Results for “coup” 640 found

How Rapidly ‘First Doses First’ Came to Britain

Tim Harford writes about the whiplash he experienced from the debate over delaying second doses in Britain.

What a difference a couple of weeks makes. In mid-December, I asked a collection of wise guests on my BBC radio programme How to Vaccinate the World about the importance of second doses. At that stage, Scott Gottlieb, former head of the US Food and Drug Administration, had warned against stockpiling doses just to be sure that second doses were certain to be available, Economists such as Alex Tabarrok of George Mason University had gone further: what if we gave people single doses of a vaccine instead of the recommended pair of doses, and thus reached twice as many people in the short term? This radical concept was roundly rejected by my panel

…. “This is an easy one, Tim, because we’ve got to go with the scientific evidence,” said Nick Jackson of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. “And the scientific evidence is that two doses is going to provide the best protection.”

My other guests agreed, and no wonder: Jackson’s view was firmly in the scientific mainstream three weeks ago. But in the face of a shortage of doses and a rapidly spreading strain of “Super-Covid”, the scientific mainstream appears to have drifted. The UK’s new policy is to prioritise the first dose and to deliver the second one within three months rather than three weeks…..the recommendation comes not from ministers but from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

Strikingly, many scientists have given the move their approval.

See also Tyler’s previous post on this theme.

By the way, if the J&J single-dose vaccine comes in at say 80% effective it is going to be interesting to see how people go from ‘a single-dose at 80% effective is too dangerous to allow for 8-12 weeks’ to ‘isn’t it great we have a single-dose 80% effective vaccine!’.

My Conversation with the excellent Noubar Afeyan

Among his other achievements, he is the Chairman and co-founder of Moderna. Here is the audio and video and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

He joined Tyler to discuss which aspect of entrepreneurship is hardest to teach, his predictions on the future of gene editing and CRISPR technology, why the pharmaceutical field can’t be winner takes all, why “basic research” is a poor term, the secret to Boston’s culture of innovation, the potential of plant biotech, why Montreal is (still) a special place to him, how his classical pianist mother influenced his musical tastes, his discussion-based approach to ethical dilemmas, how thinking future-backward shapes his approach to business and philanthropy, the blessing and curse of Lebanese optimism, the importance of creating a culture where people can say things that are wrong, what we can all learn by being an American by choice, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

AFEYAN:

I should point out, Tyler, what these people don’t yet realize is that mRNA, in addition to being unique in that it’s really the first broadly applied code molecule, information molecule that is used as a medicine and with all the advantages that come with information — digital versus analog — or where you actually have to do everything bespoke, the way drugs usually work.

The other major advantage that it has is that it is something that is actually taking advantage of nature. There was a lot of know-how we had going into this around how the process could be done. In fact, let me tell you the parallel that we used.

We have a program in cancer vaccines. You might say, “What does a cancer vaccine have to do with coronavirus?” The answer is the way we work with cancer vaccines is that we take a patient’s tumor, sequence it, obtain the information around all the different mutations in that tumor, then design de novo — completely nonexistent before — a set of peptides that contain those mutations, make the mRNA for them, and stick them into a lipid nanoparticle, and give it back to that patient in a matter of weeks.

That has been an ongoing — for a couple of years — clinical trial that we’re doing. Well, guess what? For every one of those patients, we’re doing what we did for the virus, over and over and over again. We get DNA sequence. We convert it into the antigenic part. We make it into an RNA. We put it in a particle. In an interesting way, we had interesting precedents that allowed us to move pretty quickly.

And at the close:

Imagine if all of us were also born imagining a better future for ourselves. Well, we should be, but we’ve got to work to get that. An immigrant who comes here understands that they’ve got to work to get that. They have to adapt. The problem is, if you’re born here, you may not actually think that you’ve got to work to get that. You might think you’re born into it.

This will be a funny thing to say, and I apologize to anybody that I offend. If we were all Americans by choice, we’d have a better America because Americans by choice, of which I’m one, actually have a stronger commitment to whatever it takes to make America be the place I chose to be, versus not thinking about that as a core responsibility.

Definitely recommended, he is working to save many many lives, and with great success.

Daughter-driven divorce?

