Results for “more police” 437 found

*Revolusi*

The subtitle is Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World, and the author is David van Reybrouck. An excellent book, and I found two points of particular interest in it. First, just how weak and incomplete was the Dutch colonization of Indonesia for centuries. Second, just how complicated and rapidly changing was the postwar transition from Japanese rule to independence. Excerpt:

In total no fewer than 120,000 Dutch conscripts would depart between 1946 and 1949, an enormous number that approached the general mobilization before World War II (150,000). Six thousand recruits who were examined and judged ‘fit for the tropics’ refused to embark. Many of these were tracked down and hauled out of beds to the military police. This hunt for deserters went on until 1958! Strict sentences were passed on 2,565 war resisters. Almost three-quarters received custodial sentences of up to two years, the rest remain in jail even longer. Altogether a total of fifteen centuries of prison sentences were pronounced, a remarkably large amount compared to the complete immunity granted to later war criminals. The conclusion was clear: those who refused to kill were locked up, those who murdered without reason went free.

Recommended, there should of course be more such books on Indonesia.

Pacific Heights: A Movie Ahead of Its Time

Pacific Heights is a 1990 movie starring Michael Keaton, Melanie Griffith, and Matthew Modine. Conventionally described as a “psychological thriller,” or a horror movie it’s actually a Kafkaesque analysis of tenancy rights and the legal system. The movie centers on a young couple, Drake and Patty, who purchase a San Francisco Victorian with dreams of fixing it up and renting several of the units to help pay the mortgage. Their dream turns into a nightmare when Carter Hayes (Michael Keaton) moves in and exploits tenant protection laws to torment and exploit them.

Hayes moves in without permission and without paying rent and he changes the locks. It doesn’t matter. When Drake (Modine) shuts off the power and heat, Hayes calls the police and the police explain to Drake:

What you did is against the law….turn the power and heat back on and apologize because according to the California civil code he has a right to sue and most likely he will win. If he’s in, he has rights, that’s how it works.

A lawyer later adds “He’s taken possession so whether he signed a lease or paid money or not he’s legally your tenant now and he is protected by laws that say you have to go to court to prove that he has to be evicted but the net effect of these laws is to…slowly drive you bankrupt and insane.”

What makes Pacific Heights a horror movie is that the tenant’s rights laws depicted are very real. Here’s just one example of thousands from NYC:

NEW: New York City homeowner gets arrested after changing the locks on *her own home* after it got taken over by squatters.

Never do business in New York.

In NYC, anyone can simply claim "squatter's rights" after 30 days of living at a home which isn't even enough time for the… pic.twitter.com/xkcfYM9l7u

— Collin Rugg (@CollinRugg) March 19, 2024

As I wrote on twitter “Decades of anti-landlord legislation has created a moocher-class of squatters who steal homes and then call the police on the owners.” Moreover, even today such laws continue to be added to the books. A bill in Congress, for example, would prevent landlords from being able to screen tenants for criminal records.

All of this has been exacerbated recently by COVID laws preventing eviction (some of which remain but which acclimatized some tenants to not paying rent and contributed to court backlogs), court backlogs and the greater ease of finding unoccupied houses using foreclosure data, death announcements, Zillow and so forth. In extreme cases it can take decades to evict a squatter who uses the law to their advantage.

Returning to Pacific Heights, what the movie gets wrong is the second half where Patty (Melanie Griffith) extracts revenge against Hayes. A less cathartic but more accurate ending would have had the couple exhausted with the complexities of tenant law and the court system and finally giving up when they realize that the law is not for them. Instead, they pay Carter Hayes a ransom to leave their own home. Of course, Drake and Patty choose never to rent to anyone ever again.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Are more stable rock bands more likely to be successful?

2. Harvard will not proceed with its geoengineering experiment. I think you can guess why not.

3. The Zvi on Devin.

4. Is there ever a labor market motherhood premium?

5. Mysteries of the Gardner Museum theft (NYT).

6. “Police Scotland’s officers are being told they should target actors and comedians under Scotland’s new hate crime laws.” (mostly gated, you can read a bit of it)

7. Regulatory arbitrage, tech no-mergers edition.

8. Noah on various matters, including the Canadian economy (I think he is putting too much weight on the last two years, no doubt they are in a downturn).

