Results for “FDA” 465 found

FDA Device Regulation

In the interests of length I had to sacrifice a few points in my WSJ review of Innovation Breakdown by Joseph Gulfo (excerpted on MR yesterday). In the review, I argued that the FDA could speed the approval of medical devices and reduce uncertainty by not reviewing directly but becoming a certifier of certifiers as is done in Europe.

In fact, a US model is already in place. OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health, requires that a range of electrical products and materials meet certain safety standards but it outsources certification to Underwriters Laboratories and other Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratories. We could and should do the same for medical devices and for drugs. Indeed, if a device or drug is permitted in a developed, advanced economy such as in Europe, Australia and Japan then I see no reason why it ought not to be provisionally approved in the United States (and vice-versa).

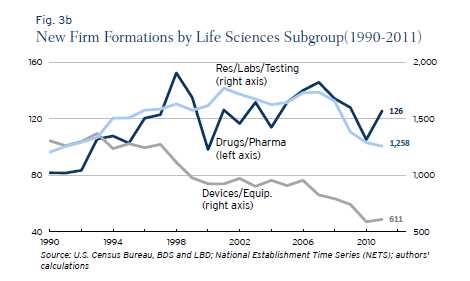

My paper with DiMasi and Milne showed that some FDA drug divisions appear to be much more productive than other divisions suggesting possibilities for substantial improvements if best practices were uniformly adopted. There also appear to be substantial differences between the regulation of drugs and devices especially in recent years. Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan have a new paper on Entrepreneurship and Job Creation in the U.S. Life Sciences Sector that shows that new firm creation in the medical device sector has fallen drastically since 1990 and far more than in the drug sector. Although there are likely many causes, the drop in the number of new firms is consistent with Gulfo’s experience of regulatory uncertainty and may suggest increases in regulatory cost for devices relative to drugs. Here is Hathaway and Litan:

The medical devices and equipment sector, on the other hand, saw new firm formations decline steadily and persistently between 1990 and 2011—falling by 695 firms or 53 percent during that period. Its share of new life sciences firms fell to 31 percent in 2011 from 50 percent in 1990. Unlike its life sciences sector counterparts, the decline in new firm formations in this segment appears to stretch beyond the cyclical effects of the Great Recession.

Ebola and the FDA

The Telegraph reports:

The two American doctors who have caught Ebola have been treated with a new “secret serum” which could potentially save their lives.

…A source close to the Atlanta hospital, where Dr Brantly is being treated, told CNN: “Within an hour of receiving the medication, Brantly’s condition was nearly reversed. His breathing improved; the rash over his trunk faded away.”

One of his doctors reportedly described the events as “miraculous.”

…Dr Writebol was also administrated with the drug, which was transported to Liberia in a special sub-zero container. She showed a less remarkable recovery, but is hoped to travel to the US on Tuesday to continue her treatment.

According to CNN, the drug was developed by the biotech firm Mapp Biopharmaceutical, based in California. The patients were told that this treatment had never been tried before in a human being but had shown promise in small experiments with monkeys.

…health workers said drugs that could fight Ebola are not particularly complicated but pharmaceutical firms see no economic reason to invest in making them because the virus’ few victims are poor Africans.

Of course, pharmaceutical firms are not going to invest millions in getting a drug through FDA trials for a disease that has only killed a few thousand people since being discovered in 1976. Nevertheless, some people find this simple logic difficult to accept.

Prof John Ashton, Britain’s leading public health doctor, termed the “moral bankruptcy” of profit-driven drugs developers.

The logic of profit-driven drug developers is no different than the logic of profit driving automobile manufactures. It isn’t profitable to make cars for people who can’t afford them but the auto firms are rarely called morally bankrupt for not giving cars away to the poor. Moreover, it’s not at all obvious why the burden of producing unprofitable drugs should fall on the drug manufacturers. To the extent that there is an ethical case for developing drugs for the poor it’s a burden that falls on all of us.

As Eric Crampton notes there are at least two possible solutions. Either ensure at taxpayer expense a return on investment by subsidizing, offering prizes (as I suggested in Launching) or publicly investing in orphan drugs or

…ease up the FDA trials for drugs in this kind of category. Does it really make sense to mandate placebo trials for drugs hitting diseases with 60% fatality rates? We are condemning people to a very high risk of death for the sake of ensuring that there aren’t drug side effects and that the drugs are more effective than placebos (pretty easy to tell quickly where the fatality rate is otherwise 60%!).

