Results for “prediction market” 326 found

Are we approaching labor market equilibrium?

After four years in which pay failed to keep pace with price

increases, wages for most American workers have begun rising

significantly faster than inflation.With energy prices

now sharply lower than a few months ago and the improving job market

forcing employers to offer higher raises, the buying power of American

workers is now rising at the fastest rate since the economic boom of

the late 1990s.The average hourly wage for workers below

management level – everyone from school bus drivers to stockbrokers –

rose 2.8 percent from October 2005 to October of this year, after being

adjusted for inflation, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Only a year ago, it was falling by 1.5 percent.

Productivity has been rising for years, so it is comforting to see wages follow suit. Every now and then the predictions of economic theory are correct.

Here is the full story. The timing of this news could not be better, if you get my drift…

Nobel Prize predictions

The Economics prize will be announced October 9. Here are speculations from last year. Here are further plausible picks. Gordon Tullock deserves it. I predict Eugene Fama and Richard Thaler as deserving co-winners for their work in empirical finance. Fama will win it for first proving (1972) and then disproving (1992) CAPM, the Capital Asset Pricing Model. Thaler will win it for developing behavioral finance and a better account of how irrationalities manifest themselves in asset markets. Kenneth French, a co-author of Fama’s, might be a third pick. My greatest fear is that they pick Lars Svensson (I believe he is Norwegian, but still that is not a bad name for winning a Swedish prize), and somebody asks me to explain his work.

I believe I have never once predicted this prize correctly. Last year I said Thomas Schelling, the co-winner with Bob Aumann, deserved the prize but might not ever get it. What do you all think?

Addendum: Chris Masse points me to bookie odds on the Peace Prize.

Why are markets in exercise discipline imperfect?

Exercise is statistically correlated with better health, but weight is not. That suggests you should exercise more. Furthermore some exercise is much better than no exercise at all, so you can be happy with a modest achievement.

Why don’t we rely more on markets to force ourselves to exercise?

Post a bond with your friend, your spouse, your exercise partner, or someone you won’t (or can’t) lie to. You lose the money if you don’t exercise according to a pre-arranged plan with well-defined quantitative goals. If need be, I will serve in this role and cash your check when it comes in the mail (hey, would you lie to your blogger?).

Or why not have the gym collect a bigger upfront fee, and they pay you each time you show up and complete an exercise program under their supervision?

What are the problems with these arrangements?

1. The roles of friend or spouse do not mix with that of "Enforcer." That being said, I bet your spouse is willing to enforce her requirements on you. And surely she wants you to live longer, so why not extend the scope of her enforcement just a wee bit?

2. The payment, if you lose, is not a real transfer. You share funds with your spouse and your friend will treat is as a gift to be returned. Fair enough, but then find a real bastard, a corporation, or an amiable but distant blogger.

3. You enjoy exercise, but not if you feel obliged to do it. Introducing too many external incentives takes away the possibility of developing internal motivation. (Similarly, if you pay your kid to do the dishes, she will no longer feel obliged and the total quantity of labor may fall.) If the exercise arena becomes a regular sphere of money loss and humiliation, you will avoid the exercise idea altogether. After a while you will stop making these contracts.

4. You don’t really want to exercise more in the first place.

I put most of my money on #3.

We hear all this superficial blather about "life being a process." This is true, but it is less well-recognized that this is a source of institutional failure. Most good things you do — and I include charity on this list — you do not for the ends themselves, but because you have somehow managed to enjoy the process of regular engagement and self-discipline. You then deceive yourself into thinking you value the end more than you do. This creates social order, but it also makes those same commitments fragile. Whether you are meta-rational or not, you are unlikely to seek brutal market discipline (or advice columnists, for that matter) to enforce your good behavior. You prefer to play the happy fool, even though you will die earlier and refuse to break up with the creep you are currently dating, no matter how many of your friends tell you he is ultimately a loser.

The alternative methods?: Fantasize about the relationship between exercise and more and better sex, whether or not it is there at the margins you face. Build fantasy upon fantasy to make the area a source of fun. Or try self-prophecy.

