on average before the unrest to 1.35 a day after (up to June 6, most recent data)–this is an unprecedented increase–and the highest homicide rate Baltimore has ever seen.

Put differently, the unrest in Baltimore and subsequent reduction in policing is responsible for roughly twenty “excess” deaths. (so far)

It’s not just homicides, the number of shootings in Baltimore has more than tripled. Shootings increased from .82 a day before the unrest to just over 3 a day. Since the onset of the riots there has hardly been a day without a shooting.

Robberies are up from 8.1 per day to 13.25 per day on average.

Even auto thefts are up from 9.6 per day to 13.6 per day on average.

The increase in homicides and other crime is terrible and it is also putting a strain on police resources.

Police Commissioner Anthony W. Batts said the rise in killings is “backlogging” investigators, just as the community has become less engaged with police, providing fewer tips.

With luck the crime wave will subside quickly but the longer-term fear is that the increase in crime could push arrest and clearance rates down so far that the increase in crime becomes self-fulfilling. The higher crime rate itself generates the lower punishment that supports the higher crime rate (see my theory paper). In the presence of multiple equilibria it’s possible that a temporary shift could push Baltimore into a permanently higher high-crime equilibrium. Once the high-crime equilibrium is entered it may be very difficult to exit without a lot of resources that Baltimore doesn’t have. I have long argued that high-crime areas need more police but the tragedy is that they also need high-quality policing and that too is made more difficult to achieve by strained budgets and strained police.

HIPAA, the Police, and Goffman’s On the Run

Some people are calling Steven Lubet’s new review of Alice Goffman’s On the Run “troubling” and even “devastating” but I am non-plussed. Lubet questions the plausibility of some of Goffman’s accounts:

She describes in great detail the arrest at a Philadelphia hospital of one of the 6th Street Boys who was there with his girlfriend for the birth of their child. In horror, Goffman watched as two police officers entered the room to place the young man in handcuffs, while the new mother screamed and cried, “Please don’t take him away. Please, I’ll take him down there myself tomorrow, I swear – just let him stay with me tonight.” (p. 34). The officers were unmoved; they arrested not only Goffman’s friend, but also two other new fathers who were caught in their sweep.

How did the policemen know to look for fugitives on the maternity floor? Goffman explains:

According to the officers I interviewed, it is standard practice in the hospitals serving the Black community for police to run the names of visitors or patients while they are waiting around, and to take into custody those with warrants . . . .

The officers told me they had come into the hospital with a shooting victim who was in custody, and as was their custom, they ran the names of the men on the visitors’ list.

This account raises many questions. Even if police officers had the time and patience to run the names of every patient and visitor in a hospital, it would violate the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) for the hospital simply to provide an across-the-board list….

In addition, Lubet contacted a source in the Philadelphia police department and asked if there was any such policy.

When I asked if her account was possible, he said, “No way. There was never any such policy or standard practice.” In addition, he told me that all of the trauma centers in Philadelphia – where police are most likely to be “waiting around,” as Goffman put it, for prisoners or shooting victims – have always been extremely protective of their patient logs. He flatly dismissed the idea that such lists ever could have been available upon routine request as Goffman claims. “That’s outlandish,” he said.

It would also be outlandish for police to beat and kill people without cause but since Goffman’s book has appeared we have plenty of video evidence that the type of actions she claims to have witnessed do in fact happen.

Moreover, HIPAA does not provide privacy against the police. HIPAA was written specifically so that the police can request information from hospitals. Here is the ACLU on HIPAA:

Q: Can the police get my medical information without a warrant?

A: Yes. The HIPAA rules provide a wide variety of circumstances under which medical information can be disclosed for law enforcement-related purposes without explicitly requiring a warrant.[iii] These circumstances include (1) law enforcement requests for information to identify or locate a suspect, fugitive, witness, or missing person (2) instances where there has been a crime committed on the premises of the covered entity, and (3) in a medical emergency in connection with a crime.[iv]

In other words, law enforcement is entitled to your records simply by asserting that you are a suspect or the victim of a crime.

Finally, the records in question in this case were not even patient records but visitor records. Whether or not there is an official policy on what to do while waiting at a hospital for other reasons (say to speak to a suspect) it’s plausible to me that the police in Philadelphia can and do sneak a peek at visitor records when the opportunity arises. It’s certainly the case that people who have warrants against them avoid hospitals and other institutions that keep such records for fear of arrest (and here).

