Results for “education signaling” 84 found

The Parent Trap–Review of Hilger

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Hilger argues that the problems of poverty, pathology and inequality that bedevil the United States are not primarily due to poor schools, discrimination, or low incomes per se. The primary cause is parents: parents who are unable to teach their children the skills that are necessary to succeed in the modern world. Since parents can’t teach the necessary skills, Hilger calls for the state to take their place with a dramatic expansion of not just child care but collective parenting.

Let’s unpack some details. Begin with schooling. It’s very common to bemoan the state of schools in the “inner city” or to complain about “local financing” which supposedly guarantees that poor counties will have underfunded schools. All of this, however, is decades out-of-date.

A hundred years ago there really were massive public-school resource gaps by class and race. These days, however, state and federal spending play a larger role than local property tax revenue and distribute educational resources more progressively….In fact, when we include federal aid, 42 states spent more on poor school districts than on rich school districts in 2012. The same pattern holds between schools within districts

….The highest spending districts are large urban centers such as New York City, Boston and Baltimore. These cities spend large sums to educate rich and poor children alike. p. 10-11

Hilger is correct. No matter what you saw on The Wire, Baltimore spends more than sixteen thousand dollars per student, among the highest in the nation in large school districts and above average for the nation as a whole. Public schools are quite egalitarian in funding with any bias running towards more funding for poorer districts.

Schools, Hilger writes are “actually the smallest and most equalizing part of a much larger skill-building system.” The real problem, says Hilger, are parents.

But what about discrimination? When it comes to wage discrimination, Hilger is brutally honest:

If we compare individuals with similar cognitive test scores, Black college graduates earn higher wages than white college graduates. Studies that don’t control for test score differences but examine earnings gaps within specific professions—lawyers, physicians, nurses, engineers, scientists—tend to find Black workers earn zero to 10 percent less than white workers. These gaps could reflect discrimination, unmeasured skill differences, or other factors such as geography. In any case, such gaps are small compared to the 50 percent overall Black-white earnings gap and reinforce the idea that closing skills gaps would go a long way toward closing income gaps.

Hilger argues that racism does play an important role in explaining Black-white wage differentials but it’s the historical racism that made black parents less skilled and less able to pass on skills to their children. In the twentieth century, Asians, Hilger argues, were discriminated against in the United States at least much as Black Americans. But the Asians that came to the United States had high skills while the legacy of slavery meant that Black Americans began with low skills. Asians, therefore, were better able to overcome discrimination. The success of Nigerians and Jamaican immigrants in the United States also speaks to this point. (Long time readers may recall that in 2016 I dubbed Hilger’s paper on Asian Americans and Black Americans the Politically Incorrect Paper of the Year .)

Parental investment is surely important but Hilger overstates his case. He writes as if poorer parents have neither the abilities nor the time to teach their children while richer, better educated parents simply invest lots of hours and money imbuing their children with skills:

…the enormous variation in parents’ own academic skills has big implications for kids because we also demand that parents try to be tutors. During normal times, parents in America spend an average of six hours per week helping—or trying to help—their kids with school work. Six hours per week is more than K12 math and English teachers get with children…good tutoring by parents for six hours a week, every week, year after year of childhood could raise children’s future earnings by as much as $300,000.

The data on the effectiveness of SAT test-prep suggests that these efforts are not nearly so effective as Hilger argues. The parental investment story also doesn’t fit my experience. I didn’t spend six hours a week helping my kids with their homework. I doubt most parents do. I simply assumed my kids would do their work. I do recall that we signed my kids up for tutoring at Kumon, the Japanese math education center. My kids would complain bitterly when we took them for drill on the weekend. It was mostly filling out rote forms and my kids would hide or bury their drill sheets so we were always behind. Driving my kids to the Kumon center, monitoring them. and forcing them to do the work when they rebelled like longshoreman on work-to-rule was time consuming and it was ruining our weekends. I felt guilty, but after a while, my wife and I gave up. Today one of my sons is a civil engineer and the other is a math and economics major at UVA.

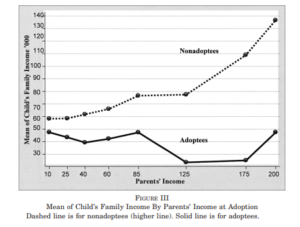

Hilger has an answer to this line of objection, or at least he says he does, but to my mind it’s a very odd answer. He argues, relying heavily on Sacerdote, that adoption studies show that more skilled parents result in more skilled kids. I find that answer odd because my reading of Sacerdote is that the effect of parents are small after you control for genetics—this is, as Hilger acknowledges, the conventional wisdom among psychologists. (See Caplan for an excellent review of the literature). It is true that Sacerdote plays up the effect of parents, but it looks small to me. Here is the effect of the adopted mother’s maternal education on the child’s education.

