Results for “food” 1948 found

Rachel Lauden is wise about food

The still-underrated Todd Kliman interviews her:

I’ve been given special powers, and I appoint you czar (funny, isn’t it, how we have so many appointed czars in this unaristocratic country) of food in the US. What is your first order of business? What sorts of laws do you push for? What public statements do you make? What is your 5-year plan? Your 10?

Me? A czar? My first order of business would be to go to the bathroom and throw up in sheer terror. I’m not a fan of appointed czars or of five-year plans. I am a fan of incremental changes. Look what’s happened in the 15 years since I wrote the article. Walmart’s become a major player, so has Monsanto, celebrity chefs, sustainability, and locavore have become household words, fats and sweeteners have been vilified and un-vilified, and now Taco Bell is removing artificial flavoring and coloring, corporations are scrambling to make their products appealing to those who want healthful and organic foods, and McDonald’s is in trouble. No one could have predicted or managed these changes. And many have happened through the power of the word. So I’d turn down the offer. The pen is mightier than the czar!

3-D printed food

Marijn Roovers’ epicurean delights have graced the tables of some of the Netherlands’ finest restaurants. But the food designer’s Chocolate Globe is his most intricate — and technologically advanced — creation. A chocolate shell just 0.8 millimetres thick is embossed in gold with the chocolate’s continent of origin, and it holds delicacies that symbolize the region.

Roovers and chef Wouter van Laarhoven printed it — layer-by-layer of chocolate — on a 3D printer. Roovers is at the forefront of a small group of gourmets and technophiles who want to revolutionize how food is prepared. On 21 April, they will gather in the Netherlands for the first conference dedicated to the 3D printing of food.

But do note this:

3D food printers tend to be slow: Roovers’ chocolate globes, for example, currently take about an hour to print. To prepare one per guest in a restaurant with 40 patrons would take almost 2 days of continuous printing. “It’s not very realistic,” he says. “At the moment it’s a way to show craftsmanship.”

Then there is the matter of texture. Most 3D printers work with either pastes or powders, so the resulting food tends to be mushy, says Julian Sing, founder of 3DChef, a firm near Tilburg, Netherlands, that specializes in 3D printing of sugar. “The food needs to have the right texture,” he says. “It needs to look like food and not like slop.”

There is more here, via Michelle Dawson.

How to find good Iranian food

I hardly ever blog Iran, most of all because I’ve never been there, but perhaps the time has come to serve up the meager amount I do know about the place. Let’s start with food, here are a few propositions about Iranian food, at least as it is found in the West:

1. Choose a restaurant which has a diversity of rices, such as zereskh polo (rice with barberries). Or sour cherry rice. The rice you order is a more important decision than the kabob you order. Personally, I like to commit the heresy of loading up a tart rice with a gooey yogurt concoction, such as Mast-o-Mosir, spellings on that one will vary greatly.

2. Choose a restaurant with koreshes, namely stews. The kabobs get boring, Afghan kabobs in this country are usually better anyway, so over time you should end up getting the stews in a Persian restaurant.

3. It is very hard to find Iranian restaurants in the United States which break from the usual medley of offerings. The good news is that there are very few bad Iranian restaurants around.

4. The best Iranian restaurants in this country are probably those in and near Westwood, Los Angeles, not far from UCLA.

5. If you get Iranian bread, it looks boring. But load it up with the spicy green sauce, butter, and yes sliced onion. Then it’s really yummy. Don’t be put off if your bread shows up cold and embedded in plastic wrap, just add the condiments and it will be yummy.

6. I always like the soups, but in this country opt for “minty” over “barley.”

7. Iranian food in Germany and London is also quite good, I don’t think I have had it elsewhere.

8. Buying fesenjan sauce out of a can and cooking with it is much tastier than you might think. This is super-easy and inexpensive. Fesenjan sauce, in case you don’t know, is a kind of walnut and pomegranate mix, for you vegans it works OK with tofu.

9. At the end of writing this post, my own googling led me to a 2009 post I had written on the same topic but had forgotten about completely, it is here if you wish to compare. If nothing else, it shows my views on Iranian food are pretty consistent over time, as is the food itself.

