Results for “thomas schelling” 103 found

Assorted links

Should they have let the guy’s house burn down?

David Henderson blogs some of the basic information (Cohn at TNR comments here). Here is the upshot:

He refers to a story about a man who failed to pay an annual fee for fire protection and then, when his house caught on fire and he called the fire department, the fire department refused to show up.

They wouldn't even let him pay up ex post. David notes that this is a government-run fire department and thus the story is not much of a moral reductio on the market. Arguably a private company would behave the same way, sometimes, but it 's odd to claim that government failure reminds you market failure is possible and so let's damn the market. By the way, markets do pretty well at setting up schemes with a penalty for late payment; that's how my mortgage works.

I would make a broader point. Any social system must, at some stage of interactions, impose some morally unacceptable penalties. If you are very hungry, and you shoplift food, they still might prosecute you. If you don't pay your taxes, and resist wage garnishes, they might put you in jail. If you resist arrest, they might, at some point in the chain of events, shoot you while trying to escape. Somewhere along the line there is a doctor who can treat your rare disease except he doesn't feel like working so much, and so he lets you die or suffer; you can find both private and public sector examples here.

Social systems proceed by (usually) covering up the brutalities upon which they are based. The doctor doesn't let you get to his door and then turn you away, rather his home address is hard to find. The government handcuffs you so they don't have to shoot you trying to escape. And so on.

To borrow language from Thomas Schelling, social systems involve costs in terms of both "known" and "statistical" lives. It's the sum total of costs which is important. It's fine (though controversial) to argue that a "known" life should be more important than a "statistical" life, but it's not dispositive to pull out one example of a "known" life and draw a significant conclusion from that anecdote. That's what we teach students not to do in first year principles, sometimes citing Bastiat, the seen and the unseen, and so on.

I don't favor the policies of this fire department, but simply pointing out the vividness one of these social brutalities doesn't much influence me about the broader principles at stake.

A world without nuclear weapons?

Thomas Schelling — who remains a master of cool, insightful analysis, has a new essay on this question. Such a world would not be a picnic. Here is one good excerpt:

In summary, a "world without nuclear weapons" would be a world in which

the United States, Russia, Israel, China, and half a dozen or a dozen

other countries would have hair-trigger mobilization plans to rebuild

nuclear weapons and mobilize or commandeer delivery systems, and would

have prepared targets to preempt other nations' nuclear facilities, all

in a high-alert status, with practice drills and secure emergency

communications. Every crisis would be a nuclear crisis, any war could

become a nuclear war. The urge to preempt would dominate; whoever gets

the first few weapons will coerce or preempt. It would be a nervous

world.

Hat tip goes to www.bookforum.com.

Christmas Game Theory

The lovely wife says the jewelry I bought her for Christmas has to be returned because "it's just too expensive!" Excellent. I get the credit without the credit bill!

What I will never reveal is how far I looked down the game tree before purchase.

Addendum: Do not try this at home. Without extensive knowledge of game theory and your spouse this strategy can be very dangerous to your finances, c.f. Thomas Schelling, brinksmanship.

Assorted links

1. Tim Harford explaining Thomas Schelling.

2. Richard Posner on the financial crisis; a good overview of his new book.

3. Profile of Andrew Sullivan.

4. Lane Kenworthy critique of Goldin and Katz on inequality and education.

Markets in everything: Cupzzas, a pizza baked in cupcake form

"We just really wanted to shatter the cupcake-pizza dichotomy. It’s just existed for too long."

I am a monist myself. Here is much more information. It is also an example of Thomas Schelling’s idea of research by accident:

"[A] lot of our ideas come from just not having the proper materials," Wilder said. "Like the pupzzas came from not being able to find the large tins."

Profile of Malcolm Gladwell and *Outliers*

Ever the optimist, Gladwell’s theories assume the good intentions of

everyone involved. Today, as he watches the world’s financial systems

collapse and people’s life savings go kaput, he radiates calm. Rather

than joining the mobs seeking to hang villainous CEOs from the nearest

lamppost, Gladwell counsels his followers to step back, take a deep

breath, and find the procedural flaw in the system that can be fixed.

