Results for “more police” 437 found

The Haitian police

Haiti has one of the world’s weakest police forces. There are 63 police officers per 100,000 people, less than a quarter of the regional average of 283 per 100,000 and only a third of the average for sub-Saharan African countries. Moreover, a significant number of members of the Haitian National Police (HNP) are alleged to be involved in criminal and violent activities, including direct involvement in the past year’s wave of kidnappings, according to human rights organizations and police officials themselves.

That's pre-earthquake. Here are 118 pp. on other Haitian social and political indicators.

Markets in Everything: Police

Serbs seeking a bit of extra

protection or perhaps a helicopter for the weekend can now turn

to the police, which from this month will be renting out its

personnel, transport and even animals for private use.

More here. Of course, there is a history of private firms hiring police in Washington, DC.

Thanks to Carl Close for the pointer.

Terror Alerts, Police and Crime

If you look at a simple correlation between crime per capita and police per capita you get this:

Police cause crime! Some of the Foucault-inspired may buy into that conclusion but it’s really no surprise that places with a lot of crime have a lot of police. Estimating the true effect of police and crime from observational data is difficult because police and crime are determined jointly.

Ideally, to estimate the true causal effect of police on crime, we would run an experiment, randomly picking weeks in which we increased police presence and observing the effect on crime. Experiments like this, however, are expensive and some might say unethical. If we look carefully, however, we might find natural experiments – times when police presence increased for reasons that are random with respect to crime.

Jon Klick and I look at just such a natural experiment in a paper published in the most recent JLE, Using Terror Alert Levels to Estimate the Effect of Police on Crime (subs. required, free version). When the terror alert system kicks up a notch the police in Washington, DC put more police on the streets. We find that crime in DC drops significiantly during these high-alert periods, especially in the National Mall area where most of the prime terror-targets are located. Street crimes like auto theft and theft from automobiles show especially large decreases when more police hit the street. We find no evidence that tourism or other demand side factors account for the decline in crime.

Why did we become the world’s policeman?

The ever-effervescent Jane Galt poses this obvious yet profound question:

…why did we agree to be the world/s policeman? The rest of the developed world essentially opted out of military development in favour of building their welfare states–why didn’t we? After all, we were perhaps the country least threatened by the Soviet Union.

I don’t think the standard imperialist answer holds. Sure, we have done some unsavoury things in order to promote our country’s economic interest, but shockingly fewer such things than any other country I can think of. The US has generally pursued its imperialistic expeditions in ways that are fairly altruistic — either ideological, or in pursuit of broadly stabilising actions such as trying to keep the Middle East fairly peaceful so that oil continues to flow, an action that benefits anpetrological countries far more than the US. Why did we take on the superpower project, and why didn’t we exploit our role as much as we could have?

My take: Even if the rest of the world hates us (debatable, in my view, but let’s say), being the world’s policeman is high status in American eyes. On top of that, most American leaders, and most ordinary Americans, think it is the proverbial “right thing to do,” and think that we do a relatively good job of it. Plus we get some economic benefits, such being able to bribe or bully people to open up their markets or buy our Treasury securities. When relative status, perceptions of right and wrong, and (some) economic self-interests all push in the same direction, the mix is potent. For the clincher, people have strong psychological tendencies to want to feel “in control.” Many people fear flying so much, precisely because they feel they have no control over the risk. Forget about the world, some people even try to control their teenagers, how is that for a laugh?

Or you might pose another, simpler question. How many Presidents run for a second term? Almost all of them. It’s not good for their income, and arguably it is not even good for their happiness. Most look like hell when they leave office. But they like being in control.

The bottom line? Whether you like it or not, America is not going to give up this policeman role anytime soon.

China fact of the day, once more

In Beijing, dogs are not allowed outside in the daytime; those caught outdoors are confiscated and killed. They are not allowed in parks, on grass or on elevators – even when elderly owners live on the 14th floor. They may not grow taller than knee-high, on pain of death. And licenses are expensive.

