Results for “dylan” 123 found

Assorted links

1. After the food court closes.

2. Thursday night, a dialogue between me and Megan McArdle about her new book.

3. How to build truly cheap housing for the poor.

4. Rafael Yglesias on…a bunch of stuff, including Woody Allen. And how will authors (but not Rafael) respond to the demand for binge reading?

6. There is no Japanese great stagnation. And buy shares in a football player.

How much does social mobility ever change?

Here is Dylan Matthews interviewing Gregory Clark about his new book The Son also Rises:

Another remarkable feature of the surname data is how seemingly impervious social mobility rates are to government interventions. In all societies, what seems to matter is just who your parents are. At the extreme, we see in modern Sweden an extensive system of public education and social support. Yet underlying mobility rates are no higher in modern Sweden than in pre-industrial Sweden or medieval England.

There was one case where government interventions did seem to promote mobility, which was in Bengal, in India. There the strict quota system in educational institutions had benefited significantly people with surnames associated with the Scheduled Castes.

But the bizarre element here is that these quotas did not help those truly at the bottom of the social ladder. Instead, the benefits went to families of average social status whom the British had mistakenly classified as Scheduled Caste. These families have now become a new elite. The truly disadvantaged, such as the large Muslim community, have been correspondingly further burdened by being excluded from these quotas.

Interestingly, in China, the extreme social intervention represented by the Communist Revolution of 1949, which included executing large numbers of members of the old upper class, has not resulted in much of an increase in social mobility. Surnames of high status in the Imperial and Republican era continue to be overrepresented among modern elites, including Communist Party officials.

The families that have high social competence, whatever the social system is, typically find their way to the top of the social ladder.

The interview is interesting throughout. And you will of course note the new Chetty results — created with entirely different methods and data — showing economic mobility has not much changed in the United States for decades.

For the initial pointer I thank Samir Varma.

The new Ezra Klein venture at Vox

You can find Ezra’s words here. Do read the whole thing, here is one excerpt:

Today, we are better than ever at telling people what’s happening, but not nearly good enough at giving them the crucial contextual information necessary to understand what’s happened. We treat the emphasis on the newness of information as an important virtue rather than a painful compromise.

The news business, however, is just a subset of the informing-our-audience business — and that’s the business we aim to be in. Our mission is to create a site that’s as good at explaining the world as it is at reporting on it.

Matt Yglesias, Dylan Matthews, and Melissa Bell (and others to follow) will be coming along. Here is David Carr on the venture.

Addendum: The jobs ad is quite useful:

Project X (working title) is a user’s guide to the news produced by the beat reporters and subject area experts who know it best.

We’ll have regular coverage of everything from tax policy to True Detective, but instead of letting that reporting gather dust in an archive, we’ll use it to build and continuously update a comprehensive set of explainers of the topics we cover. We want to create the single best resources for news consumers anywhere.

We’ll need writers who are obsessively knowledgeable about their subjects to do that reporting and write those explainers — as well as ambitious feature pieces. We’ll need D3 hackers and other data viz geniuses who can explain the news in ways words can’t. We’ll need video producers who can make a two-minute cartoon that summarizes the Volcker rule perfectly. We’ll need coders and designers who can build the world’s first hybrid news site/encyclopedia. And we’ll need people who want to join Vox’s great creative team because they believe in making ads so beautiful that our readers actually come back for them too.

Sound like you? Then apply now.

And Ezra explains more here.

Can we sell a good undergraduate degree for $10,000?

Dylan Matthews has an interesting discussion of a plan by Anya Kamenetz, you can read an outline of the plan here. The upshot of her approach is that an entire degree can be done for 10k per student. There is much in the plan I have sympathy for, and I do think higher education could be much cheaper and still serve most of its useful functions. That said, I consider this specific proposal to involve some overselling.

Let me just pick up on the single sub-proposal closest to my life:

She [Kamenetz] would also abolish the major of “business,” the single most popular undergraduate major, but perhaps also the least rigorous, and which produces relatively poor-achieving students. Instead, she’d fold practical business classes into the economics major.

Let’s just, for the sake of argument, accept the premise of the business major being less rigorous at many schools. I would not make such an incendiary claim myself, certainly not about my own school, but this is an exercise in logic, not empirics.

OK, so at many schools below the top, what would happen? It would be simple: many of the former or would-have-been business majors would not be able to pass the mid- or upper-level classes of the economics major. What then?

You can flunk out the less scholastically oriented business majors, which is probably not a good idea.