Access to Medical Data Saves Lives

ProPublica: In January, the Biden administration pledged to increase public access to a wide array of Medicare information to improve health care for America’s most sick and vulnerable.

…So researchers across the country were flummoxed this week when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced a proposal that will increase fees and diminish access to claims data that has informed thousands of health care studies and influenced major public health reforms.

Using big Medicare databases has never been cheap or easy. Under the current system, researchers could have the data transferred to secure university computers for about $20,000–that’s a lot but once the data was on the university computers it could be accessed by multiple researchers, cutting costs. A professor could buy the data and their PhD students, for example, wouldn’t have to pay again. Under the new system it will cost $35,000 for one researcher to access the data which will be held on government (CMS) computers. Moreover, it’s unclear how complex statistical analysis will be performed or how congested the CMS systems may become.

Research teams on complex projects can include dozens of people and take years to complete. “The costs will grow exponentially and make access infeasible except for the very best resourced organizations,” said Joshua Gottlieb, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy.

Public data should be open access to researchers, with appropriate anonymization. We know from IP law that barriers to access reduce research and innovation; and in the medical sphere research and innovation saves lives. Open access is also a check on how governments spends taxpayer money and the effectiveness of such spending. I also worry that raising the dollar cost of access is a prelude to other restrictions. The NIH, for example, is restricting access to genetic data if it thinks the researcher will be asking forbidden questions. Even without such explicit restrictions, there is a chilling effect when researchers are beholden for access to the government and indeed to the very agencies they may be researching.

I place a high value on privacy but I get suspicious when governments invoke privacy to block citizen access to government data but not to block government access to citizen data. Medicare databases have always been appropriately anonymized and care is taken so the data are secured but the dangers of these databases in anyone’s hand, let alone researchers, is far less than anti-money laundering, KYC laws and suspicious transaction reports in banking, automated license plate readers that the police us to scan billions of license plates or mass surveillance of the communications of US citizens under FISA. Sadly, this list could easily be extended. Liberty thrives on the people’s privacy and the government’s transparency.

Is El Salvador special?

But Bukele copycats and those who believe his model can be replicated far and wide overlook a key point: The conditions that allowed him to wipe out El Salvador’s gangs are unlikely to jointly appear elsewhere in Latin America.

El Salvador’s gangs were unique, and far from the most formidable criminal organizations in the entire region. For decades, a handful of gangs fought one another for control of territory and became socially and politically powerful. But, unlike cartels in Mexico, Colombia and Brazil, El Salvador’s gangs weren’t big players in the global drug trade and focused more on extortion. Compared to these other groups, they were poorly financed and not as heavily armed.

Mr. Bukele started to deactivate the gangs by negotiating with their leaders, according to Salvadoran investigative journalists and a criminal investigation led by a former attorney general. (The government denies this.) When Mr. Bukele then arrested their foot soldiers in large sweeps that landed many innocent people in prison, the gangs collapsed.

It would not be such a simple story elsewhere in Latin America, where criminal organizations are wealthier, more internationally connected and much better armed than El Salvador’s gangs once were. When other governments in the region have tried to take down gang and cartel leaders, these groups haven’t simply crumbled. They have fought back, or new criminal groups have quickly filled the void, drawn by the drug trade’s huge profits. Pablo Escobar’s war on the state in 1980s-90s Colombia, the backlash by cartels to Mexican law enforcement activity since the mid-2000s, and the violent response to Ecuador’s government’s recent moves against gangs are just a few examples.

El Salvador also had more formidable and professional security forces, committed to crushing the gangs when Mr. Bukele called on them, than some of its neighbors. Take Honduras, where gang-sponsored corruption among security forces apparently runs deep. That helped doom Ms. Castro’s attempts to emulate Mr. Bukele from the start. In other countries, like Mexico, criminal groups have also reportedly managed to co-opt high-ranking members of the military and police. In Venezuela, it has been reported that military officials have run their own drug trafficking operation. Even if presidents send soldiers and police to do Bukele-style mass roundups, security forces may not be prepared, or may have incentives to undermine the task at hand.

Here is more from Will Freeman and (NYT), interesting throughout.