The predictable result: many dogs never go outside. Thousands are confiscated each year for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or growing a little too big. In the back alleys, where the police can’t drive, families flout the law and play with their pets outside during the day. In fancier parts of town or near any major street, nobody dares.

Now The New York Times goes out on a limb:

Many dog owners are seething, even as their pets suffer…Matters like this, as much as censorship of the press and the jailing of dissidents, may determine the fate of the Communist Party.

Here is an article on new dog regulations in China. The yearly registration fee used to start at $600 for the first year, now it is $121, read here. Here is a Chinese “man bites dog” story (seriously). Here is an article on dog deregulation in southern China.

The Effect of Police on Crime

Estimating the effect of police on crime is more difficult than it sounds because places with a lot of crime tend to have a lot of police and vice-versa. As a result, naive analyses tend to find that police cause crime! Jon Klick and I, following the amazing Steve Levitt, have what we think is a pretty clever solution. We look at what happens to crime in Washington DC when the terror alert level rises from elevated to high. During a high-alert period the police put on extra shifts, monitor closed circuit cameras on the National Mall and in general step-up policing. We find that crime falls a lot during these high-alert periods. Our new paper is, Using Terror Alert Levels To Estimate the Effect of Police on Crime. Comments welcome.

Here is the abstract:

We argue that changes in the terror alert level set by the Department of Homeland Security provide a shock to police presence in the Mall area of Washington, D.C. Using daily crime data during the period the terror alert system has been in place, we show that crime drops significantly, both statistically and economically, in the Mall area relative to the other areas of Washington DC. This provides strong evidence of the causal effect of police on crime and suggests a research strategy that can be used in other cities.

Flying coast to coast

An email from an anonymous MR reader, I will apply no further indentation:

“I’m flying non-stop today from SFO to IAD, and I thought you might be interested in reading this, because I haven’t seen anything similar since the start of covid maybe.

– Highway to SFO had more police presence than usual.

– I took a morning flight out of the airport, and driving though the airport roads to get to the right terminal felt quite eerie. Perhaps only saw one or two cars the whole time until we got to the terminal, and even then, I didn’t see more than three cars in front of each terminal dropping off passengers.

– I saw maybe 20 people (including employees) total in the terminal pre-TSA check. Only two travelers were not wearing masks, and none wore gloves. Every employee was wearing a mask, and almost all, if not all, were wearing gloves. None of them

– 6 feet apart reminder stickers are everywhere, including on seats.

– TSA forced distancing during security check, though not if you were traveling with other people.

– All TSA employees were wearing masks and nitrile gloves.

– Electric walkways were shut off to “conserve energy”

– I saw about 150 people (travelers, airport employees, airline employees and shop employees) on my way to the gate from security check. I’d say 5-7% weren’t wearing masks. Of the three pilots I saw, none were wearing masks or gloves.

– A lot more people than usual had paper tickets, which leads me to believe that they were all leaving SF for at least a few weeks, if not a few months (I checked my bag and was given a paper ticket even though I had the QR code on my phone). This is interesting economically given how many people are expected to file for unemployment benefits in SF over the next few weeks, and I know a lot of people who are breaking their leases and going to live with parents or someplace cheap like Nevada or Oregon.

– I boarded a 777-200 via United. I normally fly Southwest, but I think they aren’t doing coast-to-coast flights on weekends for the foreseeable future. I think almost everyone on the plane had their own row. Anyone who was sitting in the aisle was asked to move at least one seat over to allow some distancing while people walk back and forth on the plane.

– All of the flight attendants were wearing masks.

– The usual safety demonstration was conducted, but the flight attendants held up and pointed to the section in the safety card while the pilot was speaking, instead of using the life vest like normal. I suppose it was because the airline didn’t want them to take off their masks to demonstrate blowing into the tube of the life jacket.