Rating the FDA by Division: Comparison with EMA

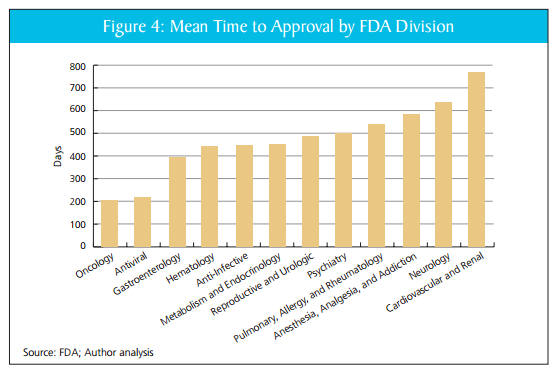

Reporters have been asking the FDA about my paper with DiMasi and Milne, AN FDA REPORT CARD. As you may recall, the upshot of that paper is that there is wide variance in the performance of FDA divisions. Here, for example, is the mean time to approval across divisions.

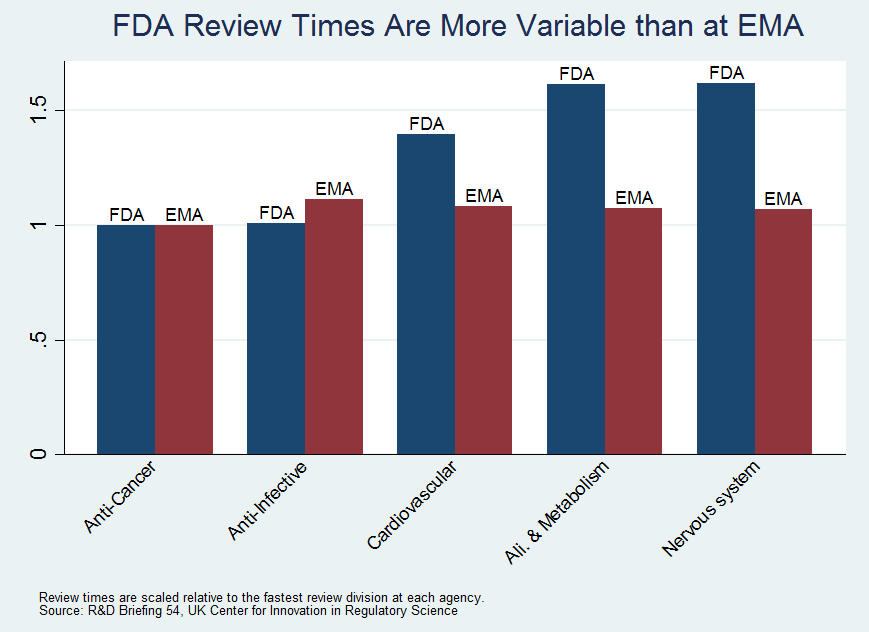

Our simple index, discussed in the paper, suggests that these differences are not easily explained by factors such as resources, complexity of task or differences in safety tradeoffs across divisions. In responding to our paper, however, the FDA has said that similar differences in time to approval by drug type are seen at other drug approval agencies. If true, that would be an important criticism.

Fortuitously, some relevant data crossed our desk recently. The Center for Innovation in Regulatory Science (CIRS), a UK based research consortium, compared median review times at the FDA to the next most important drug regulatory agency in the world, the European Medicines Agency (they also look at the Japanese agency). To their credit, the FDA is faster on average than the EMA (thanks PDUFA!). What is relevant for our purposes, however, is to compare differences across divisions.

The CIRS breaks drugs into broader classes than we used but the story they tell for the FDA is similar to ours; anti-cancer drugs, for example, are approved much more quickly than neurology drugs. The story for the EMA, however, is very different than for the FDA. For the EMA all types of drugs are approved in roughly the same amount of time.

We have argued that the wide variance in performance at the FDA is suggestive of differences in productivity. The fact that we do not see the same wide variance in performance at the EMA is supportive of our argument. Our goal and conclusion still stand:

We support further study to identify the policies and procedures that are working in high-performing divisions, with the goal of finding ways to apply them in low-performing divisions, thereby improving review speed and efficiency.