I was confused by Lubet’s other big reveal, “Goffman appears to have participated in a serious felony in the course of her field work – a circumstance that seems to have escaped the notice of her teachers, her mentors, her publishers, her admirers, and even her critics.” But this didn’t escape my notice. How could it? Goffman’s crime is the climax of the book! Lubet is talking about Goffman’s action after her friend, Chuck, is murdered:

…This time, Goffman did not merely take notes – on several nights, she volunteered to do the driving. Here is how she described it:

We started out around 3:00 a.m., with Mike in the passenger seat, his hand on his Glock as he directed me around the area. We peered into dark houses and looked at license plates and car models as Mike spoke on the phone with others who had information about [the suspected killer’s] whereabouts.

One night, Mike thought he saw his target:

He tucked his gun in his jeans, got out of the car, and hid in the adjacent alleyway. I waited in the car with the engine running, ready to speed off as soon as Mike ran back and got inside (p. 262).

Fortunately, Mike decided that he had the wrong man, and nobody was shot that night.

The fact that Goffman had become one of the gang is the point. A demonstration that environment trumps upbringing. She only narrowly escaped becoming trapped by the luck of the victim’s absence. The sociology professor and the thug, entirely different lives, separated by the thinnest of margins.

Deaths in police custody, research results

The limited data available do not suggest a recent overall increase in the number of homicides by police or the racial composition of those killed, despite the high-profile cases and controversies of 2014-2015, according to a New York Times analysis. But a January 2015 report published in the Harvard Public Health Review, “Trends in U.S. Deaths due to Legal Intervention among Black and White men, Age 15-34 Years, by County Income Level: 1960-2010,” suggests persistent differences in risks for violent encounters with police: “The rate ratio for black vs. white men for death due to legal intervention always exceeded 2.5 (median: 4.5) and ranged from 2.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.1, 3.1) in 2001 to 10.1 (95% CI 8.7, 11.7) in 1969, with the relative and absolute excess evident in all county income quintiles.”

And this:

For the most recent period where statistics are available (2003-2009), the BJS found that 4,813 persons “died during or shortly after law enforcement personnel attempted to arrest or restrain them… About 60% of arrest-related deaths (2,931) were classified as homicides by law enforcement personnel.” However, among these 2,931 homicides by law enforcement personnel, 75.3% were reported to have taken place in response to a violent offense — constituting a force-on-force situation, such as an intervention with an ongoing assault, robbery or murder: “Arrests for alleged violent crimes were involved in three of every four reported homicides by law enforcement personnel.” Still, 7.9% took place in the context of a public-order offense, 2.7% involved a drug offense, and among 9.2% of all homicides by police no specific context was reported.

There is much more of interest at the Harvard Kennedy School link.

Seattle police camera sentences to ponder

In Seattle, where a dozen officers started wearing body cameras in a pilot program in December, the department has set up its own YouTube channel, broadcasting a stream of blurred images to protect the privacy of people filmed. Much of this footage is uncontroversial; one scene shows a woman jogging past a group of people and an officer watching her, then having a muted conversation with people whose faces have been obscured.

“We were talking about the video and what to do with it, and someone said, ‘What do people do with police videos?’ ” said Mike Wagers, chief operating officer of the Seattle police. His answer: “They put it on YouTube.”

There is more here, via Michelle Dawson. The article has more detail on the status of these feeds in various localities, and the debates over how public they should be.

The Effect of Police Body Cameras

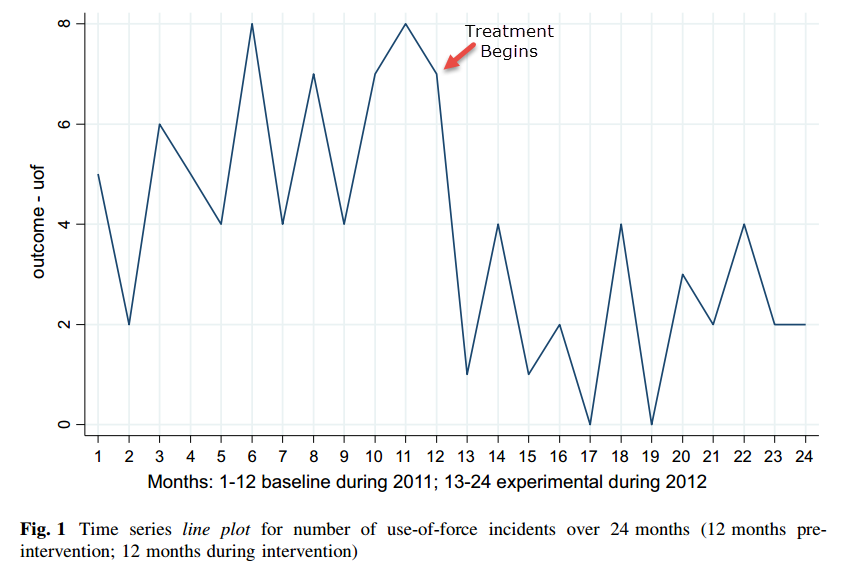

The first randomized controlled trial of police body cameras shows that cameras sharply reduce the use of force by police and the number of citizen complaints.

