Results for “organ transplant” 69 found

Counter Intuitive Nudges

Incentives don’t always work in the way we expect and neither do nudges. The British found that different slogans to encourage organ donation had markedly different effects.

…the least successful message was: “Every day thousands of people who see this page decide to register [as an organ donor],” which ran alongside a picture of a group of smiling people.

….The most successful slogan was one which read: “If you needed an organ transplant, would you have one? If so, please help others.”

Ex-post it’s easy to come up with explanations for these differences but ex-ante these are difficult to predict. The unsuccessful slogan, for example, lets people know about a social norm; an approach that has been said to be very successful at reducing binge drinking and electricity consumption, so why didn’t it work for organ donation?

Here’s another peculiar nudge in NYC:

A counterintuitive “pilot program” aimed at reducing garbage in subway stations by removing trash cans appears, against all logic, to be working.

The idea of removing the trash cans came to the MTA in 2011 as a possible method of combating rats…But when the cans were removed from 10 stations, the agency found that not only did rat populations decrease, the amount of litter decreased, too.

My suspicion is that if this is true (and not random noise) then it’s a non-generalizable partial-equilibrium effect. If the trash cans have been removed only in some stations then people may be holding on to their trash knowing that they can dump it at the next station or in a trash can on the street. If you were to remove all or most of the cans this won’t happen.

Do you have other examples of counter-intuitive nudges? And what other explanations can you offer for the trash can effect?

Hat tip: Holman Jenkins.

Medical Self Defense

Americans have historically put great weight on the right of self-defense which is one reason why many people support the 2nd Amendment, as the Supreme Court noted explicitly in District of Columbia v. Heller. But what about medical self-defense? John Robertson argues:

A person can buy a handgun for self-defense but cannot pay for an organ donation to save her life because of the National Organ Transplantation Act’s (NOTA) total ban on paying “valuable consideration” for an organ donation. This article analyzes whether the need for an organ transplant, and thus the paid organ donations that might make them possible, falls within the constitutional protection of the life and liberty clauses of the 5th and 14th amendments. If so, government would have to show more than a rational basis to uphold NOTA’s ban on paid donations.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has rejected medical self-defense arguments for physician assisted suicide and let stand an appeals court ruling that patients do not have a right to access drugs which have not yet been permitted for sale by the FDA (fyi, I was part of an Amici Curiae brief for this case). Robertson argues, however, that these cases can be distinguished. Physician assisted-suicide doesn’t fall within a long-American tradition necessary to receive due-process rights and organ transplants are not untested or experimental. It’s a good argument although it’s disappointing that the medical self-defense principle must be unjustly delimited.

Hat tip: Law, Economic and Cycling.

Mere exposure to money

The paper is by Eugene M. Caruso, Kathleen D. Vohs, Brittani Baxter and Adam Waytz. The title of the paper is “Mere Exposure to Money Increases Endorsement of Free-Market Systems and Social Inequality.” Abstract:

The present research tested whether incidental exposure to money affects people’s endorsement of social systems that legitimize social inequality. We found that subtle reminders of the concept of money, relative to nonmoney concepts, led participants to endorse more strongly the existing social system in the United States in general (Experiment 1) and free-market capitalism in particular (Experiment 4), to assert more strongly that victims deserve their fate (Experiment 2), and to believe more strongly that socially advantaged groups should dominate socially disadvantaged groups (Experiment 3). We further found that reminders of money increased preference for a free-market system of organ transplants that benefited the wealthy at the expense of the poor even though this was not the prevailing system (Experiment 5) and that this effect was moderated by participants’ nationality. These results demonstrate how merely thinking about money can influence beliefs about the social order and the extent to which people deserve their station in life.

For the pointer I thank Robin Hanson.

Toward a 21st-Century FDA?

In a WSJ op-ed, Andrew von Eschenbach, FDA commissioner from 2005 to 2009, is surprisingly candid about how the FDA is killing people.