Are couples with daughters more likely to divorce than couples with sons? Using Dutch registry and U.S. survey data, we show that couples with daughters face higher risks of divorce, but only when daughters are 13 to 18 years old. These age-specific results run counter to explanations involving overarching, time-invariant preferences for sons and sex-selection into live birth. We propose another explanation that involves relationship strains in families with teenage daughters. In subsample analyses, we find larger child-gender differences in divorce risks for parents whose attitudes towards gender-roles are likely to differ from those of their daughters and partners. We also find survey evidence of relationship strains in families with teenage daughters.

That is from a new paper by Jan Kabátek and David C Ribar. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

From the comments, on Congressional cybersecurity, from Gomer

One or two simple points

Fabio Rojas says not a coup. Naunihal Singh agrees, and he is the expert in this area. I agree as well. But still it matters a lot that to many people, including foreigners, it looks like one. Is it crazy to think that a police force protecting Congress should stand its ground no matter what, even if that means escalating the level of force? I don’t understand why that view isn’t being discussed more. What is al Qaeda thinking now?

My main model revision was that the police have been more radicalized than I had thought, and some of them seemed to welcome the intruders, let them in, took selfies with them, etc. Why didn’t they arrest more of the felons? Why were the riot police of D.C. so very slow to respond? This problem of die Polizeiweltanschauung remains underdiscussed.

How many women in this group? A few, but here is a redux of my May 2016 post “What the Hell is Going On?”.

For the day, stocks were up and gold was down. But still it is justified to be worried about the next two weeks. In the meantime, Mormons should rise in status yet again.

From David Splinter, from my email

This is all David:

A related paper by BEA came out today with their updated distributional estimates of personal income. Marina Gindelsky has done a lot of work to produce these estimates.

I have a couple new papers on tax progressivity and redistribution that may be of interest to you. Both used CBO data to avoid the PSZ-AS differences. Abstracts below.

The first paper is about the ends of the distribution: tax progressivity has increased significantly since 1979 (and steadily since 1986) due to more generous tax credits for the bottom, while average tax burdens of the top have been relatively unchanged because lower marginal rates were offset by decreased use of tax shelters. The online appendix shows why the CBO estimates differ from those of Saez and Zucman (see Fig. B7 at the end; it’s mostly due to refundable credits at the bottom and imputed income at the top) and the Heathcote et al. paper you blogged about a couple months ago (it’s technical differences and their inclusion of some transfers, but their most similar measure of tax progressivity was not flat—it increased 21 percent since 1979).

The second paper, with Adam Looney and Jeff Larrimore, is about the middle of the distribution. Since 1979, we found that non-elderly middle-class market income increased 39 percent in real per person terms. The increase was 57 percent when accounting for taxes and transfers. This seems to fit with the “updated” view of stagnation—expanding male wages to also look at untaxed compensation and including female compensation and taxes/transfers shows larger median growth. But there was a structural break in 2000. Before then, middle-class incomes grew at the same rate before and after taxes and transfers, and since then income after taxes and transfers grew three times faster (Fig. 6 on page 19). We don’t discuss the recent market income slowdown (maybe related to the debated labor share break around 2000), but we show that the additional fiscal support that filled the gap looks like an unsustainable way to boost middle-class disposable incomes going forward.”

Inelastic demand

Last Thursday, Dale Mclaughlan bought a Jet Ski.

On Monday, the 28-year-old Scotsman was sentenced to four weeks in jail.

What happened on the three days in between, according to court documents, may be one of the more unusual instances of rule-flouting during the coronavirus pandemic.

The day after purchasing the watercraft, Mr. Mclaughlan set off at 8 a.m. for what he thought would be a 40-minute trip from the southwestern coast of Scotland to his girlfriend’s home on the Isle of Man, between England and Ireland. He later told the authorities that he had never ridden a Jet Ski before and that bad weather on the Irish Sea caused the trip to stretch to four and a half hours.

Mr. Mclaughlan finally reached his girlfriend on Friday night, after walking 15 miles from the Isle of Man’s coast to her home in its capital, Douglas. The couple spent the weekend enjoying the city’s nightlife, but their reunion was cut short, when he was arrested and later charged with one count of violating the Isle of Man’s coronavirus restrictions.

On Monday, he received a four-week jail sentence.

Here is the full NYT story. The Isle of Man keeps out visitors, and has managed to keep out the coronavirus as well.

