Results for “multiplier” 112 found

The incidence of the ACA mandates

Here is Mark Pauly, with Adam Leive and Scott Harrington (NBER), this is part of the abstract:

We find that the average financial burden will increase for all income levels once insured. Subsidy-eligible persons with incomes below 250 percent of the poverty threshold likely experience welfare improvements that offset the higher financial burden, depending on assumptions about risk aversion and the value of additional consumption of medical care. However, even under the most optimistic assumptions, close to half of the formerly uninsured (especially those with higher incomes) experience both higher financial burden and lower estimated welfare; indicating a positive “price of responsibility” for complying with the individual mandate. The percentage of the sample with estimated welfare increases is close to matching observed take-up rates by the previously uninsured in the exchanges.

I’ve read so many blog posts taking victory laps on Obamacare, but surely something is wrong when our most scientific study of the question rather effortlessly coughs up phrases such as “but most uninsured will lose” and also “Average welfare for the uninsured population would be estimated to decline after the ACA if all members of that population obtained coverage.” The simple point is that people still have to pay some part of the cost for this health insurance and a) they were getting some health care to begin with, and b) the value of the policy to them is often worth less than its subsidized price.

You will note that unlike say the calculation of the multiplier in macroeconomics, the exercises in this paper are relatively straightforward. They also show that people exhibit a fairly high degree of economic rationality when it comes to who signs up and who does not.

It has become clearer what has happened: members of various upper classes have achieved some notion of “universal [near universal] coverage,” while insulating their own medical care from most of the costs of this advance. Those costs largely have been placed on the welfare of…the other members of the previously uninsured. So we’ve moved from being a country which doesn’t care so much about its uninsured to being…a country which doesn’t care so much about its (previously) uninsured. I guess countries just don’t change that rapidly, do they?

I fully understand that Obamacare has survived the ravages of the Republican Party, and it was barely attacked in the recent series of debates, and thus it is permanently ensconced, and that no better politically feasible alternative has been proposed. At this point, the best thing to do is to improve it from within. Still, there are good reasons why it will never be so incredibly popular.

An event study of the recent UK election

Via Jasper Plan, Jonathan K. Pedde has a new paper on this:

Standard zero-lower-bound New Keynesian models generate large fiscal multipliers and expansionary negative supply shocks. Thus, according to these models, a political party that implements fiscal contraction coupled with policies to increase aggregate supply should unambiguously cause economic contraction, compared to a party that implements the opposite policies. I test this prediction using high-frequency prediction- and financial-market data from the night of the 2015 U.K. election, which featured two such parties. By analysing financial-market movements caused by clearly exogenous changes in expectations about the election winner, I find that market participants expected higher equity prices and a stronger exchange rate under a Conservative Prime Minister than under a Labour P.M. There were little to no partisan differences in interest rates, expected inflation, or commodity prices. These results cast doubt on the empirical validity of zero-lower-bound New Keynesian models.

And here is Noah on the UK, he is right, and I call this one pretty much settled.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Truly practical ethics. I love this piece.

2. Orlando Patterson on inner cities.

3. A South L.A. partial ban on fast food restaurants doesn’t seem to have helped obesity.

4. Jason Furman on poverty programs that work.

5. When did America overtake the UK in terms of productivity?

6. The facts of economic growth (NBER).

Assorted links

1. Scott Sumner on Keynesian excuses.

2. Alan Krueger working for Uber. And dating average is over. And rendering Tyler Cowen obsolete.

3. Newspapers are still deep in a financial hole.

4. Divorce machine gun markets in everything. And Croatia wants to peg to the Swiss franc (!) for mortgage protection.

5. Department of Uh-Oh: more competition leads to higher antibiotic prescription rates.

6. Matthew Slaughter is now Dean of Dartmouth business school.

7. The legal system that is German. They got the ruling right, I say.

8. Paul Krugman’s estimate: “So, Draghi’s big announcement seems to have raised expected European inflation by one-fifth of a percentage point.” Alternatively, Daniel Davies on why QE might prove effective.

Alesina and co-authors respond on European fiscal austerity

They have a new NBER working paper on this topic, here is one key part of the abstract:

Fiscal adjustments based upon cuts in spending appear to have been much less costly, in terms of output losses, than those based upon tax increases. The difference between the two types of adjustment is very large. Our results, however, are mute on the question whether the countries we have studied did the right thing implementing fiscal austerity at the time they did, that is 2009-13.

