Results for “zmp” 73 found

Marcia Angell’s Mistaken View of Pharmaceutical Innovation

At Econ Talk, Marcia Angell discusses big Pharma with Russ Roberts. I think she gets a lot wrong. Here is one exchange on innovation.

Angell: The question of innovation–you said that some people feel, economists feel, [the FDA] slows up innovation: The drug companies do almost no innovation nowadays. Since the Bayh-Dole Act was enacted in 1980 they don’t have to do any innovation….

Roberts: But let’s just get a couple of facts on the table…[The] research and development budget of the pharmaceutical industry is, in 2009, was about $70 billion. That’s a very large sum of money. Are you suggesting that they don’t do anything–that that’s mostly or all marketing? That they are not trying to discover new applications of the basic research? It seems to me basic research is an important part. Putting that research into a form that can make us healthier seems to be a nontrivial thing. You think they are–what are they doing with that money?

Angell: If you look at the budgets of the major drug companies–just go to their annual reports, their Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, you see that Research and Development (R&D) is really the smallest part of their budget. If you look at the big companies you can divide their budget into 4 big categories. One is R&D, one is marketing and administration; the other is profits, and the other is just the cost of making the pills and putting them in the bottles and distributing them. The smallest of those is R&D.

Notice that Angell first claims the pharmaceutical companies do almost no innovation then, when presented with a figure of $70 billion spent on R&D, she switches to an entirely different and irrelevant claim, namely that spending on marketing is even larger. Apple spends more on marketing than on R&D but this doesn’t make Apple any less innovative. Angell’s idea of splitting up company spending into a “budget” is also deeply confused. The budget metaphor suggests firms choose among R&D, marketing, profits and manufacturing costs just like a household chooses between fine dining or cable TV. In fact, if the marketing budget were cut, revenues would fall. Marketing drives sales and (expected) sales drives R&D. Angell is like the financial expert who recommends that a family save money by selling its car forgetting that without a car it makes it much harder to get to work.

Later Angell tries a third claim namely that pharma companies do no innovation because their R&D budget is mostly spent on clinical trials and, “it’s no secret how to do a clinical trial.” I find this line of reasoning bizarre. I define an innovation as the novel creation of value, in this case the novel creation of valuable knowledge. Is Angell claiming that clinical trials do not provide novel and valuable knowledge? (FYI, I have argued that the FDA is overly safety conscious and requires too many trials but Angell breezily and nastily dismisses this argument). In point of fact, most new chemical entities die in clinical trial because what we thought would work in theory doesn’t work in practice. Moreover, the information generated in the clinical trials feeds back into basic research. Angell’s understanding of innovation is cramped and limited, she thinks it begins and ends with basic science in a university lab. Edison was right, however, when he said that genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration–both parts are required and there is no one-way line of causation, perspiration can lead to inspiration as well as vice-versa. Read Derek Lowe on the reality of the drug discovery process.

Angell infuses normative claims to the industrial organization of the pharmaceutical industry. Over the past two decades there has been an increase in the number of small biotechnology companies, often funded by venture capital. Most of the small biotechs are failures, they never produce a new molecular entity (NME). But a large number of small, diverse, entrepreneurial firms can explore a big space and individual failure has been good for the small-firm industry which collectively has increased its discovery of NMEs. The small biotechs, however, are not well placed to deal with the FDA and run large clinical trials–the same is also true of university labs. So the industry as a whole is evolving towards a network model in which the smaller firms explore a wide space of targets and those that hit gold partner with one of the larger firms to pursue development. Angell focuses in on one part of the system, the larger firms and denounces them for not being innovative. Innovation, however, should be ascribed not to any single node but to the network, to the system as a whole.