We conducted a randomized controlled trial, where nearly 1,000 officer shifts were randomized

over a 12-month period to treatment and control conditions. During ‘‘treatment shifts’’

officers were required to wear and use body-worn-cameras when interacting with members

of the public, while during ‘‘control shifts’’ officers were instructed not to carry or use the

devices in any way. We observed the number of complaints, incidents of use-of-force, and

the number of contacts between police officers and the public, in the years and months

preceding the trial (in order to establish a baseline) and during the 12 months of the

experiment.

The results were that police use of force reports halved on shifts when police wore cameras. In addition, the use of force during the entire treatment period (on shifts both using and not using cameras) was about half the rate as during pre-treatment periods. In other words, the camera wearing shifts appear to have caused police to change their behavior on all shifts in a way that reduced the use of force. A treatment that bleeds over to the control group is bad for experimental design but suggests that the effect was powerful in changing the norms of interaction. (By the way, the authors say that they can’t be certain whether the cameras primarily influenced the police or the citizens but the fact that the effect occurred even on non-camera shifts suggests that the effect is primarily driven by police behavior since the citizens would not have been particularly aware of the experiment, especially as there would have been relatively few repeat interactions for citizens.)

It is possible that the police shaded their reports down during the treatment period but complaints by citizens also fell dramatically during the treatment period from about 25-50 per year to just 3 per year.

Here’s a graph of use of force reports before and during the treatment period.

Police cameras will have some negative effects. When a police officer is accused of something will lawyers have the right to subpoena years of camera footage looking for anything problematic? Think about the OJ case. Perhaps tape should be erased after one year.

Nevertheless, the results of the study are impressive. More generally, I worry that there is no solution to the problem of government mass surveillance but at the very least we can turn the cameras around and even the playing field.

Does it make sense to put cameras on the police?

The Bloomberg editorial staff says no:

Videos often lack critical context, and studies have repeatedly shown that jurors can be misled by variables such as a film’s angle or focus, which can unduly sway perceptions of guilt. That cuts both ways: Footage of a protester bumping into a cop, devoid of context, could make life much easier on a prosecutor.

Police cameras are also prone to intentional abuse. With mysterious frequency, they seem to accidentally get switched off or malfunction at critical moments. One obvious remedy is to require that cops always keep them on. But that can be counterproductive. Witnesses and victims may be less forthcoming on camera. Attracting competent officers could become harder if their every interaction is recorded. Crucially, officers may simply avoid engaging certain communities, or avoid areas where confrontations are likely, if they know they’re being filmed.

Finally, equipping police with cameras and audio recorders means that they’re constantly conducting surveillance on innocent civilians — and potentially storing it all. Police frequently enter private homes and encounter people in medical emergencies who may not want to be filmed. Some officers may be tempted to record people on the basis of race or religion. And some departments have asserted that the public has no right to see such footage.

In short, a policy intended to empower the public and monitor the police could have precisely the opposite effect.

There is more here, food for thought of course. Via Adam Minter.

Police Killings

Richard Epstein writes:

Police officer deaths in the line of duty, year to date for 2014, were 67 of which 27 were by gunfire. For the full year of 2013, the numbers were 105 total deaths, with 30 by gunfire. It would be odd to say that police officer deaths (which are more common than deaths to citizens from police officers) should not count…

It would indeed be odd to say that police officer deaths should not count, which is perhaps why no one says this. Police officer deaths are counted but the literal truth is that we don’t count deaths to citizens. No one knows for sure exactly how many citizens are killed by police because the government doesn’t keep a count. Draw your own conclusions. What we do know, is that it is not true that police officer deaths are more common than deaths to citizens from police officers. Not even close.

105 officers were killed in the line of duty in 2013 but to be clear this includes heart attacks, falls, and automobile accidents. Deaths due to violent conflict include 30 deaths by gunfire, 5 vehicular assaults, 2 stabbings and a bomb. To be conservative, let’s say 50 deaths to police at the hands of citizens.

