Results for “licensing” 122 found

Saturday assorted links

1. Scott Alexander defends Silicon Valley.

2. Paying young Brazilian women to play Overwatch with you.

3. Eric Rasmusen on game theory and North Korea (not my view but will stimulate thought).

5. Clearly, a talking prairie dog (NYT). Recommended, and they also have TFP.

6. MIE: high prices for some “antique” IKEA furniture.

7. Contrarian argument that occupational licensing actually increases supply.

Baptists *are* bootleggers, medical marijuana edition

Four of New York’s five medical marijuana companies have filed suit against the state Department of Health to stop it from licensing additional operators to take part in the tightly run state program. The companies argue that the expansion could tank the nascent industry and potentially harm thousands of patients who rely on medical marijuana to treat their ailments.

Here is the article, via Peter Metrinko.

Why is female labor force participation down?

There have been so many blog posts on male labor force participation, it is time to give women some additional coverage. So Kubota, a job market candidate at Princeton, has an excellent paper on this topic.

Child Care Costs and Stagnating Female Labor Force Participation in the US

The increasing trend of the female labor force participation rate in the United States stopped and turned to a decline in the late 1990s. This paper shows that structural changes in the child care market play a substantial role in influencing female labor force participation. I first provide new estimates of long-term measures of prices and hours of child care using the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Hourly expenditure on child care rose by 40% and hours of daycare used declined by 20%. Next, I build a life-cycle model of married couples that features a menu of child care options that captures important features of reality. The calibrated model predicts that the rise in child care costs leads to a 5% decline in total employment of females, holding all else constant. Finally, this paper provides two hypotheses and their supporting evidence about the causes of rising child care costs: (i) restrictive licensing to home-based child care providers, and (ii) the negative effect of expanded child care subsidies to lower income households on the incentives for those individuals to operate the home-based daycare.

I will be continuing my coverage of interesting job market papers, as more interesting ones come on line.

Addendum: Kevin Drum adds comment.

Monday assorted links

1. How did Shenzhen become China’s innovation capital?

2. Twenty people who turned piling logs into an art form.

3. More on Trump and the west coast Straussians.

4. How democracy treats education: support for spending falls sharply when people learn how much is being spent.

5. The wisdom of Malcolm Gladwell.

Ban the Box or Require the Box?

Ban the box policies forbid employers from asking about a criminal record on a job application. Ban the box policies don’t forbid employers from running criminal background checks they only forbid employers from asking about criminal history at the application/interview stage. The policies are supposed to give people with a criminal background a better shot at a job. Since blacks are more likely to have a criminal history than whites, the policies are supposed to especially increase black employment.

One potential problem with these laws is that employers may adjust their behavior in response. In particular, since blacks are more likely than whites to have a criminal history, a simple, even if imperfect, substitute for not interviewing people who have a criminal history is to not interview blacks. Employers can’t ask about race on a job application but black and white names are distinctive enough so that based on name alone, one can guess with a high probability of being correct whether an applicant is black or white. In an important and impressive new paper, Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr examine how employers respond to ban the box.

Agan and Starr sent out approximately 15,000 fake job applications to employers in New York and New Jersey. Otherwise identical applications were randomized across distinctively black and white (male) names. Half the applications were sent just before and another half sent just after ban the box policies took effect. Not all firms used the box even when legal so Agan and Starr use a powerful triple-difference strategy to estimate causal effects (the black-white difference in callback rates between stores that did and did not use the box before and after the law).

Agan and Starr sent out approximately 15,000 fake job applications to employers in New York and New Jersey. Otherwise identical applications were randomized across distinctively black and white (male) names. Half the applications were sent just before and another half sent just after ban the box policies took effect. Not all firms used the box even when legal so Agan and Starr use a powerful triple-difference strategy to estimate causal effects (the black-white difference in callback rates between stores that did and did not use the box before and after the law).

Agan and Starr find that banning the box significantly increases racial discrimination in callbacks.

One can see the basic story in the situation before ban the box went into effect. Employers who asked about criminal history used that information to eliminate some applicants and this necessarily affected blacks more since they are more likely to have a criminal history. But once the applicants with a criminal history were removed, “box” employers called back blacks and whites for interviews at equal rates. In other words, the box leveled the playing field for applicants without a criminal history.

Employers who didn’t use the box did something simpler but more nefarious–they offered blacks fewer callbacks compared to otherwise identical whites, regardless of criminal history. Together the results suggest that employers use distinctively black names to statistically discriminate.

When the box is banned it’s no longer possible to cheaply level the playing field so more employers begin to statistically discriminate by offering fewer callbacks to blacks. As a result, banning the box may benefit black men with criminal records but it comes at the expense of black men without records who, when the box is banned, no longer have an easy way of signaling that they don’t have a criminal record. Sadly, a policy that was intended to raise the employment prospects of black men ends up having the biggest positive effect on white men with a criminal record.