“I don’t think anybody was being venal or corrupt. It’s not a scandal

as we normally understand scandals,” he says. “It’s a case of the

system being, the risk models being broken, the system not functioning

as it should, regulation not being appropriate to what people were

doing.” Tinker with the risk models, increase the regulatory structure,

Gladwell says, and the problem is solved. That may not be as

emotionally satisfying as punching out a CEO on a treadmill, but it’s a

lot more comforting.

Here is the whole piece, interesting throughout. Thomas Schelling and Megan McArdle are among those making cameos. Hat tip goes to Andrew Sullivan.

Mad Men

Thomas Schelling showed that it could sometimes pay to be irrational, or at least to appear to be irrational. If they think you’re crazy then in a game of chicken it’s your opponent who will backdown.

It’s known that Nixon understood the theory but in an frightening article in Wired we learn the insane extent to which the theory was practiced.

Frustrated at the state of affairs in Vietnam, Nixon resolved to:

…threaten the Soviet Union with a massive nuclear strike and make its

leaders think he was crazy enough to go through with it. His hope was

that the Soviets would be so frightened of events spinning out of

control that they would strong-arm Hanoi, telling the North Vietnamese

to start making concessions at the negotiating table or risk losing

Soviet military support.

Much more was involved than words, at one point nuclear bombers were sent directly towards Soviet airspace where they triggered the Soviet defense systems.

On the morning of October 27, 1969, a squadron of 18

B-52s – massive bombers with eight turbo engines and 185-foot wingspans

– began racing from the western US toward the eastern border of the

Soviet Union. The pilots flew for 18 hours without rest, hurtling

toward their targets at more than 500 miles per hour. Each plane was

loaded with nuclear weapons hundreds of times more powerful than the

ones that had obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Soviets went nuts but following Nixon’s orders Kissinger told the Soviet ambassador that the President was out of control.

Apparently neither Nixon or Kissinger had absorbed another Schelling insight – if you want to credibly pretend you are out of control then you have to push things so far that sometimes you will be out of control. The number of ways such a plan could have resulted in a nuclear war is truly frightening. After all, Nixon was gambling millions of lives on the Soviets being the rational players in this game.

Next time you are told how a madman threatens the world remember the greatest threats have come from our own mad men.

Logic of Life – Chapter 2: Game Theory isn’t Always about the Games We Play

This review is cross posted on orgtheory.net, the management & social science blog.

It’s a pleasure to be back at the Marginal Revolution. Let me start out by agreeing with Tyler and Bryan. Tim Harford is one of the leading popular social science writers and we’re lucky to have him.

Today, I’ll focus on Chapter Two of Tim’s book, "Las Vegas: The Edge of Reason." In this chapter, Harford describes game theory. In a nutshell, game theory studies any situation where (a) you have multiple people striving to achieve a goal and (b) your actions depend on the actions of the other people in the game. By most accounts, game theory is one of the great accomplishments of modern social science. Once you realize that people’s actions are both utility maximizing and interdependent, then game theory can help you model just about any form of cooperation or conflict.

Harford discusses the basic concepts of game theory with vivid examples ranging from poker, to nuclear war, to quitting smoking. And, as expected, game theory usually provides a great deal of insight. Harford shows how game theory can also be enormously useful, even life saving. Harford recounts how economist Thomas Schelling realized that some situations might encourage participants to jump the gun and initiate devastating conflict. What Schelling realized is that these dangerous games had low information, such as the US misunderstanding a Soviet action, and starting nuclear war. Schelling advocated increased communication between the US and Soviet leadership, including the creation of the hotline between Moscow and the US, which helped defuse tensions in later Cold War disputes.