The economics of illicit sand markets

Very few people are looking closely at the illegal sand system or calling for changes, however, because sand is a mundane resource. Yet sand mining is the world’s largest extraction industry because sand is a main ingredient in concrete, and the global construction industry has been soaring for decades. Every year the world uses up to 50 billion metric tons of sand, according to a United Nations Environment Program report. The only natural resource more widely consumed is water. A 2022 study by researchers at the University of Amsterdam concluded that we are dredging river sand at rates that far outstrip nature’s ability to replace it, so much so that the world could run out of construction-grade sand by 2050. The U.N. report confirms that sand mining at current rates is unsustainable.

And:

Most sand gets used in the country where it is mined, but with some national supplies dwindling, imports reached $1.9 billion in 2018, according to Harvard’s Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Companies large and small dredge up sand from waterways and the ocean floor and transport it to wholesalers, construction firms and retailers. Even the legal sand trade is hard to track. Two experts estimate the global market at about $100 billion a year, yet the U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries indicates the value could be as high as $785 billion. Sand in riverbeds, lake beds and shorelines is the best for construction, but scarcity opens the market to less suitable sand from beaches and dunes, much of it scraped illegally and cheaply. With a shortage looming and prices rising, sand from Moroccan beaches and dunes is sold inside the country and is also shipped abroad, using organized crime’s extensive transport networks, Abderrahmane has found. More than half of Morocco’s sand is illegally mined, he says.

Of course these are usually unowned, unpriced resources:

Luis Fernando Ramadon, a federal police specialist in Brazil who studies extractive industries, estimates that the global illegal sand trade ranges from $200 billion to $350 billion a year—more than illegal logging, gold mining and fishing combined. Buyers rarely check the provenance of sand; legal and black market sand look identical. Illegal mining rarely draws heat from law enforcement because it looks like legitimate mining—trucks, backhoes and shovels—there’s no property owner lodging complaints, and officials may be profiting. For crime syndicates, it’s easy money.

Here is the full Scientific American piece by David A. Taylor.

Get Out of Jail Cards, 2

“Courtesy cards,” are cards given out by the NYC police union (and presumably elsewhere) to friends and family who use them to get easy treatment if they are pulled over by a cop. I was stunned when I first wrote about these cards in 2018. I thought this was common only in tinpot dictatorships and flailing states. The cards even come in levels, gold, silver and bronze!

A retired police officer on Quora explains how the privilege is enforced:

The officer who is presented with one of these cards will normally tell the violator to be more careful, give the card back, and send them on their way.

…The other option is potentially more perilous. The enforcement officer can issue the ticket or make the arrest in spite of the courtesy card. This is called “writing over the card.” There is a chance that the officer who issued the card will understand why the enforcement officer did what he did, and nothing will come of it. However, it is equally possible that the enforcement officer’s zeal will not be appreciated, and the enforcement officer will come to work one day to find his locker has been moved to the parking lot and filled with dog excrement.

A NYTimes article discusses the case of Mathew Bianchi, a traffic cop who got sick of letting dangerous speeders go when they presented their cards.

By the time he pulled over the Mazda in November 2018, drivers were handing Bianchi these cards six or seven times a day. (!!!, AT)

…[He gives the ticket]…The month after he stopped the Mazda, a high-ranking police union official, Albert Acierno, got in touch. He told Bianchi that the cards were inviolable. He then delivered what Bianchi came to think of as the “brother speech,” saying that cops are brothers and must help each other out. That the cards were symbols of the bonds between the police and their extended family and friends.

Bianchi was starting to view the cards as a different kind of symbol: of the impunity that came with knowing someone on the force, as if New York’s rules didn’t apply to those with connections. Over the next four years, he learned about the unwritten rules that have come to hold sway in the Police Department.

Bianchi is reassigned, given shit jobs, isn’t promoted etc. Mayor Adams and police chief Chief Maddrey protect this utterly corrupt system.

Freedom of speech for university staff?

Put aside the more virtuous public universities, where such matters are governed by law. What policies should private universities have toward freedom of speech for university staff? This is not such a simple question, even if you are in non-legal realms a big believer in de facto freedom of speech practices.

