Results for “unemployment” 675 found

The labor market mismatch model

This paper studies the cyclical dynamics of skill mismatch and quantifies its impact on labor productivity. We build a tractable directed search model, in which workers differ in skills along multiple dimensions and sort into jobs with heterogeneous skill requirements. Skill mismatch arises because of information frictions and is prolonged by search frictions. Estimated to the United States, the model replicates salient business cycle properties of mismatch. Job transitions in and out of bottom job rungs, combined with career mobility, are key to account for the empirical fit. The model provides a novel narrative for the scarring effect of unemployment.

That is from the new JPE, by Isaac Baley, Ana Figueiredo, and Robert Ulbricht. Follow the science! Don’t let only the Keynesians tell you what is and is not an accepted macroeconomic theory.

A college degree ain’t what it used to be

Labor market outcomes for young college graduates have deteriorated substantially in the last twenty five years, and more of them are residing with their parents. The unemployment rate at 23-27 year old for the 1996 college graduation cohort was 9%, whereas it rose to 12% for the 2013 graduation cohort. While only 25% of the 1996 cohort lived with their parents, 31% for the 2013 cohort chose this option. Our hypothesis is that the declining availability of ‘matched jobs’ that require a college degree is a key factor behind these developments. Using a structurally estimated model of child-parent decisions, in which coresidence improves college graduates’ quality of job matches, we find that lower matched job arrival rates explain two thirds of the rise in unemployment and coresidence between the 2013 and 1996 graduation cohorts. Rising wage dispersion is also important for the increase in unemployment, while declining parental income, rising student loan balances and higher rental costs only play a marginal role.

That is from a new NBER paper by Stefania Albanesi, Rania Gihleb, and Ning Zhang.

A better way to think about wage pressures than the Phillips curve

Most economists maintain that the labor market in the United States is ‘tight’ because unemployment rates are low. They infer from this that there is potential for wage-push inflation. However, real wages are falling rapidly at present and, prior to that, real wages had been stagnant for some time. We show that unemployment is not key to understanding wage formation in the USA and hasn’t been since the Great Recession. Instead, we show rates of under-employment (the percentage of workers with part-time hours who would prefer more hours) and the rate of non-employment which includes both the unemployed and those out of the labor force who are not working significantly reduce wage pressures in the United States. This finding holds in panel data with state and year fixed effects and is supportive of a wage curve which fits the data much better than a Phillips Curve. We find no role for vacancies; the V:U ratio is negatively not positively associated with wage growth since 2020. The implication is that the reserve army of labor which acts as a brake on wage growth extends beyond the unemployed and operates from within and outside the firm.

We are the reserve army of the unemployed! Here is the full paper from David G. Blanchflower, Alex Bryson, and Jackson Spurling. The results also suggest that getting inflation under control will be easy than some alternative accounts might indicate, and in that sense this is mild cause for macroeconomic optimism, relatively speaking that is.

These ten veteran ex-Lakers from the 2021-2022 season, however, are still unemployed (ESPN).

Job security is not getting worse

There is a widespread belief that work is less secure than in the past, that an increasing share of workers are part of the “pprecariat”. It is hard to find much evidence for this in objective measures of job security, but perhaps subjective measures show different trends. This paper shows that in the US, UK, and Germany workers feel as secure as they ever have in the last thirty years. This is partly because job insecurity is very cyclical and (pre-COVID) unemployment rates very low, but there is also no clear underlying trend towards increased subjective measures of job insecurity. This conclusion seems robust to controlling for the changing mix of the labor force, and is true for specific sub-sets of workers.

That is from Alan Manning and Graham Mazeine, forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Is Germany really with the program? (NYT) I liked this sentence: ““The government has made some courageous decisions, but it can seem afraid of its own courage.”

2. New Yorker profile of Nakamura.

3. Did Yves Klein sell the very first NFT?

4. Jason Furman on “running labor markets hot” — don’t expect higher real wages! (WSJ), #Thegreatforgetting

5. Complete works of Voltaire now available in 205 volumes.

6. The neurodiverse, work from home, and cybersecurity (WSJ).

Robot Rentals

Economists have long said that r, the interest rate, is the rental rate for capital in the same way that w is the rental rate (wage rate) for labor. Now it’s becoming literally true:

Bloomberg: The robots are coming—and not just to big outfits like automotive or aerospace plants. They’re increasingly popping up in smaller U.S. factories, warehouses, retail stores, farms, and even construction sites.