Rating the FDA by Division

In previous work, I have argued that asymmetric incentives make the FDA too risk averse with the result being excessive drug lag and drug loss. The FDA, however, is not a monolithic agency, it is divided into divisions which oversee different types of drugs. The divisions have different cultures, expectations histories and understandings. In my latest paper, written with Tufts researchers Joe DiMasi and Chris Milne, we put aside the question of global efficiency and ask a different question. How do the FDA divisions rate against one another? What we find is quite surprising: some of the FDA divisions appear to be much more productive than others. From the abstract:

After reviewing nearly 200 products accounting for 80 percent of new drug and biologic launches from 2004 to 2012, the authors find wide variation in division performance. In fact, the most productive divisions (Oncology and Antivirals) approve new drugs roughly twice as fast as the CDER average and three times faster than the least efficient divisions—without the benefit of greater resources, reduced complexity of task, or reduction in safety. The authors estimate that a modest narrowing of the CDER divisional productivity gap would reduce drug costs by nearly $900 million annually. The worth to patients, however, would be far greater if the agency could accelerate access to an additional generation of (about 25) drugs. Greater agency efficiency would be worth about $4 trillion in value to patients, from enhanced U.S. life expectancy. To reap such gains, this study encourages Congress and the FDA to more closely evaluate the agency’s most efficient drug review divisions, and apply the lessons learned across CDER. We also propose a number of reforms that the FDA and Congress should consider to improve efficiency, transparency, and consistency at the divisional level.

Andrew von Eschenbach a former Commissioner of the FDA and Director of the National Cancer Institute and now chairman of the Manhattan Institute’s Project FDA wrote a foreword to our paper. Eschenbach writes:

The authors of this report have taken a giant step…by assembling and analyzing a wide array of publicly available information about the relative performance of individual CDER divisions….Continuous, quality improvement measures routinely used by private industry could serve FDA leadership, sponsors, and patients by discerning factors that contribute to an optimal level of performance and, more important, disseminating such practices to ensure that all divisions achieve that performance. The payoff for such an effort could be enormous.

…Process improvement should not be a controversial proposal. An organization like the FDA—which is over a century old and which has maintained its current, basic organizational framework for decades—requires new tools to adapt to changing circumstances.

…I have enjoyed no greater privilege in my professional career than serving alongside the FDA’s talented staff. Today, the agency has more potential than ever to help the U.S. lead the world in advancing a biomedical revolution, one that will have an impact on every aspect of America’s economy and health-care system by improving health, increasing productivity, and reducing overall health-care costs.

…this report should be viewed as a positive, constructive contribution to a desperately needed dialogue on how to assist the agency in fulfilling this vital national goal.

Still Burned by the FDA

Excellent piece in the Washington Post on the FDA and sunscreen:

…American beachgoers will have to make do with sunscreens that dermatologists and cancer-research groups say are less effective and have changed little over the past decade.

That’s because applications for the newer sunscreen ingredients have languished for years in the bureaucracy of the Food and Drug Administration, which must approve the products before they reach consumers.

…The agency has not expanded its list of approved sunscreen ingredients since 1999. Eight ingredient applications are pending, some dating to 2003. Many of the ingredients are designed to provide broader protection from certain types of UV rays and were approved years ago in Europe, Asia, South America and elsewhere.

If you want to understand how dysfunctional regulation has become ponder this sentence:

“This is a very intractable problem. I think, if possible, we are more frustrated than the manufacturers and you all are about this situation,”

Who said it? Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research! Or how about this:

Eleven months ago, in a hearing on Capitol Hill, FDA Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg told lawmakers that sorting out the sunscreen issue was “one of the highest priorities.”

If this is high priority what happens to all the “low priority” drugs and medical devices?

The whole piece in the Washington Post is very good, read it all. I first wrote about this issue last year.

Addendum: See FDAReview.org for more on the FDA regulatory process and its reform.

The other hand of the FDA

Via Chaim Katz, here is a Bloomberg headline from 2012: “Asian Seafood Raised on Pig Feces Approved for U.S. Consumers.” Whether or not you agree with this decision (how good is disclosure?), you get the point.

The FDA and International Reciprocity

Bacterial meningitis causes swelling of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. In the United States the disease kills approximately 500 people a year, often within days of infection. Survivors can have permanent disabilities including paralysis and mental disabilities. Since March seven cases of the type B strain have been diagnosed at Princeton University, with one case just last week. A vaccine exists and is available in Europe and Australia but the FDA has not permitted the type B vaccine for use in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, has lobbied the FDA and they have now received special and unusual permission to import the type B vaccine. Following the CDCs recommendation, Princeton University has agreed to administer and pay for the vaccine for any student that wants it.