Agan and Starr suggest one possible innovation–blind employers to names. I think that is the wrong lesson to draw. Agan and Starr look at callbacks but what we really care about is jobs. You can blind employers to names in initial applications but employers learn about race eventually. Moreover, there are many other margins for employers to adjust. Employers, for example, could simply start increasing the number of employees they put through (post-interview) criminal background checks.

Policies like ban the box try to get people to do the “right thing” by blinding people to certain types of information. But blinded people tend to use other cues to achieve their interests and when those other cues are less informative that often makes things worse.

Rather than ban the box a plausibly better policy would be to require the box. Requiring all employers to ask about criminal history would tend to hurt anyone with a criminal record but it could also level racial differences among those without a criminal record. One can, of course, argue either side of that tradeoff and that is my point.

More generally, instead of blinding employers a better idea is to change real constraints. At the same time as governments are forcing employers to ban the box, for example, they are passing occupational licensing laws which often forbid employers from hiring workers with criminal records. Banning the box and simultaneously forbidding employers from hiring workers with criminal records illustrates the incoherence of public policy in an interest-group driven system.

Ban the box is another example of good intentions gone awry because the man of system tries to arrange people as if they were pieces on a chessboard, without understanding that:

…in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder. (Adam Smith, ToMS)

Addendum 1: The Agan and Starr paper has much more of interest. Agan and Starr, find, for example, evidence of discrimination going beyond that associated with statistical discrimination and crime. In particular, whites are more likely to be hired in white neighborhoods and blacks are more likely to be hired in black neighborhoods.

Addendum 2: Agan was my former student at GMU. Her undergraduate paper (!), Sex Offender Registries: Fear without Function?, was published in the Journal of Law and Economics.

Why isn’t there more telemedicine?

Austin Frakt tells us:

The biggest hurdle may be state medical boards. Idaho’s medical licensing board punished a doctor for prescribing an antibiotic over the phone, fining her $10,000 and forbidding her from providing telemedicine. State laws that restrict telemedicine — for instance, requiring that patients and doctors have established in-person relationships — have drawn lawsuits charging that they illegally restrict competition. Georgia’s state medical board requires a face-to-face encounter before telemedicine can be delivered, while Ohio’s does not.

A study by Julia Adler-Milstein, an assistant professor at the School of Information and the School of Public Health, University of Michigan, found that such state laws and medical board requirements influence the extent of telemedicine use by hospitals. While 70 percent or more hospitals in Maine, South Dakota, Arkansas and Alaska use telemedicine, only 13 percent in Utah and none in Rhode Island do, for instance.

In a passionate commentary on the establishment’s hesitancy to embrace telemedicine, David Asch, a University of Pennsylvania physician, pointed out that the inconvenience of face-to-face care limits its use, but arbitrarily and invisibly. The costs of waiting and travel time and those borne by rural populations with poor access to in-person care don’t appear on the books. “The innovation that telemedicine promises is not just doing the same thing remotely,” Dr. Asch wrote, “but awakening us to the many things that we thought required face-to-face contact but actually do not.”

Here is the full NYT account.

Declining Mobility and Restrictions on Land Use

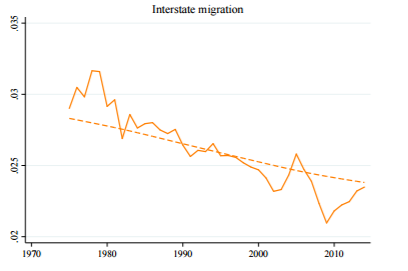

Mobility has been slowly falling in the United States since the 1980s. Why? One possibility is demographic changes. Older people, for example, are less likely to move than younger people so increases in the elderly population might explain declines in mobility. Mobility has declined, however, for people of all ages. In the 1980s, for example, 3.6% of people aged 25-44 had moved in the last year but in the 2000s only 2.2% of this age group had moved.

(Graph from Molloy, Smith, Trezzi and Wozniak).

(Graph from Molloy, Smith, Trezzi and Wozniak).In fact, mobility has declined within age, gender, race, home ownership status, whether your spouse works or not, income class, and employment status so whatever the cause of declining mobility it has to be big enough to affect large numbers of people across a range of demographics.

My best guess is that the decline in mobility is due to problems in our housing markets (I draw here on an important paper by Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag). It used to be that poor people moved to rich places. A janitor in New York, for example, used to earn more than a janitor in Alabama even after adjusting for housing costs. As a result, janitors moved from Alabama to New York, in the process raising their standard of living and reducing income inequality. Today, however, after taking into account housing costs, janitors in New York earn less than janitors in Alabama. As a result, poor people no longer move to rich places. Indeed, there is now a slight trend for poor people to move to poor places because even though wages are lower in poor places, housing prices are lower yet.

