Results for “Larry Summers” 194 found

What is the equilibrium in higher education policy?

That is the topic of my Bloomberg column, here goes:

Critics of the policy see it as rewarding Democratic supporters and interest groups, including university faculty and administrators but most of all students. This perception, regardless of whether it’s true, will influence political behavior…

Republicans, when they hold political power, are likely to strike back. They may be more interested in draining the sector of revenue. The simplest way of doing this would be to limit tuition hikes in state universities. De facto tuition caps are already common, but they may become tighter and more explicit, especially in red and purple states. Such policies might also prove popular with voters, especially during a time of high inflation.

A second set of reforms might limit the ability of public universities to spend money on hiring more administrators, including people who work on so-called DEI issues. Given the fungibility of funds, and the ability of administrators to retitle new positions, such restrictions may not be entirely enforceable. Still, they would mean less autonomy for public universities as policy in many states tried to counteract their current leftward swing.

Another possible reform could tie funding for a school or major to the future earnings of graduates. That likely would penalize the humanities, which already tend to be one of the more politicized segments of the modern university…

Longer-term, a future Republican administration might decide to restructure the entire system of federal student loans. How about making student loans dischargeable through normal bankruptcy proceedings? That might sound like a pretty unremarkable idea to most voters, and many economists, including Larry Summers, favor it. It would also allow for some measure of debt relief without extending it to the solvent and the well-off.

Still, the long-term consequences of this reform would probably lead to a significant contraction of lending. Most enrolled students do not in fact finish college, and many of them end up with low net worth yet tens of thousands of dollars of debt. (By one estimate, the net worth of the median American below age 35 is $13,900.) So the incentives to declare bankruptcy could be relatively high. This would make federal student loans a more costly and less appealing proposition. Private lenders would be more wary as well. Higher education would likely contract.

The net effect of the president’s loan-forgiveness initiative — which is an executive order and thus does not have an enduring legislative majority behind it — could amount to a one-time benefit for students, no impact on rising educational costs, and the intensification of the culture wars over higher education.

Sad but true.

The tax provisions of the new climate and taxes bill

I can’t quite bring myself to call it the Inflation Reduction Act. One thing I have learned from experience is how hard it is to judge such bills upfront. For instance, I just learned that the electric vehicle tax credits do not currently apply to any electric vehicle whatsoever, nor will they obviously apply to any electric vehicle to be produced in the near future. Now the United States might take a larger role in battery production, or perhaps the law/regulation will be modified — don’t assume these standards will collapse. Still, the provisions are going to evolve. Or maybe there is a modest chance that provision of the bill simply will never kick in.

I don’t know.

How about the corporate minimum tax provisions? It sounds so simple to address unfairness in this way, and how much opposition will there be to a provision that might cover only 150 or so companies? But a lot of the incentives for new investment will be taken away, including new investment by highly successful companies. (You can get your tax bill down by making new investments, for instance, and that is why Amazon has paid relatively low taxes in many years.) Most of the companies covered are expected to be manufacturing, and didn’t we hear from the Democratic Party (and indeed many others) some while ago that manufacturing jobs possess special economic virtues? Furthermore, some of the tax incentives for green energy investments will be taken away. Has anyone done and published a cost-benefit analysis here? That is a serious question (comments are open!), not a rhetorical one.

Here are some other concerns (NYT):

“The evidence from the studies of outcomes around the Tax Reform Act of 1986 suggest that companies responded to such a policy by altering how they report financial accounting income — companies deferred more income into future years,” Michelle Hanlon, an accounting professor at the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the Senate Finance Committee last year. “This behavioral response poses serious risks for financial accounting and the capital markets.”

Other opponents of the new tax have expressed concerns that it would give more control over the U.S. tax base to the Financial Accounting Standards Board, an independent organization that sets accounting rules.

“The potential politicization of the F.A.S.B. will likely lead to lower-quality financial accounting standards and lower-quality financial accounting earnings,” Ms. Hanlon and Jeffrey L. Hoopes, a University of North Carolina professor, wrote in a letter to members of Congress last year that was signed by more than 260 accounting academics.

How bad is that? I do not know. Do you? My intuition is that the book profits concept cannot handle so much stress. By the way, kudos to NYT and Alan Rappeport for doing that piece. It is balanced but does not hold back on the skeptical side.

And here’s one matter I haven’t seen anyone mention: the climate part of the bill, and indeed most of the accompanying science and chips bill, assume in a big way that private sector investment is deficient in solving various social problems and needs some serious subsidy and direction.