Angell makes some good points about publication bias in clinical trials and the sometimes too-close-for-comfort connections between the FDA, pharmaceutical firms, and researchers. But in making these points she misses the truly important picture. Namely that new pharmaceuticals have driven increases in life expectancy but pharmaceutical productivity is declining as the costs of discovering and bringing a new drug to market are rising rapidly (on average ~1.8 billion per each NME to reach market). In my view, the network model pursued on a global scale and a more flexible and responsive FDA, both of which Angell castigates, are among the best prospects for an increase in pharmaceutical productivity and thus for increases in future life expectancy. Nevertheless, whatever the solutions are, we need to focus on the big problem of productivity if we are to translate scientific breakthroughs into improvements in human welfare.

Assorted links

Assorted links

1. Anders Alsund on the Baltics, and growing economic troubles in Slovenia.

2. Can we (should we?) “cognitively enhance” monkeys? Is that even what we are doing? The paper itself is here.

3. Charles Murray on early intervention, see also the broader symposium.

4. Costs of bankruptcy illiquid collateral horse nationalism, and these are not ZMP goats.

Internet Killed the Porn Star

Free porn is killing the professional industry reports Louis Theroux in the Guardian.

Fees for scenes, not surprisingly, have taken a hit. “Some girls get $600 [£390] for a scene now,” the retired performer JJ Michaels tells me. “It might be $900-$1,000 for a big-name girl. It used to get up to $3,000.” For guys, rates can be $150 or lower [25 cents for every dollar a woman earns, AT]

Musicians have adjusted to declining music sales by increasing the number of live shows and porn stars are doing something similar:

It’s an open secret in the porn world that many female performers are supplementing their income by “hooking on the side”…For many female performers nowadays, the movies are merely a sideline, a kind of advertising for their real business of prostitution.

Many porn stars are now ZMP workers says Theroux:

“The way it is now, within five years I don’t see how there could be a professional porn actor,” Michaels tells me. It’s not easy to sympathise with the porn companies, which made so much money for so long by embracing a tawdry business and a dysfunctional work-pool. But it is worth sparing a thought for the legions of performers, qualified for nothing much more than having sex on camera, who have no money saved, and no future.

A pay what you want model worked for Radiohead but will probably not work for porn:

…it is difficult to see how a business selling hardcore movies and even internet clips is sustainable when most people simply don’t want to pay if they don’t have to. To many people, when it comes to porn, not paying for content seems the more moral thing to do.

Assorted links

Why is unemployment so high in South Africa?

Ryan Cooper writes to me:

Hey Tyler, possible blog post topic: I’m wondering how you would explain the situation in South Africa (or other similar countries) with stupendous persistent unemployment–SA has been above 20% since 2000: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-rate

A few factors I imagine are important:

1) The education system is totally broken in a lot of places. As in, 12th graders can neither read nor write in any language nor figure out 3×3 in their heads.

2) Unions are crazy strong, and have been driving up wages like gangbusters, particularly in the public sector.

3) Minimum wage laws are stringent and have actually led to worker protests: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/27/world/africa/27safrica.html?pagewanted=all

4) Inflation hasn’t been TOO bad recently (~6%), but has seen spikes to almost 14 percent not long ago: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/inflation-cpi

5) There’s a highly developed sector. On average, whites are far richer than blacks.6) Crime and inequality are incredibly bad.

7) The ANC has won every election in a landslide and is strongly allied with the unions.So how does it tie together? Lots of poorly-educated ZMP layabouts? Wages too high to start sweatshop-style development? Razor wire + electric fence + security guard costs deterring investment? The results of generations of systematic oppression and denial of education? All of the above, plus some?

Just trying to iron out a coherent story. I was a Peace Corps volunteer for two years there and I’m slowly building up my economics knowledge; this question has always fascinated me.

Assorted links

Questions that are rarely asked

From Arnold Kling (and the graph is from Karl Smith):

I challenge any supporter of the sticky-wage story (Bryan? Scott?) to write a 500-word essay explaining how this graph does not contradict their view. If employment fluctuations consisted of movements along an aggregate labor demand schedule, then employment should be at an all-time high right now.