When I was commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 2005 to 2009, I saw firsthand how regenerative medicine offered a cure for kidney and heart failure and other chronic conditions like diabetes. Researchers used stem cells to grow cells and tissues to replace failing organs, eliminating the need for expensive supportive treatments like dialysis and organ transplants.

But the beneficiaries were laboratory animals. Breakthroughs for humans were and still are a long way off. They have been stalled by regulatory uncertainty, because the FDA doesn’t have the scientific tools and resources to review complex innovations more expeditiously and pioneer regulatory pathways for state-of-the-art therapies that defy current agency conventions.

Ultimately, however, von Eschenbach blames not the FDA but Congress:

Congress has starved the agency of critical funding, limiting its scientists’ ability to keep up with peers in private industry and academia. The result is an agency in which science-based regulation often lags far behind scientific discovery.

Should we not, however, read the following ala Strauss?

The FDA isn’t obstructing progress because its employees are mean-spirited or foolish.

…For example, in August 2010, the FDA filed suit against a company called Regenerative Sciences. Three years earlier, the company had begun marketing a process it called Regenexx to repair damaged joints by injecting them with a patient’s own stem cells. The FDA alleged that the cells the firm used had been manipulated to the point that they should be regulated as drugs. A resulting court injunction halting use of the technique has cast a pall over the future of regenerative medicine.

A peculiar example of a patient-spirited and wise decision, no? And what are we to make of this?

FDA scientists I have encountered do care deeply about patients and want to say “yes” to safe and effective new therapies. Regulatory approval is the only bridge between miracles in the laboratory and lifesaving treatments. Yet until FDA reviewers can be scientifically confident of the benefits and risks of a new technology, their duty is to stop it—and stop it they will. (emphasis added).

von Eschenbach ends with what sounds like a threat or perhaps, as they say, it is a promise. Unless Congress funds the FDA at higher levels and lets it regulate itself:

…we had better get used to the agency saying no by calling “time out” or, worse, “game over” for American companies developing new, vital technologies like regenerative medicine.

Frankly, I do not want to “get used” to the FDA saying game over for American companies but nor do I trust Congress to solve this problem. Thus, von Eschenbach convinces me that if we do want new, vital technologies like regenerative medicine we need more fundamental reform.

Compensation Now Legal for Bone Marrow Donation

Excellent news; yesterday the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a unanimous opinion stating that compensation for bone marrow donation, specifically peripheral blood stem cell apheresis, is legal because such donation does not fall under the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA).

The case was simple and it’s outrageous that the government fought. In brief, a bone marrow donation used to require inserting a very big needle into the donor’s hip bone, a painful hospital-procedure often requiring general anesthesia. Today, however, donors typically do not donate marrow but hematopoietic stem cells which can be harvested directly from blood in a procedure that takes a little longer but is essentially similar to a standard blood donation. Compensation for blood is legal (blood is excluded as an organ under NOTA). The plaintiffs, led by the Institute for Justice, argued and the court agreed that there is no rational basis for outlawing one type of blood donation when a similar donation is legal.

I was shocked by the utter boneheadedness of one of the government’s arguments:

…the government argues that because it is much harder to find a match for patients who need bone marrow transplants than for patients who need blood transfusions, exploitative market forces could be triggered if bone marrow could be bought.

In other words, markets are forbidden just when they are most useful. It was in fact the patients with rare matches who brought this case. As the court noted:

…a physician and medical school professor…says that at least one out of five of his patients dies because no matching bone marrow donor can be found, and many others have complications when scarcity of matching donors compels him to use imperfectly matched donors. One plaintiff is a parent of mixed race children, for whom sufficiently matched donors are especially scarce, because mixed race persons typically have the rarest marrow cell types.

The patients with the most common cell types can afford to rely on the kindness of strangers. You don’t need a lot of kindness when there are a lot of strangers. The patients who are most difficult to match need to leverage altruism with incentive. It’s a lesson with many applications.

Motorcycle helmet externality of the day

Our estimates imply that every death of a helmetless motorcyclist prevents or delays as many as 0.33 deaths among individuals on organ transplant waiting lists.

