Results for “"minimum wage"” 290 found

Saturday assorted links

1. How to date recordings, using background electrical noise.

2. Visiting Kabul under Taliban rule.

4. Permission-slip culture is hurting America.

5. Old Corpse Road.

6. Amit Varma podcast with Rohini Nilekani.

7. Plastic roads? From the new edition of Works in Progress.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Along at least one dimension, Musk’s Twitter takeover hasn’t mattered much.

2. Which personalities are best suited for training dogs? This is in fact also an excellent essay on who is good at working with ChatGPT. And Chinese views on ChatGPT. And long Stephen Wolfram piece on ChatGPT and neural nets. And top London law firm is hiring a GPT prompt legal engineer.

3. Lina Khan update (WSJ). Ouch. And Joshua Wright on the implications for the FTC, double ouch.

4. Michelin stars make restaurants snobbier.

Public policies as instruction

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Minimum-wage hikes also send the wrong message to voters. Yes, there is literature suggesting that such increases destroy far fewer jobs than previously thought, and may have considerable ancillary benefits, such as preventing suicides. Still, a minimum wage is a kind of price control, and most price controls are bad. Voters may not realize the subtle ways in which minimum-wage hikes are different (and better) from most price controls. Instead, they get the message that the path to higher living standards is through government fiat, rather than better productivity.

If you think that far-fetched, consider the initiative passed by the California Senate this week. The bill would create a government panel to set wages and workplace standards for all fast-food workers in the state, and labor-union backers hope the plan will spread nationally. That may or may not happen, but those are precisely the paths that are opened up by minimum-wage advocacy. Many people hear a bigger and more ambitious message than the one the speaker wishes to send.

So what messages, in the broadest terms, should policies convey? I would like to see increased respect for cosmopolitanism, tolerance, science, just laws, dynamic markets, free speech and the importance of ongoing productivity gains. Obviously any person’s list will depend on his or her values, but for me the educational purposes are more than just a secondary factor. When it comes to prioritizing reforms, the focus should be on those that will “give people the right idea,” so to speak.

The mere fact that you are uncertain about such effects does not mean you can or should ignore them. They are there, whether you like it or not.

Robot Rentals

Economists have long said that r, the interest rate, is the rental rate for capital in the same way that w is the rental rate (wage rate) for labor. Now it’s becoming literally true:

Bloomberg: The robots are coming—and not just to big outfits like automotive or aerospace plants. They’re increasingly popping up in smaller U.S. factories, warehouses, retail stores, farms, and even construction sites.

…a nascent trend of offering robots as a service—similar to the subscription models offered by software makers, wherein customers pay monthly or annual use fees rather than purchasing the products—is opening opportunities to even small companies. That financial model is what led Thomson to embrace automation. The company has robots on 27 of its 89 molding machines and plans to add more. It can’t afford to purchase the robots, which can cost $125,000 each, says Chief Executive Officer Steve Dyer. Instead, Thomson pays for the installed machines by the hour, at a cost that’s less than hiring a human employee—if one could be found, he says. “We just don’t have the margins to generate the kind of capital necessary to go out and make these broad, sweeping investments,” he says. “I’m paying $10 to $12 an hour for a robot that is replacing a position that I was paying $15 to $18 plus fringe benefits.”

…Formic is offering to set up robots and charge as little as $8 an hour, aiming first at the most tedious tasks, such as packing and unpacking products and feeding materials into existing machines. The potential market is huge, and it will only grow as the robots become more sophisticated, Farid says.

Robots will bring manufacturing back to America. A robot workforce should also make human unemployment less volatile because a robot workforce can be increased or shrunk quickly and isn’t worried about nominal wage stickiness. Also, as of yet robots don’t unionize. Robot wages will make the minimum wage more salient. Working out the interactions between a monopsony buyer of labor facing a perfectly elastic supply of robots will be interesting.

Monday assorted links

1. Kevin Kelly lists some heresies.

3. World’s largest cast-iron skillet travels down a Tennessee highway. And the now-deleted thread on Big Tech, work from home, loneliness, Covid, etc.

5. The variability and volatility of sleep.

6. More Chris Blattman non-fiction recommendations.

7. “Even according to exaggerated figures, China’s total fertility rate in 2021 was only 1.1-1.2, far below the 1.8 forecast by Chinese State Council in 2016, the 1.6-1.7 forecast by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2019, the 1.7 forecast by UN in 2019” Link here.