I’ll finish this post with my one big criticism of game theory, at least the basic version described by Harford and taught in intro courses. In game theory 101, you assume that people develop optimal strategies in response to other rational actors. One huge problem with a lot of these models is that the games are very complicated. It’s hard to imagine most people perform the mental acrobatics of game theory actors.

One response is that game theory is empirically well supported, which suggests that some process drives people to the strategies described by game theory. For example, Harford describes how economists and mathematicians used game theory to sort through the insanely complex game of poker and that the optimal game theory strategy was actually fairly similar to what world class poker players do.

So game theory is supported, right? Not so fast. Game theory has two parts (a) a description of optimal strategies, and (b) a prediction that people will actually solve the game and find these strategies. In my view, game theory 101 is well supported, in poker at least, on point (a), but not (b). In other words, world class poker players rarely sit around and do backwards induction, or any other flavor of equilibrium analysis, but they still obtain strong strategies through trial and error.

What I suspect is that world class poker emerged from an evolutionary process. Very smart people can figure out certain strategies, but nobody can figure out the whole game by themselves, lest they become full time mathematicians. The typical world class poker player probably inherits a bunch of rules that were tested by earlier generations, and adds a few new twists. Competition weeds out bad rules. Even Steve Levitt, star economist, Harvard & MIT grad, developed his own idiosyncratic strategy, rather than solve the game himself.*

In the end, game theory is really a first step in understanding complex interactions. The next step is developing an evolutionary theory of games where actors inherit a tool box of strategies from previous generations of players. Already, there is a fairly well developed genre of game theory taking this approach, but I welcome the day when it becomes refined enough so that it can account not just the strategies of leading poker players, but how these strategies emerged from generations of competition.

*According to the news reports, he developed his own "weird style" rather than completely solve the poker game. But it works for him! What would Johnny von Neumann say?

View quake reading

Ryan Holiday blogs my email to him:

My reading was much different when I was younger. I would more likely

intensively engage with some important book totally full of new ideas.

Hayek. Parfit. Plato. And so on. There just aren’t books like that left

for me anymore. So I read many more, to learn bits, but haven’t in

years experienced a "view quake." That is sad, to me at least, but I

don’t know how to avoid how that has turned out. So enjoy your best

reading years while you can!

Quine should be on that list as well. Nietzsche was a view quake in high school, though I find him oddly uninteresting upon rereading. Here is Ryan’s post on Marcus Aurelius.; the Stoics collectively were a view quake for me, in economics there was Anthony Downs and Thomas Schelling and Albert Hirschmann. David Hume. Maybe Rene Girard was the last "view quake" author I read. On the upside, greater context means that many more books are interesting than was the case before.

Many of you are asking me about Amazon Kindle, the new ebook (sort of); Jason Kottke offers a round-up of opinion.

Roger Myerson, Nobel Laureate

The Nobel Scientific Background paper is the best introduction to all of these people, and a good introduction to mechanism design in general.

As for Myerson, here is his home page. Here is his CV. Here is one overview. Here is Myerson in Google Scholar.

His most cited paper is on auction design. He laid out basic results for how to use auctions to extract revenue and elicit information about the value of the good. These results have informed numerous privatizations and auction schemes in the last twenty-five years.

Here is a very important paper, with David Baron, on how to regulate a monopolist with unknown costs. Strict marginal cost pricing is no longer possible. Under some assumptions, allow the monopolist to charge a relatively high price, but design penalties to elicit an honest reporting of costs. The key point of course is that monopolists won’t always report their costs truthfully. This is one of the most important papers in regulatory economics in the last thirty years and it has helped disillusion many economists with a narrow ideal of marginal cost pricing.

Myerson also has important papers on how social choice theory is linked to bargaining theory, and which social choice procedures are most likely to elicit truthtelling.

I think of his "Mechanism Design with An Informed Principal" as one of his most important papers, though Google Scholar does not concur. Let’s say that a principal knows something an agent does not and wishes to maintain that information asymmetry. How can a principal construct the best incentive scheme for the agent? The problem is, choosing the scheme itself may reveal information to the agent and thus eliminate the principal’s advantage. Myerson showed what solutions to this problem have to look like. This is a very clever problem and a very elegant paper.