Los Angeles food bleg

Where to eat? Probably you can forget the rest, unless you ought to rationally think I do not already know of it.

All you can eat books vs. all you can eat food

…a new complaint is about Kindle Unlimited, a new Amazon subscription service that offers access to 700,000 books — both self-published and traditionally published — for $9.99 a month.

It may bring in readers, but the writers say they earn less.

Here is some analysis:

“Your rabid romance reader who was buying $100 worth of books a week and funneling $5,200 into Amazon per year is now generating less than $120 a year,” she said. “The revenue is just lost. That doesn’t work well for Amazon or the writers.”

Amazon, though, may be willing to forgo some income in the short term to create a service that draws readers in and encourages them to buy other items. The books, in that sense, are loss leaders, although the writers take the loss, not Amazon.

And when it comes to food?:

New research shows that paying that much for a buffet might actually make the food taste better. Three researchers did an all you can eat (AYCE) buffet field experiment to test whether the cost of an AYCE buffet affected how much diners enjoyed it. They conducted their research at an Italian AYCE buffet in New York, and over the course of two weeks 139 participants were either offered a flier for $8 buffet or a $4 buffet (both had the same food). Those who paid $8 rated the pizza 11 percent tastier than those who paid $4. Moreover, the latter group suffered from greater diminishing returns—each additional slice of pizza tasted worse than that of the $8 group.

“People set their expectation of taste partially based on the price—and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If I didn’t pay much it can’t be that good. Moreover, each slice is worse than the last. People really ended up regretting choosing the buffet when it was cheap,” said David Just, professor at Cornell’s Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, and one of the study’s authors.

In the old days one heard speculation about bundling a great number of newspapers and blogs into a single-price access model, but in retrospect this probably never had much financial potential, for reasons which by now should be clear. What would an “all-you-can-eat buffet for economists” mean? And who if anyone would benefit from it?

Food is cheaper in large cities

Eliminating heterogeneity bias causes 97 percent of the variance in the price level of food products across cities to disappear relative to a conventional index. Eliminating both biases reverses the common finding that prices tend to be higher in larger cities. Instead, we find that price level for food products falls with city size.

That is part of an abstract and new paper from Jessie Handbury and David E. Weinstein, via Kevin Lewis. They have two additional interesting papers on the cost of living here.

Facts about food

Stanford’s Dan Jurafsky has written a book doing just that. In The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu, Jurafsky describes how he and some colleagues analyzed a database of 6,500 restaurant menus describing 650,000 dishes from across the U.S. Among their findings: fancy restaurants, not surprisingly, use fancier—and longer—words than cheaper restaurants do (think accompaniments and decaffeinated coffee, not sides and decaf). Jurafsky writes that “every increase of one letter in the average length of words describing a dish is associated with an increase of 69 cents in the price of that dish.” Compared with inexpensive restaurants, the expensive ones are “three times less likely to talk about the diner’s choice” (your way, etc.) and “seven times more likely to talk about the chef’s choice.”

Lower-priced restaurants, meanwhile, rely on “linguistic fillers”: subjective words like delicious, flaky, and fluffy. These are the empty calories of menus, less indicative of flavor than of low prices. Cheaper establishments also use terms like ripe and fresh, which Jurafsky calls “status anxiety” words. Thomas Keller’s Per Se, after all, would never use fresh—that much is taken for granted—but Subway would. Per Se does, however, engage in the trendy habit of adding provenance to descriptions of ingredients (Island Creek oysters, Frog Hollow’s peaches). According to Jurafsky, very expensive restaurants “mention the origins of the food more than 15 times as often as inexpensive restaurants.”

There is more here, you can pre-order the book here. My previous posts about this work are here.

Animals suffer under food nationalism

The more than 6,000 animals in Russia’s largest zoo have been caught up in the worst fight between Russia and the West since the Cold War. A wide-ranging ban on Western food announced this week by the Kremlin has forced a sudden diet change for creatures that eat newly forbidden fruit.

The sanctions against meat, fish, fruits and vegetables from the United States, the European Union and other Western countries were intended to strike a counterblow to nations that have hit Russia over its role in Ukraine’s roiling insurgency. But the measures will also have an impact on stomachs at the zoo.