Ideally, we want labor and other resources to move from low productivity places to high productivity places–this dynamic reallocation of resources is one of the causes of rising productivity. But for low-skill workers the opposite is happening – housing prices are driving them from high productivity places to low productivity places. Furthermore, when low-skill workers end up in low-productivity places, wages are lower so there are fewer reasons to be employed and there aren’t high-wage jobs in the area so the incentives to increase human capital are dulled. The process of poverty becomes self-reinforcing.

Why has housing become so expensive in high-productivity places? It is true that there are geographic constraints (Manhattan isn’t getting any bigger) but zoning and other land use restrictions including historical and environmental “protection” are reducing the amount of land available for housing and how much building can be done on a given piece of land. As a result, in places with lots of restrictions on land use, increased demand for housing shows up mostly in house prices rather than in house quantities.

In the past, when a city like New York became more productive it attracted the poor and rich alike and as the poor moved in more housing was built and the wages and productivity of the poor increased and national inequality declined. Now, when a city like San Jose becomes more productive, people try to move to the city but housing doesn’t expand so the price of housing rises and only the highly skilled can live in the city. The end result is high-skilled people living in high-productivity cities and low-skilled people live in low-productivity cities. On a national level, land restrictions mean less mobility, lower national productivity and increased income and geographic inequality.

From my answer on Quora.

Here is my post on occupational licensing and declines in mobility.

The Logic of Closed Borders

Bloomberg: At least 100 workers at the construction site for Tesla Motors Inc.’s battery factory near Reno, Nevada, walked off the job Monday to protest use of workers from other states, a union official said.

Local labor leaders are upset that Tesla contractor Brycon Corp. is bringing in workers from Arizona and New Mexico, said Todd Koch, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Northern Nevada.

“It’s a slap in the face to Nevada workers to walk through the parking lot at the job site and see all these license plates from Arizona and New Mexico,” Koch said in an interview. Those who walked out were among the hundreds on the site, he said.

Erik Brynjolfsson tweeted “Build a wall! And make New Mexico pay for it.” Or perhaps require that Nevada carpenters be licensed.

The optimal regulation of massage and prostitution

The job market paper of Amanda Nguyen, of UCLA, is on that topic, I found her results intriguing:

Despite its illegality, prostitution is a multi-billion dollar industry in the U.S. A growing share of this black market operates covertly behind massage parlor fronts. This paper examines how changes to licensing in the legal market for massage parlors can impact the total size and risk composition of the black market for prostitution, which operates either illegally through escorts or quasi-legally in massage parlors. These changes in market structure and risk consequently determine the net impact of prostitution on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and sexual violence. I track the impact of two policy changes in California that resulted in large variation in barriers to entry via massage licensing fees. Using a novel dataset scraped from Internet review websites, I find that lower barriers to entry for massage parlors makes the black market for prostitution larger, but also less risky. This is due to illegal prostitution buyers and suppliers switching to the quasi-legal sector, as well as quasi-legal sex workers facing a reduced wage premium for high-risk behavior. Consequently, the incidence of gonorrhea and rape falls in the general population. I also present evidence that growth in the quasi-legal sector imposes a negative competition externality on purely legal massage firms.

I don’t find the rape result intuitive, but I am seeing it pop up in a number of papers, so perhaps it should be taken seriously.

Wednesday assorted links

2. Brink Lindsey: Low-hanging fruit guarded by dragons.

3. Prospective markets in everything: a vegetarian patty so similar to meat that it appears to bleed. And will one device change how we cook forever?

4. Amazon’s plan to fill the sky with drones and end the great stagnation.

5. The White House report on occupational licensing (pdf).

6. The game theory of Uber? (speculative)

Patent Trolls are Only the Symptom

I was going to write a post on how trolls aren’t the fundamental problem with the patent system but Timothy Lee has it covered:

…trolls aren’t the primary problem with the patent system. They’re just the problem Congress is willing to fix. The primary problem with the patent system is, well, the patent system. The system makes it too easy to get broad, vague patents, and the litigation process is tilted too far toward plaintiffs. But because so many big companies make so much money off of this system, few in Congress are willing to consider broader reforms.

A modern example is Microsoft, which has more than 40,000 patents and reportedly earns billions of dollars per year in patent licensing revenues from companies selling Android phones. That’s not because Google was caught copying Microsoft’s Windows Phone software (which has never been very popular with consumers). Rather, it’s because low standards for patents — especially in software — have allowed Microsoft to amass a huge number of patents on routine characteristics of mobile operating systems. Microsoft’s patent arsenal has become so huge that it’s effectively impossible to create a mobile operating system without infringing some of them. And so Microsoft can demand that smaller, more innovative companies pay them off.

