Results for “control premium” 56 found

A very good article on health care economics

By David Goldhill, here is one bit:

How am I supposed to be able to afford health care in this system?

Well, what if I gave you $1.77 million? Recall, that’s how much an

insured 22-year-old at my company could expect to pay–and to have paid

on his and his family’s behalf–over his lifetime, assuming health-care

costs are tamed. Sure, most of that money doesn’t pass through your

hands now. It’s hidden in company payments for premiums, or in Medicare

taxes and premiums. But think about it: If you had access to those

funds over your lifetime, wouldn’t you be able to afford your own care?

And wouldn’t you consume health care differently if you and your family

didn’t have to spend that money only on care?

Here is another:

From 2000 to 2005, per capita health-care spending in Canada grew by 33

percent, in France by 37 percent, in the U.K. by 47 percent–all

comparable to the 40 percent growth experienced by the U.S. in that

period. Cost control by way of bureaucratic price controls has its

limits.

His preferred reform reminds me of Brad DeLong's plan, namely universal catastrophic care combined with required HSAs at lower levels of expenditure.

“Guns don’t kill people, trading guns does”

Well, that is a joke of sorts. But here is Jim Kessler’s piece on deepening gun ownership. He writes:

There are 280 million firearms in private hands in America, and last

year there were about 300,000 gun crimes. That means that at least

279,700,000 guns did nothing wrong. We also know that in 89 percent of

crimes, the person using the gun was not the person who originally

bought it. In 34 percent of crimes, the firearm was bought in one state

and used in a crime in another. And in 32 percent of crimes, the

firearm was less than three years old.This indicates that the root of America’s gun crime problem is not

the number of guns in the hands of Americans, but an extensive web of

gun trafficking operations that funnel firearms to criminals.

…The first step is to make gun trafficking a federal crime, not a

term of art…Trafficking should be redefined as selling multiple guns out of a

home, car, street, or park that have two or more of the following

characteristics: obliterated serial numbers, are stolen, are new in the

box, or are sold to underage buyers or people with felony records. This

would still allow individuals to privately sell firearms to people they

know or trust, and it would put the onus on sellers to demand a

background check for those they don’t.

None of this seems quite right to me. It seems to confuse "how things are done now" with "how things could be done if people needed substitutes." For instance if this proposal were adopted, criminals might acquire guns at a young age and simply never give them up. (Think of the idea as raising the liquidity premium on owning a gun.) Or criminals might buy more guns from each other. I can see that it makes sense to shut off some avenues of gun flow, such as gun sale shows with no buyer verification. But once the stock of guns is high, I don’t think trying to control the flow is likely to prove an effective means of gun control. Forcing the seller to verify the quality of the buyer is one form of a tax, and yes it will raise the price, but it is in turn hard to verify how well the seller performed this responsibility. It seems less efficient than a simple and direct excise tax, for instance.

Addendum: Alternatively, you might pose a tax incidence question: how does taxing the stock of guns differ from taxing the flow of trade? Both will raise price but taxing the flow limits "the velocity" of guns. Taxing the flow should hurt "whim killers" but it won’t so much discourage regular killers. The former get all the publicity but are they really the bigger problem?

All you can eat?

Allegedly tipped off by senior officials close to the matter, the Financial Times suggests that Apple is in talks with music labels to follow an approach first pioneered by Nokia and Universal Music Group.

Dubbed Comes With Music, the upcoming service has customers pay more for a cellphone in return for as many a la carte

music downloads as the customer likes over the course of a year. In

this implementation, customers can either renew a subscription once it

expires or else keep the tracks they’ve downloaded, even if they switch

to competing phones or music services.

Here is the article. One point is that songs will get shorter and their best riffs will be held to higher standards of immediate accessibility. If the marginal cost of a song is free, people will sample lots more and they will give fewer songs a second listen (higher opportunity cost); of course the opening bits of a song are already free in many cases but this will make sampling even easier.

Second, this will redistribute more of the market surplus away from song providers and toward hardware providers. Say everyone bought the "all you can eat" version and Apple received zero revenue per song (there are few songs that will swing a decision to subscribe or not). TAddendumhat helps Apple in its bargains with individual song providers. If you have a hit song, and Apple controls iTunes, there’s an element of bilateral monopoly. So Apple is better off if it can precommit to not caring whether they have your song or not. On the music company side, there would be a tendency toward consolidation, and bargaining over catalogs rather than songs, to offset Apple’s new bargaining advantage.