My Conversation with Edwidge Danticat

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the CWT summary:

She joined Tyler to discuss the reasons Haitian identity and culture will likely persist in America, the vibrant Haitian art scenes, why Haiti has the best food in the Caribbean, how radio is remaining central to Haitian politics, why teaching in Creole would improve Haitian schools, what’s special about the painted tap-taps, how tourism influenced Haitian art, working with Jonathan Demme, how the CDC destroyed the Haitian tourism industry, her perspective on the Black Lives Matter movement, why she writes better at night, the hard lessons of Haiti’s political history, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Now, in all of these conversations, there’s a segment where I present to the guest my favorite Haitian proverbs, and he or she reacts. Are you ready for a few?

DANTICAT: All right. You’ve been sharing Haitian proverbs with your guests?

COWEN: Here’s one. “After the dance, the drum is heavy.”

DANTICAT: Oh my god.

COWEN: What does that mean to you?

DANTICAT: Aprè dans, tanbou lou. I actually have a book called After the Dance. It’s on Carnival. Yes, for me, it means that there are consequences to everything, even the most joyful thing. You have to be prepared for the consequences of things that you’ve done.

It’s something that my mom used to say quite a bit, too. If you have just had a really big celebration, or if you waited too late to do your homework because you’re having a good time watching a program you like, she was like, “Aprè dans, tanbou lou.” After the dance, the drum is heavy. It’s like the morning-after, hangover situation and the most joyful outcome, but really, that there are consequences to everything.

COWEN: Here’s another one. “It is the owner of the body who looks out for the body.”

DANTICAT: Oh, this one. You will not believe how much we hear that these days. Se mèt kò ki veye kò. It’s something that we say a lot now in the coronavirus era. You hear it on the radio. You hear people say it when they talk to their neighbors. Se mèt kò ki veye kò. That means that, really, you are the best person to take care of yourself.

If you’re saying, “Wear your mask when you go out during the coronavirus era.” “Wash your hands.” It’s like the best, the most qualified person to take care of you is you. It’s not the doctor. It’s not your loved one. Se mèt kò ki veye kò. It’s the owner of the body who takes care of the body. It’s like, “Watch out for yourself.” It’s very good advice these days.

COWEN: “When they want to kill a dog, they say it’s crazy.”

DANTICAT: Yes, that’s the dehumanization. I guess that’s fake news. [laughs] It’s connected to the fake news. If you want to diminish or slight someone, you call them names. So that’s also a timely one, I think.

COWEN: How about this one? “The constitution is paper; the bayonet is steel.”

DANTICAT: Yes. Again, back to our conversation about dictatorship, in a way. I believe that one was often cited by one of the generals, actually, during the ’90s, during the coup d’état, or it might have been even before. I think it speaks to the fragility of documents like the constitution. Yesterday was Constitution Day in the US, so that might also apply here.

It’s that whole thing with freedom. Freedom is something that we have to always keep watching out it doesn’t slip away because, sometimes, we think these documents or these rules are set in stone. I think this general who kept saying this was saying, “Well, I have the weapons.” It’s kind of paper, rock scissors. Which is stronger?

COWEN: “When the mapou tree dies, goats would eat its leaves.”

DANTICAT: Yes. This one, I think, is about humility because we have this expression that we say when someone has died who has contributed a great deal to our culture: we say that a mapou has fallen. A mapou is a soft cotton tree, it’s a kind of sacred tree, and it’s also a big tree that lasts forever. It’s a regal institution, a mapou.

What this one is saying, actually, the goat is a meager creature compared to a mapou, and there’s no way a goat would actually be able to access the leaves of a mapou, but when it dies, it falls. I’ve always heard that proverb as a way of encouraging humility, that all our leaves are vulnerable to the goat, if you will. [laughs]

COWEN: One more proverb, “Beyond the mountain is another mountain.”

DANTICAT: Yes. Dèyè mòn gen mòn.

COWEN: That’s a very famous one.

DANTICAT: Yes. I actually use that a lot myself. One of my neighbors just passed away, and she used to use that proverb a lot. I think it means that no matter what, we can see there is more. I think it’s about there’s more to everything than what we see.

It also speaks to the physical layout of Haiti because it’s a very mountainous place. Ayiti. The Arawak called it Ayiti. It actually means land of the mountains, and it’s physically true. If you’re traveling across Haiti, literally, there’s always a mountain physically behind a mountain, but in a spiritual sense, it also means that there’s always more.