Now the direction of that investment is a separate matter, but when it comes to the subsidy do you recall Kenneth Arrow’s classic argument that the private sector does not invest enough in risk-taking? Private investors see their private risk as higher than the actual social risk of the investment. This argument implies subsidies for investments, as much of the rest of the bill and its companion bill provide, not additional taxes on investment. This same kind of argument lies behind Operation Warp Speed, which most people supported, right?

And yet I see everyone presenting the new taxes on investment in an entirely blithe manner, ignoring the fact that the rest of the bill(s) implies private investment needs to be subsidized or at least taxed less.

Overall the ratio of mood affiliation and also politics in this discussion, to actual content, makes me nervous. The bills went through a good deal of uncertainty, and so a significant portion of the intelligentsia has been talking them up. Biden after all needs some victories, right? And at some point the green energy movement needs some major legislative trophies, right? What I’d like to see instead is a more open and frank discussion of the actual analytics.

It is very good when a top economist such as Larry Summers has real policy influence, in this case on Joe Manchin. But part of that equilibrium is that other economists start watching their words, knowing some other Democratic Senator might fall off the bandwagon. There is Sinema, Bernie Sanders has been making noise and complaining, someone else might have tried to extract some additional rents, and so on.

The net result is that you are not getting a very honest and open discussion of what is likely to prove a major piece of legislation.

Why is the U.S. inflation rate especially high?

However, since the first half of 2021, U.S. inflation has increasingly outpaced inflation in other developed countries. Estimates suggest that fiscal support measures designed to counteract the severity of the pandemic’s economic effect may have contributed to this divergence by raising inflation about 3 percentage points by the end of 2021.

That is from a recent San Francisco Fed piece by Òscar Jordà, Celeste Liu, Fernanda Nechio, and Fabián Rivera-Reyes.

I recall not so long ago when the overwhelming majority of Democratic-leaning economists on Twitter and elsewhere strongly favored the additional $2 trillion in stimulus. In the campaign, it was a kind of electorally defining policy of the Biden administration. I also recall that Larry Summers explained in very clear terms why this was the wrong policy, and hardly anyone listened. “Progressive catnip” is the phrase I use to describe such policy options. It involved “stimulus,” “sending people money,” and it “boosted demand,” all popular catchphrases of the moment. It was seen as part of a broader push simply to be sending people money all the time.

This has to count as one of the biggest economic policy failures of recent times, and we still are not taking seriously that it happened and what that implies for our collective epistemic capabilities moving forward.

Tuesday assorted links

2. “The first lunar dust collected by Neil Armstrong from the Apollo 11 mission in 1969 is headed to auction, with an estimated value of between US$800,000 and US$1.2 million.” Link here.

3. What will the end of subsidies mean for uninsured Covid care?

4. Ezra Klein and Larry Summers (NYT).

5. New and relatively rigorous study of social media and well-being. Small negative effects, highly dependent on age, somewhat dependent on gender. Evidence consistent with causality running in both directions. This is not a zero negative effect, stronger than usual for girls 12-14, and for men 26-29, but overall not consistent with the doomsaying accounts. Here is NYT coverage. Note this from the NYT: ““There’s been absolutely hundreds of these studies, almost all showing pretty small effects,” said Jeff Hancock, a behavioral psychologist at Stanford University who has conducted a meta-analysis of 226 such studies.”

Monday assorted links

1. Is there a Groundhog Day effect in stock markets?

2. We acquire energy more rapidly than our ape cousins.

3. The wisdom of Larry Summers (antitrust and inflation). And more on student loans.

4. Brandon is finding it hard to get endorsements.

5. Wayne Thiebaud, RIP, passed away at 101 (NYT).

Nellie Bowles interviews me on inflation

So I called someone smart (Tyler Cowen, an economist, author, and professor at George Mason University) to explain the dynamics to me.

“Inflation right now is still transitory in that we can choose to end it,” Cowen told me. The Federal Reserve could disinflate and raise interest rates—mortgage interest rates today remain well below 3%—though that risks starting a recession.

Cowen explained that the reason the inflation-wary are still pretty quiet is that all the anti-Obama Republicans were so wrong in 2008. After the Obama-era bailout during the Great Recession, Republicans were convinced inflation would run rampant. And they said so. A lot. But inflation stayed mostly in control. “They all got egg on their faces after that,” Cowen said. “So the crowd that would complain now, they’re whispering about it but not shouting yet.” (Larry Summers and Steve Rattner have sounded the alarm.)

“I think the inflation will last two to three years, and it will be bad,” Cowen said. But really grim hyper-inflation à la Carter-era, he thinks is unlikely. It could only happen if the Federal Reserve decides it’s too risky to trim the sails of cheap money. “I’d put it at 20% chance that the Fed will think, ‘Trump might run again, and we don’t want Biden to lose . . . history’s in our hands, so we’ll wait to tighten.’ And then it just goes on, and then it’s very bad.”