It’s good that the FDA has lifted the ban on the type B vaccine but why should Americans have to wait for the FDA? Americans living in Europe or Australia can be prescribed the vaccine so why not here? I believe that Americans should have the right to be prescribed any drug that has been approved in Europe, Australia, Canada, Japan or other developed nation.

Indeed, as Dan Klein and I wrote at FDAReview.org, international reciprocity of drug approvals is simple common sense:

If the United States and, say, Great Britain had drug-approval reciprocity, then drugs approved in Britain would gain immediate approval in the United States, and drugs approved in the United States would gain immediate approval in Great Britain. Some countries such as Australia and New Zealand already take into account U.S. approvals when making their own approval decisions. The U.S. government should establish reciprocity with countries that have a proven record of approving safe drugs—including most west European countries, Canada, Japan, and Australia. Such an arrangement would reduce delay and eliminate duplication and wasted resources. By relieving itself of having to review drugs already approved in partner countries, the FDA could review and investigate NDAs more quickly and thoroughly.

As has now become clear, international reciprocity is not just about choice it can also save lives.

A New FDA for the Age of Personalized, Molecular Medicine

In a brilliant new paper (pdf) (html) Peter Huber draws upon molecular biology, network analysis and Bayesian statistics to make some very important recommendations about FDA policy. Consider the following drugs (my list):

Drug A helps half of those to whom it is prescribed but it causes very serious liver damage in the other half. Drug B works well at some times but when administered at other times it accelerates the disease. Drug C fails to show any effect when tested against a placebo but it does seem to work in practice when administered as part of a treatment regime.

Which of these drugs should be approved and which rejected? The answer is that all of them should be approved; that is, all of them should be approved if we can target each drug to the right patient at the right time and with the right combination of other drugs. Huber argues that Bayesian adaptive testing, with molecular biology and network analysis providing priors, can determine which patients should get which drugs when and in what combinations. But we can only develop the data to target drugs if the drugs are actually approved and available in the field. The current FDA testing regime, however, is not built for adaptive testing in the field.

The current regime was built during a time of pervasive ignorance when the best we could do was throw a drug and a placebo against a randomized population and then count noses. Randomized controlled trials are critical, of course, but in a world of limited resources they fail when confronted by the curse of dimensionality. Patients are heterogeneous and so are diseases. Each patient is a unique, dynamic system and at the molecular level diseases are heterogeneous even when symptoms are not. In just the last few years we have expanded breast cancer into first four and now ten different types of cancer and the subdivision is likely to continue as knowledge expands. Match heterogeneous patients against heterogeneous diseases and the result is a high dimension system that cannot be well navigated with expensive, randomized controlled trials. As a result, the FDA ends up throwing out many drugs that could do good:

Given what we now know about the biochemical complexity and diversity of the environments in which drugs operate, the unresolved question at the end of many failed clinical trials is whether it was the drug that failed or the FDA-approved script. It’s all too easy for a bad script to make a good drug look awful. The disease, as clinically defined, is, in fact, a cluster of many distinct diseases: a coalition of nine biochemical minorities, each with a slightly different form of the disease, vetoes the drug that would help the tenth. Or a biochemical majority vetoes the drug that would help a minority. Or the good drug or cocktail fails because the disease’s biochemistry changes quickly but at different rates in different patients, and to remain effective, treatments have to be changed in tandem; but the clinical trial is set to continue for some fixed period that doesn’t align with the dynamics of the disease in enough patients

Or side effects in a biochemical minority veto a drug or cocktail that works well for the majority. Some cocktail cures that we need may well be composed of drugs that can’t deliver any useful clinical effects until combined in complex ways. Getting that kind of medicine through today’s FDA would be, for all practical purposes, impossible.

The alternative to the FDA process is large collections of data on patient biomarkers, diseases and symptoms all evaluated on the fly by Bayesian engines that improve over time as more data is gathered. The problem is that the FDA is still locked in an old mindset when it refuses to permit any drugs that are not “safe and effective” despite the fact that these terms can only be defined for a large population by doing violence to heterogeneity. Safe and effective, moreover, makes sense only when physicians are assumed to be following simple, A to B, drug to disease, prescribing rules and not when they are targeting treatments based on deep, contextual knowledge that is continually evolving:

In a world with molecular medicine and mass heterogeneity the FDA’s role will change from the yes-no single rule that fits no one to being a certifier of biochemical pathways:

By allowing broader use of the drug by unblinded doctors, accelerated approval based on molecular or modest—and perhaps only temporary—clinical benefits launches the process that allows more doctors to work out the rest of the biomarker science and spurs the development of additional drugs. The FDA’s focus shifts from licensing drugs, one by one, to regulating a process that develops the integrated drug-patient science to arrive at complex, often multidrug, prescription protocols that can beat biochemically complex diseases.