Just look at companies or for that matter (non-university) non-profits. How many of them allow staff to say whatever they want, without fear of firing? What if a middle manager at General Foods went around making offensive (or perceived to be offensive) remarks about other staff members? Repeatedly, and after having been told to stop. There is a good chance that person will end up fired, even if senior management is not seeking to restrict speech or opinion per se. Other people on the staff will object, and of course some of the offensive remarks might be about them. The speech offender just won’t be able to work with a lot of the company any more. Maybe that person won’t end up fired, but would any companies restrict their policies, ex ante, to promise that person won’t be fired? Or in any way penalized, set aside, restricted from working with others or from receiving supervisory promotions, and so on?

You already know the answers to those questions.

Freedom of speech for university staff is a harder question than for students or faculty. Students will move on, and a lot of faculty hate each other anyway, and don’t have to work together very much. Plus the protection of tenure was (supposedly?) designed to support freedom of speech and opinion, even “perceived to be offensive” opinions. As for students, we want them to be experimenting with different opinions in their youth, even if some of those opinions are bad or stupid. Staff in these regards are different.

Staff are growing in numbers and import at universities. They often are the leaders of Woke movements. Counselors, Director of Student Affairs, associate Deans, and much more. Then there are the events teams and the athletic departments, and more yet. Perhaps some schools spend more on staff than on faculty?

While it is hard to give staff absolute free speech rights, it is also hard to give them differential free speech rights. A cultural tone is set within the organization. If everyone else has free speech rights, how exactly do you enforce restrictions on staff? Should a university set up a “thought police” but for staff only? Can you really circumscribe the powers of such a thought police over time? Besides, what if a staff member signs up for a single night course? Do they all of a sudden have the free speech rights of students? How might you know when they are “speaking as a student” or “speaking as a staff member”? Or what if staff are overseeing the free speech rights of faculty and students, as is pretty much always the case? The enforcers of student free speech rights don’t have those same free speech rights themselves? What kind of culture are they then being led to respect and maintain? And what if staff are merely expressing their opinions off-campus, say on their Facebook pages? Does all that get monitored? Or do you simply encourage one set of people to selectively complain about another set, as a kind of weaponization of some views but not others?

You might have your own theoretical answers to these conundrums, but the cultural norms of large institutions usually aren’t finely grained enough to support them all.

If you think that free speech rights for university staff are an easy question, I submit you haven’t thought about this one long and hard enough.

Immigration Backlash

In a new paper Ernesto Tiburcio (on the job market) and Kara Ross Camarena study the effect of illegal immigration from Mexico on economic, political and cultural change in the United States. Studying illegal immigration can be difficult because the US doesn’t have great ways of tracking illegal immigrants. Tiburcio and Camerena, however, make excellent use of a high-quality dataset of “consular IDs” from the Mexican government. Consular IDs are identification cards issued by the Mexican government to its citizens living in the United States, regardless of US immigration status. Consular IDs are used especially, however, by illegal immigrants because they can’t easily get US IDs whereas legal migrants have passports, visas, work authorizations and so forth. Tiburcio and Camarena are able to track nearly 8 million migrants over more than a decade.

Our main results point to a conservative response in voting and policy. Recent inflows of unauthorized migrants increase the vote share for the Republican Party in federal elections, reduce local public spending, and shift it away from education towards law-and-order. A mean inflow of migrants (0.4 percent of the county population) boosts the Republican party vote share in midterm House elections by 3.9 percentage points. Our results are larger but qualitatively similar to other scholars’ findings of political reactions to migration inflows in other settings (Dinas et al., 2019; Dustmann et al., 2019; Harmon, 2018; Mayda et al., 2022a). The impacts on public spending are consistent with the Republican agenda. A smaller government and a focus on law-and-order are two of the key tenets of conservatism in the US. A mean inflow of migrants reduces total direct spending (per capita) by 2% and education spending (per child), the largest budget item at the local level, by 3%. The same flow increases relative spending on police and on the administration of justice by 0.23 and 0.15 percentage points, respectively. These impacts on relative spending suggest that the decrease in total expenditure does not simply reflect a reduction in tax revenues but also a conservative change in spending priorities.

