Results for “education” 2162 found

Education sentences to ponder

https://twitter.com/joshgreenman/status/1140758751420583936

How much of education is signaling? — yet again

The social and the private returns to education differ when education can increase productivity and also be used to signal productivity. We show how instrumental variables can be used to separately identify and estimate the social and private returns to education within the employer learning framework of Farber and Gibbons (1996) and Altonji and Pierret (2001). What an instrumental variable identifies depends crucially on whether the instrument is hidden from or observed by the employers. If the instrument is hidden, it identifies the private returns to education, but if the instrument is observed by employers, it identifies the social returns to education. Interestingly, however, among experienced workers the instrument identifies the social returns to education, regardless of whether or not it is hidden. We operationalize this approach using local variation in compulsory schooling laws across multiple cohorts in Norway. Our preferred estimates indicate that the social return to an additional year of education is 5%, and the private internal rate of return, aggregating the returns over the life-cycle, is 7.2%. Thus, 70% of the private returns to education can be attributed to education raising productivity and 30% to education signaling workers’ ability.

That is from a new NBER Working Paper by Gaurab Aryal, Manudeep Bhuller, and Fabian Lange. You can enter “education signaling” into the MR search function for much more on this ongoing debate.

Bloat Does Not Explain the Rising Cost of Education

In Why Are The Prices So D*mn High? Helland and I examine lower education, higher education and health care in-depth and we do a broader statistical analysis of 139 industries. Today, I will make a few points about education. First, costs in both lower and higher education are rising faster than inflation and have been doing so for a very long time. In 1950 the U.S. spent $2,311 per elementary and secondary public school student compared with $12,673 in 2013, over five times more (both figures in $2015). The rate of increase was fastest in the 1950s and 1960s–a point to which I will return later in this series.

College costs have also increased dramatically over time. For this book, we are interested in costs more than tuition because we want to know what society is giving up to produce education rather than who, in the first instance, is paying for it. Costs are considerably higher than tuition even today, although in recent years tuition has been catching up. Essentially students and their parents have been paying an increasing share of the increasing cost of higher education. Moreover, as with lower education, costs have been rising for a very long period of time.

I will take it as given that the explanation for higher costs isn’t higher quality. The evidence on tests scores is discussed in the book:

It is sometimes argued that how we teach has not changed but that what we teach has improved in quality. It is questionable whether studies of Shakespeare have improved, but there have been advances in biology, computer science, and physics that are taught today but were not in the past. However, these kinds of improvements cannot explain increases in cost. It is no more expensive to teach new theories than old. In a few fields, one might argue that lab equipment has improved, which it certainly has, but we know from figure 1 that goods in general have decreased in price. It is much cheaper today, for example, to equip a classroom with a computer than it was in the past.

The most popular explanation why the cost of education has increased is bloat. Elizabeth Warren and Chris Christie, for example, have both blamed climbing walls and lazy rivers for higher tuition costs. Paul Campos argues that the real reason college costs are growing is “the constant expansion of university administration.” Redundant administrators are also commonly blamed for rising public school costs.

The bloat theory is superficially plausible. The lazy rivers do exist! But the bloat theory requires longer and lazier rivers every year, which is less plausible. It’s also peculiar that the cost of education is rising in both lower and higher education and in public and private colleges despite very different competitive structures. Indeed, it’s suspicious that in higher education bloat is often blamed on competition–the “amenities arms race“–while in lower education bloat is often blamed on lack of competition! An all-purpose theory doesn’t explain much.

The bloat theory is superficially plausible. The lazy rivers do exist! But the bloat theory requires longer and lazier rivers every year, which is less plausible. It’s also peculiar that the cost of education is rising in both lower and higher education and in public and private colleges despite very different competitive structures. Indeed, it’s suspicious that in higher education bloat is often blamed on competition–the “amenities arms race“–while in lower education bloat is often blamed on lack of competition! An all-purpose theory doesn’t explain much.

More importantly, the data reject the bloat theory. Figure 8 shows spending shares in higher education. Contrary to the bloat theory, the administrative share of spending has not increased much in over thirty years. The research share, where you might expect to find higher lab costs, has fluctuated a little but also hasn’t risen much. The plant share which is where you might expect to find lazy rivers has even gone down a little, at least compared to the early 1980s.