… In effect, the patent system is acting as an innovation tax, transferring wealth from companies that are creating successful technologies today to companies that acquired a lot of patents a decade ago.

A more fundamental change would be to offer patents of varying length, say 3, 7, and 20 years with the understanding that 3 year patents will be approved quickly but 20 year patents will be required to leap a high hurdle on non-obviousness, prior art and so forth. See my paper Patent Theory versus Patent Law.

My video on patents is a quick and fun introduction.

Why TPP on IP law is better than you think

I have read and heard many times that TPP will bring harsher intellectual property law than is appropriate for the poorer Asian countries, noting that over time we can expect more of them to join the agreement. In general poorer countries often benefit from weaker IP enforcement, more copying, and lower prices. This is standard stuff.

It is less commonly recognized by the critics, however, that tougher IP protection may induce more foreign direct investment. Why for instance invest in a country which might subject your patents and copyrights to an undesired form of compulsory licensing? Trade agreements are likely to rule out or restrict such risks. There will be more cross-border licensing activity as well, if there is tougher IP enforcement. A company might even set up an R&D facility in a upper-tier developing country.

Carsten Fink and Kwith E. Maskus have an entire volume on these questions, Intellectual Property and Development. Here is one sample bit from their introduction (pdf):

IPRs are quite important for multinational firms making location decisions among middle-income countries with strong abilities to absorb and learn technology.

You will note however that the effect is not there for poorer countries. But in general:

…stronger IPRs have a significantly positive effect on total trade.

And this:

The study’s findings support a positive role for IPRs in stimulating enterprise development and innovation in developing countries.

I would say the volume, and the surrounding literature, as a whole provides some positive support for how IP rights may boost economic development, though not overwhelming or unambiguous support. And the literature does not support a “one size fits all” approach to IP law; in this sense TPP is far from ideal. But still, the literature does find some very real development benefits when a country moves to tougher IP rights.

But here’s the thing: TPP opponents simply tell us that bad and too tight IP law will be foisted upon the world’s economies. I see talk of Aaron Schwartz and Mickey Mouse extensions, but I don’t see enough of the critics weighing the costs and benefits, or for that matter even mentioning the possible benefits of extending IP regimes. I think the benefits of this IP extension may well outweigh the costs, when it comes to the developing nations involved in TPP. At the very least it seems to me up for grabs. And I certainly don’t think that voting down TPP this time around is going to lead to a more favorable redo of the agreement, not on IP for sure.

So IP considerations are not weighing nearly as much against TPP as you might think.

Assorted links

1. Michael Spence on whether equities are overvalued.

2. Does a year of NYU now cost $71,000?

3. 422 free art books from the Met.

4. Richard E. Wagner on Gordon Tullock, and more here. And are most occupational licensing boards now illegal?

5. What is the Chinese view of TPP?

Assorted links

1. Chemists find a way to unboil eggs. And the Obama administration targets occupational licensing.

2. Jodi Beggs example database for Principles of Economics course.

3. When writing about China, it is much easier to acknowledge the importance of the top one percent. A very good post, #moodaffiliation.

4. Afghan carpet weavers are putting drones on their rugs.

5. Will new technology lead to ultraropes, much longer elevator shafts, and much taller cities?

6. Why the left wing sometimes finds it hard to succeed, follow-up post here, I’m not saying you should read those through. And do more expensive placebos work better? Original paper here. And here is Ross Douthat on same.

7. People identified through credit card use alone, often as few as four transactions.

Our Guild-Ridden Labor Market

Could right and left unite in opposing occupational licensing? In an excellent primer Morris Kleiner makes the argument:

One unifying theme about the growth of occupational regulation has been the opposition from both the left and right of the political spectrum. Many on the left are concerned about the reduction in job opportunities, the increase in prices, and the diminished availability of services for those in or near poverty. On the right there is concern for economic liberty and access to the labor market and jobs. Many licensed professions are relatively low-skilled jobs, such as barbers, manicurists, nurse’s aides, and cosmetologists. The social costs of a bad haircut may be negligible, but the social costs of creating additional employment barriers for disadvantaged populations are not. Licensure laws often exclude ex-felons—defensible in many professions, but not in all, and such prohibitions make it extremely difficult for ex-offenders to find post-prison employment, thereby contributing to America’s high recidivism rate.

…If both the left and right oppose more occupational regulation, why is it growing? From the time of medieval guilds, service providers have had strong incentives to create barriers to entry for their professions in order to raise wages. In contrast, consumers who will be affected by the higher costs due to licensure are unorganized and arguably underrepresented in the political process.

Read the full post and Kleiner’s excellent book for many useful references. Here are previous MR posts on occupational licensing.