But a recession is also bad. It’s hard to sort it all out. “As the saying goes, ‘If you’re not confused, you don’t know what’s going on,’” Cowen told me.

That is from the Bari Weiss Substack, other topics are considerd (not by me) at the link.

The University of Austin

A new university is being founded. Here is part of the statement from its new president, Pano Kanelos:

As I write this, I am sitting in my new office (boxes still waiting to be unpacked) in balmy Austin, Texas, where I moved three months ago from my previous post as president of St. John’s College in Annapolis.

I am not alone.

Our project began with a small gathering of those concerned about the state of higher education—Niall Ferguson, Bari Weiss, Heather Heying, Joe Lonsdale, Arthur Brooks, and I—and we have since been joined by many others, including the brave professors mentioned above, Kathleen Stock, Dorian Abbot and Peter Boghossian.

We count among our numbers university presidents: Robert Zimmer, Larry Summers, John Nunes, and Gordon Gee, and leading academics, such as Steven Pinker, Deirdre McCloskey, Leon Kass, Jonathan Haidt, Glenn Loury, Joshua Katz, Vickie Sullivan, Geoffrey Stone, Bill McClay, and Tyler Cowen [TC: I am on the advisory board].

We are also joined by journalists, artists, philanthropists, researchers, and public intellectuals, including Lex Fridman, Andrew Sullivan, Rob Henderson, Caitlin Flanagan, David Mamet, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Sohrab Ahmari, Stacy Hock, Jonathan Rauch, and Nadine Strossen.

You can follow the school on Twitter here.

Friday assorted links

1. “Given these results, we show that it may be optimal to visit restaurants in a zigzag that alternates between high- and low-quality choices.” I am not endorsing that one!

2. Jordan Schneider podcast has Larry Summers on China.

3. Is your “aha!” moment actually the announcement of a meta-cognition prediction error?

4. Long Twitter thread on Maimonides.

5. Immunological dark matter hypothesis is being revived. And what might the Delta wave look like in the U.S.?

6. Louis Andriessen, RIP (NYT): “Mr. Andriessen wrote that in Mr. Greenaway’s films, “I recognize something of my own work, namely the combination of intellectual material and vulgar directness.””

Lies vs. silence?

That is the contrast in my latest Bloomberg column. The claims about the Republicans are more widely circulated in educated circles, so here is the section on the Democrats:

Given the greater deployment of intellectual argument, smart, educated people are exposed to a more persuasive case for Democratic positions. But there is a danger in this asymmetry: when Democratic ideas are not working or are poorly designed.

Rather than constructing brazen untruths, the Democratic intelligentsia remains largely silent when it is unhappy. President Joe Biden’s recent Buy American plan is similar to protectionist ideas from Trump, but it doesn’t come in for heavy criticism on social media. If asked about it, most Democratic-leaning economists would be (correctly) critical. Yet for them this shortcoming isn’t that big a deal, given what are perceived to be the greater sins of Republicans, including their “big lie” strategy.

The continuing problems of migrant children cut off from their parents at the border receive some criticism — but the noise machine is nothing close to what it was under Trump. The new inflation data seem to indicate that Larry Summers’s criticisms of Biden’s stimulus program were largely correct, yet few if any commentators are apologizing to him on Twitter.

There is much more at the link, including about Republicans. And to be clear, when it comes to the Democrats, the “in fact this wasn’t left wing enough” is an almost obligatory form of self-criticism, serving also as a kind of repeated affirmation of relative moral superiority. Or the “I/we was even more right than I had thought” criticism is common as well. The actual self-criticism of “our value schema led us astray on this issue altogether”? — you almost never hear that one.

Our aggregate demand shortfall?

From Ben Casselman: “…unlike with most measures of the economy, retail sales are actually ABOVE their prepandemic level. Up 2.6% from February, and 2.9% over the past year. So not a clean story like with jobs.”

And from Larry Summers: ” Total household income is 8% above what anybody thought it would be before Covid.”

And from Larry Summers: ” Total household income is 8% above what anybody thought it would be before Covid.”

There are very real macroeconomic problems right now, but please keep the following in mind while drawing up a “demand-based” stimulus plan. Focus on public health!