They also consider, and cannot reject, the possibility that the output declines of recent times were due to additional negative variables, such as credit crunches, rather than higher values for the fiscal multiplier.

I predict this paper will be ignored rather than responded to. For a while now it has been the practice to criticize “austerity” rather than to disaggregate the policies, or describe them with greater specificity, even though that is easy to do. And it is incorrect to describe this paper as defending austerity, rather I read it as being anti-tax hike, and suggesting that “austerity” is not a very useful concept.

There is an ungated version of the paper here.

Assorted links

1. Argentina’s President Kirchner adopts Jewish godson to prevent him from being turned into a werewolf. Before 2009, this privilege was restricted to Catholics only.

2. Barbie doll prices vary by job.

3. Are there too many “Best of” lists?

4. What is the “eyeball evidence” for the multiplier?

5. A prospective (and idiosyncratic) review of the AEA meetings.

6. Ezra Klein interviews Paul Krugman.

7. Many animals do not take sunk costs into account. And my 2012 column on Greece and the eurozone.

Optimal Journal Submission Strategy

Kevin Vallier, a philosopher, considers on Facebook the optimal journal submission strategy:

I was implicitly assuming the best strategy was to start with the best journals, receive rejections, and then work my way down, lest my piece get accepted by a sub-par journal first. But now I’m thinking it may make more sense to start from “the bottom” or at least mid-tier journals and work my way “up” if I can assume that my pieces will generally be rejected several times, even by the mid-tier journals. I think I was overestimating the risk of publishing my work in mid-tier journals and underestimating how much rejections can improve the quality of the paper. In light of this, I want to construct a “journal ladder” that political philosophers and political theorists can “climb” towards the best journals.

Let’s put some numbers on this to see what makes sense. The expected utility from submitting to a high quality journal first is:

HighFirst = Ph* HV + (1 – Ph)*(Pl*mult)* 1

The first term, Ph*HV is the probability of acceptance at a high quality journal times the value of acceptance at a high quality journal. If the paper is rejected, which happens with probability (1-Ph), then you go to a low-quality journal where the paper is accepted with probability Pl times the multiplier which you get because of suggestions and comments from the referees at the high quality journal. The value of the low-quality journal is set to 1 so HV>=1.

Now what about low first:

LowFirst = Pl*1 + (1 – Pl) (Ph*mult)*HV

if you submit to the low quality journal and are accepted you get Pl*1, if the low quality journal rejects which will happen with probability (1-Pl) you submit to the high quality journal which accepts with probability Ph*mult and if accepted you get HV.

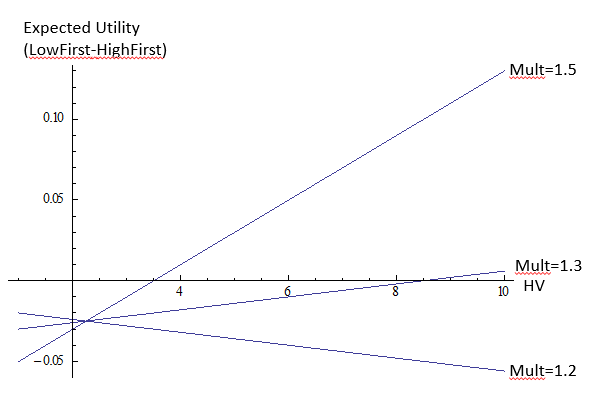

Now let’s put some numbers on this. The probability of acceptance at a high quality journal is 5-10%. The rate at the AER in recent years, for example, has been about 7.5%. Let’s say 10% and for a low-quality journal 20%. These rates are conditional on being the type of paper that is submitted to the AER not any random paper. (These rates are also reasonable for philosophy journals.). What’s the value of HV, the high quality journal relative to the low quality journal? Let’s say between 1 (equally valuable) and 10. And the multiplier? 1.5 would be very generous. 1.1 might be reasonable on average, 1.2 if you are lucky. Given these numbers let’s consider LowFirst-HighFirst so positive numbers mean that the LowFirst strategy is better, negative numbers that the HighFirst strategy is better. Here’s what we get:

The way to read this is that if the multiplier is a hefty 1.5 then LowFirst is superior to HighFirst if a high quality journal has a value of at least 3.5 (relative to the low quality journal at 1). If the multiplier is 1.3, however, then LowFirst is optimal only if the high quality journal is more than 8 times as valuable as the low-quality journal. And for a multiplier of 1.2 LowFirst is never optimal.