Or you could make all of those economics classes much easier, which is also probably not a good idea. The better students lose out and the whole major becomes worth less money and also less prestigious for the school. In essence you end up abolishing the economics major.

Or you can push the former business majors into some other easy major (communications? education?…those are againt purely hypothetical examples, please put aside the empirics). That’s not the end of the world, but then the point of the exercise is less than clear. If a lot of students want to be business majors, is it such a big educational gain to shovel them into some major they perhaps do not want and may also be less marketable?

The most likely outcome would be the creation of a multi-tiered economics major, with a harder track and easier track, labeled accordingly, a bit like the B.S. vs. the B.A., though different in the details. Again, that is hardly the end of the world, and maybe the idea is worth considering, but at this point we must again ask where are the gains. I have an idea: let’s call the less rigorous economics track the business major. Or in the interests of the fig leaf producers, how about the business economics major? The reality is that many schools do combine economics and business and they don’t seem to achieve major competitive or cost advantages in doing so; in fact they may be more likely to encounter clashes of mission and disagreements over what kind of faculty to hire.

(Are there big gains in overhead reduction from consolidating these two departments? I don’t see it. And note that some business schools which contain economics departments are broken down into “groups,” sometimes with semi-autonomous status to limit conflict and transactions costs, and that is going to bring back some overhead costs.)

And so on. Many parts of such proposals cannot be readily translated into reality, at least not a reality where the cost of a four-year degree sinks to 10k total. A big problem with a lot of “good ideas” for education is simply that (in various hypothetical universes) the students are not up to them.

The nature of current unemployment

Dylan Matthews writes:

…Short-term unemployment is actually lower than it was in 2007. Indeed, the percentage of the labor force that had been unemployed for five weeks or less didn’t grow all that much during the economic meltdown. What changed was what happened after or within those five weeks. In 2007, they typically ended with a job. In 2009 and 2010, they more often ended with another few weeks of unemployment. The result is that if you break down the unemployment rate by duration, the problem appears to be almost entirely about long-term unemployment…

There is more here, including a good picture.

Assorted links

1. Blog of a funeral director; “Death keeps no schedule and neither will you.” And here are “Ten Reasons to be a Funeral Director.”

2. The real traveling salesman problem.

3. Insider trading for the literary Nobel Prize?

5. Ten-part Dylan Matthews Wonkbook series on why the tuition is so high.

6. Which new bet did Ehrlich propose to Julian Simon, which Simon did not accept?

7. Miles Kimball on negative interest rates.

My favorite things Minnesota

I am here for but a short time, speaking at the university, but here is what comes to mind:

1. Folk singer: Is that what he is? Bringing it All Back Home remains my favorite Dylan album, of many candidates.

2. Rock music: The Replacements were pretty awesome for a short while. The Artist Formerly Known as Prince has an impressive body of work, with Sign of the Times as my favorite or maybe Dirty Mind, though when viewed as a whole I find the corpus of work rather numbing and even somewhat off-putting. Bob Mould I like but do not love, the peaks are too low.

3. Jazz: The Bad Plus come to mind.

4. Writer: Must I go with F. Scott Fitzgerald? I don’t like his work very much, so Ole Rolvaag is my choice.

5. Coen Brothers movie: Raising Arizona or Fargo. The more serious ones strike me as too grim.

6. Director: George Roy Hill, how about A Little Romance?

7. Columnist: The underrated Thomas Friedman, who ought to be considered one of the world’s leading conservative columnists but is not.

8. Scientist: Norman Borlaug. I hope you all know who he is by now.

9. Advice columnist: Ann Landers, most of the time she was right, much better and sharper than her sister Dear Abby, plus she coined better phrases.

What else? Garrison Keillor belongs somewhere, even though he isn’t funny. Thorstein Veblen is often unreadable but on status competition, and its Darwinian roots, he was way ahead of his time.

Overall this is a very strong state, and on top of that I feel I am missing some significant contributors with this list. Are there painters or sculptors of note from Minnesota? I can’t think of any.

Where should Edward Snowden go?

Assuming he can get there, of course. Currently it’s down to Venezuela, Bolivia, or Nicaragua. Dylan Matthews argues for Venezuela, on the grounds that the other two countries are much poorer and have lower life expectancies. He says Snowden should put up with the much higher crime rate (by the way “0.2 percent of Caracas residents [are] killed each year.”)