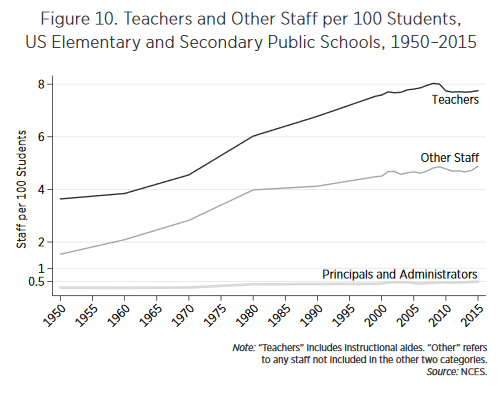

Nor is it true that administrators are taking over the public schools, see Figure 10.

Nor is it true that administrators are taking over the public schools, see Figure 10.

Compared with teachers and other staff, the number of principals and administrators is vanishingly small, only 0.4 per 100 students over the 1950–2015 period. It is true, if one looks closely, that the number of principals and administrators doubled between 1970 and 1980. It is unclear whether this is a real increase or a data artifact (we only have data for 1970 and 1980, not the years in between during this period). But because the base numbers are small, even a doubling cannot explain much. A bloated little toe cannot explain a 20-pound weight gain. Moreover, the increase in administrators was over by 1980, but expenditures kept growing.

If bloat doesn’t work, what is the explanation for higher costs in education? The explanation turns out to be simple: we are paying teachers (and faculty) more in real terms and we have hired more of them. It’s hard to get costs to fall when input prices and quantities are both rising and teachers are doing more or less the same job as in 1950.

We are not arguing, however, that teachers are overpaid!

Indeed, it is part of our theory that teachers are earning a normal wage for their level of skill and education. The evidence that teachers earn substantially above-market wages is slim. Teachers’ unions in public schools, for example, cannot explain decade-by-decade increases in teacher compensation. In fact, most estimates find that teachers’ unions raise the wage level by only approximately 5 percent. In other words, teachers’ unions can explain why teachers earn 5 percent more than similar workers in the private sector, but unions cannot explain why teachers’ wages increase over time.

If the case for unions as a cause of rising teacher compensation in public schools is weak, it is nonexistent for increased compensation for college faculty, for whom wage bargaining is done worker by worker with essentially no collective bargaining whatsoever.

A signal to where we are heading is this:

If increasing labor costs explain the increasing price of education but teachers are not overpaid relative to similar workers in other industries, then increasing labor costs must lead to higher prices in the education industry more than in other industries.

Read the whole thing. Next up, health care.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

Education sentences to ponder

More than 75 percent of online students enroll at an institution within 100 miles of their homes, according to recent research from The Learning House (and consistent across past surveys over time). A majority of online students visit campus to access services and support, or to attend events and in-person courses, in a true blending of online and in-person.

Here is a good Sean Gallagher survey on the rise of on-line degrees.

My musical self-education

Musick-er requests:

I’ve noticed that you tend to have pretty wide ranging tastes in music, and your recommendation on introduction to classical music was pretty spot-on. I’m wondering what training/expertise you have in music theory/aural skills?…As someone who is obviously very intelligent but not a musician (that I know of), I wonder how you interact with Bach or other master composers – what criteria do you listen for? What makes great works stand out from the merely good?

My history is this:

1. I learned how to play the guitar when I was twelve or so, and also figured out how a piano works.

2. I spent about six years studying jazz chords, American popular song, some classic rock, early acoustic blues and ragtime, Fahey/Kottke, and Bach. I also learned how to listen with a score, at least for guitar and piano pieces.

3. Later in life, I focused on trying to make sense of early to mid 20th century classical music and Indian classical music, both excellent entry points for many of the other difficult musical genres and styles. I tried to learn at least something about micro-tonal musics and ragas.

4. Starting in my thirties, I tried to develop a basic familiarity with world musics, not so much the European folkie stuff as those based on different conceptual principles, such as some of the Arab musics, Chinese music, and African musics including the Pygmies.

5. I cultivated “music mentors” to help me understand these musics. Overall this is not a very book-intensive endeavor, though you will enjoy reading accompanying biographies.

I am not saying that is the right path for everyone, but I found it very rewarding, including for my broader understanding of history.

To address one of the specific questions, I think of Bach-Stravinsky, classic rock, and Indian classical music (live only) as covering some of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements, with only cinema in the running for possible parity. Most of all just listen plenty, noting that the canonical opinions about what is best are actually pretty much on the mark.