As you can see there is an effect but it is almost all from the mother going from having less than a high school education to graduating high school (11 to 12 years). In contrast, the mother can move from graduating high school to having a PhD and there is very little change in the education level of an adoptee. Note, however, that the effect on non-adoptees, i.e. biological children, is much larger throughout the entire range which suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

I am not surprised that there is some effect of parental education on child’s education because going to college is in part a cultural issue. Parents can influence cultural aspects of their children’s identity such as whether a child grows up up nominally Catholic, Mormon, or Hindu but they have relatively little effect on child religiosity, let alone personality or IQ. I think that a large fraction of the college wage premium is signaling (50% is a moderate estimate, Caplan thinks 90% is closer to the truth), so I am also not overly excited about college attendance as a marker of success.

The effect of parental income on the income of child adoptees is even more dramatic than on education—which is to say negligible. The income of the adopted parents has zero effect (!) on child’s income even as parent’s income varies by a factor of 20! The only correlation is with non-adoptee income—which again suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

At this point in the book, it was almost inevitable that we were going to get yet another paean to the Perry Preschool Project and indeed Hilger waxes enthusiastically about Perry. Seriously? The Perry Preschool project started in the 1960s and had just 123 participants (58 in treatment and 65 in control!). There are more papers about the Perry Preschool project than there were participants. I am jaded.

Aside from the small sample size, the project had imperfect randomization and missing data and most importantly limited external validity. The Perry Preschool project treated a small group of disadvantaged African American children with low-IQs (IQs of 70-85 were part of the selection criteria). The treatment is usually described as “active learning pre-school” but it was more intrusive than that. Every week counselors would go to the homes of the kids to teach the parents (mostly mothers) how to raise their children. The training was important to the program. Indeed, Hilger notes, without sense of irony, that “facilitating greater skill growth in low-income children was so complicated that it required home visitors with advanced postsecondary degrees.” (p. 89). And what were the results?

The results were good! (Heckman et al. 2010, Belfield et al. 2006). But in the popular literature the impression one gets is that the program took a bunch of disadvantaged kids and helped them read and write, making them more middle-class and successful. Some of that happened but the big gains actually happened because the participants, especially the boys, were so socially dangerous and destructive that even a bit of normalization made life substantially better for everyone else. In particular 82% of the treated group of 33 males had been arrested by age 40, including for one murder, 4 rapes, 8 robberies, 11 assaults and 14 burglaries. The control group were worse. In the control group of 39 males there were 2 murders. Indeed the reduction of one murder in the treatment group accounts for a significant benefit of the entire Perry PreSchool project.

Hilger, to his credit, is reasonably clear that what is really needed is an intensive program for disadvantaged African Americans, especially males. In a stunning sentence he writes:

The more we rely on families rather than professionals to build skills in children, the tighter we link people’s current prospects to the prospects of their ancestors. p. 134

But he soon forgets or papers over the context of the Perry Preschool project and like everyone else in the literature uses this to support a national program for which there is no external validity. It’s hard to believe, given the lack of external validity, but Heckman et al. (2010) only exagerate mildly when they write:

The economic case for expanding preschool education for disadvantaged children is largely based on evidence from the HighScope Perry Preschool Program…

Hilger’s case for the difficulty of parenting is well taken—the FAFSA was a nightmare that taxed two PhDs in my family. But the bottom line is that most parents do just fine. Moreover, it’s shocking that in recounting the difficulties of parenting Hilger says hardly one word about an obvious factor which makes parenting more than twice as hard. Namely, single parenting. I was a single parent. Once for a whole week. Don’t do it. Get married, stay married. Perhaps Hilger didn’t want to appear to be too conservative.

Instead of recommending marriage and small targeted programs and more experiments, Hilger goes full Plato.

What would it look like if we [asked]…less not more of parents? It would look like professional experts managing more than the meagre 10 percent of children’s time currently managed by our public K12 system—much more. p. 184

And why should we do this? Because we are all part slaves and part slave-owners on a giant collective farm:

As fellow citizens who benefit from tax revenue, we all—even those of us without children—collectively own about 30 percent of any additional income other people’s children wind up earning. p. 197

Ugh. We own ourselves, not one another. Society isn’t about maximizing the collective it’s about free individuals coming together to produce rules so that we can enjoy the benefits of collective action while still living in a diverse society that respects individual rights, beliefs, and ways of living.

I told you I hated parts of The Parent Trap but Hilger has written an interesting and challenging book and he is mostly right that neither schooling nor labor market discrimination play a major role in the black-white wage gap. Hilger is probably also right that we spend too much on the elderly relative to the young. The idea of greater state involvement in the raising of children is on the table today in a way it hasn’t been for some time. See also Dana Susskind’s recent book Parent Nation. Changes on the margin may be warranted. Nevertheless, I stand with Aristotle and not Plato in thinking that raising children is better done by parents than by the state.

Against credentialism

That is the theme of my latest Bloomberg column, induced by a timely tweet by Conor Sen. It turns out the state of Maryland is abolishing the four-year college degree requirement for many state jobs. In Missour, neither the governor nor the lieutenant governor have a four=year college degree, so perhaps they should follow suit?

From the column, here is one bit:

On average, more education probably does correlate with better job performance — but there are a lot of exceptions. If U.S. society wants to boost opportunity for everyone, it needs to work harder to spot those exceptions and act on that knowledge. In a world where so much information and so many diverse forms of certification are available, there are far better ways to assess a candidate than asking the binary question of whether they have a four-year degree.