The main reason for this, however, appears not to be economic losses such as job losses or wages declines–these are mostly zero or small with some exceptions for highly specific industries such as construction. Rather it’s more about the salience of in and out groups:

We study individuals’ universalist values to capture preferences for redistribution and openness to the out-group. Universalist values imply that one is concerned equally with the welfare of all individuals, whether they are known or not. By contrast, people with more communal values assign a greater weight to the welfare of ingroup members relative to out-group members. We find that counties become less universalist in response to the arrival of new unauthorized migrants. A mean flow of unauthorized migrants shifts counties 0.06 standardized units toward less universalist, i.e., more communal (Panel B, Column 5, std coeff: -0.16). This result is the most direct indication that some of the shift to the political right occurs because migrants trigger anti-out-group bias and preferences for less redistribution. Although this evidence is based on a smaller subset of counties, the impact is large. The change toward more communal values is consistent with theories that hinge on out-group bias. Ethnic heterogeneity breaks down trust, makes coordination more difficult, and reduces people’s interest in universal redistribution (Alesina et al., 1999).

These results are consistent with the larger literature that finds “Across the developed world today, support for welfare, redistribution, and government provision of public goods is inversely correlated with the share of the population that is foreign-born and diverse.” (Nowrasteh and Forreseter 2020). Similarly, one explanation for the smaller US welfare state is that white-black salience reduces people’s interest in universal redistribution.

Contra Milton Friedman, it is possible to have open borders and a significant welfare state but it may be true that the demand for a welfare state declines with immigration, especially when the immigrants are saliently different.

The Indian Challenge to Blockchains: Digital Public Goods

In my post, Blockchains and the Opportunity of the Commons, I explored the potential of blockchains to create new commons:

Blockchains and tokenization are a way to incentivize the creation of a commons. A commons is an unowned place, platform, or protocol that helps people to meet, communicate and transact. Commons underlying modern life include TCP/IP, SMTP, HTTP, GPS and the English language. We don’t see these commons clearly because they are free, ubiquitous and, like air, taken for granted. What we do see are platforms like Airbnb, Uber and the NYSE and places to meet and communicate like OkCupid, Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. What blockchain and tokenization offer is the possibility of creating commons to replace all of these services and much more.

For the most part, the potential has not been realized. But the core idea of substituting a protocol for a firm has been taken in a different direction in India. Instead of blockchains, India has been experimenting with digital public goods. A digital public good is open source software with open data and open standards–available for use or even modification and adaption by anyone. The blockchain community, for example, has long aspired to develop a blockchain-based Uber, connecting drivers and riders without a corporate intermediary. India has achieved this through digital public goods instead.

Namma Yatri is an open-source, open-data Uber-like protocol with 100% of the commission flowing directly from rider to driver. Namma Yatri is built on the Beckn Protocol, a product of the Beckn Foundation which is backed by Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani (Tyler and I had the opportunity to talk with many people behind the project including Nandan on a recent trip to India). Namma Yatri has booked over 15 million trips in just one year of operation, mostly in one city, Bangalore. I expect it will expand rapidly.

Namma Yatri is only one example of a digital public good in the India Stack, a collection that includes identity (Aadhaar), payments (UPI) and digital data sharing (e.g. digital lockers). Since its launch in 2008, for example, India’s Aadhaar system has created a digital identity for over 1.2 billion people allowing them to open some 650 million bank accounts. This has enhanced financial inclusion and facilitated direct government payments of pensions and rations, reducing corruption. Likewise, the UPI system built modern payment rails which are then leveraged by banks and firms such as Google Pay and WhatsApp. The resulting payments system does some 10 billion transactions a month and is one of the fastest and lowest cost in the world.

Challenges remain. The development of digital public goods relies on funding from non-profits, governments, and private consortiums, raising questions about long-term sustainability. These goods need regular maintenance and updates, and some require backend support. Namma Yatri began as a completely free app for drivers and users but if there is a problem who do you call? To support the back-end office, and to pay for updated inputs (such as maps) the service has started to use a subscription fee. Nothing wrong with that but it’s a reminder that firms are not so easily dispensed with. Privacy is another concern. While blockchains offer privacy at the technology layer, privacy for digital public goods depend on legal and normative frameworks. For instance, India’s Aadhaar system is legally restricted from police use, a smart balance that needs to be maintained in changing times.