Here is the paper and I thank Brent Wheeler for the pointer. So should we mandate or tax the use of such helmets?

China fact of the day

It is almost unheard of for ordinary Chinese citizens to volunteer to donate their organs after death. Only about 130 people have pledged to donate their organs since 2003, the newspaper stated, quoting Chen Zhonghua, a professor at Tongji Hospital’s Institute of Organ Transplantation in Shanghai.

Here is more; the story concerns the Chinese trying to move away from harvesting the organs of deceased prisoners.

Here's a good blog post on a new Chinese leisure activity.

Lifesharers on ABC

If you had to sign your organ donor card to be eligible to receive an organ transplant the shortage of human organs for transplant would disappear. I am on the board of advisors of LifeSharers an organ donation club which has begun to implement such a system. LifeSharers and its tireless president, Dave Undis, were featured recently on ABC News Tonight. Here’s the video.

Department of Why Not?

This reminds me of one of my favorite books, encountered during research for Last Best Gifts: Ed Brassard’s Body For Sale: An Inside Look At Medical Research, Drug Testing, And Organ Transplants And How You Can Profit From Them.

This is a how-to guide for selling the renewable and non-renewable bits

of yourself and also for getting accepted into paying clinical trials

of all kinds.

Dollars for Donors

The shortage of human organs for transplant grows worse every year. Better immuno-suppressive drugs and surgical techniques have raised the demand at the same time that better emergency medicine, reduced crime and safer roads have reduced organ supply. As a result, the waiting list for organ transplants is now 82,000 and rising and more than 6000 people will die this year while waiting for a transplant.

The economics of the shortage are so obvious that one popular textbook, Pindyck and Rubinfeld’s Microeconomics, uses the organ shortage to explain the effect of price controls more generally!

Perhaps because the shortage is growing, opposition to financial compensation for cadaveric donation (compensation for live donors is a distinct issue) appears to be lessening. The AMA, the American Society of Transplant Surgeons and the United Network for Organ Sharing have agreed that tests of the idea would be desirable. (A group of clerics, doctors, economists (I am a member) and others has formed to lobby for the idea – see our letter to Congress.) Currently, even tests are illegal but Representative James Greenwood (R, Pa.) has introduced a bill (H.R. 2856) that would create an exception.

Aside from the obvious benefits of saving lives, financial compensation for organ donation would likely save money. Here is a back-of-the-envelope calculation. There are some 285,000 people on dialysis in the US. Transplants are cheaper than dialysis by something like $10-$25,000 per year. About a quarter of those on dialysis are on the waiting list but perhaps as many as half could benefit from a transplant (fewer people are put on the list because of the shortage.) Let’s take the lower numbers. Assume that a quarter of the patients on dialysis could benefit from a transplant and that cost savings are $10,000 a year for five years. Then ending the shortage would save 3.5 billion dollars. Note again that this is a lower estimate. How much would it cost to end the shortage? No one knows for certain but I think a $5000 gift to the estates of organ donors would increase supply enough to greatly alleviate the shortage – that would involve doubling the supply to 12,000 for a paltry cost of $60 million. If this is not enough – raise the gift – anyway you cut it, the savings from dialysis exceed the costs of compensating donors by a large margin.

We should in fact count the value of the lives saved. If we can save 6000 lives and value each life at 3 million dollars (a lower value than what the US government typically uses in its calculations) then that is a further gain of 18 billion dollars.

A Tragedy of the Commons? Economics provides another way of looking at the crisis. Currently we have organ socialism – anyone who needs an organ is allowed access to the organ pool regardless of whether or not they contributed to the upkeep. As with other resources owned in common we get over-exploitation and under-investment. Consider, instead a “no-give, no-take policy” – only those who have previously signed their organ donor cards are allowed access to the pool. Not only is this more moral than the current policy it creates an incentive to sign your organ donor card. Signing your card becomes the ticket to joining a club – the club of people who have agreed to share their organs should they no longer need them. Equivalently signing your organ donor card becomes analogous to buying insurance. I discuss the idea further in Entrepreneurial Economics.