Recommended. And I thank Carl-Henri Prophète for assistance with the transcription.

Rational Criminals, Irrational Lawmakers

Columnist Phil Matier writes in the SFChroncile about rampant, brazen shoplifting in San Francisco.

After months of seeing its shelves repeatedly cleaned out by brazen shoplifters, the Walgreens at Van Ness and Eddy in San Francisco is getting ready to close.

…“All of us knew it was coming. Whenever we go in there, they always have problems with shoplifters, ” said longtime customer Sebastian Luke, who lives a block away and is a frequent customer who has been posting photos of the thefts for months. The other day, Luke photographed a man casually clearing a couple of shelves and placing the goods into a backpack.

Most of the remaining products were locked behind plastic theft guards, which have become increasingly common at drugstores in recent years.

But at Van Ness Avenue and Eddy Street, even the jugs of clothing detergent on display were looped with locked anti-theft cables.

When a clerk was asked where all the goods had gone, he said, “Go ask the people in the alleys, they have it all.”

No sooner had the clerk spoken than a man wearing a virus mask walked in, emptied two shelves of snacks into a bag, then headed back for the door. As he walked past the checkout line, a customer called out, “Sure you don’t want a drink with that?”

…Under California law, theft of less than $950 in goods is treated as a nonviolent misdemeanor. The maximum sentence for petty theft is six months in county jail. But most of the time the suspect is released with conditions attached.

Some stores have hired private security firms or off-duty police officers to deter would-be thieves. But security is expensive and can cost upward of $1,000 a day. Add in the losses from theft, and the cost of doing business can become too high for a store to stay open.

Perhaps San Francisco helps us with Tyler’s “solve for the Seattle Equilibrium” challenge.

Bringing religion back into business

Evan Sharp, the co-founder of Pinterest, hired Sacred Design Lab to categorize all major religious practices and think of ways to apply them to the office. They made him a spreadsheet.

“We pulled together hundreds of practices from all these different religions and cultural practices and put them in a spreadsheet and just tried to categorize them by emotional state: which ones are relevant when you’re happy, which are relevant when you’re angry, and a couple other pieces of metadata,” Mr. Sharp said.

When he had the data, he said, he took a few days and read it all. “This sounds embarrassingly basic,” he said, “but it really reframed parts of religion for me.”

It made him realize how many useful tools existed inside something as old-fashioned as his childhood church. “Some of the rituals I grew up with in Protestantism really have emotional utility,” he said. And Mr. Sharp saw that it was good.

And:

Rev. Phillips, the minister, had a few other ideas. She suggested using a repetitive meeting structure, which can be calming for participants. This might take the form of starting each team meeting with the same words, a sort of corporate incantation.

Others suggested workers each light a candle at the start of a meeting, or pick up a common object that everyone is likely to have in their homes.

“How about trying actual religion?” I hear Ross Douthat saying… Here is the full Nellie Bowles NYT article, after a slow start interesting throughout, though no real discussion of Wokeness, which of course is what the tech companies actually are doing.

Friday assorted links

1. Bettye LaVette reminiscences, racy.

2. GMU enrollment this year is up two percent.

3. Some Doing Business ratings may have been manipulated (WSJ).

4. Chinese calculations in the Himalayan clashes with India.

5. “…she forced her husband to cancel his planned death…”

6. NASA has patented a new route to the moon.

7. Pandit Jasraj, RIP (NYT).

The new quicker, cheaper, supply chain robust saliva test

The FDA has just approved a new and important Covid-19 test:

“Wide-spread testing is critical for our control efforts. We simplified the test so that it only costs a couple of dollars for reagents, and we expect that labs will only charge about $10 per sample. If cheap alternatives like SalivaDirect can be implemented across the country, we may finally get a handle on this pandemic, even before a vaccine,” said Grubaugh.

One of the team’s goals was to eliminate the expensive saliva collection tubes that other companies use to preserve the virus for detection. In a separate study led by Wyllie and the team at the Yale School of Public Health, and recently published on medRxiv, they found that SARS-CoV-2 is stable in saliva for prolonged periods at warm temperatures, and that preservatives or specialized tubes are not necessary for collection of saliva.