What other effects can you think of?

Addendum: Some sources are claiming this is just a rumor.

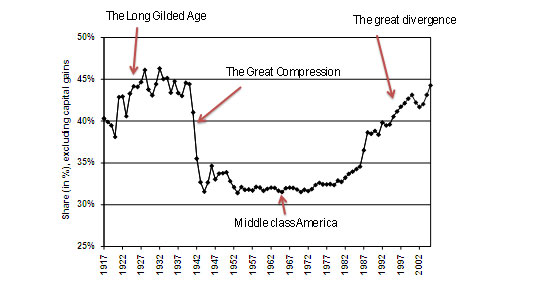

The Great Compression

Paul Krugman recently blogged:

The middle-class society I grew up in didn’t evolve gradually or automatically. It was created,

in a remarkably short period of time, by FDR and the New Deal. As the

chart shows, income inequality declined drastically from the late 1930s

to the mid 1940s, with the rich losing ground while working Americans

saw unprecedented gains.

As you can see, the share of the top ten percent (not counting capital gains) falls steeply at about 1937 and flattens out by about 1942-43, with a slight uptick just afterwards. But I am puzzled by Krugman’s description of the process. A few points:

1. 1937-38 were disastrous years for the American economy and also for the middle class, mostly because of bad contractionary monetary policy. This can be considered a second Great Depression and it aborted a recovery in process. Robert Higgs has shown convincingly that World War II was an economic disaster, look at the figures at consumption don’t be fooled by aggregate gdp which is inflated by production for the war.

2. Therefore I am not sure when the "unprecedented gains" came during this period. Yes 1940 was a year of recovery (and part of 1939) but is the claim that the middle class was created in that year? Surely not but then I am confused.

3. Krugman cites "strong unions, a high minimum wage, and a progressive tax system" as driving the Great Compression — did these factors change so notably in 1937-44?

4. In real terms, relative to the time, the new federal minimum wage of 1938 was not especially high, even compared to the minimum wage today. And the data are for pre-tax incomes, which means that progressive taxation is unlikely the major part of the story about the distribution of pre-tax income (noting the Yglesias caveat that the rate of tax will influence pre-tax incomes through labor supply).

5. Here are some data on U.S. unionization. The history does broadly track Krugman’s time frame, as long as one does not obsess over 1937-43 as being special. Note that optimistic estimates of the union wage premium today run about 15 percent, so it is hard to see unionization as the dominant factor in the change in the distribution of income.

6. The wartime economy, and the scarcity of labor, bid up wages for black workers, women, and many remaining non-drafted male laborers (due to forced saving, however, consumption was low).

7. My explanation of the break in the chart emphasizes a combination of events: top incomes were crushed by the depression of 1937-8, the war economy put a further lid on top of high incomes (for reasons of law and norms; surely the phrase "wartime wage and price controls" deserves to be uttered at least once), and the war economy bid up wages for many people near the bottom and middle of the distribution. The wealthy classes financed a disproportionate chunk of World War II, it seems.

8. Krugman mentions none of the factors listed in #7. Admittedly I may be wrong, but are not those factors obvious candidates for an explanation?

9. It is a vitally interesting question why postwar America stayed at this new percentile distribution of income (more or less), even after recovery from the war. It may be possible to defend a version of Krugman’s broader hypothesis — policy matters for income distribution — in this setting, but the story then puts greater stress on both the equalizing effects of catastrophes and also on path-dependence. That story might also suggest that strongly negative real shocks would be needed once again to make income distribution much more egalitarian.

10. How about this for an alternative story: "Crush the incomes at the top and then make the fat cats pay much higher wages to protect the world and become a superpower. Impose wage and price controls as well. See how long it takes before these distributional effects — which don’t exactly match the distribution of economic talent– reverse themselves in the aggregate." I’m not sure that’s right but at least it seems to match more of the history.

I am sensitive to the claim that many people misinterpret the words of Paul Krugman, so please do read his whole post. If he addresses these matters in more detail in his forthcoming book, I will let you know.