Thus the LowFirst strategy is better the higher the relative value of a high-quality journal, the bigger the multiplier and also the lower the acceptance rate at the low quality journal . The lower the acceptance rate at the low-quality journal the lower the cost of submitting it there in order to earn the multiplier.

I conclude that the high-value first strategy is usually optimal. All the more so since there are good substitutes for submitting to a low quality journal. Namely, submit the paper to a conference, circulate the paper to friends, enemies (especially) and others to get comments. The multiplier with this approach will be at least as large as with the submission approach and the opportunity cost will be lower.

Import Competition and the Great U.S. Employment Sag of the 2000s

In the new NBER paper on this topic by Daron Acemoglu, David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, and Brendan Price, we see the evidence for this proposition piling up:

Even before the Great Recession, U.S. employment growth was unimpressive. Between 2000 and 2007, the economy gave back the considerable gains in employment rates it had achieved during the 1990s, with major contractions in manufacturing employment being a prime contributor to the slump. The U.S. employment “sag” of the 2000s is widely recognized but poorly understood. In this paper, we explore the contribution of the swift rise of import competition from China to sluggish U.S. employment growth. We find that the increase in U.S. imports from China, which accelerated after 2000, was a major force behind recent reductions in U.S. manufacturing employment and that, through input-output linkages and other general equilibrium effects, it appears to have significantly suppressed overall U.S. job growth. We apply industry-level and local labor market-level approaches to estimate the size of (a) employment losses in directly exposed manufacturing industries, (b) employment effects in indirectly exposed upstream and downstream industries inside and outside manufacturing, and (c) the net effects of conventional labor reallocation, which should raise employment in non-exposed sectors, and Keynesian multipliers, which should reduce employment in non-exposed sectors. Our central estimates suggest net job losses of 2.0 to 2.4 million stemming from the rise in import competition from China over the period 1999 to 2011. The estimated employment effects are larger in magnitude at the local labor market level, consistent with local general equilibrium effects that amplify the impact of import competition.

There are more details in this version of the paper than in an earlier version cited on this blog. Here is my related column on economic contraction, from a few days back.

Chris House on stimulus spending

These points have been far too often forgotten:

Even if the multiplier is substantially above 1, it is not obvious that stimulus spending is a good idea. The reason is that we are not trying to maximize output and employment – we are trying to maximize overall social well-being. At a basic level, the idea behind stimulus spending is that the government will spend money on stuff that it wouldn’t have purchased if we weren’t in a recession. The classic caricature of stimulus spending is the idea of paying a worker to dig a hole and then paying another worker to fill the hole in. This type of stimulus spending will increase employment and GDP but it won’t really enhance social welfare. True, we might get the beneficial effects of the stimulus but we could achieve that by simply giving the workers the money without requiring that they dig the holes. If we simply give out the money, GDP increases by less but social well-being goes up by more since the work effort and time wasn’t required.

Even though the Keynesian hole-digging example is silly, the same argument can be applied to any type of government spending. If a project doesn’t meet the basic cost / benefit test, then it shouldn’t be funded, regardless of the need for stimulus. Of course, one form of fiscal stimulus used in the ARRA was providing funds to state governments so they could maintain services that they would normally provide. This is perfectly sound policy because it is allowing the government to continue to fund projects that (presumably) do pass the cost / benefit calculation. If the social value of a government project exceeds its social cost then we should continue to fund the project whether we are in a recession or not. If the social value falls short of the social cost then, even if the economy is in “dire need” of stimulus we should not fund it. If we really need stimulus but there are no socially viable projects in the queue then the government should use tax cuts. Tax cuts can be adopted quickly and aggressively and, unlike spending initiatives, apply to virtually all Americans.

There are other “legitimate” reasons for the government to expand spending during a recession. The most obvious is that many things are relatively cheap in recessions. Reductions in manufacturing and construction employment may lower the cost for government projects. But again, this decision can be made on a simple cost / benefit basis. If prices fall because of a recession and this makes some projects socially viable as a result, then it’s perfectly correct for the government to fund those projects.

If it makes people feel better we could re-label tax cuts as spending. I could pay people $200 to look around for better paying jobs. This would be counted as $200 of job searching services purchased by the government but in reality, the money would be essentially the same as a tax cut.

The full post is here.

What was the scope for British Keynesian policies in the 1930s?