…a nascent trend of offering robots as a service—similar to the subscription models offered by software makers, wherein customers pay monthly or annual use fees rather than purchasing the products—is opening opportunities to even small companies. That financial model is what led Thomson to embrace automation. The company has robots on 27 of its 89 molding machines and plans to add more. It can’t afford to purchase the robots, which can cost $125,000 each, says Chief Executive Officer Steve Dyer. Instead, Thomson pays for the installed machines by the hour, at a cost that’s less than hiring a human employee—if one could be found, he says. “We just don’t have the margins to generate the kind of capital necessary to go out and make these broad, sweeping investments,” he says. “I’m paying $10 to $12 an hour for a robot that is replacing a position that I was paying $15 to $18 plus fringe benefits.”

…Formic is offering to set up robots and charge as little as $8 an hour, aiming first at the most tedious tasks, such as packing and unpacking products and feeding materials into existing machines. The potential market is huge, and it will only grow as the robots become more sophisticated, Farid says.

Robots will bring manufacturing back to America. A robot workforce should also make human unemployment less volatile because a robot workforce can be increased or shrunk quickly and isn’t worried about nominal wage stickiness. Also, as of yet robots don’t unionize. Robot wages will make the minimum wage more salient. Working out the interactions between a monopsony buyer of labor facing a perfectly elastic supply of robots will be interesting.

Labor supply still really matters

We also document a sharp decline in desired work hours during the pandemic that persists through the end of 2021 and is roughly double the drop in the labor force participation rate. Ignoring the decline in desired hours overstates the degree of underutilization by 2.5 percentage points (12.5%). Our findings suggest that, as of 2021Q4, the labor market is tighter than suggested by the unemployment rate and the adverse labor supply effect of the pandemic is more pronounced than implied by the labor force participation rate.

That is from a new NBER working paper by R. Jason Faberman, Andreas I. Mueller, and Ayşegül Şahin.

*Labor Econ Versus the World*

The author is Bryan Caplan and the subtitle is Essays on the World’s Greatest Market. It is a collection of his best blog posts on labor markets over the last fifteen years or so. A Bryan blog post from 2015 gives a good overview of much of the book, which you can read as pushback against a lot of doctrines held by other people, including the mainstream:

What are these “central tenets of our secular religion” and what’s wrong with them?

Tenet #1: The main reason today’s workers have a decent standard of living is that government passed a bunch of laws protecting them.

Critique: High worker productivity plus competition between employers is the real reason today’s workers have a decent standard of living. In fact, “pro-worker” laws have dire negative side effects for workers, especially unemployment.

Tenet #2: Strict regulation of immigration, especially low-skilled immigration, prevents poverty and inequality.

Critique: Immigration restrictions massively increase the poverty and inequality of the world – and make the average American poorer in the process. Specialization and trade are fountains of wealth, and immigration is just specialization and trade in labor.

Tenet #3: In the modern economy, nothing is more important than education.

Critique: After making obvious corrections for pre-existing ability, completion probability, and such, the return to education is pretty good for strong students, but mediocre or worse for weak students.

Tenet #4: The modern welfare state strikes a wise balance between compassion and efficiency.

Critique: The welfare state primarily helps the old, not the poor – and 19th-century open immigration did far more for the absolutely poor than the welfare state ever has.

Tenet #5: Increasing education levels is good for society.

Critique: Education is mostly signaling; increasing education is a recipe for credential inflation, not prosperity.

Tenet #6: Racial and gender discrimination remains a serious problem, and without government regulation, would still be rampant.

Critique: Unless government requires discrimination, market forces make it a marginal issue at most. Large group differences persist because groups differ largely in productivity.

Tenet #7: Men have treated women poorly throughout history, and it’s only thanks to feminism that anything’s improved.

Critique: While women in the pre-modern era lived hard lives, so did men. The mating market led to poor outcomes for women because men had very little to offer. Economic growth plus competition in labor and mating markets, not feminism, is the main reason women’s lives improved.

Tenet #8: Overpopulation is a terrible social problem.

Critique: The positive externalities of population – especially idea externalities – far outweigh the negative. Reducing population to help the environment is using a sword to kill a mosquito.

Yes, I’m well-aware that most labor economics classes either neglect these points, or strive for “balance.” But as far as I’m concerned, most labor economists just aren’t doing their job. Their lingering faith in our society’s secular religion clouds their judgment – and prevents them from enlightening their students and laying the groundwork for a better future.