Addendum: Economist Art DeVany has intricate theories about exercise, based on his understanding of evolutionary biology. Run sprints, not marathons. Art reports on his blog how devastated he is from the recent death of his wife; do read this moving tale.

Terror Betting Markets and the 9/11 Commission

Remember “terrorism betting markets”? The program was killed one day after it made headlines – so much for democratic inertia! Opponents plausibly argued that these markets made terrorism pay. According to a press release by Senators Wyden and Dorgan:

Terrorists themselves could drive up the market for an event they are planning and profit from an attack, or even make false bets to mislead intelligence authorities.

Of course, you hardly need terrorism betting markets to make money from terrorism; all you need to do is short the stocks of firms that will be adversely affected (say… airlines?). So if betting on terrorism scares you, you should still be scared! But before you start losing sleep, check out the findings of the 9/11 Commission. They find no evidence of 9/11-related stock market manipulation. Here are the two key passages:

There also have been claims that al Qaeda financed itself through

manipulation of the stock market based on its advance knowledge of the 9/11

attacks. Exhaustive investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission,

FBI, and other agencies have uncovered no evidence that anyone with advance

knowledge of the attacks profited through securities transactions. (pp.171-2)

Highly publicized allegations of insider trading in advance of 9/11 generally rest on reports of unusual

pre-9/11 trading activity in companies whose stock plummeted after the attacks. Some unusual trading did in fact

occur, but each such trade proved to have an innocuous explanation. For example, the volume of put options–

investments that pay off only when a stock drops in price–surged in the parent companies of United Airlines on

September 6 and American Airlines on September 10–highly suspicious trading on its face. Yet, further investigation

has revealed that the trading had no connection with 9/11. A single U.S.-based institutional investor with no

conceivable ties to al Qaeda purchased 95 percent of the UAL puts on September 6 as part of a trading strategy

that also included buying 115,000 shares of American on September 10… The SEC and the FBI, aided by other agencies and the securities industry, devoted enormous

resources to investigating this issue, including securing the cooperation of many foreign governments. These

investigators have found that the apparently suspicious consistently proved innocuous. (p.499)

It is worth pointing out that even if the 9/11 Commission had found evidence of a terror/stock market connection, there would still be almost no case against the original plan for terrorism betting markets. The maximum bet was under $100. I like the economic theory of suicide as much as the next economist, but I still can’t imagine any would-be terrorist changing his mind over a Benjamin.

Thanks to my colleague and terrorism betting market lightning rod Robin Hanson for the 9/11 pointer. See also Alex’s short piece In Defense of Prediction Markets, kindly made available by Mahalanobis.

Markets in everything – Korean women edition

This time courtesy of the ever-insightful Randall Parker. Here is one juicy bit:

Chinese men may buy so many North Korean wives that North Korea will either become militarily aggressive or collapse from within. This is not implausible. Those 30 to 40 million single men in China in the year 2020 mean there wil be 3 to 4 times more single men in China than there are women in North Korea. The Chinese will be more affluent than the North Koreans unless radical changes happen to North Korea’s economy. North Korea is the place where Chinese men will have the best competitive advantage in angling for wives. The other East Asian countries are not nearly as poor as North Korea and North Korea shares a long 1,416 km land border with China.

China’s economy is growing rapidly. The buying power of Chinese men is rising. Even poor Chinese farmers can afford to buy North Korean women.

And what is Randall’s prediction?

Expect the hostility of North Korean men toward China to increase.

Good call, Randall!

Food predictions and pronouncements

I very much enjoyed giving the keynote address to the International Association of Culinary Professionals. But this was not a crowd that wanted to hear about standard errors, or indeed numbers of any sort. They wanted raw predictions and proclamations. Here is an edited sample of what I offered up:

1. Fast food will get much better, and soon.

2. Look to eat in strip malls, not shopping malls. Low rents encourage culinary experimentation and attract immigrants.

3. America’s culinary profile is defined increasingly by ethnicity and demographics, not by geographic region.

4. French cooking, for all its virtues, is stagnating.

5. The UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are all up-and-coming culinary hotspots.

And what about investment advice?