Monday assorted links

A Nobel Prize for the Credibility Revolution

The Nobel Prize goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. If you seek their monuments look around you. Almost all of the empirical work in economics that you read in the popular press (and plenty that doesn’t make the popular press) is due to analyzing natural experiments using techniques such as difference in differences, instrumental variables and regression discontinuity. The techniques are powerful but the ideas behind them are also understandable by the person in the street which has given economists a tremendous advantage when talking with the public. Take, for example, the famous minimum wage study of Card and Krueger (1994) (and here). The study is well known because of its paradoxical finding that New Jersey’s increase in the minimum wage in 1992 didn’t reduce employment at fast food restaurants and may even have increased employment. But what really made the paper great was the clarity of the methods that Card and Krueger used to study the problem.

The obvious way to estimate the effect of the minimum wage is to look at the difference in employment in fast food restaurants before and after the law went into effect. But other things are changing through time so circa 1992 the standard approach was to “control for” other variables by also including in the statistical analysis factors such as the state of the economy. Include enough control variables, so the reasoning went, and you would uncover the true effect of the minimum wage. Card and Krueger did something different, they turned to a control group.

Pennsylvania didn’t pass a minimum wage law in 1992 but it’s close to New Jersey so Card and Kruger reasoned that whatever other factors were affecting New Jersey fast food restaurants would very likely also influence Pennsylvania fast food restaurants. The state of the economy, for example, would likely have a similar effect on demand for fast food in NJ as in PA as would say the weather. In fact, the argument extends to just about any other factor that one might imagine including demographics, changes in tastes and changes in supply costs. The standard approach circa 1992 of “controlling for” other variables requires, at the very least, that we know what other variables are important. But by using a control group, we don’t need to know what the other variables are only that whatever they are they are likely to influence NJ and PA fast food restaurants similarly. Put differently NJ and PA are similar so what happened in PA is a good estimate of what would have happened in NJ had NJ not passed the minimum wage.

Thus Card and Kruger estimated the effect of the minimum wage in New Jersey by calculating the difference in employment in NJ before and after the law and then subtracting the difference in employment in PA before and after the law. Hence the term difference in differences. By subtracting the PA difference (i.e. what would have happened in NJ if the law had not been passed) from the NJ difference (what actually happened) we are left with the effect of the minimum wage. Brilliant!

Yet by today’s standards, obvious! Indeed, it’s hard to understand that circa 1992 the idea of differences in differences was not common. Despite the fact that differences in differences was actually pioneered by the physician John Snow in his identification of the causes of cholera in the 1840 and 1850s! What seems obvious today was not so obvious to generations of economists who used other, less credible, techniques even when there was no technical barrier to using better methods.

Furthermore, it’s less appreciated but not less important that Card and Krueger went beyond the NJ-PA comparison. Maybe PA isn’t a good control for NJ. Ok, let’s try another control. Some fast food restaurants in NJ were paying more than the minimum wage even before the minimum wage went into effect. Since these restaurants were always paying more than the minimum wage the minimum wage law shouldn’t influence employment at these restaurants. But these high-wage fast-food restaurants should be influenced by other factors influencing the demand for and cost of fast food such as the state of the economy, input prices, demographics and so forth. Thus, Card and Krueger also calculated the effect of the minimum wage by subtracting the difference in employment in high wage restaurants (uninfluenced by the law) from the difference in employment in low-wage restaurants. Their results were similar to the NJ-PA comparison.

The importance of Card and Krueger (1994) was not the result (which continue to be debated) but that Card and Krueger revealed to economists that there were natural experiments with plausible treatment and control groups all around us, if only we had the creativity to see them. The last thirty years of empirical economics has been the result of economists opening their eyes to the natural experiments all around them.

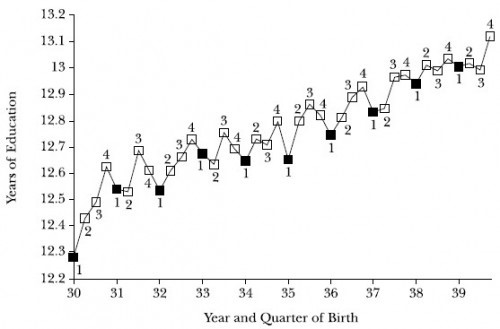

Angrist and Krueger’s (1991) paper Does Compulsory School Attendance Affect Schooling and Earnings? Is one of the most beautiful in all of economics. It begins with a seemingly absurd strategy and yet in the light of a few pictures it convinces the reader that the strategy isn’t absurd but brilliant.