An organ club has in fact been started – I am not just an adviser, I’m also a member! You can join too at www.lifesharers.com.

UNOS Kills

I’ve long been an advocate of increasing the use of incentives in organ procurement for transplant; either with financial incentives or with rules such as no-give, no-take which prioritize former potential organ donors on the organ recipient list. What I and many reformers failed to realize, however, is that the current monopolized system is so corrupt, poorly run and wasteful that thousands of lives could be saved even without incentive reform. (To be clear, these issues are related since an incentivized system would never have become so monopolized and corrupt in the first place but that is a meta-issue for another day.) Here, for example, is one incredible fact:

An astounding one out of every four kidneys that’s recovered from a generous American organ donor is thrown in the trash.

Here’s another:

Organs are literally lost and damaged in transit every single week. The OPTN contractor is 15 times more likely to lose or damage an organ in transit than an airline is a suitcase.

Organs are not GPS-tracked!

In an era when consumers can precisely monitor a FedEx package or a DoorDash dinner delivery, there are no requirements to track shipments of organs in real time — or to assess how many may be damaged or lost in transit.

“If Amazon can figure out when your paper towels and your dog food is going to arrive within 20 to 30 minutes, it certainly should be reasonable that we ought to track lifesaving organs, which are in chronic shortage,” Axelrod said.

Here’s one more astounding statistics:

Seventeen percent of kidneys are offered to at least one deceased person before they are transplanted….

Did you get that? The tracking system for patients is so dysfunctional that 17% of kidneys are offered to patients who are already dead–thus creating delays and missed opportunities.

All of this was especially brought to light by Organize, a non-profit patient advocacy group who under an innovative program embedded with the HHS and working with HHS staff produced hard data.

Many more details are provided in this excellent interview with Greg Segal and Jennifer Erickson, two of the involved principals, in the IFPs vital Substack Statecraft.

Avoiding Repugnance

Works in Progress has a good review of the state of compensating organ donors, especially doing so with nudges or non-price factors to avoid backlash from those who find mixing money and organs to be repugnant. My own idea for this, first expressed in Entrepreneurial Economics, but many times since is a no-give, no-take rule. Under no-give, no-take, people who sign their organ donor cards get priority should they one day need an organ. The great virtue of no-give, no-take is that it provides an incentive to sign one’s organ donor card but one that strikes most people as fair and just and not repugnant. Israel introduced a no-give, no-take policy in 2008 and it appears to have worked well.

In March 2008, to increase donations, the Israeli government implemented a ‘priority allocation’ policy to encourage more people to sign up to donate organs after their deaths. Once someone has been registered as a donor for three years, they receive priority allocation if they themselves need a transplant. If a donor dies and their organs are usable, their close family members also get higher priority for transplants if they need them – which also means that families are more inclined to give their consent for their deceased relatives’ organs to be used.

In its first year, the scheme led to 70,000 additional sign-ups. The momentum continued, with 11.1 percent of all potential organ donors being registered in the five years after the scheme was introduced, compared to 7.7 percent before. According to a 2017 study, when presented with the decision to authorize the donation of their dead relative’s organs, 55 percent of families decided to donate after the priority scheme, compared to 45 percent before.

Compensating Kidney Donors

The Trump administration will allow greater compensation for live kidney donors.

Supporting Living Organ Donors. Within 90 days of the date of this order, the Secretary shall propose a regulation to remove financial barriers to living organ donation. The regulation should expand the definition of allowable costs that can be reimbursed under the Reimbursement of Travel and Subsistence Expenses Incurred Toward Living Organ Donation program, raise the limit on the income of donors eligible for reimbursement under the program, allow reimbursement for lost-wage expenses, and provide for reimbursement of child-care and elder-care expenses.