According to the FBI there are around 400 justifiable homicides by police every year, where justified is defined as the killing of a felon by a law enforcement officer in the line of duty. But note that if the killing of Michael Brown is found to be unjustified it won’t show up in these statistics.

The best information we have of citizens killed by the police, believe it or not, are private tabulations from newspaper accounts. On the basis of one such collection, DataLab at FiveThirtyEight estimates that police kill 1000 people a year.

Thus, killings by police seem to be on the order of 10 to 20 times higher than killings of police.

How the job of policeman is changing

Here is one bit from an interesting article:

Minnesota has long led the nation in peace officer standards; it’s the only state to require a two-year degree and licensing. Now, a four-year degree is becoming a more common standard for entry into departments including Columbia Heights, Edina and Burnsville. Many other departments require a four-year degree for promotion.

It’s not a rapid-fire change, but rather an evolution sped up by high unemployment that deepened the candidate pool and gave chiefs more choices. Officer pay and benefits can attract four-year candidates. Edina pays top-level officers $80,000; Columbia Heights pays nearly $75,000.

Nowadays, officers are expected to juggle a variety of tasks and that takes more education, chiefs said. Officers communicate with the public, solve problems, navigate different cultures, use computers, radios and other technology while on the move, and make split-second decisions about use of force with a variety of high-tech tools on their belt. And many of those decisions are recorded by squad car dashboard cameras, officer body cameras and even bystanders with smartphones.

There is more here, and for the pointer I thank Kirk Jeffrey.

Police, Crime and the Usefulness of Economics

In 1994 the noted criminologist David Bayley wrote:

The police do not prevent crime. This is one of the best kept secrets of modern life. Experts know it, the police know it, but the public does not know it.

Economists were skeptical based on intuition but in truth the empirical work from economists at that time was mixed with some papers showing little or no effect of police on crime, just as Bayley argued. Since Levitt’s pioneering paper, however, there have been many papers applying a wide variety of more credible research designs like natural experiments, regression discontinuity, matching and other techniques. Any one of these papers is subject to criticism but as group the results have been remarkably consistent: police reduce crime with a 10% increase in police reducing property crime by about 3-4% and violent crime a little bit more perhaps by 4-5% (average elasticities of .35 and .48 from my review paper).

Two interesting new papers add to this literature. The University of Pennsylvania has a large private police force, some 100 officers who patrol the Penn campus and a substantial fraction of the surrounding neighborhood. The city police also police the Penn neighborhood but the UP police stay within a known (but not demarcated) region. Thus, there are more police on the Penn side of the border than on the other side. MacDonald, Kick and Grunwald apply regression discontinuity to look at what happens to crime around the border region and they find that it drops as one crosses the border. Their measures of the elasticity of crime with respect to police are similar to those found elsewhere in the literature.

Chalfin and McCrary take another approach. I always assumed that the reason standard (OLS) techniques do not pick up an effect of police on crime was reverse causality, places with a lot of crime also have a lot of police. Chalfin and McCrary argue that an even more serious problem may have been measurement error. The usual measure of police is produced by the FBI and the Uniform Crime Reports. CM find another measure produced by the Annual Survey of Governments. The two measures are close enough in levels but the relationship is surprisingly weak when looking at growth rates. Although we can’t say which measure is correct (or if either are correct) just knowing that they are different tells us that measurement error is important and measurement error will bias results downward (i.e. away from showing a significant effect of police on crime.) Moreover, if you know that measurement error exists it’s also possible to correct for it (surprisingly one can do this even without knowing the truth!) and when CM do this they find large and significant effects of police on crime, very much in line with earlier results. CM also show that there is lots of variability in police numbers that is not accounted for by crime so reverse causality is not as big a problem as one might imagine.

Using a range of reasonable elasticity estimates from the new literature and a back of the envelope calculation, Klick and I argue that it would not be unreasonable to double the number of police officers in the United States. At current levels, it’s also my belief that police are much more effective than prisons at reducing crime and with far fewer of the blowback effects. Chalfin and McCrary do a more detailed cost-benefit calculation for individual cities and they also find that many cities are severely underpoliced (and some are overpoliced–the police force of Richland County, South Carolina probably does not need a tank).

Estimates of the elasticity of crime with respect to police are largely consistent across many papers which suggests that the new techniques are more credible. The elasticity estimates are also important because their size implies that major changes in policy could improve social welfare. I see the empirical economics of crime as one of the more useful areas in economics in which substantial progress has been made in recent years.