…As others take charge of judging when it is in a patient’s best interest to start tinkering with his own molecular chemistry, the FDA will be left with a narrower task—one much more firmly grounded in solid science. So far as efficacy is concerned, the FDA will verify the drug’s ability to perform a specific biochemical task in various precisely defined molecular environments. It will evaluate drugs not as cures but as potential tools to be picked off the shelf and used carefully but flexibly, down at the molecular level, where the surgeon’s scalpels and sutures can’t reach.

In an important section, Huber notes that some of the biggest successes of the drug system in recent years occurred precisely because the standard FDA system was implicitly bypassed by orphan drug approval, accelerated approval and off-label prescribing (see also The Anomaly of Off-Label Prescribing).

But for these three major licensing loopholes, millions of people alive today would have died in the 1990s. Almost all the early HIV- and AIDS-related drugs—thalidomide among them—were designated as orphans. Most were rushed through the FDA under the accelerated-approval rule. Many were widely prescribed off-label. Oncology is the other field in which the orphanage, accelerated approval, and off-label prescription have already played a large role. Between 1992 and 2010, the rule accelerated patient access to 35 cancer drugs used in 47 new treatments. For the 26 that had completed conventional followup trials by the end of that period, the median acceleration time was almost four years.

Together, HIV and some cancers have also gone on to demonstrate what must replace the binary, yes/ no licensing calls and the preposterously out-of-date Washington-approved label in the realm of complex molecular medicine.

Huber’s paper has a foreword by Andrew C. von Eschenbach, former commissioner of the FDA, who concludes:

For precision medicine to flourish, Congress must explicitly empower the agency to embrace new tools, delegate other authorities to the NIH and/or patient-led organizations, and create a legal framework that protects companies from lawsuits to encourage the intensive data mining that will be required to evaluate medicines effectively in the postmarket setting. Last but not least, Congress will also have to create a mechanism for holding the agency accountable for producing the desired outcomes.

Burned by the FDA

If you lived in Great Britain or Germany and your physician prescribed a pharmaceutical, would you ask them, “has this pharmaceutical been approved by the U.S. FDA?” Probably not. At FDAReview.org Dan Klein and I argue that international reciprocity is a no-brainer:

If you lived in Great Britain or Germany and your physician prescribed a pharmaceutical, would you ask them, “has this pharmaceutical been approved by the U.S. FDA?” Probably not. At FDAReview.org Dan Klein and I argue that international reciprocity is a no-brainer:

If the United States and, say, Great Britain had drug-approval reciprocity, then drugs approved in Britain would gain immediate approval in the United States, and drugs approved in the United States would gain immediate approval in Great Britain. Some countries such as Australia and New Zealand already take into account U.S. approvals when making their own approval decisions. The U.S. government should establish reciprocity with countries that have a proven record of approving safe drugs—including most west European countries, Canada, Japan, and Australia. Such an arrangement would reduce delay and eliminate duplication and wasted resources. By relieving itself of having to review drugs already approved in partner countries, the FDA could review and investigate NDAs more quickly and thoroughly.

Unfortunately, even when they can, the US FDA does not take advantage of international knowledge as the WSJ notes in European Sunscreen Roadblock on U.S. Beaches:

Eight sunscreen ingredient applications have been pending before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for years—some for up to a decade—for products available in many overseas countries. The applications were filed through the federal TEA process (time and extent application), which allows the FDA to approve the ingredients if they have been used for at least five years abroad and have proved effective and safe.

…Henry Lim, chairman of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology, says multiple UVA filters still awaiting clearance in the U.S. have been used effectively outside the country for years.

“The U.S. is an island by itself on this one,” he said. “They’re available in Canada, available in Europe, available in Asia, available in Mexico, and available in South America.”

The sunscreens available in the U.S. are not without risk and in some ways, as the WSJ discusses, the European standards are stricter than the US standards so there really is no reason why sunscreens available in Europe and Canada should not also be available in the United States.

Hat tip: Kurt Busboom.