Educational sentences to ponder

Of course, poor kids can still soar in school, and rich ones can flunk out, but few would deny that money is a powerful influence on people’s futures. Now, consider that household income explains just 7 percent of the variation in educational attainment, which is less than what genes can now account for. “Most social scientists wouldn’t do a study without accounting for socioeconomic status, even if that’s not what they’re interested in,” says Harden. The same ought to be true of our genes.

And:

“Education needs to start taking these developments very seriously,” says Kathryn Asbury from the University of York, who studies education and genetics. “Any factor that can explain 11 percent of the variance in how a child performs in school is very significant and needs to be carefully explored and understood.”

The researchers are to the point:

What policy lessons or practical advice do you draw from this study?

None whatsoever. Any practical response—individual or policy-level—to this or similar research would be extremely premature and unsupported by the science.

Here is the story, via Michelle Dawson. Here is the underlying paper, here are the FAQ.

Higher education update occasionally we innovate

To pay for his professional flight degree at Purdue University in Indiana, Andrew Hoyler had two choices. He could rely on loans and scholarships. Or he could cover some of the cost with an “income-share agreement” (ISA), a contract with Purdue to pay it a percentage of his earnings for a fixed period after graduation.

And:

Around a third of graduate education in America is now online, according to Richard Garrett of Eduventures, a consultancy. Many universities take a do-it-yourself approach, but the better-known ones tend to go into partnership with the OPMs. 2U, a ten-year-old startup, led the way, and has been followed into the business by, among others, Pearson, an educational publisher, and Coursera (which started off as a provider of MOOCs). Coursera joined up with UoI to create its online MBA programme.

Both are from The Economist.

Housing Costs Reduce the Return to Education

In normal times and places house prices are kept fairly close to construction costs by the ordinary processes of supply and demand. Average house prices didn’t rise much over the entire 20th century, for example. Even today, house prices are kept close to construction costs in most of the United States. But extreme supply restrictions in a small number of important places (San Francisco, San Jose, LA, New York, Boston etc.), have driven average prices well above any seen in the entire 20th century.

Over the last several decades high productivity industries have become more geographically concentrated. As a result, a substantial share of the productivity gains from technology, bio-tech and finance have gone not to producers but to non-productive landowners. High returns to land have meant lower returns to other factors of production.

The return to education, for example, has increased in the United States but it’s less well appreciated that in order to earn high wages college educated workers must increasingly live in expensive cities. One consequence is that the net college wage premium is not as large as it appears and inequality has been over-estimated. Remarkably Enrico Moretti (2013) estimates that 25% of the increase in the college wage premium between 1980 and 2000 was absorbed by higher housing costs. Moreover, since the big increases in housing costs have come after 2000, it’s very likely that an even larger share of the college wage premium today is being eaten by housing. High housing costs don’t simply redistribute wealth from workers to landowners. High housing costs reduce the return to education reducing the incentive to invest in education. Thus higher housing costs have reduced human capital and the number of skilled workers with potentially significant effects on growth.

Housing is eating the world.

Genes->Education->Social Mobility

Tens of thousands of studies correlate family socioeconomic status with later child outcomes like income, wealth and attainment and then claim the correlation is causal. Very few such studies control for genetics, although twin adoption studies suggest that genetics is important. Cheap genomic scanning, however, has made it possible to go beyond twin studies. A new paper, for example, looks at differences in education-associated genes between non-identical twins raised in the same family and they find that children with more education-associated genes tend to have greater educational attainment and higher income later in life. In other words, differences in child outcomes both across families and within the same family are in part driven by genetics.

Surprisingly, however, the authors also find evidence for “genetic nurture” the idea that parental genes drive child environment which drives outcomes. That’s surprising because it’s hard to find strong evidence for big environmental effects in adoption studies but here the authors can rely on more precise data. Specifically, the authors look at maternal education-associated genes that are NOT passed on to the children and yet they find that such genes are also correlated with important child outcomes (fyi, they only have maternal genes). So smart parents benefit children twice. First by passing on smart genes and second–even when they do not pass on smart genes–by passing on a smart environment. Previous studies missed the latter effect perhaps because they focused on rich parents rather than smart parents (the former being easier to measure). The authors suggest that by looking at how smart parents help kids without smart genes we may be able to figure out smart environments and generalize them to everyone. That strikes me as optimistic.