That’s what economists are really good for, no? And no one wants to hear that you believe in the weak form of the efficient markets hypothesis.

Put on the spot, I offered the following principle. If sushi restaurants are new to a country, and are succeeding, buy shares in the stocks of that country. Raw fish, of course, can be toxic. Quality can be hard to monitor with the naked eye. Sushi consumption is a sign that people are starting to trust each other.

Vitalik on AI and crypto

…we can expect to see in the 2020s that we did not see in the 2010s: the possibility of ubiquitous participation by AIs.

AIs are willing to work for less than $1 per hour, and have the knowledge of an encyclopedia – and if that’s not enough, they can even be integrated with real-time web search capability. If you make a market, and put up a liquidity subsidy of $50, humans will not care enough to bid, but thousands of AIs will easily swarm all over the question and make the best guess they can. The incentive to do a good job on any one question may be tiny, but the incentive to make an AI that makes good predictions in general may be in the millions. Note that potentially, you don’t even need the humans to adjudicate most questions: you can use a multi-round dispute system similar to Augur or Kleros, where AIs would also be the ones participating in earlier rounds. Humans would only need to respond in those few cases where a series of escalations have taken place and large amounts of money have been committed by both sides.

This is a powerful primitive, because once a “prediction market” can be made to work on such a microscopic scale, you can reuse the “prediction market” primitive for many other kinds of questions:

- Is this social media post acceptable under [terms of use]?

- What will happen to the price of stock X (eg. see Numerai)

- Is this account that is currently messaging me actually Elon Musk?

- Is this work submission on an online task marketplace acceptable?

- Is the dapp at https://examplefinance.network a scam?

- Is

0x1b54....98c3actually the address of the “Casinu Inu” ERC20 token?You may notice that a lot of these ideas go in the direction of what I called “info defense” in .

There are many other points, such as AIs as oracles, read it here, interesting throughout.

Monday assorted links

Saturday assorted links

1. The Mechanical Turk is increasingly mechanical in fact.

2. Participating in a climate prediction market increases concern about global warming.

4. Taliban markets in everything, “Cash-strapped Taliban selling tickets to ruins of Buddhas it blew up.”

5. Guess who is being blamed for high rates of Swedish inflation?

6. SpaceX hires fourteen-year-old engineer, he is then denied a LinkedIn account.

7. Ross on C.S. Lewis and the weirdness of our time (NYT). Good Straussian clincher at the very end.

8. Daniel Ellsberg, RIP (NYT).

Tabarrok on Stranded Technologies Podcast

I talk with entreprenreur Niklas Anzinger on the Stranded Technlogies Podcast. Niklas summarizes some of the discussion:

- This episode is an intellectual journey that discovers insights that can be used by entrepreneurs and city developers. We talk about the Baumol effect that Alex uses to explain the now infamous price chart.

- Alex’s recommendation to new city or governance startups like Prospera, Ciudad Morazan or the Catawba DEZ is to think of city development as a “dance between centralization and decentralization”.

- Economists have developed concepts that are waiting to be commercialized, e.g. prediction markets. In this episode, we talk about dominant assurance contracts and how they could be used in new city developments and fundraising.

Wednesday assorted links

Sunday assorted links

1. Encyclopedia Britannica commercial from 1988.

2. Lab Leak translation squabbles.

3. What predicts Wordle cheating.

4. GPT-3 answers Cowen-Gross interview questions.

5. Best article I’ve seen on prediction market issues in DC (FT). Here is another (ungated) article.

6. Vitalik on crypto regulation.

7. Can Jack White name any Beatles song from one second of the music?

8. Is Harpy the largest eagle in the world?

9. Drone proliferation, what did they say about the next world war being fought with sticks and stones?

*Risky Business*

The subtitle is Why Insurance Markets Fail and What To Do About It, and the authors are the highly regarded Liran Einav, Amy Finkelstein, Ray Fisman. The level is a bit above what could make this book a bestseller, but I consider that a good thing. The book in fact is a classic example of how to present economic research in readable, digestible form and should be regarded as such.