– Prepackaged drinks and snacks only. They gave everyone two small water bottles, an additional choice of drink (only water and various juices), and three snacks. (Like I said, I usually fly Southwest and can’t remember the last time I flew United. This particular detail may or may not be relevant ¯\_(ツ)_/¯)

– Everyone had the option of a blanket. They normally don’t wash these very often, so I wonder if covid forced them to wash it after every use.

– A lot more

– A few landing strips were blocked, not sure why.

– A lot more cargo ships in the bay (not docked) than what I’m used to seeing, though I could be wrong.”

Reader, when do you expect to take your next plane flight?

How Much Time Do Criminals Really Serve?

Many people were surprised at Paul Manafort’s relatively light sentencing for bank fraud, filing fake tax returns, and failure to report foreign assets and compared his sentence of 47 months to other cases of seemingly lesser crimes given longer prison terms. A viral tweet thread from public defender Scott Hechinger began:

For context on Manafort’s 47 months in prison, my client yesterday was offered 36-72 months in prison for stealing $100 worth of quarters from a residential laundry room.

Anecdotes, however, run the risk of misleading if they are not representative. The Bureau of Justice Statistics just released Time Served in State Prison 2016. Stealing laundry quarters sounds like larceny (no break in). The average time served for larceny was 17 months and the median time served was 11 months.

Hechinger also notes this outrageous case:

15 years in prison for drug possession. You shouldn’t need more info than that to be outraged. But then learn: Juanita is a mother of 6. Her 18 year old is now head of household. Raising 5 kids. Crime is not even a felony in Oklahoma anymore.

The average time served for drug possession was 15 months and the median time 10 months. Arguably too long but a far cry from 15 years.

For a serious violent crime like robbery, taking property by force or threat of force, the average time served was considerably higher, 4.7 years and the median time served 3.2 years.

You can see the table below for more data. Judge for yourselves, but for most crimes mean and median time served don’t seem to me to be obviously too high. Moreover, keep in mind that most crimes do not result in an arrest let alone a conviction or time served.

In 2017, for example, victims reported 2,000,990 serious violent crimes (rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault). In the same year there were approximately 446,510 arrests for these crimes (crime definitions may not line up exactly). In other words, the chance of being arrested for a serious violent crime was only 22%. Data on convictions are harder to obtain but convictions are far fewer than arrests. In 2006 (most up-to-date data I could find but surely lower today) there were 175,500 convictions for serious violent crimes. Thus, considerably fewer than 10% of violent crimes result in a conviction (175,500/2,000,990=8.7%).

Put differently, the expected time served for a serious violent crime is less than 5 months*. Do you want to reduce expected time served? What I would like to do is put more police on the street to increase the certainty of arrest and conviction. If we double the conviction rate, I’d happily halve time served.

I support decriminalization of many crimes, shorter sentences for some crimes and fewer scarlet letter punishments. I want to reduce bias and variability in the criminal justice system. But I do not want to return to the crime rates of the past. Even as crime rates fall, we should be careful about declaring the war won and going home. We are under policed in the United States and despite anecdotes that rightly shock the conscience, average time served is not that high, especially given very low arrest and conviction rates.

* Using the normalized percent of total releases for rape, robbery and assault to form the weighted average. Corrected from an early version that said 14 months.