Here is the paper abstract:

A summary genetic measure, called a “polygenic score,” derived from a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of education can modestly predict a person’s educational and economic success. This prediction could signal a biological mechanism: Education-linked genetics could encode characteristics that help people get ahead in life. Alternatively, prediction could reflect social history: People from well-off families might stay well-off for social reasons, and these families might also look alike genetically. A key test to distinguish biological mechanism from social history is if people with higher education polygenic scores tend to climb the social ladder beyond their parents’ position. Upward mobility would indicate education-linked genetics encodes characteristics that foster success. We tested if education-linked polygenic scores predicted social mobility in >20,000 individuals in five longitudinal studies in the United States, Britain, and New Zealand. Participants with higher polygenic scores achieved more education and career success and accumulated more wealth. However, they also tended to come from better-off families. In the key test, participants with higher polygenic scores tended to be upwardly mobile compared with their parents. Moreover, in sibling-difference analysis, the sibling with the higher polygenic score was more upwardly mobile. Thus, education GWAS discoveries are not mere correlates of privilege; they influence social mobility within a life. Additional analyses revealed that a mother’s polygenic score predicted her child’s attainment over and above the child’s own polygenic score, suggesting parents’ genetics can also affect their children’s attainment through environmental pathways. Education GWAS discoveries affect socioeconomic attainment through influence on individuals’ family-of-origin environments and their social mobility.

You can find the appendix with the key results here. I find the lab style difficult to follow. The authors run regressions, for example, but you won’t find a regression equation followed by a table with all the results. Instead the regression is described in the appendix and then some coefficients, but by no means all, are presented later in the appendix.

Has the wage-education locus for women been worsening?

That question is the focus of some recent research by Chen Huang.

Women’s labor force participation rate has moved from 61% in 2000, to 57% today. It seems two-thirds of this change has been due to demographics, namely the aging of the adult female population. What about the rest? It seems that, relative to education levels, wages for women have not been rising since 2000:

I discover that the apparent increase in women’s real wages is more than accounted for by the large increase in women’s educational attainment. Once I condition on education, U.S. women’s real wages have not increased since 2000 and may even have decreased by a few percentage points. Thus, the locus of wage/education opportunities faced by U.S. women has not improved since 2000 and may have worsened. Viewed in that light, the LFPR decrease for women under age 55 becomes less surprising.

You can consider that another indicator of the Great Stagnation.

More on the Education Tax

In my post, The Education Tax Reduces Inequality and the Incentive to Work, I illustrated how the high cost of college combined with income based pricing have turned education pricing into a tax with potentially significant effects on work and savings incentives. David Henderson pointed me to a paper by Martin Feldstein in 1992, College Scholarship Rules and Private Saving which states the issues very well.

This paper examines the effect of existing college scholarship rules on the incentive to save. The analysis shows that families that are eligible for college scholarships face “education tax rates” on capital income of between 22 percent and 47 percent in addition to regular slate and federal income taxes. The scholarship rules also impose an annual tax on previously accumulated assets. Through the combination of the implied tax on capital income and the associated tax on previously accumulated assets, the scholarship rules that apply to a middle-income family reduce the value of an extra dollar of accumulated assets by 30 cents in four years. A similar family with two children who attend college in succession will see an initial dollar of assets reduced to 50 cents. Such capital levies of 30 to 50 percent are a strong incentive not to save for college expenses but to rely instead on financial assistance and even on regular market borrowing, Moreover, since any funds saved for retirement are also subject to these education capital levies. the scholarship rules discourage retirement saving as well as saving for education. The empirical analysis developed here, based on the 1986 Survey of Consumer Finances, implies that these incentives do have a powerful effect on the actual accumulation of financial assets. More specifically, the estimated parameter values imply that the scholarship rules induce a typical household with a head aged 45 years old, with two precollege children, and with income of $40,000 a year to reduce accumulated financial assets by $23,124 approximately 50 percent of what would have been accumulated without the adverse effect of the scholarship rules.

Dick and Edlin made a similar point in 1997 but, as far as I can tell, there have been only a handful of papers on this issue since that time. The cost of college, however, is about twice as high today as in the 1980s and price discrimination is much more extensive so the effects are likely larger today.