The problem is a classic one, how to estimate the effect of schooling on earnings? People with more schooling earn more but is this because of the schooling or is it because people who get more schooling have more ability? Angrist and Krueger’s strategy is to use the correlation between a student’s quarter of birth and their years of education to estimate the effect of schooling on earnings. What?! What could a student’s quarter of birth possibly have to do with how much education a student receives? Is this some weird kind of economic astrology?

Angrist and Krueger exploit two quirks of US education. The first quirk is that a child born in late December can start first grade earlier than a child, nearly the same age, who is born in early January. The second quirk is that for many decades an individual could quit school at age 16. Put these two quirks together and what you get is that people born in the fourth quarter are a little bit more likely to have a little bit more education than similar students born in the first quarter. Scott Cunningham’s excellent textbook on causal inference, The Mixtape, has a nice diagram:

Putting it all together what this means is that the random factor of quarter of birth is correlated with (months) of education. Who would think of such a thing? Not me. I’d scoff that you could pick up such a small effect in the data. But here come the pictures! Picture One (from a review paper, Angrist and Krueger 2001) shows quarter of birth and total education. What you see is that years of education are going up over time as it becomes more common for everyone to stay in school beyond age 16. But notice the saw tooth pattern. People who were born in the first quarter of the year get a little bit less education than people born in the fourth quarter! The difference is small, .1 or so of a year but it’s clear the difference is there.

Ok, now for the payoff. Since quarter of birth is random it’s as if someone randomly assigned some students to get more education than other students—thus Angrist and Krueger are uncovering a random experiment in natural data. The next step then is to look and see how earnings vary with quarter of birth. Here’s the picture.

Crazy! But there it is plain as day. People who were born in the first quarter have slightly less education than people born in the fourth quarter (figure one) and people born in the first quarter have slightly lower earnings than people born in the fourth quarter (figure two). The effect on earnings is small, about 1%, but recall that quarter of birth only changes education by about .1 of a year so dividing the former by the latter gives an estimate that implies an extra year of education increases earnings by a healthy 10%.

Lots more could be said here. Can we be sure that quarter of birth is random? It seems random but other researchers have found correlations between quarter of birth and schizophrenia, autism and IQ perhaps due to sunlight or food-availability effects. These effects are very small but remember so is the influence of quarter of birth on earnings so a small effect can still bias the results. Is quarter of birth as random as a random number generator? Maybe not! Such is the progress of science.

As with Card and Kruger the innovation in this paper was not the result but the method. Open your eyes, be creative, uncover the natural experiments that abound–this was the lesson of the credibility revolution.

Guido Imbens of Stanford (grew up in the Netherlands) has been less involved in clever studies of empirical phenomena but rather in developing the theoretical framework. The key papers are Angrist and Imbens (1994), Identification and Estimation of Local Treatment Effects and Angrist, Imbens and Rubin, Identification of Causal Effects Using Instrumental Variables which answers the question: When we use an instrumental variable what exactly is it that we are measuring? In a study of the flu, for example, some doctors were randomly reminded/encouraged to offer their patients the flu shot. We can use the randomization as an instrumental variable to measure the effect of the flu shot. But note, some patients will always get a flu shot (say the elderly). Some patients will never get a flu shot (say the young). So what we are really measuring is not the effect of the flu shot on everyone (the average treatment effect) but rather on the subset of patients who got the flu shot because their doctor was encouraged–that latter effect is known as the local average treatment effect. It’s the treatment effect for those who are influenced by the instrument (the random encouragement) which is not necessarily the same as the effect of the flu shot on groups of people who were not influenced by the instrument.

By the way, Imbens is married to Susan Athey, herself a potential Nobel Prize winner. Imbens-Athey have many joint papers bringing causal inference and machine learning together. The Akerlof-Yellen of the new generation. Talk about assortative matching. Angrist, by the way, was the best man at the wedding!

A very worthy trio.