This move against credentialism is all the more imperative due to the rise of technology. Many of the top names in tech or crypto are dropouts and do not have degrees. To be sure, those are not the kind of people the Maryland state government is likely to be recruiting. But there are numerous people in tech, lower on the salary scale, who have not invested much in formal credentials, in part because they failed to see their professional relevance. For many tech jobs, a personal GitHub page is far more important.

From these passages you also can see why the credentialism critique is slightly different from some of the more radical critiques of educational signaling. In my view, education does causally improve performance on a lot of jobs, at least on average, through more or less the traditional channels. Still, treatment effect variances can be high, and very often we can do better with more finely grained assessments of individual talent, rather than taking a four year degree to be a binary yes/no qualification. In many cases, for instance, would you rather not hire some with a military background? The bottom line is that you can achieve a superior allocation of talent, and cut back on signaling costs, even if you think signaling is a clearly present but not dominant force behind the demand for higher education.

Where I differ from Bryan Caplan’s *Labor Econ Versus the World*

One thing I liked about reading this book is I was able to narrow down my disagreements with Bryan to a smaller number of dimensions. And to be clear, I agree with a great deal of what is in this book, but that does not make for an interesting blog post. So let’s focus on where we differ. One point of disagreement surfaces when Bryan writes:

Tenet #6: Racial and gender discrimination remains a serious problem, and without government regulation, would still be rampant.

Critique: Unless government requires discrimination, market forces make it a marginal issue at most. Large group differences persist because groups differ largely in productivity.

I would instead stress that most of the inequity occurs upstream of labor markets, through the medium of culture. It is simply much harder to be born in the ghetto! I am fine with not calling this “discrimination,” and indeed I do not myself use the word that way. Still, it is a significant inequity, and it is at least an important a lesson about labor markets as what Bryan presents to you.

But you won’t find much consideration of it in Bryan’s book. The real problems in labor markets arise when “the cultural upstream” intersects with other social institutions in problematic ways. To give a simple example, Princeton kept Jews out for a long time, and that was not because of the government. Or Princeton voted to admit women only in 1969, again not the government. What about Major League Baseball before Jackie Robinson or even for a long while after? Much of Jim Crow was governmental, but so much of it wasn’t. There are many such examples, and I don’t see that Bryan deals with them. And they have materially affected both people’s lives and their labor market histories, covering many millions of lives, arguably billions.

Or, the Indian government takes some steps to remedy caste inequalities, but fundamentally the caste system remains, for whatever reasons. Again, this kind of cultural upstream isn’t much on Bryan’s radar screen. (I have another theory that this neglect of culture is because of Bryan’s unusual theory of free will, through which moral blame has to be assigned to individual choosers, but that will have to wait for another day!)

We can go beyond the discrimination topic and still see that Bryan is not paying enough attention to what is upstream of labor markets, or to how culture shapes human decisions.

Bryan for instance advocates open borders (for all countries?). I think that would be cultural and political suicide, most of all for smaller countries, but for the United States too. You would get fascism first, if anything. I do however favor boosting (pre-Covid) immigration flows into the United States by something like 3x. So in the broader scheme of things I am very pro-immigration. I just think there are cultural limits to what a polity can absorb at what speed.

If you consider Bryan on education, he believes most of higher education is signaling. In contrast, I see higher education as giving its recipients the proper cultural background to participate in labor markets at higher productivity levels. I once wrote an extensive blog post on this. That is how higher education can be productive, while most of your classes seem like a waste of time.

On poverty, Bryan puts forward a formula of a) finish high school, b) get a full time job, and c) get married before you have children. All good advice! But I find that to be nearly tautologous as an explanation of poverty. To me, the deeper and more important is why so many cultures have evolved to make those apparent “no brainer” choices so difficult for so many individuals. Again, I think Bryan is neglecting the cultural factors upstream of labor markets and in this case also marriage markets. One simple question is why some cultures don’t produce enough men worth marrying, but that is hardly the only issue on the table here.

More generally, I believe that once you incorporate these messy “cultural upstream” issues, much of labor economics becomes more complicated than Bryan wishes to acknowledge. Much more complicated.

I should stress that Bryan’s book is nonetheless a very good way to learn economic reasoning, and a wonderful tonic against a lot of the self-righteous, thoughtless mood affiliation you will see on labor markets, even coming from professional economists.

I will remind that you can buy Bryan’s book here, and at a very favorable price point.

*Labor Econ Versus the World*

The author is Bryan Caplan and the subtitle is Essays on the World’s Greatest Market. It is a collection of his best blog posts on labor markets over the last fifteen years or so. A Bryan blog post from 2015 gives a good overview of much of the book, which you can read as pushback against a lot of doctrines held by other people, including the mainstream:

What are these “central tenets of our secular religion” and what’s wrong with them?

Tenet #1: The main reason today’s workers have a decent standard of living is that government passed a bunch of laws protecting them.