But Snowden is not playing a Rawlsian game here, he is going to these countries as Edward Snowden. I say seek out Santa Cruz, Bolivia, which is much richer than Bolivia as a whole and safer than Venezuela at least. Sloths hang from the trees. Also keep in mind that much of Snowden’s income may be coming from abroad, whether it be from Wikileaks or book royalties or civil libertarian well-wishers or sources unknown. That militates in favor of the cheaper, lower wage country and Bolivia fits the bill. Nicaragua is quite nice, and attracts some notable expats (pdf), but if you can’t travel abroad choose a larger country.

Finally, Venezuela has had some pro-American tendencies in its history and those could return. Bolivia seems to have a more or less stable indigenous (semi) democratic majority, plus the hijacking of Morales’s plane may give the Snowden issue a resonance in Bolivia for some time to come.

If he loves the beach, however, Leon, Nicaragua is a charming town.

*Confessions of a Sociopath*

I suspect nothing in this book can be trusted. Still, it is one of the more stimulating reads of the year, though I have to be careful not to draw serious inferences from it. Does its possible fictionality make it easier to create so many interesting passages?:

I can seem amazingly prescient and insightful, to the point that people proclaim that no one else has ever understood them as well as I do. But the truth is far more complex and hinges on the meaning of understanding. In a way, I don’t understand them at all. I can only make predictions based on the past behavior they’ve exhibited to me, the same way computers determine whether you’re a bad credit risk based on millions of data points. I am the ultimate empiricist, and not by choice.

The author argues that sociopaths are often very smart, have a lot of natural cognitive advantages in manipulating data, and are frequently sought out as friends for their ability to appeal to others. It is claimed that, ceteris paribus, we will stick with the sociopath buddies, as we are quite ready to use sociopaths to suit our own ends, justly or not. It is claimed that for all of their flaws, many but not all sociopaths are capable of understanding what is in essence the contractarian case for being moral — rational self-interest — and sticking with it. Citing some research in the area (pdf), the author speculates that sociopaths may have an “attention bottleneck,” so they do not receive the cognitive emotional and moral feedback which others do, unless they decide very consciously to focus on a potential emotion. For sociopaths, top down processing of emotions is not automatic.

We even learn that (supposedly) sociopaths are often infovores. It seems many but not all sociopaths are relatively conscientious, and the author of this book (supposedly) teaches Sunday school and tithes ten percent to the church. It just so happens sociopaths sometimes think about killing or destroying other people, without feeling much in the way of remorse.

I can also recommend this book as an absorbing memoir of a law professor and also of a Mormon outlier. It is written at a high level of intelligence, and it details how to get good legal teaching evaluations, how to please colleagues, how to evade Mormon proscriptions on sex before marriage, and it offers an interesting hypothesis as to why sociopaths tend to be more sexually flexible than the average person (hint: think more systematically about what abnormal or weakened top-down processing of emotions might mean in other spheres of life).

The author argues that sociopaths can do what two generations of econometricians have only barely managed, namely to defeat the efficient markets hypothesis and earn systematically super-normal returns. What does it say about me that I find this the least plausible claim in the entire book?

Here is a useful New York Times review. Here is the author’s blog, which is about being a sociopath, or about pretending to be a sociopath, or perhaps both. Here is the book on Amazon and note how many readers hated it. I say they just don’t like sociopaths.

One hypothesis is that this book is a stunt, designed as an experiment in one’s ability to erase or conceal an on-line identity, although I would think a major publisher (Crown) is not up for such tricks these days. An alternative is that a sociopath — not the one portrayed in the book — is trying to frame an innocent person as the author of the book (some trackable identity clues are left), noting that the book itself discusses at length plans to destroy others for various (non-justified) reasons. Or is it a Straussian critique of the Mormon Church for (supposedly) encouraging sociopathic-related character traits in its non-sociopath members? Or all of the above?

You will note that the book’s opening diagnosis comes from an actual clinical psychologist in the area, and the Crown legal department would have no interest in misrepresenting him in this manner. So the default hypothesis has to be that this book represents some version of the truth, at least as seen through the author’s eyes.

Some version of the author, wearing a blonde wig it seems, appeared on the Dr. Phil show, to the scorn of Phil I might add.

I cannot evaluate the scientific claims in this book, and would I trust the literature on sociopaths anyway, given that the author claims it is subject to the severe selection bias of having more access to the sociopathic losers and criminals? (I buy this argument, by the way.) It did occur to me however, that for the rehabilitation of sociopaths, whether through books or other means, perhaps they should consider…a rebranding exercise? But wait, “Sorry, I could not find synonyms for ‘sociopath’.”