David Card on the return to schooling

Card is best known amongst intellectuals for his minimum wage work, but he also has been central in estimating the returns to higher education, using superior methods. In particular, he has induced many economists to downgrade the import of the signaling model of education. Here is one excerpt from his Econometrica paper, appropriately entitled “Estimating the Return to Schooling: Progress on Some Persistent Econometric Problems:

A review of studies that have used compulsory schooling laws, differences in the accessibility of schools, and similar features as instrumental variables for completed education, reveals that the resulting estimates of the return to schooling are typically as

big or bigger than the corresponding ordinary least squares estimates. One interpretation of this finding is that marginal returns to education among the low-education subgroups typically affected by supply-side innovations tend to be relatively high, reflecting their high marginal costs of schooling, rather than low ability that limits their return to education.

The empirical problem arises of course because intrinsic talent and degree of schooling are highly correlated, so the investigator needs some recourse to superior identification. How can you tell if apparent returns to schooling simply reflect a higher talented cohort in the first place? So you might for instance look for an exogenous change to compulsory schooling laws that affects some children but not others (a few of those have come in the Nordic countries). That likely will be uncorrelated with child talent, and so it will help you separate out the true causal return to additional schooling, because you can measure whether the kids with that extra year end up earning more, controlling for other relevant variables of course. And see Alex’s discussion of the Angrist and Card paper on similar questions.

See also Card’s survey of this entire field, written for Handbook of Labor Economics. One impressive feature of these pieces is they show how many disparate methods of measurement all point toward a broadly common conclusion. Whether or not you agree, these papers have been extremely influential, and they are one reason why Claudia Goldin, in my recent CWT with her, asserted that very little of higher education was about the signaling premium.

Monday assorted links

1. Deportees.

3. “James, what inspired you to put your vaccination record on your T-shirt?”

4. Ezra Klein on the supply side (NYT).

5. “Academic freedom no longer includes freedom to be a generalist.” (NYT)

6. Sexual harassment is reported more selectively during recessions.

7. And sanity about the minimum wage. The Jeffrey P. Clemens tweet storm is useful as a summary. Theory and empirics are reunited, and no it ain’t monopsony (as if you didn’t know that already).

What should be taught more in the first-year graduate sequence in economics?

Or maybe just taught more period? For microeconomics, I have two very definite picks:

1. Price discrimination. They do it to you more and more! Or perhaps you are striving to do it to others. This is typically covered in a first-year sequence, but how many second-year students really have mastered when it is welfare-improving or not? How it relates to product tying? When it is sustainable against entry or not?

This seems like a highly relevant real world topic covered only in passing, noting that at the Principles level Cowen and Tabarrok give it full attention.

2. Tax incidence. Covered thoroughly in public finance sequences, but usually only in passing in first-year sequences. But just about everything is a problem in tax incidence! Any change in relative prices gives rise to tax incidence issues, and aren’t relative price changes central to economics?

How can you analyze minimum wage economics, for instance, without a strong background in tax incidence theory (and empirics)? What if someone says “that minimum wage hike — the associated gains are just captured by the landlords!” Right or wrong? Under what conditions? Good luck!

Grad students these days aren’t learning enough micro theory.

And for macroeconomics? I have a definite nomination:

3. Say’s Law. Yes I have read Keynes, and furthermore John Stuart Mill understood as early as 1829 that Say’s Law doesn’t hold if there is a big increase in money hoardings. But often there isn’t a big increase in money hoardings! And then what people call “increases in aggregate demand” very often are more fundamentally “increases in aggregate supply.” Long-, medium- and short-term considerations to be tossed in as further complexities. Ngdp boosts can come through either nominal or real variables, etc.

There are still lots and lots of people — at all levels — who don’t have a firm handle on these matters. And Twitter has made this worse.

Which topics do you think should be given additional coverage?