Critique: High worker productivity plus competition between employers is the real reason today’s workers have a decent standard of living. In fact, “pro-worker” laws have dire negative side effects for workers, especially unemployment.

Tenet #2: Strict regulation of immigration, especially low-skilled immigration, prevents poverty and inequality.

Critique: Immigration restrictions massively increase the poverty and inequality of the world – and make the average American poorer in the process. Specialization and trade are fountains of wealth, and immigration is just specialization and trade in labor.

Tenet #3: In the modern economy, nothing is more important than education.

Critique: After making obvious corrections for pre-existing ability, completion probability, and such, the return to education is pretty good for strong students, but mediocre or worse for weak students.

Tenet #4: The modern welfare state strikes a wise balance between compassion and efficiency.

Critique: The welfare state primarily helps the old, not the poor – and 19th-century open immigration did far more for the absolutely poor than the welfare state ever has.

Tenet #5: Increasing education levels is good for society.

Critique: Education is mostly signaling; increasing education is a recipe for credential inflation, not prosperity.

Tenet #6: Racial and gender discrimination remains a serious problem, and without government regulation, would still be rampant.

Critique: Unless government requires discrimination, market forces make it a marginal issue at most. Large group differences persist because groups differ largely in productivity.

Tenet #7: Men have treated women poorly throughout history, and it’s only thanks to feminism that anything’s improved.

Critique: While women in the pre-modern era lived hard lives, so did men. The mating market led to poor outcomes for women because men had very little to offer. Economic growth plus competition in labor and mating markets, not feminism, is the main reason women’s lives improved.

Tenet #8: Overpopulation is a terrible social problem.

Critique: The positive externalities of population – especially idea externalities – far outweigh the negative. Reducing population to help the environment is using a sword to kill a mosquito.

Yes, I’m well-aware that most labor economics classes either neglect these points, or strive for “balance.” But as far as I’m concerned, most labor economists just aren’t doing their job. Their lingering faith in our society’s secular religion clouds their judgment – and prevents them from enlightening their students and laying the groundwork for a better future.

I will say this: Labor Econ Versus the World, while not written as a book per se, still is the best free market book on labor economics I know of. And it is very reasonably priced. I agree with much of what is in this book, but by no means all of it. I’ll consider my differences with it in a separate blog post, to come tomorrow.

David Card on the return to schooling

Card is best known amongst intellectuals for his minimum wage work, but he also has been central in estimating the returns to higher education, using superior methods. In particular, he has induced many economists to downgrade the import of the signaling model of education. Here is one excerpt from his Econometrica paper, appropriately entitled “Estimating the Return to Schooling: Progress on Some Persistent Econometric Problems:

A review of studies that have used compulsory schooling laws, differences in the accessibility of schools, and similar features as instrumental variables for completed education, reveals that the resulting estimates of the return to schooling are typically as

big or bigger than the corresponding ordinary least squares estimates. One interpretation of this finding is that marginal returns to education among the low-education subgroups typically affected by supply-side innovations tend to be relatively high, reflecting their high marginal costs of schooling, rather than low ability that limits their return to education.

The empirical problem arises of course because intrinsic talent and degree of schooling are highly correlated, so the investigator needs some recourse to superior identification. How can you tell if apparent returns to schooling simply reflect a higher talented cohort in the first place? So you might for instance look for an exogenous change to compulsory schooling laws that affects some children but not others (a few of those have come in the Nordic countries). That likely will be uncorrelated with child talent, and so it will help you separate out the true causal return to additional schooling, because you can measure whether the kids with that extra year end up earning more, controlling for other relevant variables of course. And see Alex’s discussion of the Angrist and Card paper on similar questions.

See also Card’s survey of this entire field, written for Handbook of Labor Economics. One impressive feature of these pieces is they show how many disparate methods of measurement all point toward a broadly common conclusion. Whether or not you agree, these papers have been extremely influential, and they are one reason why Claudia Goldin, in my recent CWT with her, asserted that very little of higher education was about the signaling premium.

My Conversation with the excellent Claudia Goldin

Here is the transcript and audio. Here is part of the CWT summary:

Claudia joined Tyler to discuss the rise of female billionaires in China, why the US gender earnings gap expanded in recent years, what’s behind falling marriage rates for those without a college degree, why the wage gap flips for Black women versus Black men, theoretical approaches for modeling intersectionality, gender ratios in economics, why she’s skeptical about happiness research, how the New York Times wedding announcement page has evolved, the problems with for-profit education, the value of an Ivy League degree, whether a Coasian solution existed to prevent the Civil War, which Americans were most likely to be anti-immigrant in the 1920s, her forthcoming work on Lanham schools, and more.

Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: If you look at a school, say, like Duke or Emory, is it a long-run problem that if they admit people on their merits, there’ll be too many women in the school relative to men, and some kind of affirmative action will be needed for the males?

GOLDIN: These are private institutions, and they can generally accept whom they would like to accept for various reasons of diversity.

COWEN: Should they do that? Or should they just get in 76 percent women, say?

GOLDIN: I’m brought back to the original issues that were raised by a small number of liberal arts colleges and universities in the ’50s and the ’60s about why they should become coeducational institutions.