There is a new paper by Nicholas Crafts & Terence Mills in the December 2013 Journal of Economic History, entitled Rearmament to the Rescue? New Estimates of the Impact of “Keynesian” Policies in 1930s’ Britain. The abstract is here:

We report estimates of the fiscal multiplier for interwar Britain based on quarterly data, time-series econometrics, and “defense news.” We find that the government expenditure multiplier was in the range 0.3 to 0.8, much lower than previous estimates. The scope for a Keynesian solution to recession was less than is generally supposed. We find that rearmament gave a smaller boost to real GDP than previously claimed. Rearmament may, however, have had a larger impact than a temporary public works program of similar magnitude if private investment anticipated the need to add capacity to cope with future defense spending.

You will note that previous estimates of the multiplier for this period are much higher, but this conclusion is based on a new quarterly gdp series for the UK and also on identified “defense shocks,” drawn from The Economist magazine. At this time, by the way, Great Britain was very close to the zero lower bound and had significant unemployed resources. I am not sure I would push this as “the correct answer,” but rather as a more general lesson about the fragility of our knowledge in this area.

The published (gated) version of the paper is here. There are ungated versions here.

Robert J. Barro on aggregate demand

There has been a recent kerfluffle over whether Robert Barro rejects the notion of aggregate demand, which he had written with quotation marks as “aggregate demand.” Scott Sumner surveys the back and forth.

I say use The Google to find out what Barro really thinks and indeed he has written a whole piece on the topic (jstor), namely “The Aggregate-Supply/Aggregate Demand Model,” from the mid 1990s, and here is the abstract:

In recent years, many macroeconomic textbooks at the principles and intermediate levels have adopted the aggregate-supply/aggregate-demand (AS-AD) frame- work [Baumol and Blinder, 1988, Ch. 11; Gordon, 1987, Ch. 6; Lipsey, Steiner, and Purvis, 1984, Ch. 30; Mankiw, 1992, Ch. 11]. The objective was to allow for supply shocks in a Keynesian framework and to generate more satisfactory predictions about the behavior of the price level. The main point of this paper is that the AS-AD model is unsatisfactory and should be abandoned as a teaching tool.

In one version of the aggregate-supply curve, the components of the AS-AD model as usually used are contradictory. An interpretation of the model to eliminate the logical inconsistencies makes it a special case of rational-expectations macro models. In this mode, the model has no Keynesian characteristics and delivers the policy prescriptions that are familiar from the rational-expectations literature.

An alternative version of the aggregate-supply curve leads to what used to be called the complete Keynesian model: the goods market clears but the labor market has chronic excess supply. This model was rejected long ago for good reasons and should not be resurrected now.

If you read the paper, you will see three things. First, Barro is fully aware of “AD-like” phenomena and does not reject that notion. Second, Barro seems to prefer the IS-LM model to AS-AD, albeit with some caveats about possible false predictions of IS-LM and also noting in footnote two that he prefers his own presentation in his 1993 text. Third, Barro’s criticism is (whether you agree or not) that AD-AS collapses too readily into standard rational expectations models and doesn’t really provide an independent foundation for sticky price macroeconomics. In a nutshell “The AS-AD model is logically flawed as usually presented because its assumption that the price level clears the goods market is inconsistent with the Keynesian underpinnings for the aggregate-demand curve.”

Krugman had written this:

If you read Barro’s piece, what you see is a blithe dismissal of the whole notion that economies can ever suffer from am inadequate level of “aggregate demand” — the scare quotes are his, not mine, meant to suggest that this is a silly, bizarre notion, in conflict with “regular economics.”

I believe that is not a good characterization of Barro’s views and it is also an object lesson in the importance of the Ideological Turing Test. I would cite not only this piece, but also forty years of journal articles, many of which study the importance of nominal shocks and demand, albeit without (in general) using textbook AD-AS terminology. Indeed, Barro working with Herschel Grossman is one of the founding fathers of quantity-constrained Keynesian sticky-price macro and he is still citing this work favorably in his mid-1990s piece; see for instance Barro and Grossman (1971, 1974) and also their book from 1976: “This is a textbook on macroeconomic theory that attempts to rework the theory of macroeconomic relations through a re-examination of their microeconomic foundations. In the tradition of Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money…”

On the UI issue, I would note that the multiplier from transfers is likely unimpressive relative to the multiplier from government consumption.