Christmas assorted links

1. Black-footed ferrets are getting their own Covid-19 vaccine.

3. David Brooks’s Sidney awards (NYT).

4. In memory of Richard Cooper, Harvard economist.

5. When Larry Summers is trending on Twitter, he is usually correct.

6. My Bloomberg column on all the scientific developments of 2020. Hail computation!

7. Vaccine envy (NYT). And “NBA memo warns teams about obtaining, administering COVID-19 vaccine early.”

8. One Texas health district received 900 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. Then, it closed for Christmas.

10. Turkey Finds Chinese Vaccine Efficacy Rate of 91.25% in Trial.

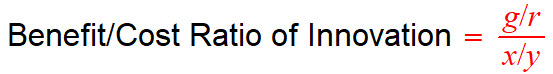

A Calculation of the Social Returns to Innovation

Benjamin Jones and Larry Summers have an excellent new paper calculating the returns to social innovation.

This paper estimates the social returns to investments in innovation. The disparate spillovers associated with innovation, including imitation, business stealing, and intertemporal spillovers, have made calculations of the social returns difficult. Here we provide an economy-wide calculation that nets out the many spillover margins. We further assess the role of capital investment, diffusion delays, learning-by-doing, productivity mismeasurement, health outcomes, and international spillovers in assessing the average social returns. Overall, our estimates suggest that the social returns are very large. Even under conservative assumptions, innovation efforts produce social benefits that are many multiples of the investment costs.

What was interesting to me is that their methods of calculation are obvious, almost trivial. It can take very clever people to see the obvious. Essentially what they do is take the Solow model seriously. The Solow model says that in equilibrium growth in output per worker comes from productivity growth. Suppose then that productivity growth comes entirely from innovation investment then this leads to a simple expression:

Where g is the growth rate of output per worker (say 1.8% per year), r is the discount rate (say 5%), and x/y is the ratio of innovation investment, x, to GDP, y, (say 2.7%). Plugging the associated numbers in we get a benefit to cost ratio of (.018/.05)/.027=13.3.

Where g is the growth rate of output per worker (say 1.8% per year), r is the discount rate (say 5%), and x/y is the ratio of innovation investment, x, to GDP, y, (say 2.7%). Plugging the associated numbers in we get a benefit to cost ratio of (.018/.05)/.027=13.3.

To see where the expression comes from suppose we are investing zero in innovation and thus not growing at all. Now imagine we invest in innovation for one year. That one year investment improves economy wide productivity by g% forever (e.g. we learn to rotate our crops). The value of that increase, in proportion to the economy, is thus g/r and the cost is x/y.

Jones and Summers then modify this simply relation to take into account other factors, some of which you have undoubtedly already thought of. Suppose, for example, that innovation must be embodied in capital, a new design for a nuclear power plant, for example, can’t be applied to old nuclear power plants but most be embodied in a new plant which also requires a lot of investment in cement and electronics. Net domestic investment is about 4% of GDP so if all of this is necessary to take advantage of innovation investment (2.7% of gdp), we should increase “required” to 6.7% of GDP which is equivalent to multiplying the above calculation by 0.4 (2/7/6.7). Doing so reduces the benefit to cost ratio to 5.3 which means we still get a very large internal rate of return of 27% per year.

Other factors raise the benefit to cost ratio. Health innovations, for example, don’t necessarily show up in GDP but are extremely valuable. Taking health innovation cost out of x means every other R&D investment must be having a bigger effect on GDP and so raises the ratio. Alternatively, including health innovations in benefits, a tricky calculation since longer life expectancy is valuable in itself and raises the value of GDP, increases the ratio even more. (See also Why are the Prices So Damn High? on this point). International spillovers also increase the value of US innovation spending.

Bottom line is, as Jones and Summers argue, “analyzing the average returns from a wide variety of perspectives suggests that the social returns [to innovation spending] are remarkably high.”

Operation Warp Speed Needs to Go to Warp 10

Operation Warp Speed is following the right plan by paying for vaccine capacity to be built even before clinical trials are completed. OWS, however, should be bigger and should have more diverse vaccine candidates. OWS has spent well under $5 billion. At current rates, the US economy is losing about $40 billion a week. Thus, if $20 billion could advance a vaccine by just one week that would be a good deal. As I said in the LA Times, “It might seem expensive to invest in capacity for a vaccine that is never approved, but it’s even more expensive to delay a vaccine that could end the pandemic.”

I am also concerned that OWS is narrowing down the list of candidates too early:

NYTimes: Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and the Oxford-AstraZeneca group have already received a total of $2.2 billion in federal funding to support their vaccine programs. Their selection as finalists, along with Merck and Pfizer, will give all five companies access to additional government money, help in running clinical trials and financial and logistical support for a manufacturing base that is being built even before it is clear which if any of the vaccines in development will work.

These are all good programs and one of them will probably be successful but we also want to support some long-shots because a small probability of a very big gain is still a big gain.