I will say this: Labor Econ Versus the World, while not written as a book per se, still is the best free market book on labor economics I know of. And it is very reasonably priced. I agree with much of what is in this book, but by no means all of it. I’ll consider my differences with it in a separate blog post, to come tomorrow.

Where are the Variant Specific Boosters?

I wasn’t shocked at the failures of the CDC and the FDA. I am shocked that our government still can’t get its act together in the third year of the pandemic. Consider how lucky, yes lucky, we have been. Here’s Eric Topol:

…the original vaccines were targeted to the Wuhan ancestral strain’s spike protein from 2019. The spike protein, no less the rest of the original SARS-CoV-2 structure, is almost unrecognizable now in the form of the Omicron strain (see antigenic drift from prior post). While there’s naturally been much focus on the extraordinary number of mutations in the receptor binding domain and the rest of the spike protein, over 50 mutations are spread out throughout Omicron, making the prior major variants of concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta) lightweights with respect to changes in structure that are not just linear or uni-dimensional. Each mutation can interact with others (epistasis); any mutation or combination of mutations has the potential to change the 3D structure of the virus. In this sense, Omicron is an overwhelming reboot of the ancestral strain.

Omicron is very different from the Wuhan ancestral strain and it’s only a matter of luck that the vaccines continue to work and that Omicron is likely less severe than Delta. Don’t tell me that viruses evolve to be less severe over time–that isn’t correct in theory or practice. The most one might say is that a very deadly virus may be difficult to transmit but that only closes off a small part of the evolutionary design-space. There is plenty of room for transmission and lethality to both increase. So the vaccines continue to work well. We got lucky. But for how long will our luck last? Do we really have to wait for a more transmissible, more deadly, more vaccine escaping variant before we act?

Where are the variant-specific boosters? The FDA has said they would approve them quickly, without new efficacy trials so I don’t think the problem is primarily regulatory. Why not catch-up to the virus and maybe even get a jump ahead with pan-coronavirus vaccines?

More generally, in our February 2021 paper in Science my co-authors and I argued that we were still leaving trillion dollar bills on the sidewalk by not investing in more vaccine capacity. I am sorry to say that we were right. Why the failure to invest more broadly?

Mostly I blame American lethargy. After 9/11 the country was angry and united and we had troops in Afghanistan within a matter of weeks and we had taken over the country in a matter of months. For better or worse, we acted quickly and with resolve. Yet, when the virus was killing at 9/11 levels every day the public never reached the same level of anger or resolve. Even now Congress has spent trillions on unemployment insurance, business protection, money for schools and stimulus but has not passed the American Pandemic Preparedness Plan, a pretty decent, mostly science-based investment plan.

80,000 hours ranks research and investment against Global Catastrophic Biologic Risk (GCBR) as among the most pressing and yet tractable problems to work on and yet they estimate that quality-adjusted only about a billion dollars is being spent on these risks. Moreover, COVID doesn’t even count as a GCBR, i.e. 80000 hours at least recognizes that things could be much worse.

I understand that future people don’t vote but even so I expected a little bit more foresight.

Today’s labor market report

Unemployment is at 3.9%, and can’t get much better. In the new report just 199,000 jobs were added. Job growth is slowing and that is a pre-omicron phenomenon. Labor force participation has not been so low since 1977. The great economic myth of the last thirteen or so years is that you can get the labor market to pre-Covid Trump administration levels and keep it there just by having enough “aggregate demand.” I am all for sufficient aggregate demand, to be clear, but I don’t overrate it either.

People are starting to rethink what is going on. All coherent stories have to involve…the supply side of the labor market. Which is precisely what the orthodoxy had been telling you to ignore. Average is Over.

Labor supply is behaving strangely

In an unusual job posting on Facebook, a pizzeria in Alabama has offered to “literally hire anyone,” a sign of how restaurants are still struggling to attract workers.

“We will literally hire anyone,” Dave’s Pizza, in the Birmingham suburb of Homewood, said in a Facebook post Wednesday. “If you’re on unemployment and can’t find a job, call us; we’ll hire you.”

What if they gave a job and nobody came? Here is the story, via the excellent Samir Varma. And elsewhere, via Heather Long:

Face masks are required again in major US auto factories and, according to Ford CEO Jim Farley, that has some workers deciding not to show up for work. In some factories, absentee rates can exceed 20%, he said in an interview with CNN Business.