Those reasons were that their marginal student was not going to Princeton but going to Harvard, not going to Princeton but going to Penn, not going to Princeton but going to Cornell, because that student wanted an education that was more balanced in terms of what the world would look like when they got out. And that more balanced, then, was not necessarily Blacks, Hispanics, and Jews, but the one major thing that was missing from Princeton and Yale and Dartmouth and Amherst and Wesleyan and a whole bunch of places was women.

Those institutions, in a process that I’ve described in the origins of coeducation, led these institutions to move in the direction of accepting more women. Now what’s going through your mind, I think, is, “Yes, but they weren’t lowering quality. In fact, they were increasing quality.” Diversity, in any dimension, can be thought of as a plus for everyone.

It was about 10 years ago that some dean in a small liberal arts college in the Midwest admitted to the fact that they were accepting men with lower SAT, ACT, and grade point averages to increase diversity.

COWEN: Men, probably, are not less intelligent than women, on average. What’s the pipeline problem? Is it too much homework and too many extracurriculars in high school or something else? Where are we failing our young boys?

GOLDIN: We can go back to as early as we have data on high schools and know that girls attended high schools, graduated from high schools at far, far greater numbers than boys. If there is an issue here, it’s certainly not extracurriculars. It may have to do with what’s going on in your cells and this difference between this Y and this double X.

COWEN: The value of an Ivy League degree — what percentage of that value do you think comes from signaling as opposed to learning?

GOLDIN: Very little. I think that it’s not signaling. It’s probably networks.

Self-recommending…

Paul Milgrom, Nobel Laureate

Most of all this is a game theory prize and an economics of information prize, including game theory and asymmetric information. Much of the work has had applications to auctions and finance. Basically Milgrom was the most important theorist of the 1980s, during the high point of economic theory and its influence.

Here is Milgrom’s (very useful and detailed) Wikipedia page. Most of his career he has been associated with Stanford University, with one stint at Yale for a few years. Here is Milgrom on scholar.google.com. A very good choice and widely anticipated, in the best sense of that term. Here is his YouTube presence. Here is his home page.

Milgrom, working with Nancy Stokey, developed what is called the “no trade” theorem, namely the conditions under which market participants will not wish to trade with each other. Obviously if someone wants to trade with you, you have to wonder — what does he/she know that I do not? Under most reasonable assumptions, it is hard to generate a high level of trading volume, and that has remained a puzzle in theories of finance and asset pricing. People are still working on this problem, and of course it relates to work by Nobel Laureate Robert Aumann on when people should rationally disagree with each other.

Building on this no-trade result, Milgrom wrote a seminal piece with Lawrence Glosten on bid-ask spread. What determines bid-ask spread in securities markets? It is the risk that the person you are trading with might know more than you do. You will trade with them only when the price is somewhat more advantageous to you, so markets with higher degrees of asymmetric information will have higher bid-ask spreads. This is Milgrom’s most widely cited paper and it is personally my favorite piece of his, it had a real impact on me when I read it. You can see that the themes of common knowledge and asymmetric information, so important for the auctions work, already are rampant.

Alex will tell you more about auctions, but Milgrom working with Wilson has designed some auctions in a significant way, see Wikipedia:

Milgrom and his thesis advisor Robert B. Wilson designed the auction protocol the FCC uses to determine which phone company gets what cellular frequencies. Milgrom also led the team that designed the 2016-17 incentive auction, which was a two-sided auction to reallocate radio frequencies from TV broadcast to wireless broadband uses.

Here is Milgrom’s 277-page book on putting auction theory to practical use. Here is his highly readable JEP survey article on auctions and bidding, for an introduction to Milgrom’s prize maybe start there?

Here is Milgrom’s main theoretical piece on auctions, dating from Econometrica 1982 and co-authored with Robert J. Weber. it compared the revenue properties of different auctions and showed that under risk-neutrality a second-price auction would yield the highest price. Also returning to the theme of imperfect information and bid-ask spread, it showed that an expert appraisal would make bidders more eager to bid and thus raise the expected price. I think of Milgrom’s work as having very consistent strands.

With Bengt Holmstrom, also a Nobel winner, Milgrom wrote on principal-agent theory with multiple tasks, basically trying to explain why explicit workplace incentives and bonuses are not used more widely. Simple linear incentives can be optimal because they do not distort the allocation of effort across tasks so much, and it turned out that the multi-task principal agent problem was quite different from the single-task problem.

People used to think that John Roberts would be a co-winner, based on the famous Milgrom and Roberts paper on entry deterrence. Basically incumbent monopolists can signal their cost advantage by making costly choices and thereby scare away potential entrants. And the incumbent wishes to be tough with early entrants to signal to later entrants that they better had stay away. In essence, this paper was viewed as a major rebuttal to the Chicago School economists, who had argued that predatory behavior from incumbents typically was costly, irratoinal, and would not persist.

The absence of Roberts’s name on this award indicates a nudge in the direction of auction design and away from game theory a bit — the Nobel Committee just loves mechanism design!