If nothing else, this book will wake you up as to how little you (probably) know about sociopaths.

Partisan Bias Diminishes When Partisans Pay

In November of last year I wrote:

Overall, I am for betting because I am against bullshit. Bullshit is polluting our discourse and drowning the facts. A bet costs the bullshitter more than the non-bullshitter so the willingness to bet signals honest belief. A bet is a tax on bullshit; and it is a just tax, tribute paid by the bullshitters to those with genuine knowledge.

A recent paper provides evidence. It’s well known that Democrats and Republicans give different answers to even basic factual questions when those questions are politically loaded (Did inflation fall under Reagan? Were WMDs found in Iraq? and so forth). But do the respondents really believe their answers or are they simply signalling their affiliations? In other words, are respondents bullshitting? In a new paper, Bullock, Gerber, Huber and Hill provide evidence that the respondents don’t actually believe what they say and the authors do so by making partisans pay for their beliefs. Dylan Matthews at Wonkblog has a good writeup:

They ran two experiments. In the first, they split respondents into two groups: Those in the control group were asked basic factual questions about politics; those in the treatment group were asked the same questions but were entered into a raffle for an Amazon gift card wherein their chances depended on how many questions they got right.

In the control group, the authors find what Bartels, Nyhan and Reifler found: There are big partisan gaps in the accuracy of responses.

…But when there was money on the line, the size of the gaps shrank by 55 percent. The researchers ran another experiment, in which they increased the odds of winning for those who answered the questions correctly but also offered a smaller reward to those who answered “don’t know” rather than answering falsely. The partisan gaps narrowed by 80 percent.

The paper also has implications for democracy. Voting is just another survey without individual consequence so voting encourages expressions of rational irrationality and it’s no surprise why democracies choose bad policies.

Hat tip: @jneeley78.

How to save the world — earn more and give it away

Dylan Matthews reports:

Jason Trigg went into finance because he is after money — as much as he can earn.

The 25-year-old certainly had other career options. An MIT computer science graduate, he could be writing software for the next tech giant. Or he might have gone into academia in computing or applied math or even biology. He could literally be working to cure cancer.

Instead, he goes to work each morning for a high-frequency trading firm. It’s a hedge fund on steroids. He writes software that turns a lot of money into even more money. For his labors, he reaps an uptown salary — and over time his earning potential is unbounded. It’s all part of the plan.

Why this compulsion? It’s not for fast cars or fancy houses. Trigg makes money just to give it away. His logic is simple: The more he makes, the more good he can do.

He’s figured out just how to take measure of his contribution. His outlet of choice is the Against Malaria Foundation, considered one of the world’s most effective charities. It estimates that a $2,500 donation can save one life. A quantitative analyst at Trigg’s hedge fund can earn well more than $100,000 a year. By giving away half of a high finance salary, Trigg says, he can save many more lives than he could on an academic’s salary.

…In many ways, his life still resembles that of a graduate student. He lives with three roommates. He walks to work. And he doesn’t feel in any way deprived. “I wouldn’t know how to spend a large amount of money,” he says.

The full story is here. Here is commentary from Salam and Sanchez. And I have just received the new book by Michael M. Weinstein and Ralph M. Bradburd, The Robin Hood Rules for Smart Giving, an analytical treatment written by two economists.

Why is there no Milton Friedman today?

You will find this question discussed in a symposium at Econ Journal Watch, co-sponsored by the Mercatus Center. Contributors include Richard Epstein, David R. Henderson, Richard Posner, Daniel Houser, James K. Galbraith, Sam Peltzman, and Robert Solow, among other notables. My own contribution you will find here, I start with these points:

If I approach this question from a more general angle of cultural history, I find the diminution of superstars in particular areas not very surprising. As early as the 18th century, David Hume (1742, 135-137) and other writers in the Scottish tradition suggested that, in a given field, the presence of superstars eventually would diminish (Cowen 1998, 75-76). New creators would do tweaks at the margin, but once the fundamental contributions have been made superstars decline in their relative luster.

In the world of popular music I find that no creators in the last twenty-five years have attained the iconic status of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, or Michael Jackson. At the same time, it is quite plausible to believe there are as many or more good songs on the radio today as back then. American artists seem to have peaked in enduring iconic value with Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein, mostly dating from the 1960s. In technical economics, I see a peak with Paul Samuelson and Kenneth Arrow and some of the core developments in game theory. Since then there are fewer iconic figures being generated in this area of research, even though there are plenty of accomplished papers being published.