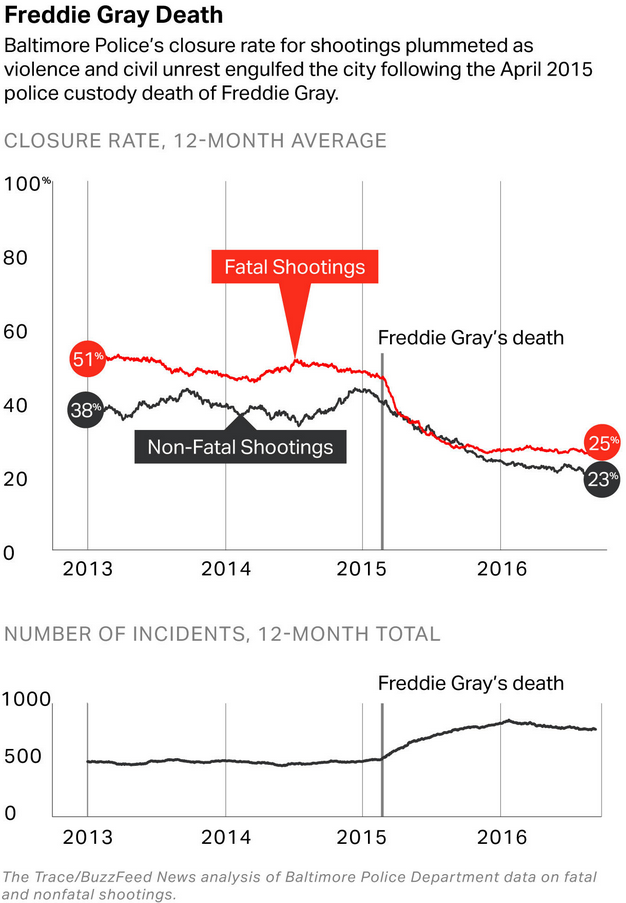

Unsolved Shootings are Rising

In 2015, I documented that crime in Baltimore was rising rapidly as police resources became stretched as they dealt with riots and anger following the death of Freddie Gray. I warned that the city could tip into a permanently higher crime rate.

In 2015, I documented that crime in Baltimore was rising rapidly as police resources became stretched as they dealt with riots and anger following the death of Freddie Gray. I warned that the city could tip into a permanently higher crime rate.

It’s now become clear that is exactly what happened as an investigative report by The Trace reveals:

Instead of getting backup, detectives were pulled from their cases, sometimes for days at a time, to help quell the violence. By 2016, homicide investigators cumulatively spent 10,000 hours working riot duty and patrol rather than tracking down murderers…

In the ensuing months, Baltimore’s closure rate for shootings dropped to 25 percent, the lowest in recent history. More than 1,100 cases from 2015 and 2016 alone remained unsolved by the following summer.

As the closure rate fell, the number of shootings increased (see data at right).

It’s not just Baltimore, however:

The crisis of unsolved shootings isn’t confined to cash-strapped cities like Baltimore, but also hits some of America’s most affluent metropolises. In 2016, Los Angeles made arrests for just 17 percent of gun assaults, and Chicago for less than 12 percent. The same year, San Francisco managed to make arrests in just 15 percent of the city’s nonfatal shootings. In Boston, the figure was just 10 percent.

Crime is lower today than in the past but we are in danger of becoming complacent. The rate of unsolved crimes is very high and in some cities it is soaring. Any city with an arrest rate for assaults of 15% is primed for a crime wave.

We need more police as well as better policing.

Addendum: I wonder how many of these cities are still devoting significant resources to marijuana busts?

“Get Out of Jail Free” Cards

In the movies I’ve seen people who try to get out of a traffic ticket by telling the police officer they made a donation to the policeman’s ball, but those were comedies. I had no idea that not only does this exist there are official cards. In fact, the police in New York are livid that the number of cards is being limited:

The city’s police-officers union is cracking down on the number of “get out of jail free” courtesy cards distributed to cops to give to family and friends.

Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association boss Pat

Lynch slashed the maximum number of cards that could be issued to current cops from 30 to 20, and to retirees from 20 to 10, sources told The Post.

The cards are often used to wiggle out of minor trouble such as speeding tickets, the theory being that presenting one suggests you know someone in the NYPD.

The rank and file is livid.

“They are treating active members like s–t, and retired members even worse than s–t,” griped an NYPD cop who retired on disability. “All the cops I spoke to were . . . very disappointed they couldn’t hand them out as Christmas gifts.”

A Christmas gift of institutionalized corruption.

Here’s another article on these cards which just gets all the more stunning.