Among the current research papers you will notice a strong interest in public choice and institutions, though Myerson is not usually thought of as applied, nor is that where his influence has come. Electoral rules, corruption, and political institutions all are commanding his attention.

Here is an interview with Myerson on game theory. Here is Myerson’s take on the core problems of social choice theory, a summary of the theoretical side of the field.

Here is Myerson on Hurwicz, which is also a very good introduction to Hurwicz.

Off the beaten track, here is Roger Myerson on Thomas Schelling’s Strategy of Conflict. Here is Myerson’s Op-Ed draft on why America should accept limits on its military power, namely to limit deadly rivalries. Here Myerson recommends federalism for Iraq.

Larry Craig

Maybe I spent too much time reading Thomas Schelling (is that possible?), but my main reaction was to wonder how such trade-maximizing conventions get started. I mean the foot tapping, the leaning of the bag against the stall door, and the like. In the early stages of such conventions, I can think of a few paths:

1. Signal something harmless and non-incriminating and hope for reciprocation. Yelling out a clue-laden but non-obscene word or phrase ("Fire Island!") might do the trick. But if the other guy yells back "Berlin!", is that enough to act upon?

2. Signal something costly — incriminating or at least potentially embarrassing — in the hope of establishing your credibility as a social transgressor. Of course you hope to get a costly signal in return. A step-by-step escalation of the signals then follows, so that trust in mutual social deviance is established prior to action. At some point in the escalation the action is worth the risk because the other person is sufficiently out on a limb. As the years pass the escalation of signals proceeds more quickly and cuts out some of the intermediate steps.

3. The initial gains from trade are so high that most participants are willing to run the risk of the blatant signal and the equilibrium is inevitable.

4. High-demanding and reckless "pioneers" establish the convention, by signaling blatantly but against their self-interest. Nonetheless the convention becomes relatively safe once it spreads to many traders.

5. The convention never become so safe (ask Larry Craig) and so we have a separating equilibrium in which only the risk lovers manage to trade in this public environment.

My intuition suggests a mix of #2 and #4 as the most likely paths.

How might you signal your willingness, to a friend, to make fun of or gossip about a common acquaintance?

The Queen

One of the few must-see movies of the year. In addition to its dramatic virtues and superb acting (read Matt’s review), it offers economics, public choice, and political philosophy. The moviemakers appear to understand Thomas Schelling on focal points and convention, "showing that you care" theories of signaling, David Hume on public opinion, and Michael Oakeshott on tradition, among many other ideas.

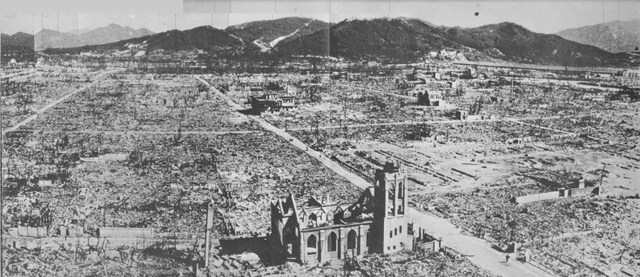

Hiroshima

In case you had forgotten. The Japanese haven’t. Here is the pointer. Here is Thomas Schelling on nuclear weapons. Kim Jong’s favorite movies? "Friday the 13th and Hong Kong action films. He is a big fan of Rambo and James Bond."

Round-up

1. Short list for the Nobel Literature Prize; I am rooting for Orhan Pamuk. Here are Booker Prize odds.

2. TV viewing habits for blacks and whites are converging.

3. How to achieve sustainable gains in happiness: work at happiness-related activities. And maybe winning the lottery helps after all.

4. A journal issue of research inspired by Thomas Schelling.

5. The population of New Orleans is down to 187, 525.