Book Review: Andy Slavitt’s Preventable

Like Michael Lewis’s The Premonition which I reviewed earlier, Andy Slavitt’s Preventable is a story of heroes, only all the heroes are named Andy Slavitt. It begins, as all such stories do, with an urgent call from the White House…the President needs you now! When not reminding us (e.g. xv, 14, 105, 112, 133, 242, 249) of how he did “nearly the impossible” and saved Obamacare he tells us how grateful other people were for his wise counsel, e.g. “Jared Kushner’s name again flashed on my phone. I picked up, and he was polite and appreciative of my past help.” (p.113), “John Doer was right to challenge me to make my concerns known publicly. Hundreds of thousands of people were following my tweets…” (p. 55)

Slavitt deserves praise for his work during the pandemic so I shouldn’t be so churlish but Preventable is shallow and politicized and it rubbed me the wrong way. Instead of an “inside account” we get little more than a day-by-day account familiar to anyone who lived through the last year and half. Slavitt rarely departs from the standard narrative.

Trump, of course, comes in for plenty of criticism for his mishandling of the crisis. Perhaps the most telling episode was when an infected Trump demanded a publicity jaunt in a hermetically sealed car with Secret Service personnel. Trump didn’t care enough to protect those who protected him. No surprise he didn’t protect us.

The standard narrative, however, leads Slavitt to make blanket assertions—the kind that everyone of a certain type knows to be true–but in fact are false. He writes, for example:

In comparison to most of these other countries, the American public was impatient, untrusting, and unaccustomed to sacrificing individual rights for the public good. (p. 65)

Data from the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) show that the US “sacrifice” as measured by the stringency of the COVID policy response–school closures; workplace closures; restrictions on public gatherings; restrictions on internal movements; mask requirements; testing requirements and so forth–was well within the European and Canadian average.

The pandemic and the lockdowns split Americans from their friends and families. Birthdays, anniversaries, even funerals were relegated to Zoom. Jobs and businesses were lost in the millions. Children couldn’t see their friends or even play in the park. Churches and bars were shuttered. Music was silenced. Americans sacrificed plenty.

Some of Slavitt’s assertions are absurd.

The U.S. response to the pandemic differed from the response in other parts of the world largely in the degree to which the government was reluctant to interfere with our system of laissez-faire capitalism…

Laissez-faire capitalism??! Political hyperbole paired with lazy writing. It would be laughable except for the fact that such hyperbole biases our thinking. If you read Slavitt uncritically you’d assume–as Slavitt does–that when the pandemic hit, US workers were cast aside to fend for themselves. In fact, the US fiscal response to the pandemic was among the largest and most generous in the world. An unemployed minimum wage worker in the United States, for example, was paid a much larger share of their income during the pandemic than a similar worker in Canada, France, or Germany (and no, that wasn’t because the US replacement rate was low to begin with.)

This is not to deny that low-wage workers bore a larger brunt of the pandemic than high-wage workers, many of whom could work from home. Slavitt implies, however, that this was a “room-service pandemic” in which the high-wage workers demanded a reopening of the economy at the expense of low-wage workers. As far as the data indicate, however, the big divisions of opinion were political and tribal not by income per se. The Washington Post, for example, concluded:

There was no significant difference in the percentage of people who said social distancing measures were worth the cost between those who’d seen no economic impact and those who said the impacts were a major problem for their households. Both groups broadly support the measures.

Perhaps because Slavitt believes his own hyperbole about a laissez-faire economy he can’t quite bring himself to say that Operation Warp Speed, a big government program of early investment to accelerate vaccines, was a tremendous success. Instead he winds up complaining that “even with $1 billion worth of funding for research and development, Moderna ended up selling its vaccine at about twice the cost of an influenza vaccine.” (p. 190). Can you believe it? A life-saving, economy-boosting, pandemic ending, incredibly-cheap vaccine, cost twice as much as the flu vaccine! The horror.

Slavitt’s narrative lines up “scientific experts” against “deniers, fauxers, and herders” with the scientific experts united on the pro-lockdown side. Let’s consider. In Europe one country above all others followed the Slavitt ideal of an expert-led pandemic response. A country where the public health authority was free from interference from politicians. A country where the public had tremendous trust in the state. A country where the public were committed to collective solidarity and the public welfare. That country, of course, was Sweden. Yet in Sweden the highly regarded Public Health Agency, led by state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, an expert in infectious diseases who had directed Sweden’s response to the swine flu epidemic, opposed lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the general use of masks.

Moreover, the Public Health Agency of Sweden and Tegnell weren’t a bizarre anomaly, anti-lockdown was probably the dominant expert position prior to COVID. In a 2006 review of pandemic policy, for example, four highly-regarded experts argued:

It is difficult to identify circumstances in the past half-century when large-scale quarantine has been effectively used in the control of any disease. The negative consequences of large-scale quarantine are so extreme (forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.