The five candidates also all use new technologies and are less diverse than I would prefer. There are a lot of different vaccine platforms, Live-Attenuated, Deactivated, Protein Subunit, Viral Vector, DNA and mRNA among others. The Accelerating Health Technologies team that I am a part of collected data on over 100 vaccine candidates and their characteristics. We then created a model to compute an optimal portfolio. We estimated that it’s necessary to have 15-20 candidates in the portfolio to get to a 80-90% chance of at least one success and that you want diverse candidates because the second candidate from the same platform probably fails if the first candidate from that platform fails. Moderna and Pfrizer are both mRNA vaccines–a platform that has never been used before–while AstraZeneca, Johnson and Johnson and Merck are using somewhat different viral vector platforms (Adenovirus for AstraZeneca and J & J and measles for Merck) which is also a relatively novel approach. I think it would be better if there were some tried and true platforms such as a Deactivated or Protein Subunit vaccine in the mix. As Larry Summers said, “if you will die of starvation if you don’t get a pizza in two hours, order 5 pizzas”. I would change that to order 10 pizzas and order from different companies!

One way to diversify the portfolio is to make deals with other countries to avoid the prisoner’s dilemma of vaccine portfolios. The prisoner’s dilemma is that each country has an incentive to invest in the vaccine most likely to succeed but if every country does this the world has put all its eggs in one basket. To avoid that, you need some global coordination. One country invests in Vaccine A, the other invests in Vaccine B and they agree to share capacity regardless of which vaccine works.

So my critique is that OWS is good policy but it would be even better if more vaccine candidates and more diverse vaccine candidates were part of the program. In contrast, the critiques being offered in Congress are ridiculous and dangerous.

Democrats in Congress are already seeking details about the contracts with the companies, many of which are still wrapped in secrecy. They are asking how much Americans will have to pay to be vaccinated and whether the firms, or American taxpayers, will retain the profits and intellectual property.

How much will Americans have to pay to be vaccinated??? A lot less than they are paying for not being vaccinated! The worry about profits is entirely backwards. The problem is that the profits of vaccine manufacturers are far too small to give them the correct social incentives not that the profits are too large. The stupidity of this is aggravating.

Skepticism about Trump administration policies is understandable but I am concerned that one of the best things the Trump administration is doing to combat the virus will be impeded and undermined by politics.

Saturday assorted links

2. How is cocaine trafficking doing?

3. Edenville dam failure caught on video.

4. Ten arguments against immunity passports. I mean…those are the arguments you should make. But there is no conception that you have to “solve for the equilibrium” if there are no formal immunity passports, and compare the two situations in terms of cost, unfairness, and the like. In that sense the authors cannot conceive that there needs to be a comparison at all.

6. Do proponents of moral outrage wish to “sneak up on women”? That would explain a lot.

7. The import of super-spreaders in Israel.

8. American Interest interview with Larry Summers. “LHS: There’s a lot of empirical evidence since Keynes wrote, and for every non-employed middle-aged man who’s learning to play the harp or to appreciate the Impressionists, there are a hundred who are drinking beer, playing video games, and watching 10 hours of TV a day.” It’s a good thing that has nothing to do with subsequent delayed re-employment (also known as “unemployment”), isn’t it?

Friday assorted links

1. Scott Alexander reviews Toby Ord’s The Precipice, about existential risk.

3. A critique of the Paycheck Protection Program — it might help already stable restaurants the most. See also this tweet storm.

4. Should we pivot to a service trade agenda?

5. Full paper assessing health care capacity in India.

6. Claims about Covid and the future economics of cultural institutions.

7. I could link to Matt Levine every day, but do read this one on liquidity transformation.

8. How is the cloud holding up? A good post.

9. Immunity segregation comes to Great Britain.

10. Robin Hanson on the variance in R0 and how hard it is to halt the spread of the virus.

11. New program for on-line “Night Owls” philosophy by Agnes Callard.

12. The true story of the toilet paper shortage: it’s not about hoarding, rather a shift of demand away from the commercial sector into the household sector (you are doing more “business” at home these days).

13. “U.S. ALCOHOL SALES INCREASE 55 PERCENT IN ONE WEEK AMID CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC.”

14. Fan, Jamison, and Larry Summers 2016 paper on the economics of a pandemic. I wrote at the end of the blog post: “In other words, in expected value terms an influenza pandemic is a big problem indeed. But since, unlike global warming, it does not fit conveniently into the usual social status battles which define our politics, it receives far less attention.”

15. Buying masks from China just got tougher.

16. How to produce greater capacity flexibility for hospitals.