The Education Tax Reduces Inequality and the Incentive to Work

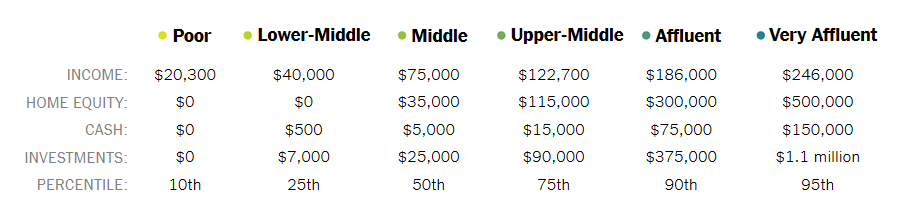

At the NYTimes David Leonhardt breaks families down into six income classes from the poor to the very affluent, defined as follows:

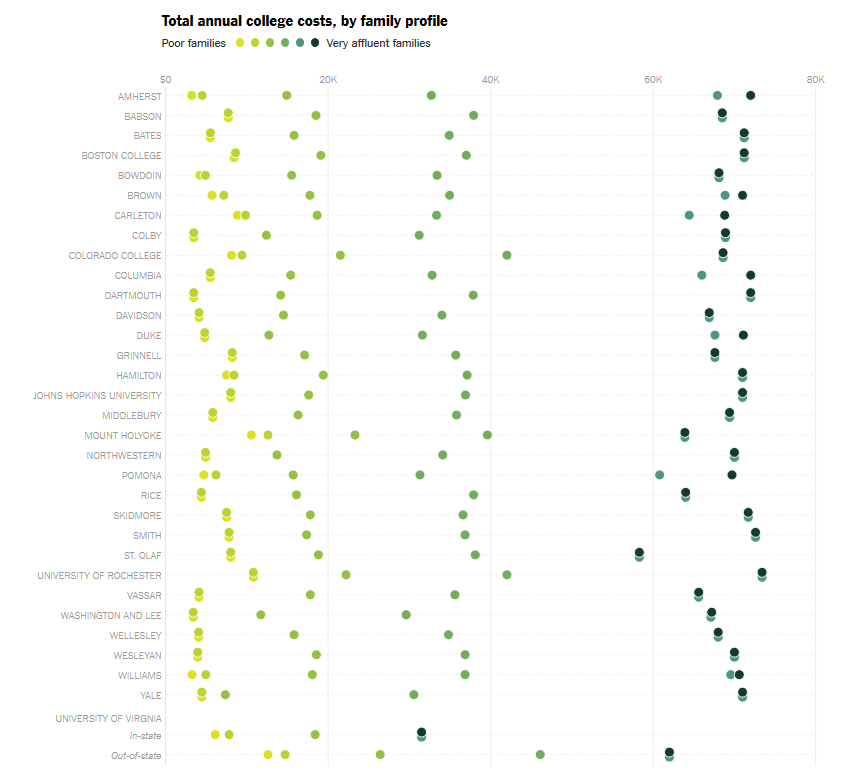

Using a tuition calculator he then estimates tuition (including room and board) by income class at 32 colleges and universities (see below–the darker dots indicate the richer income classes). At many private colleges and universities it is not unusual for some students to be paying $70,000 per year while others pay less than $5,000, for exactly the same education. (Tyler and I provide some similar data on college price discrimination in Modern Principles.) Leonhardt’s point is that a poor student can afford an expensive education and might actually save money by going to an elite private university rather than to a state college.

Price discrimination in education has two other, less recognized, consequences. It reduces income inequality and it reduces the incentive to work. If every firm charged twice as much to someone who earned twice as much, there would no consumption inequality despite high measured income inequality. The rich don’t pay more than the poor when they buy the same basket of goods at the grocery store but they do pay much more for the same education.The Affluent pay approximately $70 thousand for education at the colleges Leonhardt examines while the Upper-Middle pay about half that. The effect on inequality is significant for families with kids in college. An Affluent person is 52% richer than an Upper-Middle income person (186/122=1.52) but an Affluent person with a kid in college is only 33% richer than an Upper-Middle income person with a kid in college (((186-70)/(122-35)=1.33). Shockingly, an Affluent person with two kids in college is actually poorer than an Upper-Middle income person with two kids in college! ((186-140)/(122-70)=0.88.