First, there are tiers of cards. Silver cards are the highest honor given to citizens. It’s almost universally honored by officers, and can also help save money on insurance. Gold PBA cards are only given to police officers and their families. You’d be hard-pressed finding a cop who won’t honor a gold card.

Gold and silver cards! It gets better. You can buy these cards on eBay. Here’s a gold New Jersey card on sale for $114. A silver “family member” shield goes for $299. Some of these are probably fake. The gold and silver are rare but remember, cops get 20 to 30 regular cards so you can see why they might be upset at losing them.

The regular cards have become more common as NYC hires more police. The union may in fact be trying to bump up its monopoly profit by restricting supply.

The cards don’t just go to family members. The rot is deep:

Union officials say the cards are also public relations tools and tokens of appreciation handed out to politicians, judges, lawyers, businessmen, civil service workers and members of the news media.

A retired police officer on Quora explains how the privilege is enforced:

The officer who is presented with one of these cards will normally tell the violator to be more careful, give the card back, and send them on their way.

…The other option is potentially more perilous. The enforcement officer can issue the ticket or make the arrest in spite of the courtesy card. This is called “writing over the card.” There is a chance that the officer who issued the card will understand why the enforcement officer did what he did, and nothing will come of it. However, it is equally possible that the enforcement officer’s zeal will not be appreciated, and the enforcement officer will come to work one day to find his locker has been moved to the parking lot and filled with dog excrement.

He’s not kidding. Here is what seems like a real police officer on a cop chat room (from Mimesis law)

It’s important for me to get in touch with shield [omitted] and ask him why he felt it necessary to say “I’m not even going to look at that” to my PBA card and proceed [sic] to write a speeding ticket on the Bronx River Parkway yesterday afternoon to my fukking WIFE!!!!!!!!!!!!

I’ll show him the courtesy he so sorely lacks by not posting his name on a public forum.

Any help would be appreciated. Please inbox me.

I will find you.

I find these cards especially odious as more and more police are funding themselves through fines and forfeitures. Discriminatory taxation increases the tax rate. It’s one rule for the ruler and another for the ruled.

The cards are not a secret but I agree with my colleague Mark Koyama who remarked:

Sometimes you find out something about the country you live in that makes it appear little better than a corrupt, tinpot, banana republic.

Crime Imprisons and Kills

…the most disadvantaged people have gained the most from the reduction in violent crime.

Though homicide is not a common cause of death for most of the United States population, for African-American men between the ages of 15 and 34 it is the leading cause, which means that any change in the homicide rate has a disproportionate impact on them. The sociologist Michael Friedson and I calculated what the life expectancy would be today for blacks and whites had the homicide rate never shifted from its level in 1991. We found that the national decline in the homicide rate since then has increased the life expectancy of black men by roughly nine months.

…The everyday lived experience of urban poverty has also been transformed. Analyzing rates of violent victimization over time, I found that the poorest Americans today are victimized at about the same rate as the richest Americans were at the start of the 1990s. That means that a poor, unemployed city resident walking the streets of an average city today has about the same chance of being robbed, beaten up, stabbed or shot as a well-off urbanite in 1993. Living in poverty used to mean living with the constant threat of violence. In most of the country, that is no longer true.

That’s Patrick Sharkey writing in the New York Times.

More police on the street is one cause, among many, of lower crime. It’s important in the debate over better policing that we not lose sight of the value of policing. Given the benefits of reduced crime and the cost of police, it’s clear that U.S. cities are under policed (e.g. here and here). We need better policing–including changes in laws–so that we can all be comfortable with more policing.

What Was Gary Becker’s Biggest Mistake?

The econometrician Henri Theil once said “models are to be used but not to be believed.” I use the rational actor model for thinking about marginal changes but Gary Becker really believed the model. Once, at a dinner with Becker, I remarked that extreme punishment could lead to so much poverty and hatred that it could create blowback. Becker was having none of it. For every example that I raised of blowback, he responded with a demand for yet more punishment. We got into a heated argument. Jim Buchanan and Bryan Caplan approached from the other end of the table and joined in.  It was a memorable evening.