“When a fifth of your workforce isn’t coming in, in a manufacturing operation where everyone has their job and you don’t know who’s going to be missing every day, man, it’s really challenging,” Farley said.

Labor supply is…behaving strangely. And here is a very good Scott Sumner post on unemployment insurance. Might one of the simpler lessons here be that when job circumstances and working conditions remain uncertain, it is much harder for markets to make good job matches?

How good was Paul Samuelson’s macroeconomics?

Reading the new Nicholas Wapshott book and also Krugman’s review (NYT) of it, it all seemed a little too rosy to me. So I went back and took a look at Paul Samuelson the macroeconomist. I regret that I cannot report any good news, in fact Samuelson was downright poor — you might say awful — as a macroeconomist.

For instance, during the early 1970s there was a debate about President Nixon’s 1971 wage and price controls. There is some disagreement about the actual stance of Samuelson, as Wapshott (p.152) claims Samuelson opposed Nixon’s wage and price controls, but that doesn’t seem to be true. The Los Angeles Times for instance reported Samuelson opining as follows: “With the wage and price controls, he [Nixon] assured a more rapid short-term economic recovery, and made it absolutely certain he would be the overwhelming victor in the 1972 election.” Maybe that is not quite a full endorsement, but consider Samuelson’s remarks on the August 17, 1971 ABC Evening News: “I don’t think that a ninety-day freeze is going to solve the problem of inflation. But it’s a first move toward some kind of an incomes policy. Benign neglect did not work. It’s time the president used his leadership…We’re better off this Monday morning than we were last Friday. Friday was an untenable situation.”[1]

Really?

For Samuelson and many other Keynesians of his era, it was mostly about wage-push inflation. Do you know what my take would have been?: “The wage and price controls are neither good microeconomic nor good macroeconomic policy.” Samuelson did not come anywhere near to uttering such words. In October 1971, Samuelson argued that Nixon’s NEP [New Economic Policy], which included both severing the tie of the dollar to gold and wage and price controls, was “necessary,” and that the wage and price controls were working better than might have been expected.[2]

In October 1971, Samuelson also argued that the Fed should continue to let the money supply grow, to stave off the risk of a liquidity crisis occasioned by America’s lingering involvement in the Vietnam War (what??…if this is fear of a Bretton Woods collapse, print fewer dollars, besides Samuelson wanted to end Bretton Woods). He said he favored presidential “guideposts” to lower the rate of price inflation from four to three percent, but didn’t favor explicit wage and price controls because it wasn’t enough of an “emergency” situation. That is the extent of his opposition to wage and price controls – lukewarm at best, not objecting in principle, contradicting his earlier stances, and showing a poor understanding of monetary economics more broadly. You don’t have to be a hardcore monetarist to realize that continued money supply growth, in an expansionary period, combined with presidential “guideposts” to lower rates of price inflation, was simply an incorrect view.

In a 1974 piece, Samuelson continued to insist, as he had argued in the past, that the inflation of that era was cost-push inflation, and not driven by the money supply. He also asserted (without evidence) that full employment and price stability were incompatible. In one 1971 piece he made the remarkable and totally false assertion that: “…with our population and productivity growing, it takes more than a 4 per cent rate of real growth just to hold unemployment constant at a high level.”[3]

Really?

In other words, his basic model was just flat out wrong. More generally, the Samuelson Newsweek columns of that era make repeated, dogmatic, and arbitrary stabs at forecasting macroeconomic variables without much humility or soundness in the underlying model.

Milton Friedman did have an overly simplified view of the money supply, as many of his critics have alleged and as Scott Sumner would confirm. But as a macroeconomist he was far, far ahead of Paul Samuelson.

Don’t forget how bad macro was before Friedman came along.

[1] For The Los Angeles Times, see Hiltzi (1994), and also see “Questions and Answers: Paul A. Samuelson,” Newsweek, October 4, 1971. For the ABC News remarks, see Nelson (2020, volume 2, p.267).

[2] See “Questions and Answers: Paul A. Samuelson,” Newsweek, October 4, 1971.

[3] See Paul Samuelson, “Coping with Stagflation” Newsweek, August 19, 1974, and for the 1971 remarks see “How the Slump Looks to Three Experts” Newsweek, Oct.18, 1971. On the four percent claim, see Paul A. Samuelson, “Nixon Economics,” Newsweek, August 2, 1971.