Addendum: 27 states have driver’s license reciprocity with Germany. Why not pharmaceutical reciprocity? With hat tip to whatsthat in the comments.

Drug Shortages Caused by the FDA

Shortages of drugs, especially generic injectables, continue to cause significant harm to patients. A new Congressional report offers the best account to date of the shortages and provides details confirming my earlier post. The story in essence is this:

Shortages of drugs, especially generic injectables, continue to cause significant harm to patients. A new Congressional report offers the best account to date of the shortages and provides details confirming my earlier post. The story in essence is this:

The FDA began to ramp up GMP rules and regulations under the new commissioner in 2010 and 2011 (see figure at left (N.B. this includes all warning letters not just GMP so it is just illustrative, AT added). In fact, the report indicates that FDA threats shut down some 30% of the manufacturing capacity at the big producers of generic injectables. The safety of these lines was not a large problem and could have been handled with a targeted approach but instead the FDA launched a sweep against all the major manufacturers at the same time. These problem have been exacerbated by a change in Medicare reimbursement rules and by the rise of GPOs (buying groups) which reduced the prices of generics. Thus, in response to the cut in capacity, firms have shifted production from less profitable generics to more profitable branded drugs, so we get shortages of generics rather than of branded drugs.

The FDA began to ramp up GMP rules and regulations under the new commissioner in 2010 and 2011 (see figure at left (N.B. this includes all warning letters not just GMP so it is just illustrative, AT added). In fact, the report indicates that FDA threats shut down some 30% of the manufacturing capacity at the big producers of generic injectables. The safety of these lines was not a large problem and could have been handled with a targeted approach but instead the FDA launched a sweep against all the major manufacturers at the same time. These problem have been exacerbated by a change in Medicare reimbursement rules and by the rise of GPOs (buying groups) which reduced the prices of generics. Thus, in response to the cut in capacity, firms have shifted production from less profitable generics to more profitable branded drugs, so we get shortages of generics rather than of branded drugs.

Add to these major factors a few unique events such as the FDA now requiring pre-1938 and pre-62 drugs to go through expensive clinical trials, the slowdown of ANDAs and crazy stuff such as DEA control over pharmaceutical manufacturing and you get very extensive shortages.

Toward a 21st-Century FDA?

In a WSJ op-ed, Andrew von Eschenbach, FDA commissioner from 2005 to 2009, is surprisingly candid about how the FDA is killing people.

When I was commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 2005 to 2009, I saw firsthand how regenerative medicine offered a cure for kidney and heart failure and other chronic conditions like diabetes. Researchers used stem cells to grow cells and tissues to replace failing organs, eliminating the need for expensive supportive treatments like dialysis and organ transplants.

But the beneficiaries were laboratory animals. Breakthroughs for humans were and still are a long way off. They have been stalled by regulatory uncertainty, because the FDA doesn’t have the scientific tools and resources to review complex innovations more expeditiously and pioneer regulatory pathways for state-of-the-art therapies that defy current agency conventions.

Ultimately, however, von Eschenbach blames not the FDA but Congress:

Congress has starved the agency of critical funding, limiting its scientists’ ability to keep up with peers in private industry and academia. The result is an agency in which science-based regulation often lags far behind scientific discovery.

Should we not, however, read the following ala Strauss?

The FDA isn’t obstructing progress because its employees are mean-spirited or foolish.

…For example, in August 2010, the FDA filed suit against a company called Regenerative Sciences. Three years earlier, the company had begun marketing a process it called Regenexx to repair damaged joints by injecting them with a patient’s own stem cells. The FDA alleged that the cells the firm used had been manipulated to the point that they should be regulated as drugs. A resulting court injunction halting use of the technique has cast a pall over the future of regenerative medicine.

A peculiar example of a patient-spirited and wise decision, no? And what are we to make of this?

FDA scientists I have encountered do care deeply about patients and want to say “yes” to safe and effective new therapies. Regulatory approval is the only bridge between miracles in the laboratory and lifesaving treatments. Yet until FDA reviewers can be scientifically confident of the benefits and risks of a new technology, their duty is to stop it—and stop it they will. (emphasis added).

von Eschenbach ends with what sounds like a threat or perhaps, as they say, it is a promise. Unless Congress funds the FDA at higher levels and lets it regulate itself:

…we had better get used to the agency saying no by calling “time out” or, worse, “game over” for American companies developing new, vital technologies like regenerative medicine.