Travel restrictions, such as closing airports and screening travelers at borders, have historically been ineffective.

….a policy calling for communitywide cancellation of public events seems inadvisable.

The authors included Thomas V. Inglesby, the Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, one of the most highly respected centers for infectious diseases in the world, and D.A. Henderson, the legendary epidemiologist widely credited with eliminating smallpox from the planet.

Tegnell argued that “if other countries were led by experts rather than politicians, more nations would have policies like Sweden’s” and he may have been right. In the United States, for example, the Great Barrington declaration, which argued for a Swedish style approach and which Slavitt denounces in lurid and slanderous terms, was written by three highly-qualified, expert epidemiologists; Martin Kulldorff from Harvard, Sunetra Gupta from Oxford and Jay Bhattacharya from Stanford. One would be hard-pressed to find a more expert group.

The point is not that we should have followed the Great Barrington experts (for what it is worth, I opposed the Great Barrington declaration). Ecclesiastes tells us:

… that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

In other words, the experts can be wrong. Indeed, the experts are often divided, so many of them must be wrong. The experts also often base their policy recommendations on factors beyond their expertise, including educational, class, and ideological biases, so the experts are to be trusted more on factual questions than on ethical answers. Nevertheless, the experts are more likely to be right than the non-experts. So how should one navigate these nuances in a democratic society? Slavitt doesn’t say.

Slavitt’s simple narrative–Trump bad, Biden good, Follow the Science, Be Kind–can’t help us as we try to improve future policy. Slavitt ignores most of the big questions. Why did the CDC fail in its primary mission? Indeed, why did the CDC often slow our response? Why did the NIH not quickly fund COVID research giving us better insight on the virus and its spread? Why were the states so moribund and listless? Why did the United States fail to adopt first doses first, even though that policy successfully saved lives by speeding up vaccinations in Great Britain and Canada?

To the extent that Slavitt does offer policy recommendations they aren’t about reforming the CDC, FDA or NIH. Instead he offers us a tired laundry list; a living wage, affordable housing, voting reform, lobbying reform, national broadband, and reduction of income inequality. Surprise! The pandemic justified everything you believed all along! But many countries with these reforms performed poorly during the pandemic and many without, such as authoritarian China, performed relatively well. All good things do not correlate.

Trump’s mishandling of the pandemic make it easy to blame him and call it a day. But the rot is deep. If we do not get to the core of our problems we will not be ready for the next emergency. If we are lucky, we might face the next emergency with better leadership but a great country does not rely on luck.

Monday assorted links

2. More on the new CRISPR/mRNA results.

3. It ain’t monopsony: incidence of minimum wage hikes in Los Angeles.

4. Fredric Rzewski, RIP (NYT).

“Why economics is failing us”

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Here’s the dirty little secret that few of my fellow economics professors will admit: As those “perfect” research papers have grown longer, they have also become less relevant. Fewer people — including academics — read them carefully or are influenced by them when it comes to policy.

Actual views on politics are more influenced by debates on social media, especially on such hot topics such as the minimum wage or monetary and fiscal policy. The growing role of Twitter doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Social media is egalitarian, spurs spirited debate and enables research cooperation across great distances.

Still, an earlier culture of “debate through books” has been replaced by a new culture of “debate through tweets.” This is not necessarily progress.

To use a bit of economic terminology, economists haven’t fully internalized the lessons of the Laffer Curve. By demanding so much rigor in academic research, they’ve created an environment in which most of the economics people actually see is less rigorous.

There is also a political effect. Twitter is a relatively left-wing social medium, and so the tenor of popular economic discourse has moved to the left.

Recommended, and it is one of those pieces where the reaction to the piece itself confirms the thesis of the piece…

Thursday assorted links

1.”Thomas Bagger, German diplomat and advisor to the federal president, once noted, “The end of history was an American idea, but it was a German reality.” Link here.

2. For all the mockery, we are almost at Dow 36,000.

4. “Using event study analysis of recent minimum wage increases, we find that these changes do not affect the likelihood of searching, but do lead to large yet very transitory spikes in search effort by individuals already looking for work.” Link here.

And Slocum chimes in:

Here is the link to the comments.