The correct framing of the Irish economic dilemma: guarantees vs. austerity

The policy of No Bondholder Left Behind, on which the European Central Bank insisted, has been staggeringly expensive. To put it in perspective, the European Union has just agreed to create a fund of $75 billion to deal with all future banking crises in its member states. Tiny Ireland has spent $85 billion bailing out its own banks [TC: with more to come, and note the bailouts are more to the creditors than to the banks themselves].

That is from Fintan O’Toole, who wrote a good paragraph there. Yet I do not agree with all of his framing, as he too often presents the Irish dilemma as a debate about austerity.

Let’s say that I, Tyler Cowen, accepted a debt obligation of $5 million, and in order to make some of the interest payments I cut back my spending on food, drink, and Amazon.com and my energy then so weakened that I could never write another book again. That would be bad for my income, since even at the individual level there may be “multiplier effects.” (Please note that by introducing this multiplier assumption I am restoring a kind of parity between the individual and collective cases, no need to snark on this point.)

One way to look at that episode would be to soft pedal the initial guarantee of the debt and focus on the consequences of my “austerity,” and attack the cuts in expenditure, while blaming the new commitments I took on only in passing. I would say that is a misleading interpretation of what happened.

A better way to look at the episode is to focus on the wisdom or foolishness of the guarantee of the $5 million. I would say such a guarantee would be foolish, either for me or for the much larger bank debt bailouts made by the Irish.

Another good and indeed scientific way to frame the question is to take the debt guarantee as given (albeit possibly mistaken), and ask whether my spending cuts should come quickly or be spread out more slowly over time. That is a perfectly fair question to ask and we should not expect the correct answer to be obvious, although of course postponing spending cuts would have meant, for the Irish, borrowing at double digit rates and also risking a full scale “sudden stop.” Furthermore, if we observe speedy rather than gradual spending cuts, the misery of the results does not in any way settle the question of which speed of adjustment would have been better. Pointing out “this isn’t going so well” does not — at all — militate against the speedier path of cuts or for that matter militate against “austerity.” At most it is an argument against the initial guarantee of debt (and even then we are not witnessing the counterfactual).

Nor does changing the topic by asserting “Germany should give Tyler the money” help us settle the right course of action in a world where Germany has no such intention. The same can be said for “Germany should tolerate three percent inflation,” even if that claim is correct.

These points are not even Econ 101, rather they are Propaedeutic to Logic.

Overall, it is amazing how the single largest extension in the responsibilities and fiscal obligations of the Irish state — ever — has been turned into a PR defeat for the idea of fiscal conservatism.

If nothing else, that is testament to how powerful an incorrect message can be if it is repeated enough times and without the proper context.

Addendum: Here is further information on the recent Irish ritual chess murder — Bishop takes lung? — involving by the way an aggressive Sicilian.

Dupor and Li on the Missing Inflation in the New-Keynesian Stimulus

That is the title of a new and very good John Cochrane blog post on fiscal stimulus. Here is one excerpt from Cochrane:

New-Keynesian models act entirely through the real interest rate. Higher government spending means more inflation. More inflation reduces real interest rates when the nominal rate is stuck at zero, or when the Fed chooses not to respond with higher nominal rates. A higher real interest rate depresses consumption and output today relative to the future, when they are expected to return to trend. Making the economy deliberately more inefficient also raises inflation, lowers the real rate and stimulates output today. (Bill and Rong’s introduction gives a better explanation, recommended.)

So, the key proposition of new-Keynesian multipliers is that they work by increasing expected inflation. Bill and Rong look at that mechanism: did the ARRA stimulus in 2009 increase inflation or expected inflation? Their answer: No.

The paper itself is here.

Can persistent wage stickiness be the problem?

Stephen Williamson writes:

What about wage stickiness? That’s certainly important in the Keynesian narrative, though New Keynesians tend to think more about sticky prices. Suppose, for the sake of argument that a particular worker’s wage had been stuck at its pre-financial crisis nominal level until now. How much would that worker’s wage have declined in real terms by mid-2013? The answer depends on when the worker’s wage became stuck. If it was in January 2007, the decline would be 12% (using pce inflation); if in December 2007, 9%; and if when Lehman went down, 6%. That’s large in any case, and that’s with zero adjustment over 5 or 6 years. You think wage stickiness matters over that length of time, or that wage stickiness somehow explains the drop in employment we saw in the construction sector? I don’t think so.

Don’t forget that nominal gdp is now well above its pre-crash peak (some sticky wage theorists are morphing into “the stickiness is that almost everyone has to get a two percent raise each year,” a very different proposition than downward stickiness at the zero point and one with much less evidence behind it).