I do have a few qualms, but please note these are outweighed by the very high quality of the core material:

1. I think the authors underestimate how rapidly “Big Data” is shifting the information asymmetries away from consumers/policyholders. This is related to my recent remarks on AI.

1b. For reasons stemming from #1, insurance/surveillance/control, including from employers, will rise in importance as an issue, and soon. I don’t get a sense of that from reading this book. We might alleviate selection problems, while creating other difficulties including ethical dilemmas.

2. I would like to see more on moral hazard.

3. I also would want to see more — much more — on the public choice reasons why government insurance markets so often fail — the authors should consider their own title! Should the Florida government really be propping up insurance contracts and insurance markets to protect homeowners against climate change-related losses? No matter what your view, this kind of issue is under-discussed. How about the FDIC? Bailout-related moral hazard issues? Those are hardly “small potatoes.” I get that isn’t “the book they set out to write,” but still I worry that the final picture they present is misleading when it comes to market failure vs. government failure. Adverse selection is really just one part of insurance markets, but this book doesn’t teach you that.

3b. Isn’t excess liability through our court system another major reason why insurance markets fail? We needed a Price-Anderson Act, where government assumes a lot of the liability, to support our nuclear power sector, even though coal alternatives were riskier and more harmful, both short run and long run. In terms of actual importance, hasn’t this been a major, major factor?

3c. Are restrictions on “boil in oil” contracts (no matter what you think of them ethically) another factor in institutional failure here? Maybe that is one way of making America safe for bungee jumping. Or we can follow New Zealand, and limit liability here altogether. The interaction of insurance and liability law is a major issue, and we have not been getting it right.

4. The authors absolutely do consider “positive selection” (e.g., it is the responsible people who buy life insurance, thus leading to a favorable customer pool), but I would give it more emphasis. If you believe that income inequality, “deaths of despair,” and educational polarization are growing problems, this phenomenon likely is becoming more important.

4b. How about more concessions in the Obamacare analysis? For years I read that a weaker mandate would cause the system to collapse. Yet the Republicans significantly cut back on mandate enforcement and the system seems to be getting along OK, at least from that point of view. (In fact, politically speaking Trump arguably saved Obamacare.) What did everyone miss? Did they overrate adverse selection arguments and underrate positive selection? It seems that was a major failing of the economics profession, which if anything was more insistent on “the three legs of the stool” than policymakers were. The authors do cover this all at length, but they can’t bring themselves to note “we got down to 7-8 percent uninsured, the whole thing actually worked out OK, and the economists didn’t quite get it right.”

5. There are plenty of cases when expected “insurance” markets do not exist, and we cannot boil those down to adverse selection. Why don’t all those Bob Shiller proposals happen? (Is it really inside information about gdp? That seems doubtful.) Why aren’t there more prediction markets? Why have so many proposed futures contracts on exchanges failed? These all would seem to serve insurance-like purposes, among their other functions. Yet their supply seems skimpy, at least relative to an economist’s expectations. Why? Perhaps there is more to failed insurance markets than meets the eye.

I know authors can fit only so much into a book, but if I can fit this much into a blog post…I would like to see more! And I think that would result in a more realistic policy balance as well, and draw attention to major issues other than adverse selection.

Wednesday assorted links

1. The end of senior politics in China?

2. A prediction market on prediction market approval.

3. New genetic results on ASD and ADHD overlap.

4. Redux: my 2017 post on Putin and Nord Stream.

5. New Brink Lindsey Substack. And new Sam Hammond Substack.

6. “Contact queuing on the Kazakh border for the second day says that locals have a business where they get two cars in the queue and then let people cut in between them. Selling spots for $500 and can do as many as they want. “So you get why I’ve been here two days,” he says.” Link here.