The claim is not that progress stops, but rather its most visible and most iconic manifestations in particular individuals seem to have peak periods followed by declines in any such manifestation.

A short history of economics at U. Mass Amherst

From Dylan Matthews. Here is an excerpt:

The tipping point, Wolff says, was the denial of tenure for Michael Best, a popular, left-leaning junior professor. “He had a lot of student support, and because it was the 1960s students were given to protest,” Wolff recalls. That, and unrelated personality tensions with the administration, inspired the mainstreamers to start leaving.

That created openings, which, in 1973, the administration started to fill in an extremely unorthodox way. They decided to hire a “radical package” of five professors: Wolff (then at the City College of New York), his frequent co-author and City College colleague Stephen Resnick, Harvard professor Samuel Bowles (who’d just been denied tenure at Harvard), Bowles’s Harvard colleague and frequent co-author Herbert Gintis, and Richard Edwards, a collaborator of Bowles and Gintis’s at Harvard and a newly minted PhD. All but Edwards got tenure on the spot.

…Under those five’s guidance, the department came to specialize in both Marxist economics and post-Keynesian economics, the latter of which presents itself as a truer successor to Keynes’s actual writings than mainstream Keynesians like Paul Samuelson. “When I got there, the department basically had three poles,” said Gerald Epstein, who arrived as a professor in 1987. “There was the postmodern Marxian group, which was Steve Resnick and Richard Wolff, and then there was a general radical economics group of Sam Bowles and Herb Gintis, and then a Keynesian/Marxian group. Jim Crotty was the leader of that group.” Suffice it to say, most mainstream departments have zero Marxists, period, let alone Keynesian/Marxist hybrids or postmodern Marxists.

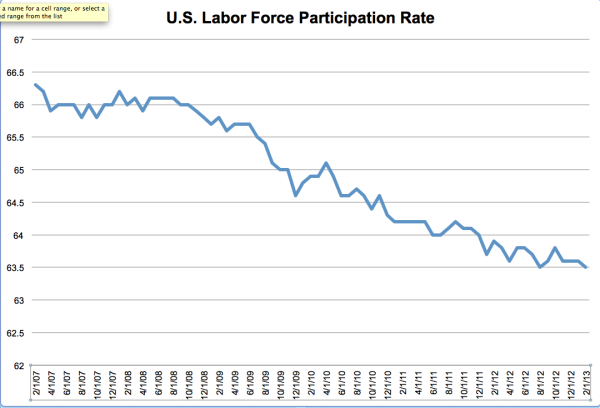

And yet the labor force participation rate is still falling

From Peter Coy, source here. (And broken down by age here, I never find that disaggregation reassuring however, since the elderly are working more and the young less.) Here are related comments and charts from Dylan Matthews. Yet perhaps Felix Salmon has the clincher:

The number of multiple jobholders rose by 340,000 this month, to 7.26 million — a rise larger than the headline rise in payrolls. Which means that one way of looking at this report is to say that all of the new jobs created were second or third jobs, going to people who were already employed elsewhere. Meanwhile, the number of people unemployed for six months or longer went up by 89,000 people this month, to 4.8 million, and the average duration of unemployment also rose, to 36.9 weeks from 35.3 weeks.

Catherine Rampell discusses the rise of part-time work, very important stuff. Here are relevant remarks by Pethoukis. Here is more on the long-term unemployed.

By the way, my point is not to deny the “good news” aspects of the report, as summarized by Matthews and discussed elsewhere. I would instead put it this way: we are recovering OK from the AD crisis, but the structural problems in the labor market are getting worse. It’s becoming increasingly clear those structural problems were there all along and also that they are a big part of the real story. On the AD side, mean-reversion really is taking hold, as it should and as is predicted by most of the best neo-Keynesian models.

The 20 Greatest Songs About Work?

The list is here. Number one is Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Sixteen Tons,” followed by Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm.” “Atlantic City” would not have been my Springsteen pick but overall the list is better than expected. There is, however, an odd under-representation of folk music, see for instance this list.

Why are the service sectors underrepresented on such lists? There is “Dr. Robert,” “Lawyers, Guns, and Money,” “Police and Thieves,” and many others from the more stagnant sectors of the economy, although arguably police productivity has risen quite a bit.

For the pointer I thank the estimable Chug.