The sea lions crack open Norwegian shellfish. The cranes peck at Latvian herring. The orangutans snack on Dutch bell peppers. Now the venerable Moscow Zoo needs to find politically acceptable substitutes to satisfy finicky animal palates.

“They don’t like Russian food,” zoo spokeswoman Anna Kachurovskaya said. “They’re extremely attached to what they like, so it’s a hard question for us.

The penguins still live in a Cobdenite world:

The penguins eat fish from Argentina — whose food sales to Russia have not been blocked and are politically in the clear.

But the Ramsey rules are relevant for some of the primates:

Orangutans, gorillas and monkeys are particularly finicky eaters at the zoo, but Kachurovskaya said they would eventually adapt.

“In the wild, they eat what they have, not what they want,” she said.

The story is here.

Ian Bremmer on Ukraine, and an observation on Putin’s food import ban

Putin’s Plan A: Long game, squeeze Ukraine, force deep federation, formalize Russian influence & primacy in SE

Plan B: Invade

The link to that tweet is here. There is more from Ian here.

I find it worrying that Putin is suspending food imports from parts of the West. (Note that the text of the ban may be deliberately ambiguous.) Commentators are criticizing the economics of such a move, but I think of this more in terms of Bayesian inference. Long-term elasticities are greater than short. Under the more pessimistic reading of the action, Putin is signaling to the Russian economy that it needs to get used to some fairly serious conditions of siege, and food is of course the most important of all commodities. Why initiate such a move now if you are expecting decades of peace and harmony? Or is Putin instead trying to signal to the outside world that he is signaling “siege” to his own economy? Then it may all just be part of a larger bluff. In any case, Eastern Europeans do not take food supply for granted.

China fact of the day, or why Chinese food will decline in quality (and rise in safety)

In the United States, at least 70 percent of all the food we eat each year passes through a cold chain. By contrast, in China, less than a quarter of the country’s meat supply is slaughtered, transported, stored or sold under refrigeration. The equivalent number for fruit and vegetables is just 5 percent.

The article has other points of interest, an excellent piece by Nicola Twilley.

The new French food regulations (“fait maison”) are poorly designed

Elaine Sciolino is pretty critical. She writes:

A new consumer protection law meant to inform diners whether their meals are freshly prepared in the kitchen or fabricated somewhere off-site is comprehensive, precise, well intentioned — and, to hear the complaints about it, half-baked.

Public decree No. 2014-797, drafted and passed by the French Parliament and approved by the prime minister, went into effect last week. It allows restaurateurs to use the logo if they have resisted the increasing temptation to buy ready-made dishes from industrial producers, pop them in the microwave and pass them off as culinary artistry.

It doesn’t seem to be working to encourage quality:

French fries, for instance, can bear the “fait maison” symbol if they are precut somewhere else, but not if they are frozen. Participating chefs are allowed to buy a ready-made pâte feuilletée, a difficult-to-make, multilayered puff pastry, but pâte brise, a rich pastry dough used to make flaky tart shells, has to be made on-site. Cured sausages and smoked hams are acceptable, while ready-made terrines and pâtés are not.

…Périco Légasse, a food critic for the weekly magazine Marianne, wrote: “ ‘Homemade’ doesn’t mean freshly made. A dish totally prepared with frozen products, even if they come from a Romanian slaughterhouse, can enjoy this happy distinction as it was cooked on-site.”

Mark Bittman piles on. I would stress there is no substitute for consumers who demand the right kind of food and who otherwise won’t buy it.

How to find good food in Chengdu

1. Many people in Chengdu are experts on the local food scene. Recruit one of them, but don’t be shocked if they insist on paying for your meal every time.

2. Go downtown to the Crowne Plaza hotel, walk out on the main road to your left, and within two minutes you will see on your left a “TangSong food street” — a covered food court about twenty-five small Sichuan places. There is a sushi place too but I saw the customers dipping their sushi rolls in hot red chili oil. It is heartwarming to walk into such a culinary universe.