It was a memorable evening.

Becker isn’t here to defend himself on the particulars of that evening but you can see the idea in his great paper, Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach. In a famous section he argues that an optimal punishment system would combine a low probability of being punished with a high level of punishment if caught:

If the supply of offenses depended only on pf—offenders were risk neutral — a reduction in p “compensated” by an equal percentage increase in f would leave unchanged pf…

..an increased probability of conviction obviously absorbs public and private resources in the form of more policemen, judges, juries, and so forth. Consequently, a “compensated” reduction in this probability obviously reduces expenditures on combating crime, and, since the expected punishment is unchanged, there is no “obvious” offsetting increase in either the amount of damages or the cost of punishments. The result can easily be continuous political pressure to keep police and other expenditures relatively low and to compensate by meting out strong punishments to those convicted.

We have now tried that experiment and it didn’t work. Beginning in the 1980s we dramatically increased the punishment for crime in the United States but we did so more by increasing sentence length than by increasing the probability of being punished. In theory, this should have reduced crime, reduced the costs of crime control and led to fewer people in prison. In practice, crime rose and then fell mostly for reasons other than imprisonment. Most spectacularly, the experiment with greater punishment led to more spending on crime control and many more people in prison.

Why did the experiment fail? Longer sentences didn’t reduce crime as much as expected because criminals aren’t good at thinking about the future; criminal types have problems forecasting and they have difficulty regulating their emotions and controlling their impulses. In the heat of the moment, the threat of future punishment vanishes from the calculus of decision. Thus, rather than deterring (much) crime, longer sentences simply filled the prisons. As if that weren’t bad enough, by exposing more people to criminal peers and by making it increasingly difficult for felons to reintegrate into civil society, longer sentences increased recidivism.

Instead of thinking about criminals as rational actors, we should think about criminals as children. In this light, consider the “Becker approach” to parenting. Punishing children is costly so to reduce that cost, ignore a child’s bad behavior most of the time but when it’s most convenient give the kid a really good spanking or put them in time out for a very long time. Of course, this approach leads to disaster–indeed, it’s precisely this approach that leads to criminality in later life.

So what is the recommended parenting approach? I don’t want to get into a debate over spanking, timeouts, and reasoning but one thing all recommendations have in common is that the consequences for inappropriate behavior should be be quick, clear, and consistent. Quick responses help not just because children have “high discount rates” (better thought of as difficulty integrating their future selves into a consistent whole but “high discount rates” will do as short hand) but even more importantly because a quick response helps children to understand the relationship between behavior and consequence. Prior to Becker there was Becaaria and in Beccarian theory, people must learn to associate crime with punishment. When responses aren’t quick, children, just like scientists, have difficulty learning cause and effect. Quick is thus one way of lowering cognitive demands and making consequences clear.

Animals can learn via conditioning but people can do much better. If you punish the child who steals cookies you get less cookie stealing but what about donuts or cake? The child who understands the why of punishment can forecast consequences in novel circumstances. Thus, consequences can also be made clear with explanation and reasoning. Finally, consistent punishment, like quick punishment, improves learning and understanding by reducing cognitive load.

Quick, clear and consistent also works in controlling crime. It’s not a coincidence that the same approach works for parenting and crime control because the problems are largely the same. Moreover, in both domains quick, clear and consistent punishment need not be severe.

In the economic theory, crime is in a criminal’s interest. Both conservatives and liberals accepted this premise. Conservatives argued that we needed more punishment to raise the cost so high that crime was no longer in a criminal’s interest. Liberals argued that we needed more jobs to raise the opportunity cost so high that crime was no longer in a criminal’s interest. But is crime always done out of interest? The rational actor model fits burglary, pick-pocketing and insider trading but lots of crime–including vandalism, arson, bar fights and many assaults–aren’t motivated by economic gain and perhaps not by any rational interest.