Despite these challenges, there is no denying that India has built digital public goods at scale in a way that demonstrates an alternative pathway for digital infrastructure and a challenge to blockchains.

My Conversation with Githae Gitinji

This is a special bonus episode of CWT, Githae is a 58-year-old village elder who mediates disputes and lives in Tatu City, Kenya, near Nairobi. Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

In his conversation with Tyler, Githae discusses his work as a businessman in the transport industry and what he looks for when hiring drivers, the reasons he moved from his rural hometown to the city and his perspectives on urban vs rural living, Kikuyu cultural practices, his role as a community elder resolving disputes through both discussion and social pressure, the challenges Kenya faces, his call for more foreign investment to create local jobs, how generational attitudes differ, the role of religion and Githae’s Catholic faith, perspectives on Chinese involvement in Kenya and openness to foreigners, thoughts on the devolution of power to Kenyan counties, his favorite wildlife, why he’s optimistic about Kenya’s future despite current difficulties, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: What do you do that the court system does not do? Because you’re not police, but still you do something useful.

GITHINJI: What we normally do, we as a group, we listen to one another very much. When one person reaches that stage of being told that you are a man now, you normally have to respect your elder. Those people do respect me. When I call you, when I tell you “Come and we’ll talk it out,” with my group, you cannot say you cannot come, because if you do, we normally discipline somebody. Not by beating, we just remove you from our group. When we isolate you from our group, you’ll feel that is not fair for you. You come back and say — and apologize. We take you back into the group.

COWEN: If you’re isolated, you can’t be friends with those people anymore.

GITHINJI: When we isolate you, we mean you are not allowed to interact in any way.

COWEN: Any way.

GITHINJI: Any business, anything with the other community [members]. If it is so, definitely, you have to be a loser, because you might be needing one of those people to help you in business or something of the sort. When you are isolated, this man tells you, “No. Go and cleanse yourself first with that group.”

If you find his Kikiyu accent difficult, just read the transcript instead. This episode is best consumed in a pair with my concurrently recorded episode with Harriet Karimi Muriithi, a 22-year-old Kenyan waitress — the contrasts in perspective across a mere generation are remarkable.

Sunday assorted links

Market Response to Racial Uprisings

Defund the police was never really in the cards:

Do investors anticipate that demands for racial equity will impact companies? We explore this question in the context of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement—the largest racially motivated protest movement in U.S. history—and its effect on the U.S. policing industry using a novel dataset on publicly traded firms contracting with the police. It is unclear whether the BLM uprisings were likely to increase or decrease market valuations of firms contracting heavily with police because of the increased interest in reforming the police, fears over rising crime, and pushes to “defund the police”. We find, in contrast to the predictions of economics experts we surveyed, that in the three weeks following incidents triggering BLM uprisings, policing firms experienced a stock price increase of seven percentage points relative to the stock prices of nonpolicing firms in similar industries. In particular, firms producing surveillance technology and police accountability tools experienced higher returns following BLM activism–related events. Furthermore, policing firms’ fundamentals, such as sales, improved after the murder of George Floyd, suggesting that policing firms’ future performances bore out investors’ positive expectations following incidents triggering BLM uprisings. Our research shows how—despite BLM’s calls to reduce investment in policing and explore alternative public safety approaches—the financial market has translated high-profile violence against Black civilians and calls for systemic change into shareholder gains and additional revenues for police suppliers.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Bocar A. Ba, Roman Rivera, and Alexander Whitefield.

My excellent Conversation with Peter Singer

Here is the video, audio, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Peter joined Tyler to discuss whether utilitarianism is only tractable at the margin, how Peter thinks about the meat-eater problem, why he might side with aliens over humans, at what margins he would police nature, the utilitarian approach to secularism and abortion, what he’s learned producing the Journal of Controversial Ideas, what he’d change about the current Effective Altruism movement, where Derek Parfit went wrong, to what extent we should respect the wishes of the dead, why professional philosophy is so boring, his advice on how to enjoy our lives, what he’ll be doing after retiring from teaching, and more.