That said, it is worth noting that the work of Milgrom and co-authors intellectually dominated the 1980s and can be identified with the peak of influence of game theory at that period of time. (Since then empirical economics has become more prominent in relative terms.)

Milgrom and Roberts also published a once-famous paper on supermodular games in 1990. I’ve never read it, but I think it has something to do with the possible bounding of strategies in complex settings, but based on general principles. This was in turn an attempt to make game theory more general. I am not sure it succeeded.

Milgrom and Roberts also produced a well-known paper finding the possible equilibria in a signaling model of advertising.

Milgrom and Roberts also wrote a series of papers on rent-seeking and “influence activities” within firms. It always seemed to me this was his underrated work and it deserved more attention. Among other things, this work shows how hard it is to limit internal rent-seeking by financial incentives (which in fact can make the problem worse), and you will see this relates to Milgrom’s broader work on multi-task principal-agent problems.

Milgrom also has a famous paper with Kreps, Wilson, and Roberts, so maybe Kreps isn’t going to win either. They show how a multi-period prisoner’s dilemma might sustain cooperating rather than “Finking” if there is asymmetric information about types and behavior. This paper increased estimates of the stability of tit-for-tat strategies, if only because with uncertainty you might end up in a highly rewarding loop of ongoing cooperation. This combination of authors is referred to as the “Gang of Four,” given their common interests at the time and some common ties to Stanford. You will note it is really Milgrom (and co-authors) who put Stanford economics on the map, following on the Kenneth Arrow era (when Stanford was not quite yet a truly top department).

Not what he is famous for, but here is Milgrom’s paper with Roberts trying to rationalize some of the key features of modern manufacturing. If nothing else, this shows the breadth of his interests and how he tries to apply game theory generally. One question they consider is why modern manufacturing has moved so strongly in the direction of greater flexibility.

Milgrom also has a 1990 piece with North and Weingast on the medieval merchant guilds and the economics of reputation, showing his more applied side. In essence the Law Merchant served as a multilateral reputation mechanism and enforced cooperation. Here is a 1994 follow-up. This work paved the way for later work by Avner Greif on related themes.

Another undervalued Milgrom piece is with Sharon Oster (mother of Emily Oster), or try this link for it. Here is the abstract:

The Invisibility Hypothesis holds that the job skills of disadvantaged workers are not easily discovered by potential new employers, but that promotion enhances visibility and alleviates this problem. Then, at a competitive labor market equilibrium, firms profit by hiding talented disadvantaged workers in low-level jobs.Consequently, those workers are paid less on average and promoted less often than others with the same education and ability. As a result of the inefficient and discriminatory wage and promotion policies, disadvantaged workers experience lower returns to investments in human capital than other workers.

With multiple, prestigious co-authors he has written in favor of prediction markets.

He was the doctoral advisor of Susan Athey, and in Alex’s post you can read about his auction advising and the companies he has started.

His wife, Eva Meyersson Milgrom, is herself a renowned social scientist and sociologist, and he met her in 1996 while seated next to her at a Nobel Prize dinner in Stockholm. Here is one of his papers with her (and Ravi Singh), on whether firms should share control with outsiders. Here is the story of their courtship.

The social function of Harvard and other elite universities

Here is a new study by Valerie Michelman, Joseph Price, and Seth D. Zimmerman:

This paper studies social success at elite universities: who achieves it, how much it matters for students’ careers, and whether policies that increase interaction between rich and poor students can integrate the social groups that define it. Our setting is Harvard University in the 1920s and 1930s, where students compete for membership in exclusive social organizations known as final clubs. We combine within-family and room-randomization research designs with new archival and Census records documenting students’ college lives and career outcomes. We find that students from prestigious private high schools perform better socially but worse academically than others. This is important because academic success does not predict earnings, but social success does: members of selective final clubs earn 32% more than other students, and are more likely to work in finance and to join country clubs as adults, both characteristic of the era’s elite. The social success premium persists after conditioning on high school, legacy status, and even family. Leveraging a scaled residential integration policy, we show that random assignment to high-status peers raises rates of final club membership, but that overall effects are driven entirely by large gains for private school students. Residential assignment matters for long-run outcomes: more than 25 years later, a 50-percentile shift in residential peer group status raises the rate at which private school students work in finance by 37.1% and their membership in adult social clubs by 23.0%. We conclude that the social success premium in the elite labor market is large, and that its distribution depends on social interactions, but that the inequitable distribution of access to high-status social groups resists even vigorous attempts to promote cross-group cohesion.

You can think of this as another attempt to explain the relatively high returns to education, without postulating that students learn so much, and without emphasizing signaling so much. Going to Harvard is in fact winning access to a very valuable set of networks (which in turn is signaling as well, to be clear).

For the pointer I thank Tyler Ransom.

Friday assorted links

1. “San Diego is now home to the largest mass surveillance operation across the country.” And 23andMe to start layoffs.