Ray C. Fair on price inflation

This paper uses an econometric approach to examine the inflation consequences of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Price equations are estimated and used to forecast future inflation. The main results are: (1) The data suggest that price equations should be specified in level form rather than in first or second difference form. (2) There is some slight evidence of nonlinear demand effects on prices. (3) There is no evidence that demand effects have gotten smaller over time. 4) The stimulus from the act combined with large wealth effects from past household saving, rising stock prices, and rising housing prices is large and is forecast to drive the unemployment rate down to below 3.5 percent by the middle of 2022. 5) Given this stimulus, the inflation rate is forecast to rise to slightly under 5 percent by the middle of 2022 and then comes down slowly. 6) There is considerable uncertainty in the point forecasts, especially two years out. The probability that inflation will be larger than 6 percent next year is estimated to be 31.6 percent. 7) If the Fed were behaving as historically estimated, it would raise the interest rate to about 3 percent by the end of 2021 and 3.5 percent by the end of 2022 according to the forecast. This would lower inflation, although slowly. By the middle of 2022 inflation would be about 1 percentage point lower. The unemployment rate would be 0.5 percentage points higher.

As I do not think the correct answers here are close to certain, I am happy to continue to survey a broad range of opinion. Stay tuned…

Here is the link, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. As for the markets, here is yesterday’s report from Neil Irwin:

“So we’re at 1.2% 10-year Treasury yields with 5.4% year-over-year inflation. Very normal very cool.”

As I interpret those numbers, the market expects inflationary pressures, the Fed to respond, but that response will induce a recession. Stay tuned…

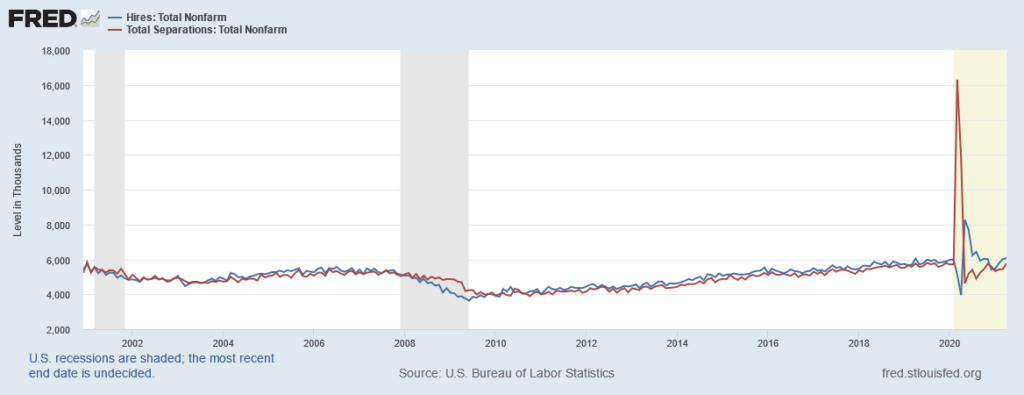

The Pandemic JOLTS

The 2009 recession was big but it followed a very familiar pattern–job separations were a little bit larger than job hires and this lasted for a little less than year which drove up unemployment rates. Unemployment rates then declined slowly as hires became a little bit larger than separations. Now look at the pandemic recession! Separations triple from normal–absolutely unprecedented. Hires then rebound at a slower rate than separations but at a much faster rate than in any previous recession (I haven’t bothered correcting for population since the differences are so large.)

I don’t know entirely what to make of this but we are still debating the Great Depression and the Great Recession so the Pandemic Recession will provide data and questions for a generation of economists. Why, for example, are supply shocks seemingly so much easier for an economy to handle than demand shocks? And why are some demand shocks worse than others? The dot com bust was at least as big a decline in wealth than the housing bust in 2009 but the latter resulted in a much bigger recession. How much was due to policy? How much was due to the fact that the financial system wasn’t so involved in the dot com bust or the pandemic recession? Finance often seems like it doesn’t do so much but why then do things go so badly when the financial system is impeded?

Thursday assorted links

1. Is this possible?: “Criminals may have stolen as much as half of the unemployment benefits the U.S. has been pumping out over the past year, some experts say.”

2. When should ngdp be unstable?

3. Is Nero underrated? (New Yorker)

4. Sixty times the speed of sound? (USS Princeton radar team and pilot source, also a good presentation of the multiple data sources which are neglected by West and PewdiePie.) And here is the common briefing message given to the ex-presidents.

5. Where are the Chinese elephants going and why?

6. Darrell Duffie argues for CBDC.

7. Kristof on the new Claudia Goldin book (NYT).