2b. Within this court my favorite place is labeled “1862 History,” you might spot the small print, in any case the place looks spare and is somewhat larger than the very small venues.

3. MaPo tofu is much finer here, and the black peppers and quality vinegars are to be appreciated.

4. Sichuan chili chicken and Dan Dan noodles are two of my favorite Sichuan dishes back home. Here they have been good, but actually slightly disappointing relative to expectations. Don’t obsess over those during your quest.

4b. There are two philosophies of international trade. In one philosophy, the best dishes are the best dishes and so you should order them at home and also order them abroad in their countries of origin. In the second philosophy, it is the most exportable dishes which get exported but they are not in general the best dishes period. When abroad you therefore should try out the dishes you cannot find at home. For Chengdu at least, this second philosophy is the correct one as Jacob Viner had hinted way back in the mid-1930s.

5. Often the most interesting dishes are the accompanying vegetables. For instance at a hot pot restaurant I had excellent elongated yam cubes coated in a (slightly sweet) blueberry sauce and stacked ever so perfectly. It was the ideal offset to the hotness and tingle of the core dishes. At another restaurant I most enjoyed some simple greens dipped in a sesame soy sauce. Or try potato or lotus root in hot pot.

6. Unless you go to great lengths to avoid this fate, you will end up eating strange parts of the animal. You won’t like all of them, but you won’t dislike all of them either.

6b. If you utter “Ma La” with conviction, they will think you are remarkably sophisticated or perhaps even fluent in Chinese. The populace here seems unaware that some version of real Sichuan food is now reasonably popular in the United States.

7. Many menus have photos, but they show lots of red and are not useful for identifying exactly what you will be eating. See #6.

8. There are two areas — Jin Li and Wenshu Fang — where old buildings and streets are recreated and you can stroll in a kind of outdoor shopping mall. Everyone goes to these locales and they are fun. These neighborhoods are good for finding lots of takeaway Sichuan snacks, including desserts, in a single area, and served in sanitary conditions. That said, I don’t think these are the very best Sichuan goodies to be had in town, as they are designed explicitly for tourists, albeit food-loving Chinese tourists.

9. “Chengdu food” and “Sichuan food” are not the same thing. Sichuan province has more people than France, and Chengdu is simply one large city, and so your favorite Sichuan dish may not be a staple here. The town also has a fair amount of Tibetan food, though I haven’t tried any.

10. If you leave Chengdu confused as to exactly where and what you ate, you probably had a very good food trip.

*The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu*

That is the new and excellent book by Dan Jurafsky, due out this September, and I found it interesting throughout. Here is just one bit:

In fact, the more Yelp reviewers mention dessert, the more they like the restaurant. Reviewers who don’t mention a dessert give the restaurants an average review score of 3.6 (out of 5). But reviewers who mention a dessert in their review give a higher average review score, 3.9 out of 5. And when people do talk about dessert, the more times they mention dessert in the review, the higher the rating they give to the restaurant.

This positivity of reviews, filled with metaphors of sex and dessert, turns out to be astonishingly strong.

That is another reason not to trust customer-generated restaurant reviews.

And how exactly do Americans conceive of dessert?

Americans usually describe desserts as soft or dripping wet…US commercials emphasize tender, gooey, rich, creamy food, and associate softness and dripping sweetness with sensual hedonism and pleasure.

This association between soft, sticky things and pleasure isn’t a necessary connection. For example, Strauss found that Korean food commercials emphasize hard, textually stimulating food, using words like wulthung pwulthung hata (solid and bumpy), coalis hata (stinging, stimulating), thok ssota (stinging), and elelhata (spicy to the extent one’s nerves are numbed).

How can you resist a book with sentences such as these?

The pasta and the almond pastry traditions merged in Sicily, resulting in foods with characteristics of both.

Here is a previous MR post on Jurafsky, including a link to his blog, and concerning “Claims about potato chips.”

Should you scorn seafood in the American Midwest?