2. Joseph Ferraro does a podcast with me, his core theme is how to get one percent better every day. Much of this one is on my interviewing philosophy. With the passing of Terry Jones, it is worth noting that the single biggest influence on my interviewing philosophy probably is Monty Python. Whenever they would start a skit with an interview set up, and two people in chairs, I felt something especially good was coming up (try “Miss Anne Elk”). What a delicious sensation! Thus it seemed to me that an interview should grab the attention of the listener/viewer right away. My friend Noam understands quite well how rooted a good podcast (including CWT) is in entertainment, no matter what the ostensible topic may be.

3. Coronavirus data?

5. Bryan Caplan on austerity for education, a response to me. I say the actual equilibrium of price controls for higher education is that public spending does not make up the gap, and you end up with something like the German system. I don’t favor this, to be clear, but there is much less higher ed signaling in Germany than the United States, even though the German system is very close to nominally free for students.

Non-cognitive skills and earnings in Canada

This newly published paper (click on the first link here) by McLean, Bouaissa, Rainville, and Auger confirms some more general results, usually taken from American data:

Our results indicate that conscientiousness is positively associated with wages, while agreeableness, extraversion, and neuroticism are associated with negative returns, with higher magnitudes on agreeableness and conscientiousness for females. Cognitive ability has the highest estimated wage return so, while significant, non-cognitive skills do not seem to be the most important wage determinant.

The main difference seems to be that in Canada extraversion is correlated with lower earnings, but in the United States in general it is not. And note that a one standard deviation increase in agreeableness for women is associated with a 7.4-8.7% income penalty, but no corresponding income penalty for men. Finally, (p.112) that the rate of return on education is over seven percent, and after adjusting for cognitive level this falls by only 30 percent, relevant for the signaling model of education of course.

Is free college a good idea?

C’mon people, this one should be a no-brainer, can’t you at least call upon your craven loyalty to the higher education lobby to reject the free tuition proposals from Warren and Sanders?:

Just three German universities placed in the top 100 world institutions in rankings compiled by Quacquarelli Symonds, a British education consultancy…

In Germany, public funds covered $14,092 per student in 2015, the latest year for which the OECD has compiled numbers. In the United States, public funds covered $10,563 per student. But once private money was taken into account, U.S. university spending was far higher: $30,003 per student, compared with $17,036 in Germany…

“The best German universities look a lot like the University of Colorado. It’s not going to be like the top privates. It’s not even going to be like the top publics,” said Alex Usher, a Canadian education consultant who has studied how countries fund their university systems. “They’re perfectly good schools. They churn out good graduates. They’re not as focused on creating an elite. And in many ways that’s what the top systems in the United States are trying to do.”

The German system is entirely defensible if you believe that higher education is largely a matter of wasteful signaling; that is not my view, but believe it or not I know a few people who hold it.

The simple reality is that when it comes to higher education policy, President Trump is much better than the Democratic Party thought leaders.

#thegreatforgetting

What I’ve been reading

1. Robert W. Poole, Jr. Rethinking America’s Highways: A 21st Vision for Better Infrastructure. Highways can and will get much better, largely through greater private sector involvement. He is probably right, and there is much substance in this book.

2. Aysha Akhtar, Our Symphony with Animals: On Health, Empathy, and Our Shared Destinies. An unusual mix of memoir, animal compassion, and childhood horrors, I found this very moving.

3. Ethan Mordden, On Streisand: An Opinionated Guide. Should there not be a fanboy book like this about every person of some renown? Insightful and witty throughout, for instance: “…we comprehend Streisand from what she does — yet a few personal bits have jumped out at us through her wall of privacy. One is the “Streisand Effect”…which we can restate as “When famous people complain about something, they tend to make it famous, too.”

4. Jason Brennan and Phillip Magness, Cracks in the Ivory Tower: The Moral Mess of Higher Education. Hard-hitting and courageous, and I can attest that much of it is absolutely on the mark. Still, I did wish for a bit more of a comparative perspective. Are universities more hypocritical than other institutions? Might the non-signaling, learning rate of return on higher education still be positive and indeed considerable? I am not nearly as negative as the authors are, while nonetheless feeling much of their disillusion on the micro level. Furthermore, American higher education does pass a massive market test at the global level — foreign students really do wish to come and study here. What are we to make of that? Which virtues of the current system are we all failing to understand properly?

5. Kirk Goldsberry, Sprawlball: A Visual Tour of the New Era of the NBA. A highly analytical but also entertaining look at the rise of the three point shot, the history of Steph Curry, how LeBron James turned into such a good player, and much more, with wonderful visuals and graphics.

6. Paul Rabinow, Making PCR: A Story of Biotechnology. PCR is the polymerase chain reaction, and this is a genuinely good anthropological study of how scientific progress comes about, noting there is plenty of lunacy in this story, including love, LSD, and much more. There should be more books like this, this one dates from the 1990s but I am still hoping more people copy it. Via Ray Lopez.

Charles King, Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century, covers Boas, Mead, Benedict, and others. Not enough of the material was new to me, though I expect for many readers this is quite a useful book.

I enjoyed Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution.