My view is “sticky nominal wages for some, negative AD shock, ongoing stagnation and thus low job creation, and the progress we have is in some sectors immense but typically labor-saving rather than job-creating, all topped off with a liquidity shock-induced revelation that two percent of the previous work force was ZMP.” (Try screaming that from the rooftops.) I read the above graph as consistent with that mixed and moderate view. As Arnold notes, it’s harder to square with an AD-only view. If I wanted to push back a bit on Arnold’s take, and save some room for AD stories, I would cite the “Apple Fact of the Day,” and also note that stock prices have not responded nearly as well as have measured corporate profits. Still, we economists are not taking this graph seriously enough.

Addendum: Arnold Kling responds to responses.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit

The skills necessary to ride a bike are multifaceted, complex and not at all obvious or even easily explicable to the conscious mind. Once you learn, however, you never forget–that is the power of habit. Without the power of habit, we would be lost. Once a routine is programmed into system one (to use Kahneman’s terminology) we can accomplish great skills with astonishing ease. Our conscious mind, our system two, is not nearly fast enough or accurate enough to handle even what seems like a relatively simple task such as hitting a golf ball–which is why sports stars must learn to turn off system two, to practice “the art of not thinking,” in order to succeed.

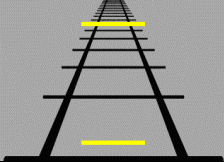

Habits, however, can easily lead one into error. In the picture at right, which yellow line is longer? System one tells us that the l ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

You never forget how to ride a bike. You also never forget how to eat, drink, or gamble–that is, you never forget the cues and rewards that boot up your behavioral routine, the habit loop. The habit loop is great when we need to reverse out of the driveway in the morning; cue the routine and let the zombie-within take over–we don’t even have to think about it–and we are out of the driveway in a flash. It’s not so great when we don’t want to eat the cookie on the counter–the cookie is seen, the routine is cued and the zombie-within gobbles it up–we don’t even have to think about it–oh sure, sometimes system two protests but heh what’s one cookie? And who is to say, maybe the line at the top is longer, it sure looks that way. Yum.

System two is at a distinct disadvantage and never more so when system one is backed by billions of dollars in advertising and research designed to encourage system one and armor it against the competition, skeptical system two. Yes, a company can make money selling rope to system two, but system one is the big spender.

Habits can never truly be broken but if one can recognize the cues and substitute different rewards to produce new routines, bad habits can be replaced with other, hopefully better habits. It’s habits all the way down but we have some choice about which habits bear the ego.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit, about which I am riffing off here, is all about habits and how they play out in the lives of people, organizations and cultures. I most enjoyed the opening and closing sections on the psychology of habits which can be read as a kind of user’s manual for managing your system one. The Power of Habit, following the Gladwellian style, also includes sections on the habits of corporations and groups (hello lucrative speaking gigs) some of these lost the main theme for me but the stories about Alcoa, Starbucks and the Civil Rights movement were still very good.

Duhigg is an excellent writer (he is the co-author of the recent investigative article on Apple, manufacturing and China that received so much attention) It will also not have escaped the reader’s attention that if a book about habits isn’t a great read then the author doesn’t know his material. Duhigg knows his material. The Power of Habit was hard to put down.

Is Jeremy Lin a fluke?

Nate Silver says no. I say that in Mike D’Antoni’s offensive schemes a lot of point guards reap more than the statistics they would pick up on other teams and from other offenses, and since the D’Antoni scheme is not very generalizable, or capable of winning a championship, the “other team” metrics are more or less the correct ones. Who else thinks the Knicks can continue to steamroll through victories like this, with or without their two “stars”? (ZMPers I call them.) I say he’s been toasting a number of teams that don’t have real defense against good attacking point guards, such as Washington and the Lakers. I think he will be very good but maybe someone like Fat Lever or Kenny Smith is the right comparison. That’s stillgood. In the playoffs, with a real defender on him, I suspect he is just another good player. He was by the way an economic major at Harvard, let’s ask Mankiw.