Frankly, I do not want to “get used” to the FDA saying game over for American companies but nor do I trust Congress to solve this problem. Thus, von Eschenbach convinces me that if we do want new, vital technologies like regenerative medicine we need more fundamental reform.

Andy Grove on Reforming the FDA

In an important editorial in Science, Andy Grove, former Chief Executive Officer of Intel Corporation, advocates restricting the FDA to safety-only trials. Instead of FDA required efficacy trials patients would be tracked using a very large, open database.

The biomedical industry spends over $50 billion per year on research and development and produces some 20 new drugs….A breakthrough in regulation is needed to create a system that does more with fewer patients.

While safety-focused Phase I trials would continue under their [FDA] jurisdiction, establishing efficacy would no longer be under their purview. Once safety is proven, patients could access the medicine in question through qualified physicians. Patients’ responses to a drug would be stored in a database, along with their medical histories. Patient identity would be protected by biometric identifiers, and the database would be open to qualified medical researchers as a “commons.” The response of any patient or group of patients to a drug or treatment would be tracked and compared to those of others in the database who were treated in a different manner or not at all. These comparisons would provide insights into the factors that determine real-life efficacy: how individuals or subgroups respond to the drug. This would liberate drugs from the tyranny of the averages that characterize trial information today. The technology would facilitate such comparisons at incredible speeds and could quickly highlight negative results. As the patient population in the database grows and time passes, analysis of the data would also provide the information needed to conduct postmarketing studies and comparative effectiveness research.

Grove cites Boldin and Swamidass and especially Bartley Madden’s important book, Free to Choose Medicine, as inspiration for this proposal. By the way, I also recommend Madden’s book very highly (I am also proud to note my bias in this regard).

I have long advocated restricting the FDA to safety only trials (see, for example, FDAReview.org and my paper on off-label prescribing) and it seems that this idea, once considered outlandish, is now rapidly gathering advocates.

Addendum: Derek Lowe offers useful comments (see also Kevin Outterson below). One point that I think the critics miss is that nothing in Groves’s proposal and certainly not in Madden’s proposal which is somewhat different or in anything that I have advocated precludes randomized clinical trials for efficacy. Indeed, I strongly support such trials and have argued for greater funding so such trials can be done not by the pharmaceutical companies but by more objective third parties.

FDA: Moving to a Safety-Only System

It now costs about a billion dollars to develop a new drug which means that many potentially beneficial drugs are lost. Economist Michele Boldrin and physician S. Joushua Swamidass explain the problem and suggest a new approach:

Every drug approval requires a massive bet—so massive that only very large companies can afford it. Too many drugs become profitable only when the expected payoff is in the billions….in this high-stakes environment it is difficult to justify developing drugs for rare diseases. They simply do not make enough money to pay for their development….How many potentially good drugs are dropped in silence every year?

Finding treatments for rare disease should concern us all. And as we look closely at genetic signatures of important diseases, we find that each common disease is composed of several rare diseases that only appear the same on the outside.

Nowhere is this truer than with cancer. Every patient’s tumor is genetically unique. That means most cancer patients have in effect a rare disease that may benefit from a drug that works for only a small number of other patients.

…We can reduce the cost of the drug companies’ bet by returning the FDA to its earlier mission of ensuring safety and leaving proof of efficacy for post-approval studies and surveillance.

Harvard Neurologist Peter Lansbury made a similar argument several years ago:

There are also scientific reasons to replace Phase 3. The reasoning behind the Phase 3 requirement — that the average efficacy of a drug is relevant to an individual patient — flies in the face of what we now know about drug responsiveness. Very few drugs are effective in all individuals. In fact, most are not effective in large portions of the population, for reasons that we are just beginning to understand.

It’s much easier to get approval for drugs that are marginally effective in, say, half the population than drugs that are very effective in a small fraction of patients. This statistical barrier discourages the pharmaceutical industry from even beginning to attack diseases, such as Parkinson’s, that are likely to have several subtypes, each of which may respond to a different drug. These drugs are the underappreciated casualties of the Phase 3 requirement; they will never be developed because the risk of failure at Phase 3 is simply too great.

Boldrin and Swamidass offer another suggestion:

In exchange for this simplification, companies would sell medications at a regulated price equal to total economic cost until proven effective, after which the FDA would allow the medications to be sold at market prices. In this way, companies would face strong incentives to conduct or fund appropriate efficacy studies. A “progressive” approval system like this would give cures for rare diseases a fighting chance and substantially reduce the risks and cost of developing safe new drugs.