Unions really really don’t matter that much these days…

Idlehands points to this paper (QJE 2004) by John DiNardo and David Lee. Neither author is a crazy right-winger, let’s hear their message:

Economic impacts of unionization on employers are difficult to estimate in the absence of large, representative data on establishments with union status information. Estimates are also confounded by selection bias, because unions could organize at highly profitable enterprises that are more likely to grow and pay higher wages. Using multiple establishment-level data sets that represent establishments that faced organizing drives in the United States during 1984-1999, this paper uses a regression discontinuity design to estimate the impact of unionization on business survival, employment, output, productivity, and wages. Essentially, outcomes for employers where unions barely won the election (e. g., by one vote) are compared with those where the unions barely lost. The analysis finds small impacts on all outcomes that we examine; estimates for wages are close to zero. The evidence suggests that-at least in recent decades, the legal mandate that requires the employer to bargain with a certified union has had little economic impact on employers, because unions have been somewhat unsuccessful at securing significant wage gains.

Keep in mind what this means. Once we control for endogeneity in where unions are formed, there may not be a union wage premium at all. (A few posts ago I was telling you it was 10 to 20 percent, learn something new every day, etc.) I learned also that when we look for the wage premium in establishment-level data, rather than household data, it usually isn’t there. And that’s without considering the contribution and method of the authors.

I would like the highly intelligent left-wing part of the blogosphere to respond to this paper and to the Hirsch piece. Here is an NBER version, here are other copies. By the standards of labor economics, it does not suffice to note that the 1950s had both a more equal income distribution and more unions, or to call Western Europe a kinder, gentler place. Those citations don’t sort out cause and effect, and in fact we do have more advanced ways of scrutinizing the data.

It is fair to say that these papers do not support the "right-wing scaremongering" scenarios about unions. So a Kevin Drum might claim: "well, it can’t hurt to try more unions." That still represents a significant downgrading of the original vision. Unions are an emotional issue for the left, much as free trade and the fall of communism are so for the right. Would it not be meaningful and rallying for the left to have the battle over collective bargaining once again? But I am telling you all, there simply isn’t that much there.

By the way, here is Bloggingheads.tv with Megan and Matt on unions, can you imagine that?

What went wrong with red delicious apples?

I now find these apples inedible. Why? Falling prices led to overbreeding and lack of care:

Who’s to blame for the decline of Red Delicious? Everyone, it seems. Consumers were drawn to the eye candy of brilliantly red apples, so supermarket chains paid more for them. Thus, breeders and nurseries patented and propagated the most rubied mutations, or "sports," that they could find, and growers bought them by the millions, knowing that these thick-skinned wonders also would store for ages…

The Washington harvest begins in mid-August and runs to late October, and most apples sold through December are simply stored in refrigerated warehouses. Fruit shipped later in this cycle is kept in a more sophisticated environment called controlled-atmosphere storage — airtight rooms where the temperatures are chilly, the humidity high and the oxygen levels reduced to a bare minimum to arrest aging. Last year’s fruit will be sold through September, just as the new harvest is in full swing.

Storage apples must be picked before all their starches turn to sugar. Pick too late, and the apple turns mealy in the supermarket, but pick too soon, and the apple will never taste sweet. Growers test for optimum conditions, but today’s popular strains of Red Delicious turn color two to three weeks before harvest, making it difficult for pickers to distinguish an apple that is ready from one that isn’t…

The grower could deliver a better apple by harvesting a tree in two or three waves — the outside fruit ripens earlier than fruit in the center of the tree. This is done for Galas and other premium varieties, but the prices for Red Delicious are so depressed that farmers can’t afford that. "You would put yourself out of business," said Roger Pepperl, marketing director for Stemilt Growers Inc., a major grower in Wenatchee. In addition, the redder strains’ thicker skins, found to be rich in antioxidants, taste bitter to many palates.

The bottom line is that this practice has backfired. Consumers are no longer looking to buy artificial fruits simply for their color or durability. Here is the full story, and please support this trend by refusing to buy the standard red delicious apple.

Prescott on Social Security Reform

Recent Nobelist Ed Prescott comes out swinging for social security reform in a fine article in the WSJ.

Some politicians have vilified the idea of giving investment freedom to

citizens, arguing that those citizens will be exposed to risks inherent in the

market. But this is political scaremongering. U.S. citizens already utilize

IRAs, 401Ks, PCOs, Keoghs, SEPs and other investment options just fine, thank

you….Consumers already

know how to invest their money — why does the government feel the need to

patronize them when it comes to Social Security?

It would be one thing if the government’s Social Security system

paid a decent return, but as the President’s Commission reported, for a single

male worker born in 2000 with average earnings, the real annual return on his

currently-scheduled contributions to Social Security will be just 0.86%. … A bank would have to offer a pretty fancy toaster to

get depositors at those rates of return.