Bruce Arthur, a loyal MR reader, writes to me:

I grew up in a Polish immigrant neighborhood in Chicago, where I was raised on a diet high in seafood. My mother was raised close to the Baltic Sea and we weekly went to the local grocery store and bought a lot of salmon, halibut, sea bass, and scallops. I thought it was absolutely delicious. Sometimes we went to local ethnic grocery stores (generally Italian, the Italians had lived in the neighborhood before the Poles came and still ran a lot of businesses) and bought fish that was whole rather than filleted.

When I went off to college, I encountered people from the East Coast for the first time in my life, and I was shocked to learn that they did not believe that good seafood could possibly exist far away from an ocean coast. They would say things like “I would never eat fish in the Midwest, I wouldn’t trust it!’, which, as an 18 year old who was very much alive after eating a lot of fish in the Midwest, I found absurd.

After all, I thought, isn’t most seafood globally sourced these days? Few of our common food fishes are actually native to the Atlantic Coast, and if you’re flying fish in from the Pacific Northwest, South America, or Oceania, it seems to me that it should be least fresh on the East Coast, which is the part of America furthest away from where these fish are actually caught.

Of course, there could be other factors. Perhaps fish is freshest not closest to the ocean, but in denser areas – if everything is closer together, the places where fish is bought and eaten are presumably closer to the site of its first arrival in the area. Perhaps there’s a cultural factor: fish wasn’t always globally sourced, so perhaps coastal areas have more fish tradition that results in a higher quality of food. But surely the historic high rate of movement within (and into) America weakens that effect.

Anyway, I’m wondering if you have any insight into this. Am I right to scoff at regional seafood snobs, or do they have a point?

The more important reality is that hardly any regions in the United States have good indigenous seafood these days and thus no relative snobbery is justified. Maine lobster or catfish in parts of the south might be exceptions, and in neither case does the Alchian and Allen theorem hold (i.e., the highest quality goods remain those closest to the source).

In general regional demand effects are strong, as I argue in An Economist Gets Lunch. People outside of southern Ohio don’t understand good Cincinnati chili and so they don’t get it. The ingredients can in fact be transferred to North Carolina but they aren’t, least of all with the proper applications. A lot of good Sichuan dishes can be reproduced reasonably well in the United States, but you don’t get them until the properly demanding clientele is in place (by the way Gourmet Kingdom in Carrboro, NC is excellent). Who amongst us is a properly demanding judge of asam laksa? And so on. One interesting feature of these equilibria is that regional mobility does not seem to undo them. If you move to southern Ohio, you can rather rapidly become a standard bearer of good taste in chili, but you slack off once you are back in northern Virginia.

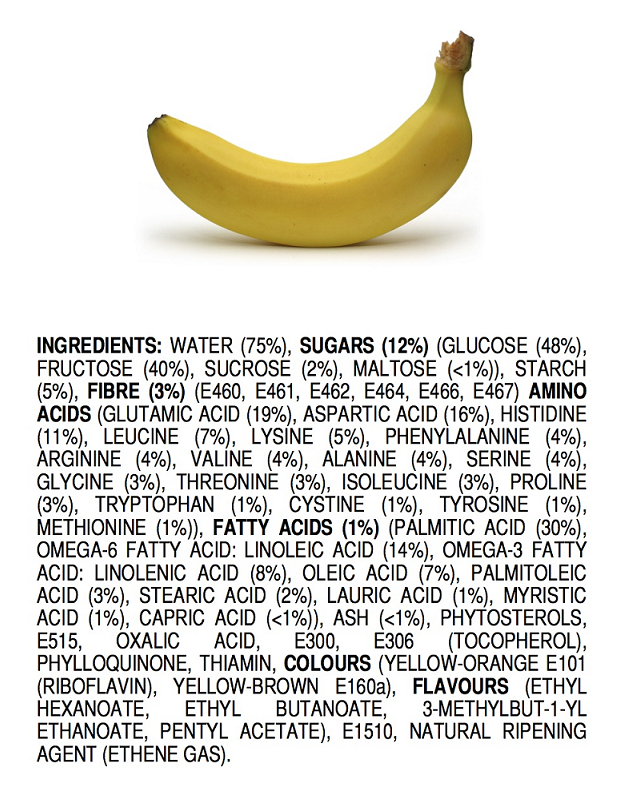

The Chemicals in Our Food

More here.