Peter described it as “like aerobics for the brain.” Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: How much should we spend trying to thwart predators?

SINGER: I think that’s difficult because, again, you would have to take into account the consequences of not having predators, and what are you going to do with a prey population? Are they going to overpopulate and maybe starve or destroy the environment for other sentient beings? So, it’s hard to say how much we should spend trying to thwart them.

I think there are questions about reducing the suffering of wild animals that are easier than that. That’s a question that maybe, at some stage, we’ll grapple with when we’ve reduced the amount of suffering we inflict on animals generally. It’s nowhere near the top of the list for how to reduce animal suffering.

COWEN: What do you think of the fairly common fear that if we mix the moralities of human beings and the moralities of nature, that the moralities of nature will win out? Nature is so large and numerous and populous and fierce. Human beings are relatively small in number and fragile. If the prevailing ethic becomes the ethic of nature, that the blending is itself dangerous, that human beings end up thinking, “Well, predation is just fine; it’s the way of nature.” Therefore, they do terrible things to each other.

SINGER: Is that what you meant by the moralities of nature? I wasn’t sure what the phrase meant. Do you mean the morality that we imply, that we attribute to nature?

COWEN: “Red in tooth and claw.” If we think that’s a matter that is our business, do we not end up with that morality? Trumping ours, we become subordinate to that morality. A lot of very nasty people in history have actually cited nature. “Well, nature works this way. I’m just doing that. It’s a part of nature. It’s more or less okay.” How do we avoid those series of moves?

SINGER: Right. It’s a bad argument, and we try and explain why it’s a bad argument, that we don’t want to follow nature. That the fact that nature does something is not something that we ought to imitate, but maybe, in fact, we ought to combat, and of course, we do combat nature in many ways. Maybe war between humans is part of nature, but nevertheless, we regret when wars break out. We try to have institutions to prevent wars breaking out. I think a lot of our activities are combating nature’s way of doing things rather than regarding it as a model to follow.

COWEN: But if humans are a part of nature flat out, and if our optimal policing of nature leaves 99.9999 percent of all predation in place — we just can’t stop most of it — is it then so irrational to conclude, “Well this predation must be okay. It’s the natural state of the world. Our optimal best outcome leaves 99.99999 percent of it in place.” How do we avoid that mindset?

Recommended. And the new edition (much revised) of Peter’s Animal Liberation is now out.

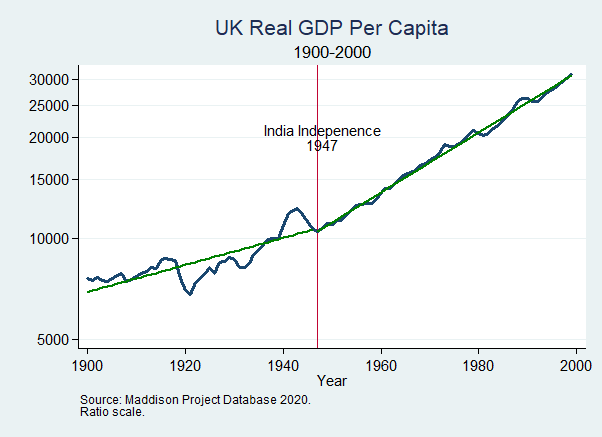

Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and a scant ten years later, India gained its independence. Thus, we have a clear prediction. Was England reduced to living mainly on herrings and potatoes after Indian Independence? No. In fact, not only did the UK continue to get rich after the end of empire, the growth rate of GDP increased.

Orwell’s failed prediction stemmed from two reasons. First, he was imbued with zero-sum thinking. It should have been obvious that India was not necessary to the high standard of living enjoyed in England because most of that high standard of living came from increases in the productivity of labor brought about capitalism and the industrial revolution and most of that was independent of empire (Most. Maybe all. Maybe more more than all. Maybe not all. One can debate the finer details on financing but of that debate I have little interest.) The second, related reason was that Orwell had a deep suspicion and distaste for technology, a theme I will take up in a later post.

Orwell, who was born in India and learned something about despotism as a police officer in Burma, opposed empire. Thus, his argument that we had to be poor to be just was a tragic dilemma, one of many that made him pessimistic about the future of humanity.