Here’s a simple test for whether crime is in a person’s rational interest. In the economic theory if you give people more time to think carefully about their actions you will on average get no change in crime (sometimes careful thinking will cause people to do less crime but sometimes it will cause them to do more). In the criminal as poorly-socialized-child theory, in contrast, crime is often not in a person’s interest but instead is a spur of the moment mistake. Thus, even a small opportunity to reflect and consider will result in less crime. As one counselor at a juvenile detention center put it:

20 percent of our residents are criminals, they just need to be locked up. But the other 80 percent, I always tell them – if I could give them back just ten minutes of their lives, most of them wouldn’t be here.

Cognitive behavioral therapy teaches people how to act in those 10 minutes–CBT is not quite as simple as teaching people to count to ten before lashing out but it’s similar in spirit, basically teaching people to think before acting and to revise some of their assumptions to be more appropriate to the situation. Randomized controlled trials and meta-studies demonstrate that CBT can dramatically reduce crime.

Cognitive behavioral therapy teaches people how to act in those 10 minutes–CBT is not quite as simple as teaching people to count to ten before lashing out but it’s similar in spirit, basically teaching people to think before acting and to revise some of their assumptions to be more appropriate to the situation. Randomized controlled trials and meta-studies demonstrate that CBT can dramatically reduce crime.

Cognitive behavioral therapy runs the risk of being labeled a soft, liberal approach but it can also be thought of as remedial parenting which should improve understanding and appreciation among conservatives. More generally, it’s important that crime policy not be forced into a single dimension running from liberal to conservative, soft to tough. Policing and prisons, for example, are often lumped together and placed on this single, soft to tough dimension when in fact the two policies are different. I favor more police on the street to make punishment more quick, clear, and consistent. I would be much happier with more police on the street, however, if that policy was combined with an end to the “war on drugs”, shorter sentences, and an end to brutal post-prison policies that exclude millions of citizens from voting, housing, and jobs.

Let’s give Becker and the rational choice theory its due. When Becker first wrote many criminologists were flat out denying that punishment deterred. As late as 1994, for example, the noted criminologist David Bayley could write:

The police do not prevent crime. This is one of the best kept secrets of modern life. Experts know it, the police know it, but the public does not know it. Yet the police pretend that they are society’s best defense against crime. This is a myth

Inspired by Becker, a large, credible, empirical literature–including my own work on police (and prisons)–has demonstrated that this is no myth, the police deter. Score one for rational choice theory. It’s a far cry, however, from police deter to twenty years in prison deters twice as much as ten years in prison. The rational choice theory was pushed beyond its limits and in so doing not only was punishment pushed too far we also lost sight of alternative policies that could reduce crime without the social disruption and injustice caused by mass incarceration.

Dangerous jobs

More police officers die each year in patrol car crashes than at the

hands of criminals, and most of the time the accidents occur when the

officers are not speeding to an emergency, a new study says.But

the researchers say the number of deaths could be reduced if police

departments did more to encourage officers to use seat belts. The

authors of the report, in The Journal of Trauma, reviewed hundreds of

police car accidents across the country from 1997 to 2001 and also

found that officers involved in crashes were 2.6 times as likely to be

killed if they were not wearing seat belts…Dr. Jehle said that officers who were interviewed for the study were

surprised to find that about 60 percent of the deaths occurred during

routine driving. They tend to view the car as a haven. "It’s their

office," he said. "They’re in it all the time."

Here is The New York Times story.

Against Broken Windows

James Q. Wilson’s broken windows theory is simple: broken windows, or other symbols of public disorder, invite crime. Thus, if you clean up the neighborhood, crime should go away. The NY Times discusses research conducted by Felton Earls, Rob Samson, Steve Raudenbush and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn testing this theory. They drove an SUV through *thousands* of Chicago streets and recorded with a video camera just about everything that was visible on the street – garbage, loitering, grafitti, etc. They also had data on crime and the attitudes and behavior of residents. Analysis of data showed that public signs of disorder such as garbage were not linked to crime. Instead, concentrated poverty and the willingness of residents to self-police (“collective efficacy”) explained the incidence of crime. The Times quotes Earls:

“If you got a crew to clean up the mess,” Dr. Earls said, “it would last for two weeks and go back to where it was. The point of intervention is not to clean up the neighborhood, but to work on its collective efficacy. If you organized a community meeting in a local church or school, it’s a chance for people to meet and solve problems.