Daniel Markovits, The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite. Remember how I used to say “The only thing worse than the Very Serious People are the Not Very Serious People?” Well, you should have listened. I have the same fear with the current critiques of meritocracy. That said, this is the book that does the most to pile on, against meritocracy, noting that much less space is devoted to possible solutions. There are arguments in their own right for wage subsidies and more low-income college admissions, but will those changes reverse the fundamental underlying dynamic of knowing just about everybody’s marginal product?

John Quiggin, Economics in Two Lessons: Why Markets Work So Well, and Why They Can Fail So Badly. The third lesson, however, is government failure, and you won’t find much about that here. Still, I found this to be a well-done book rather than a polemic. Here is the introduction on-line.

Tuesday assorted links

1. “I still want this, all of it. I want the tears; I want the pain.” (NYT) Recommended.

2. “Cultural revolutions reduce complexity in the songs of humpback whales.”

3. ““If I could have sold off a suicide attempt,” she said in a 2008 interview, “I would have had more time for reading Spinoza.” Duh.” Link here, that is the excellent Helen DeWitt, interesting throughout.

5. The new “woke”: “Is Lord of the Rings prejudiced against Orcs?”

How does your personality correlate with your paycheck?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Gensowski revisits a data set from all schools in California, grades 1-8, in 1921-1922, based on the students who scored in the top 0.5 percent of the IQ distribution. At the time that meant scores of 140 or higher. The data then cover how well these students, 856 men and 672 women, did through 1991. The students were rated on their personality traits and behaviors, along lines similar to the “Big Five” personality traits: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

One striking result is how much the trait of conscientiousness matters. Men who measure as one standard deviation higher on conscientiousness earn on average an extra $567,000 over their lifetimes, or 16.7 percent of average lifetime earnings.

Measuring as extroverted, again by one standard deviation higher than average, is worth almost as much, $490,100. These returns tend to rise the most for the most highly educated of the men.

For women, the magnitude of these effects is smaller…

It may surprise you to learn that more “agreeable” men earn significantly less. Being one standard deviation higher on agreeableness reduces lifetime earnings by about 8 percent, or $267,600.

There is much more at the link, and no I do not confuse causality with correlation. See also my remarks on how this data set produces some results at variance with the signaling theory of education. Here is the original study.

My Conversation with Bryan Caplan

Bryan was in top form, I can’t recall hearing him being more interesting or persuasive. Here is the audio and text. We talked about whether any single paper is good enough, the autodidact’s curse, the philosopher who most influenced Bryan, the case against education, the Straussian reading of Bryan, effective altruism, Socrates, Larry David, where to live in 527 A.D., the charm of Richard Wagner, and much more. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: You love Tolstoy, right?

CAPLAN: Yeah. You love Tolstoy because here’s a guy who not only has this encyclopedic knowledge of human beings — you say he knows human nature. Tolstoy knows human natures. He realizes that there are hundreds of kinds of people, and like an entomologist, he has the patience to study each kind on its own terms.

Tolstoy, you read it: “There are 17 kinds of little old ladies. This was the 13th kind. This was the kind that’s very interested in what you’re eating but doesn’t wish to hear about your romance, which will be contrasted with the seventh kind which has exactly the opposite preferences.” That’s what’s to me so great about Tolstoy.

Here is one of my questions:

What’s the fundamental feature in Bryan Caplan–think that has made you, unlike most other nerds, so much more interested in Stalin than science fiction?

Here is another exchange:

COWEN: You think, in our society in general, this action bias infests everything? Or is there some reason why it’s drawn like a magnet to education?

CAPLAN: Action bias primarily drives government. For individuals, I think even there there’s some action bias. But nevertheless, for the individual, there is the cost of just going and trying something that’s not very likely to succeed, and the connection with the failure and disappointment, and a lot of things don’t work out.

There’s a lot of people who would like to start their own business, but they don’t try because they have some sense that it’s really hard.

What I see in government is, there isn’t the same kind of filter, which is a big part of my work in general in politics. You don’t have the same kind of personal disincentives against doing things that sound good but actually don’t work out very well in practice.

Probably even bigger than action bias is actually what psychologists call social desirability bias: just doing things that sound good whether or not they actually work very well and not really asking hard questions about whether things that sound good will work out very well in practice.

I also present what I think are the three strongest arguments against Bryan’s “education is mostly signaling” argument — decide for yourself how good his answers are.

And:

COWEN: …Parenting and schooling in your take don’t matter so much. Something is changing these [norms] that is mostly not parenting and not schooling. And they are changing quite a bit, right?

CAPLAN: Yes.

COWEN: Is it like all technology? Is the secret reading of Bryan Caplan that you’re a technological determinist?

CAPLAN: I don’t think so. In general, not a determinist of any kind.

COWEN: I was teasing about that.

And last but not least:

CAPLAN: …When someone gets angry at Robin, this is what actually outrages me. I just want to say, “Look, to get angry at Robin is like getting angry at baby Jesus.” He’s just a symbol and embodiment of innocence and decency. For someone to get angry at someone who just wants to learn . . .

COWEN: And when they get mad at me?

CAPLAN: Eh, I understand that.

Hail Bryan Caplan! Again here is the link, and of course you should buy his book The Case Against Education.