Instead of price regulations I have argued for more publicly paid for efficacy studies, to be produced by the NIH and other similar institutions. Third party efficacy studies would have the added benefit of being less subject to bias.

Importantly, we already have good information on what a safety-only system would look like: the off-label market. Drugs prescribed off-label have been through FDA required safety trials but not through FDA-approved efficacy trials for the prescribed use. The off-label market has its problems but it is vital to modern medicine because the cutting edge of treatment advances at a far faster rate than does the FDA (hence, a majority of cancer and AIDS prescriptions are often off-label, see my original study and this summary with Dan Klein). In the off-label market, firms are not allowed to advertise the off-label use which also gives them an incentive, above and beyond the sales and reputation incentives, to conduct further efficacy studies. A similar approach might be adopted in a safety-only system.

Addendum: Kevin Outterson at The Incidental Economist and Bill Gardner at Something Not Unlike Research offer useful comments.

How the FDA Impedes Innovation

Mike Mandel has a good piece, significantly published by the Progressive Policy Institute, on the FDA and innovation. MelaFind is a handheld computer vision system, database and expert system that helps dermatologists to identify which skin lesions should be biopsied for melanoma. The device works quite well but the FDA has deemed the device “not approvable” because (quoting Mandel):

- The device did not do better than the experienced dermatologists in the study (“the FDA review team does not believe this is a clinically significant difference between MelaFind and the examining dermatologist”)

- The device was tested on lesions identified by experienced dermatologists, not on the broader set of lesions that might be identified by “physicians less experienced than these dermatologists.”

- The device did not find every melanoma in the sample (“Since the device is not 100% sensitive, if use based on the device’s diagnostic performance reduces the number of biopsies taken, harm could ensue in the form of missed melanomas.”)

- The device was not demonstrated to make inexperienced physicians the equal of experienced dermatologists (“Currently, formal training is offered to physicians to become board certified dermatologist and thus be able to diagnose clinically atypical lesions. The FDA review team would have to compare this board certification training to that offered by the sponsor to those physicians operating MelaFind to determine if it is found adequate.”

Some of these complaints are legitimate, others not so much. But even if MelaFind is not perfect today nor appropriate in all circumstances it’s exactly the type of innovation that we should encourage. Devices such as MelaFind could not only improve medical care they can reduce costs and make good quality medical care more widely available in developing countries, for example, where experienced dermatologists are in short supply.

Most importantly, innovations get better over time. But if you impede the first generation the second generation may never come into existence and, as Mandel notes, no first-generation device could satisfy the FDA’s conditions. It’s like refusing to give the Wright Brothers a license to fly because their first airplane only flew for 59 seconds.

The signal that is being sent by the FDA impedes all medical innovation.

For more on the FDA see FDAReview.org.

Device Lag at the FDA

A new survey of the FDAs impact on medical technology innovation reports that the FDA is slow, inefficient and costly. The survey is from the Medical Device Manufacturers Association so take it with a grain of salt (but see below). What is most telling, however, is how manufacturers rate the FDA compared to its European counterpart(s).

Overall Experience: 75 percent of respondents rated their regulatory experience in the EU excellent or very good. Only 16 percent gave the same ratings to the FDA…

Respondents also cite specific concerns with the FDA process (not just a general complaint of slowness which could be efficient) such as:

…44 percent of participants indicated that part-way through the regulatory process they experienced untimely changes in key personnel, including the lead reviewer and/or branch chief responsible for the product’s evaluation.

As a result:

On average, the products represented in the survey were available to patients in the U.S. a full two years after they were available to patients in Europe (range = 3 to 70 months later).

In some cases, respondents said they initiated their regulatory processes within and outside the U.S. at the same time, but received clearance/approval in the U.S. much later. In anticipation of long, expensive FDA reviews, others said they decided to seek or obtain European approval first in an effort to generate sales overseas that could help fund their U.S. regulatory efforts.

The survey has a good discussion of potential biases. To those not familiar with the industry it might seem obvious that the MDMA would want to bash the FDA but my experience is that companies in the business don't like to complain. Indeed, the survey notes:

A number of companies indicated that they would not respond due to fear of retribution from the FDA (despite assurances we would maintain their confidentiality).

See FDAReview for more on the FDA. Hat tip: Mike Mandel.

Addendum: Loyal reader Josh Turnage has produced a video plea to the FDA on behalf of his mother to leave Avastin approved for breast cancer.