There are several other interesting observations in the piece. I don’t completely agree with this set of points (for one thing I don’t view TFP and investment as so readily separable), but they are nonetheless worth a ponder:

Probably the most important feature of the data in the two charts is the difference in the behavior of investment. In 1981-82, investment declines by about 12% from the first observation, then rebounds significantly, to the extent that it grew more than consumption and output by mid-1983. In the last recession, investment declined by more than 30% from the beginning of 2007 to mid-2009, and in second quarter 2013 was still about 5% lower than in first quarter 2007. Thus, if there is something we should be focusing on, it’s not multipliers and consumption, but why investment is so low. That low level of investment, over a five year period, has now had a significant cumulative effect on the capital stock. Thus, we’ve got OK growth in TFP, but growth in factor inputs is low. That’s the key story, from a growth accounting point of view.

You should not, by the way, think I have changed my mind on monetary policy. The “nominalist” approach was absolutely correct for 2008-2009, it is simply becoming less correct as time passes, which is exactly what standard economic theory suggests.

Guillermo Calvo on Austrian business cycle theory

Don’t worry too much about the failings of the Austrian economists themselves, rather focus on what we can learn from them. That is the tack taken by Guillermo Calvo in a recent paper (pdf), here is one excerpt:

I will argue that the Austrian School offered valuable insights – disregarded by mainstream macro theory…Over‐extension of credit was at center stage of the Austrian School theory of the trade (or business) cycle, but authors differed as to the factors responsible for excessive credit expansion. Mises (1952), for instance, attributed excessive expansion to central banks’ propensity to keeping interest rates low in order to ensure full employment at all times. As inflation flared up, interest rates were raised causing recession. Thus, under his view the cycle is triggered by pro-cyclical monetary policy with a full-employment bias which was not consistent with inflation stability. Hayek (2008), on the other hand, dismissed von Mises explanation, not because it was not a good depiction of historical events, but because he thought that instability is something inherent to the capital market and, in particular, it is related to what might be called the banking money multiplier mirage. His discussion conjures up contemporary issues, like securitized banking, for example. At the risk of oversimplifying, Hayek’s views, a phenomenon that seems central to his trade cycle theory is that credit expansion by bank A induces deposit expansion in bank B who, in turn, has incentives to further expand credit flows, etc. If bank A makes a mistake, the money-multiplier mechanism amplifies it. This is reminiscent of misperception phenomena stressed in Lucas (1972). Hayek’s discussion does not exhibit the same degree of mathematical sophistication but focuses on a richer set of highly relevant issues. For example, that credit expansion is not likely to be evenly spread across the economy, partly because of imperfect information or principal-agent problems. This implies that credit expansion is likely to have effects on relative prices which are not justified by fundamentals. Shocks that impinge on relative prices are hardly discussed in mainstream close-economy macro models. Hayek’s theory is very subtle and shows that even a central bank that follows a stable monetary policy may not be able to prevent business cycles and, occasionally, major boom-bust episodes. Unfortunately, Hayek does not quantity the impact of perception errors…

That is a bit long-winded, so here is how I would express some related points:

1. Once you cut through the free market (or anti-market rhetoric), the Austrian theory is not as different from Minsky’s as it sounds at first. And both sides hate it when you say this.

2. There may be a fundamental impossibility in maintaining orderly credit relations over time and the more sophisticated versions of the Austrian theory get at this. Keynes thought that too, but arguably “the liquidity premium of money itself” is a red herring when trying to understand this issue. In that sense Keynes may have been a step backwards.

3. The Austrian theory may require a rather “brute” behavioral imperfection concerning naive short-run overreactions to market prices, quantities, and flows. For reform economies, newly developing economies, and economies coming off a “great moderation,” this postulate may not be entirely unreasonable.

4. That credit booms precede many important busts, and play a causal role in those busts, and shape the nature of those busts, is a deeper point than Keynes let on in the General Theory.

5. One should never use the Austrian theory to dismiss the relevance of other, complementary approaches, most of all those which stress the dangers of deflationary pressures.

6. I don’t exactly agree with Calvo’s Mises vs. Hayek framing as stated.

The paper is interesting throughout and also offers a good discussion of Mexico’s peso crisis, and the point that, while allowing a deflationary contraction is a big mistake, simply trying to reflate won’t set matters right very quickly because there are real, non-monetary problems already baked into the contraction.

The original pointer is from Peter Boettke, who discusses the piece as well.