Further, about two dozen countries have reformed their state-run

retirement programs, including Chile, Sweden, Australia, Peru, the U.K.,

Kazakhstan, China, Croatia and Poland. If citizens in these countries can handle

individual savings accounts, especially citizens in countries without a history

of financial freedom, then U.S. citizens should be equally adept. At a time when

the rest of the world is dropping the vestiges of state control, the United

States should be leading the way and not lagging behind.

Prescott sees two economic benefits of private accounts, higher savings and greater labor supply (see my earlier post). Brad DeLong has argued that investing in the market makes sense only if the equity premium is a market failure and not a response to risk. At best, however, the market failure argument is a sufficient but not necessary reason for market investment. We don’t really understand the equity-premium, however, so Prescott is right to focus on higher savings and greater labor supply – neither of these benefits of private accounts requires a non risk-adjusted premium. Prescott’s focus is especially revealing because it was he and Rajnish Mehra who first brought the profession’s attention to the equity-premium puzzle.

Some thoughts on health care

I had prepared a post on health care for the ongoing WSJ.com on-line debate, but the topic was changed to fiscal policy. Here is what I had in mind:

Most plans for greater government involvement cite the large number of uninsured Americans, over 40 million at last count. The number is taken out of context, as many of these individuals are otherwise covered, choose not to purchase insurance, or are recent immigrants; read more here.

I doubt if insurance will disappear as the dominant means of payment in the health care industry. The risks are too high and the anxieties too great. So we need to improve the workings of private health insurance. It remains a mystery, why private health insurance has performed badly in holding down costs. Companies compete fiercely to shed costly patients but they do less to invest in reputations for reliability and trustworthiness. Similarly, it is a puzzle why HMOs don’t do more to invest in good reputations; lately Kaiser has moved in this direction.

Nobody has a truly good health care plan at this point. But we do know that competition for quality service has been the driving force behind the benefits of modernity. We need to figure out how to bring this to bear on health insurance. In the meantime we need to control Medicare; I suggest means-testing, here is another worthwhile proposal.

Bush’s plan encourages health savings accounts (HSA). HSAs give you a tax-free account for medical expenses but requires purchase of a high-deductible health care plan (above $1000 for individuals and $2000 for families, in most cases). And when age 65 comes, you can use the money for Medicare premiums or simply pull it out and pay standard rates of taxation. The accounts are now rising in popularity, although they remain small in absolute terms.

The plan has some admirable economic elements. It provides a tax-free vehicle for savings; most economists agree that capital income should not be taxed. But it is less of a health care plan. Most of the potential beneficiaries from HSAs already receive excellent levels of care. In sum, I like the idea of market incentives, but do not believe that HSAs will do much to make us healthier.

Strengthening competition in health care markets

Michael Porter offers some suggestions for restructuring competition in the sector:

…competition in the health care system occurs at the wrong level, over the wrong things, in the wrong geographic markets, and at the wrong time. Competition has actually been all but eliminated just where and when it is most important.

We should have more competition for service and innovation and less competition for cost-shifting:

In a healthy system, competition at the level of diseases or treatments becomes the engine of progress and reform. Improvement feeds on itself. For that process to begin, however, the locus of competition has to shift from “Who pays?” to “Who provides the best value?”

This implies some specific proposals, including the following:

1. Greater specialization of providers and facilities.

2. Large deductibles combined with medical savings accounts. But most importantly, copayments should be the same both “within the network” and “outside of the network.”

3. Transparent prices independent of group affiliation.

4. Public availability of provider track records.

5. Better risk pooling for the self-employed. And do not allow premium boosts for the sick.

6. No malpractice suits in all but extreme cases.

7. A federal mandate for minimum standards of health insurance coverage.

In Porter’s view “Attempts to limit patients’ choices or to control physicians’ behavior would end.”

My main worries: Let’s say insurers can’t get rid of people. Won’t they simply decrease the quality of service to their most costly charges? If reputational forces won’t stop insurers from unloading the sick, how will those same forces stop them from treating the sick badly? Yes transparency will be greater, but is such bad behavior today any secret? Can the federal government really regulate every margin of service?

My second worry is how all these changes will be implemented and enforced in a radically decentralized system. We might end up with more centralized control than, say, the Democrats are contemplating. That is unlikely to favor beneficial market incentives. In essence the whole proposal could amount to nationalizing the insurance industry.

Here is one short account of the proposal, with a longer version available for $5.

What are the Democrat health care plans?