“If one of the ideas that comes out of the meeting is for them to clean up the graffiti in the neighborhood, the benefit will be much longer lasting, and will probably impact the development of kids in that area. But it would be based on this community action – not on a work crew coming in from the outside.”

This point should be taken to heart by all students of crime. Yes, of course, police are necessary for public order and safety. But the police are finite resource – they can’t possibly monitor every street and corner. Thus, on a fundamental level, public safety comes from a community’s ability to regulate itself. The next time you hear a call for more police, or more prisons, or more public works, think about this insight.

Is there Hope for Evidence-Based Policy?

Vital City magazine and the Niskanen Center’s Hypertext have a special issue on the prospects for “evidence-based policymaking.” The issue takes as its starting point, Megan Stevenson’s Cause, effect, and the structure of the social world, a survey of RCTs in criminology which concludes that the vast majority of interventions “have little to no lasting effect.” The issue features responses from John Arnold, Jonathan Rauch, Anna Harvey, Aaron Chalfin, Jennifer Doleac, myself, and others. It’s an excellent issue.

My contribution focuses on the difference between changing preferences versus constraints. Here’s one bit:

Some other programs that Stevenson mentions elsewhere are also not predominantly constraint- or incentive-changing. Take, for example, the many papers estimating the effect of imprisonment on the post-release behavior of criminal defendants via the random selection of less and more lenient judges. At first, it may seem absurd to say that imprisonment is not about incentives. Isn’t deterrence the ne plus ultra of incentives? Yes, but the economic theory of deterrence, so-called general deterrence, is rooted in the anticipation of consequences — the odds before the crime. By the sentencing stage, we’re merely observing where the roulette wheel stopped. Criminals factor in the likelihood of capture as just another cost of doing business. Thus, the economic theory of deterrence predicts high rates of recidivism, as the calculus that justified the initial crime remains unchanged after punishment. To be sure, imprisonment might change behavior for all kinds of reasons. Maybe inmates learn that they underestimated the unpleasantness of prison, but perhaps they improve their criminal skills while in prison or join a gang, or perhaps the stain of a criminal record reduces the prospect of legitimate employment. Thus, the study of imprisonment’s effects on criminal defendants is intriguing, but it’s not testing deterrence or incapacitation, on which we have built a body of work with clear predictions.

Indeed, on Stevenson’s list only hot-spot policing is a clear example of changing constraints. It is perhaps not coincidental that hot-spot policing is one of the few interventions that Stevenson acknowledges “leads to a small but statistically significant decrease in reported crime in the areas with increased policing.” While I do not begrudge Stevenson her interpretation, other people shade the total evidence differently. Here, for example, is the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy, in my experience a rather tough-minded and empirically rigorous organization not easily swayed by compelling narratives:

As the National Research Council review of police effectiveness noted, “studies that focused police resources on crime hot spots provided the strongest collective evidence of police effectiveness that is now available.” A Campbell systematic review by Braga et al. comes to a similar conclusion; although not every hot spots study has shown statistically significant findings, the vast majority of such studies have (20 of 25 tests from 19 experimental or quasi-experimental evaluations reported noteworthy crime or disorder reductions), suggesting that when police focus in on crime hot spots, they can have a significant beneficial impact on crime in these areas. As Braga concluded, “extant evaluation research seems to provide fairly robust evidence that hot spots policing is an effective crime prevention strategy.”

Indeed, I argue that most of the programs that Stevenson shows failed, tried to change preferences while those that succeeded tend to focus on changing constraints. There are lessons for future policy and funding. Read the whole thing.