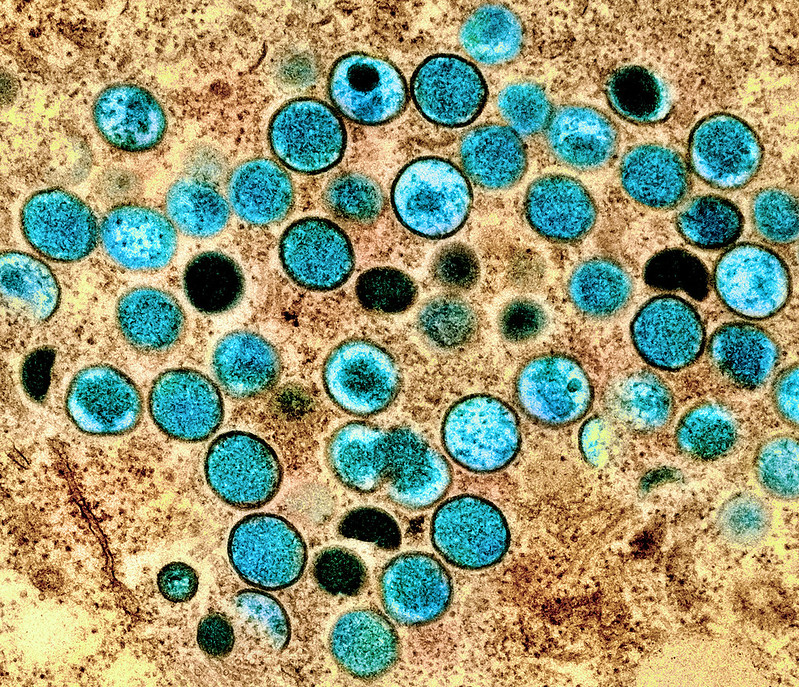

Dose Stretching for the Monkeypox Vaccine

We are making all the same errors with monkeypox policy that we made with Covid but we are correcting the errors more rapidly. (It remains to be seen whether we are correcting rapidly enough.) I’ve already mentioned the rapid movement of some organizations to first doses first for the monkeypox vaccine. Another example is dose stretching. I argued on the basis of immunological evidence that A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective Than a Full Dose of AstraZeneca and with Witold Wiecek, Michael Kremer, Chris Snyder and others wrote a paper simulating the effect of dose stretching for COVID in an SIER model. We even worked with a number of groups to accelerate clinical trials on dose stretching. Yet, the idea was slow to take off. On the other hand, the NIH has already announced a dose stretching trial for monkeypox.

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health are getting ready to explore a possible work-around. They are putting the finishing touches on the design of a clinical trial to assess two methods of stretching available doses of Jynneos, the only vaccine in the United States approved for vaccination against monkeypox.

They plan to test whether fractional dosing — using one-fifth of the regular amount of vaccine per person — would provide as much protection as the current regimen of two full doses of the vaccine given 28 days apart. They will also test whether using a single dose might be enough to protect against infection.

The first approach would allow roughly five times as many people to be vaccinated as the current licensed approach, and the latter would mean twice as many people could be vaccinated with existing vaccine supplies.

…The answers the study will generate, hopefully by late November or early December, could significantly aid efforts to bring this unprecedented monkeypox outbreak under control.

Another interesting aspect of the dose stretching protocol is that the vaccine will be applied to the skin, i.e. intradermally, which is known to often create a stronger immune response. Again, the idea isn’t new, I mentioned it in passing a couple of times on MR. But we just weren’t prepared to take these step for COVID. Nevertheless, COVID got these ideas into the public square and now that the pump has been primed we appear to be moving more rapidly on monkeypox.

Addendum: Jonathan Nankivell asked on the prediction market, Manifold Markets, ‘whether a 1/5 dose of the monkey pox vaccine would provide at least 50% the protection of the full dose?’ which is now running at a 67% chance. Well worth doing the clinical trial! Especially if we think that the supply of the vaccine will not expand soon.