Dr. Rangel offers a summary:

1. Universal coverage with the Federal government as the single payer. Proponents; Braun, Kunicinch, and Sharpton. Cost; over a Trillion per year at least. Needless to say, none of these candidates are anywhere near the front runners in the polls. Do these people even remember Hillary Clinton and the early ’90s? Under such a system costs would be contained via price controls, restrictions, and rationing and for all this reduced care most Americans will be hit with either higher taxes and/or higher consumer prices (in order to raise most of the trillions needed to pay universal health care many of these plans would target businesses and investments with massive tax increases and these costs would in turn be passed on to the consumer).

2. Universal coverage via employers. Proponent; Gephardt, who would mandate that all employers pay for health insurance for their employees. Employers would be able to deduct 60% of the costs of the insurance premiums (the 60% would also be for the self employed and for government workers). Requiring all employers to provide for some type of health insurance for their employees is a great idea but in it’s current form as proposed by Gephardt it is potentially the most disastrous as far as containing health care costs is concerned.

What he is essentially proposing is that we massively expand the same system that has effectively insulated patients from the real costs of health care, prevented any type of competition or market forces from controlling costs and allowed health care expenses and usage to get out of control in the first place (see my post on this issue)! Without any market forces or direct governmental restrictions to control costs, usage of health care resources would expand ad nauseum and ultimately bankrupt the system. Cost; $215,000,000,000.00 a year assuming that health care costs remain level (likely to be several hundred Billion above these estimates).

3. Expansion of current programs or new government programs. Proponents; Clark, Dean, Edwards, Kerry, Lieberman. Costs; Anywhere from about $50 to $100 billion a year. With minor differences most of these proposals would expand coverage for children, provide for more coverage for people in between jobs, and increase tax relief for employers providing health insurance coverage (though not as much as Gephardt’s plan).

What is the bottom line?

None of these plans would institute any meaningful market reforms that may help to control health care costs. They claim their plans would make health care “more affordable for all Americans” but it all amounts to little more than political slight of hand. Health care wouldn’t be made cheaper nor more affordable. The costs would just be shifted and spread around. Higher costs for employers would be passed off to consumers and the rest would be paid by taxpayers in one form or another.

The danger of many of these plans is that the more money they pour into the system the more they will stimulate health care usage and this will lead yet again to large cost increases. I would be willing to bet that any one of these plans to expand health care coverage will be costing two or three times as much as projected in the next few years alone.

Government, when it simply transfers money (e.g. Medicare), can face lower marketing and administrative costs than does a private insurance company. Or government can save money by simply getting out of the way. These cases aside, the only way government can save real resources on health care is to restrict access, typically through some form of rationing. See also my earlier post on who are the uninsured.

Which party is better for the stock market?

Democrats, it turns out, read Hal Varian on this question. Here is a summary of the data:

Professors Santa-Clara and Valkanov look at the excess market return – the difference between a broad index of stock prices (similar to the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index) and the three-month Treasury bill rate – between 1927 and 1998. The excess return measures how attractive stock investments are compared with completely safe investments like short-term T-bills.

Using this measure, they find that during those 72 years the stock market returned about 11 percent more a year under Democratic presidents and 2 percent more under Republicans – a striking difference.

This nine-percentage-point excess can be broken down further into an average 5.3 percent higher real return for the stock market and a 3.7 percent lower return for Treasury bills under Democratic administrations.

This regularity is harder to explain than you think, and simply defending Democrats or attacking Republicans will not do the trick. Remember, high stock market returns mean, not that things are good per se, but rather that things are better than people had expected.

I might have thought that people simply overestimate how bad Democratic Presidents will be. But no, the market does not appear to decline as the election of a Democrat approaches. Nor do changes in the risk premium seem to account for the patterns. Take a look at the original research.

Small companies, by the way, do especially well under Democrats:

One interesting finding is that although both large and small companies do better under Democratic administrations, small companies do especially well, while larger ones do only a little better. The return on the smallest 10 percent of traded companies is 21 percent higher during Democratic administrations, while the return on the largest 10 percent is only 7.7 percent greater.

Email if you have any good ideas. Maybe being unduly pessimistic also causes us to vote for Democrats, that is the best I can come up with. It is in fact the case that conservatives are happier, and more likely to believe that they are in control of their lives, than are liberals. Maybe we see similar patterns, not just in the cross-section, but also across time. When people feel bad, and out of control, stock prices fall too low, and those people act more like Democrats in the voting booth.