Addendum: Via Ben Casnocha, here is Metta to Lin.

The Innovation Nation versus the Warfare-Welfare State

We like to think of ourselves as an innovation nation but our government is a warfare-welfare state. To build an economy for the 21st century we need to increase the rate of innovation and to do that we need to put innovation at the center of our national vision. Innovation, however, is not a priority of our massive federal government.

Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. federal budget, $2.2 trillion annually, is spent on just the four biggest warfare and welfare programs, Medicaid, Medicare, Defense and Social Security. In contrast the National Institutes of Health, which funds medical research, spends $31 billion annually, and the National Science Foundation spends just $7 billion.

That’s me writing at The Atlantic drawing on Launching the Innovation Renaissance. Here is one more bit:

Our ancestors were bold and industrious–they built a significant portion of our energy and road infrastructure more than half a century ago. It would be almost impossible to build that system today. Could we build the Hoover Dam today? We have the technology but do we have the will? Unfortunately, we cannot rely on the infrastructure of our past to travel to our future. Airports, an electricity smart grid that doesn’t throw millions into the dark every few years, ubiquitous Wi-Fi — these are among the important infrastructures of the 21st century, and they are caught in the regulatory thicket.

Putting innovation at the center of the national vision is not simply about spending more, it’s about how we approach all problems. Read the whole thing for more discussion of regulation and other issues.

Why is Swiss unemployment so low?

Why does Switzerland have a low unemployment rate?

…is a question from Really Curious. Here are some data, but right now it is at 3.1%. I see a few factors:

1. The Swiss have few ZMPers, so their natural rate is fairly low to begin with.

2. The Swiss do not have the same kind of welfare state and labor legislation that you find say in France, which also lowers their natural rate, and which makes adjustment to negative shocks easier. Unemployment benefits are not so generous and they pretty much force you to try to find work again.

3. In the past the Swiss have managed their immigration policy in accord with the domestic unemployment rate. For instance if unemployment was rising they would send some Italian guest workers back home. Immigration into Switzerland is now so substantial, however, and integrated into so many sectors, that this procedure has lost its potency.

4. Swiss jobs are relatively permanent, compared to the United States. You will note that #4 interacts with #3; immigration is by no means always or even usually zero-sum with respect to the jobs in a country, but it can be for some well-defined pockets of manufacturing jobs in Switzerland.

5. The Swiss central bank does not hesitate to engage in sophisticated schemes of quantitative easing when an appreciating exchange rate is squeezing their export industries or they otherwise face unpleasant macroeconomic situations.

Here is a JSTOR piece on said question. Here is a good paper on the overall topic (pdf). I have never seen a good paper on why the Swiss unemployment rate rose somewhat in the early 1990s, falling again in 1996 or so I believe, but MR readers can help us out here. I also do not have knowledge of exactly how the Swiss calculate their unemployment rate, though it is unlikely that the difference in rates is a mere statistical artifact.

Assorted links

1. ZMP donkeys.

2. They should put all that energy into choosing a better restaurant.

3. Getting drunks to buy your stuff.

4. Paul Sweezy on stagnation, circa 1982.

5. The culture that is America, Univision edition.

Assorted links

1. Excellent fictional saga of a ZMP worker.

2. Model this, I call it the best and deepest game of hockey ever. Seriously.

3. Smallest frogs, tinier than a penny, newly discovered.

Assorted links

1. How the sellers of wedding dresses limit arbitrage, and is the Target 2 debate all screwed up?

2. How to reemploy some ZMPers (an epistolary romance), and British royalty adopt ZMP Greek donkeys.

3. No one has a good theory of collateral.

4. Markets in everything, at two different levels, British royalty edition, via Bob Cottrell.

5. Blog with Perry Mehrling and others.

6. What the Khan Academy is really up to, namely measuring when learning occurs or not.