Under income-based pricing the education tax becomes an income tax with all the negative aspects of income taxes on behavior such as diminished work incentives. Let’s take a closer look at an Upper-Middle income parent earning $122 thousand per year. If this parent gets a promotion or takes on extra work that bumps their salary by $64 thousand, they move from being Upper-Middle income to Affluent. At least on paper. At an income of $122 thousand the parent will be paying approximately $35 thousand to send their child to college but at $186 thousand they will have to pay $70 thousand for the same college so the increase in salary of $64 thousand is an effective increase of only $29 thousand. If the Upper-Middle income parent has two children in college, earning more money actually results in a net loss. For an Upper-Middle income family with two kids spaced in age a few years apart the education tax could be a very severe work disincentive for up to a decade.

The education tax is a peculiar tax as it is often paid to private organizations rather than to the government but it is still a tax and for those of Upper-Middle income the education tax is a very significant tax.

The consequences of the education tax on inequality and work incentives are neither well studied nor well understood.

Against Foreign Language Education

Bryan Caplan is on fire in this excellent podcast with Robert Wiblin of 80,000 hours:

Bryan Caplan: In the U.S. I’ve heard so many times – I learned Latin and it really improved my score on the SAT because of all the Latin roots of the English vocabulary words. How about you learn some English vocabulary words, wouldn’t that be a little easier?

Robert Wiblin: I’m just… I’m pulling out my hair here.

Bryan Caplan: Well if you wanna pull out your hair a little bit more. Out of all my ultra moderate reforms that I suggested, the one that I stand behind more strongly than any other is abolishing foreign language requirements in the United States. Because there, we’ve got a bunch of facts, which are: hardly any jobs use foreign languages, it takes a lot of time to get any good. And furthermore, in this book I’m able to go and snap together a bunch of pieces of data to show that virtually zero Americans claim to… even claim to speak a foreign language very well in school.

So I say, look, even if it did have these big payoffs, the system is just a waste of time, and people spend years doing it for nothing. And even here, I just run against a brick wall and people say, well in that case we should just improve the teaching of the foreign language.

Well, how about you do that and then get back to me, but continuing to fund the thing that we have, this is garbage!

And again, Washington state from what I understand, now allows kids to use a computer language in place of foreign language. Like, why not do that? Then it’s like, “No, no we need to do both.” People don’t have an unlimited amount of time, and shouldn’t teenagers be able to have a frigging childhood! Like how much of their childhood do you want to destroy with jumping through these stupid hoops?

As someone who was educated in Canada I can attest to the waste of much foreign language instruction. I had at least 6 years of instruction in French but my French today is perhaps on par with two or three days worth of Berlitz and that mostly because I’ve been to France a few times. For reasons of national unity and ideology, almost all Canadians have years of French instruction but most of the little of what is learned is quickly forgotten. Looking at bilingual cereal boxes is not enough to maintain skill. If you are French in Quebec there are good reasons to learn English but outside of Quebec there are few reasons to learn French. As a result, the large majority of bilingual speakers are native French speakers (plus a few budding politicians). Indeed, among the Canadians who speak English there could well be more Hindi or Chinese bilinguists than French bilinguists.

Don’t make the mistake of arguing that knowing a second language has many benefits. The point is that foreign language instruction in schools doesn’t teach a second language.

Addendum: And don’t forget this.

Does higher education change non-cognitive skills?

There is a new study on this very important question:

We examine the effect of university education on students’ non-cognitive skills (NCS) using high-quality Australian longitudinal data. To isolate the skill-building effects of tertiary education, we follow the education decisions and NCS—proxied by the Big Five personality traits—of 575 adolescents over eight years. Estimating a standard skill production function, we demonstrate a robust positive relationship between university education and extraversion, and agreeableness for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The effects are likely to operate through exposure to university life rather than through degree-specific curricula or university-specific teaching quality. As extraversion and agreeableness are associated with socially beneficial behaviours, we propose that university education may have important non-market returns.

That is from Sonja C. Kassenboehmer, Felix Leung, and Stefanie Schurer in the new Oxford Economic Papers. Here is a much older, non-gated version.

These results seem broadly consistent with the 1960s “schooling of society,” conformist, Marxian critiques of education. It is striking that higher education does not have more of a notable, measurable impact on either openness or conscientiousness.

In passing, I would like to note that I am not crazy about the term “non-cognitive” in this context.

What if you combined Robin Hanson and German higher education?

Students in Germany rated their curriculum, teaching and job prospects more highly when their universities were labeled “excellent” by the government — even though the award was unrelated to teaching, according to new research.

But this next sentence does not follow:

The results cast further doubt on the reliability of student satisfaction scores, a co-author of the study said.

Here is the full story by David Matthews.