While pure compensation is still illegal this goes a long way to recouping costs. In addition the executive order improves the rules that govern the organ procurement organizations with the goal of deceasing the number of wasted organs. Compensating kidney donors is a policy that I have long supported. Together the two changes could save thousands of lives. Even Dylan Matthew, a living organ donor who writes for Vox, is pleased.

Hat tip: Frank McCormick

Presumed Consent in Wales Falls Short

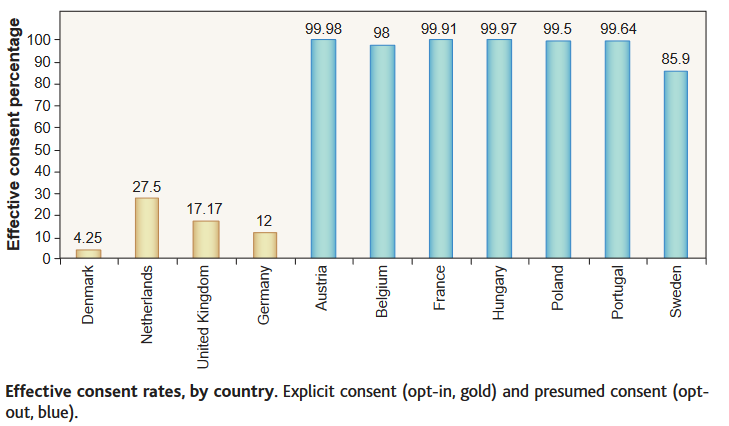

In 2003, Johnson and Goldstein published what would become a famous paper in Science, Do Defaults Save Lives? The paper featured a graph which showed organ donor consent rates in opt-in countries versus those in opt-out countries. The graph is striking because it seems to suggest that a simple change in the default rule can create a massive change in organ dono r rates and thus save thousands of lives.

r rates and thus save thousands of lives.

The graph, however, does NOT show organ donor rates. It shows that in opt-in countries few people explicitly opt-in and in presumed consent countries few people explicitly opt-out. But when a potential organ donor dies the families of people in opt-in countries who did not opt-in are still asked whether they would like to donate their loved one’s organs and many of them say yes. Similarly, in the presumed consent countries the families of people who did not opt-out are still typically asked whether they would like to donate their loved one’s organs and some of them say no.

The actual difference in organ donation rates between opt-in and presumed consent countries is much smaller than the differences in the graph, as Johnson and Goldstein made clear later in their paper. Nevertheless, the simple story in the graph encouraged many people to put excess weight on presumed consent as the solution to low organ donor rates.

The best estimates of presumed consent suggested that switching to presumed consent might increase organ donor rates by 25%. 25% isn’t bad! But we don’t have many examples of countries that have switched from one system to another so that estimate should be taken with a grain of salt.

The latest evidence comes form Wales which switched to presumed-consent in 2013. Unfortunately, there has been no increase in donation rates.

The most significant analysis of the new system is the Impact Evaluation Report, released by the Welsh Government in November 2017. Whilst focusing on the positives, such as increased understanding among medical staff, the report cannot escape the donation statistics, which clearly show no improvement. Covering the period from January 2010 or January 2011 to September 2017, all donation data show no change since the legislation’s introduction. The 21-month period before the Act came into effect saw 101 deceased donors, whereas the same period after showed 104; an increase, but one that can be properly attributed to expected annual fluctuation.

I still favor presumed consent or better, mandated choice, but I don’t think the binding constraints on organ donation are default rules. More important are preferences and fears about donation, the existence of a professional system using people who are trained to ask for donations, an institutional organization that can use donations when they are available (minimizing waste), and, of course, incentives.

Hat tip: Frank McCormick.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Chess players’ fame versus their merit.

2. Haggis recipe could be tweaked to beat U.S. ban.

3. Who has the edge in getting organs for transplant? (guess)

4. Sumner on Bernanke, more here. And it is scary that Bernanke feels the need to write a blog post opposing the notion that Congress raid the capital of the Fed. It gets sent to the Treasury anyway.

5. NYT obituary of Rene Girard, with lots on Peter Thiel too. It is also odd what this piece leaves out.