Of course this part warmed my heart (doubly):

The related research was funded by the NBA, National Basketball Players Association, and a Fast Grant from the Emergent Ventures at the Mercatus Center, George Mason University.

The NBA had the wisdom to use its unique “bubble” to run multiple tests on players at once, to see how reliable the less-known tests would be. This WSJ article — “Experts say it could be key to increasing the nation’s testing capacity” — has the entire NBA back story. At an estimated $10 a pop, this could especially be a game-changer for poorer nations. Furthermore, it has the potential to make pooled testing much easier as well.

Here is an excerpt from the research pre-print:

The critical component of our approach is to use saliva instead of respiratory swabs, which enables non-invasive frequent sampling and reduces the need for trained healthcare professionals during collection. Furthermore, we simplified our diagnostic test by (1) not requiring nucleic acid preservatives at sample collection, (2) replacing nucleic acid extraction with a simple proteinase K and heat treatment step, and (3) testing specimens with a dualplex quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) assay. We validated SalivaDirect with reagents and instruments from multiple vendors to minimize the risk for supply chain issues. Regardless of our tested combination of reagents and instruments from different vendors, we found that SalivaDirect is highly sensitive with a limit of detection of 6-12 SARS-CoV-2 copies/μL.

No need to worry and fuss about RNA extraction now. Here is the best simple explanation of the whole thing.

The researchers are not seeking to commercialize their advance, rather they are making it available for the general benefit of mankind. Here is Nathan Grubaugh on Twitter. Here is Anne Wyllie, also a Kiwi and a Kevin Garnett fan. A further implication of course is that the NBA bubble is not “just sports,” but also has boosted innovation by enabling data collection.

All good news of course, and Fast at that. And this:

“This could be one the first major game changers in fighting the pandemic,” tweeted Andy Slavitt, a former acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the Obama administration, who expects testing capacity to be expanded significantly. “Rarely am I this enthusiastic… They are turning testing from a bespoke suit to a low-cost commodity.”

And here is coverage from Zach Lowe. I am very pleased with the course of Fast Grants more generally, and you will be hearing more about it in the future.

Using Social Media to Bring Down the Power Grid

Social media are a coordination device and coordinated behavior has many advantages. Social media was used to motivate, organize and coordinate movements like the Arab Spring and Black Lives Matter. Of course, coordination can also lead to conspiracy theories like QAnon, twitter mobs that police political correctness and riots that lead to death and destruction. For better or worse, coordinated behavior is likely to increase, creating more and more quickly moving mobs. The use and abuse of such mobs is only just beginning. One insidiously clever prospect is the use of seemingly benign coordination to bring down a power grid. What if everyone turns on their air conditioner and lights at the same time? In How weaponizing disinformation can bring down a city’s power grid, Raman et al. discuss how such a scenario could be generate by something seemingly as simple as sending fake coupons!

Social media has made it possible to manipulate the masses via disinformation and fake news at an unprecedented scale. This is particularly alarming from a security perspective, as humans have proven to be one of the weakest links when protecting critical infrastructure in general, and the power grid in particular. Here, we consider an attack in which an adversary attempts to manipulate the behavior of energy consumers by sending fake discount notifications encouraging them to shift their consumption into the peak-demand period. Using Greater London as a case study, we show that such disinformation can indeed lead to unwitting consumers synchronizing their energy-usage patterns, and result in blackouts on a city-scale if the grid is heavily loaded. We then conduct surveys to assess the propensity of people to follow-through on such notifications and forward them to their friends. This allows us to model how the disinformation may propagate through social networks, potentially amplifying the attack impact. These findings demonstrate that in an era when disinformation can be weaponized, system vulnerabilities arise not only from the hardware and software of critical infrastructure, but also from the behavior of the consumers.

Hat tip: Kevin Lewis.

Addendum: California is once again issuing rolling blackouts. Welcome to the future.

My Conversation with Nicholas Bloom

Excellent and interesting throughout, here is the transcript, video, and audio. Here is part of the summary:

He joined Tyler for a conversation about which areas of science are making progress, the factors that have made research more expensive, why government should invest more in R&D, how lean management transformed manufacturing, how India’s congested legal system inhibits economic development, the effects of technology on Scottish football hooliganism, why firms thrive in China, how weak legal systems incentivize nepotism, why he’s not worried about the effects of remote work on American productivity (in the short-term), the drawbacks of elite graduate programs, how his first “academic love” shapes his work today, the benefits of working with co-authors, why he prefers periodicals and podcasts to reading books, and more.

Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: If I understand your estimates correctly, efficacy per researcher, as you measure it, is falling by about 5 percent a year [paper here]. That seems phenomenally high. What’s the mechanism that could account for such a rapid decline?

BLOOM: The big picture — just to make sure everyone’s on the same page — is, if you look in the US, productivity growth . . . In fact, I could go back a lot further. It’s interesting — you go much further, and you think of European and North American history. In the UK that has better data, there was very, very little productivity growth until the Industrial Revolution. Literally, from the time the Romans left in whatever, roughly 100 AD, until 1750, technological progress was very slow.

Sure, the British were more advanced at that point, but not dramatically. The estimates were like 0.1 percent a year, so very low. Then the Industrial Revolution starts, and it starts to speed up and speed up and speed up. And technological progress, in terms of productivity growth, peaks in the 1950s at something like 3 to 4 percent a year, and then it’s been falling ever since.

Then you ask that rate of fall — it’s 5 percent, roughly. It would have fallen if we held inputs constant. The one thing that’s been offsetting that fall in the rate of progress is we’ve put more and more resources into it. Again, if you think of the US, the number of research universities has exploded, the number of firms having research labs.

Thomas Edison, for example, was the first lab about 100 years ago, but post–World War II, most large American companies have been pushing huge amounts of cash into R&D. But despite all of that increase in inputs, actually, productivity growth has been slowing over the last 50 years. That’s the sense in which it’s harder and harder to find new ideas. We’re putting more inputs into labs, but actually productivity growth is falling.

COWEN: Let’s say paperwork for researchers is increasing, bureaucratization is increasing. How do we get that to be negative 5 percent a year as an effect? Is it that we’re throwing kryptonite at our top people? Your productivity is not declining 5 percent a year, or is it? COVID aside.

BLOOM: COVID aside. Yeah, it’s hard to tell your own productivity. Oddly enough, I always feel like, “Ah, you know, the stuff that I did before was better research ideas.” And then something comes along. I’d say personally, it’s very stochastic. I find it very hard to predict it. Increasingly, it comes from working with basically great, and often younger, coauthors.

Why is it happening at the aggregate level? I think there are three reasons going on. One is actually come back to Ben Jones, who had an important paper, which is called, I believe, “[Death of the] Renaissance Man.” This came out 15 years ago or something. The idea was, it takes longer and longer for us to train.

Just in economics — when I first started in economics, it was standard to do a four-year PhD. It’s now a six-year PhD, plus many of the PhD students have done a pre-doc, so they’ve done an extra two years. We’re taking three or four years longer just to get to the research frontier. There’s so much more knowledge before us, it just takes longer to train up. That’s one story.

A second story I’ve heard is, research is getting more complicated. I remember I sat down with a former CEO of SRI, Stanford Research Institute, which is a big research lab out here that’s done many things. For example, Siri came out of SRI. He said, “Increasingly it’s interdisciplinary teams now.”

It used to be you’d have one or two scientists could come up with great ideas. Now, you’re having to combine a couple. I can’t remember if he said for Siri, but he said there are three or four different research groups in SRI that were being pulled together to do that. That of course makes it more expensive. And when you think of biogenetics, combining biology and genetics, or bioengineering, there’s many more cross-field areas.

Then finally, as you say, I suspect regulation costs, various other factors are making it harder to undertake research. A lot of that’s probably good. I’d have to look at individual regulations. Health and safety, for example, is probably a good idea, but in the same way, that is almost certainly making it more expensive to run labs…

COWEN: What if I argued none of those are the central factors because, if those were true as the central factors, you would expect the wages of scientists, especially in the private sector, to be declining, say by 5 percent a year. But they’re not declining. They’re mostly going up.

Doesn’t the explanation have to be that scientific efforts used to be devoted to public goods much more, and now they’re being devoted to private goods? That’s the only explanation that’s consistent with rising wages for science but a declining social output from her research, her scientific productivity.

And this:

COWEN: What exactly is the value of management consultants? Because to many outsiders, it appears absurd that these not-so-well-trained young people come in. They tell companies what to do. Sometimes it’s even called fraudulent if they command high returns. How does this work? What’s the value added?

Definitely recommended

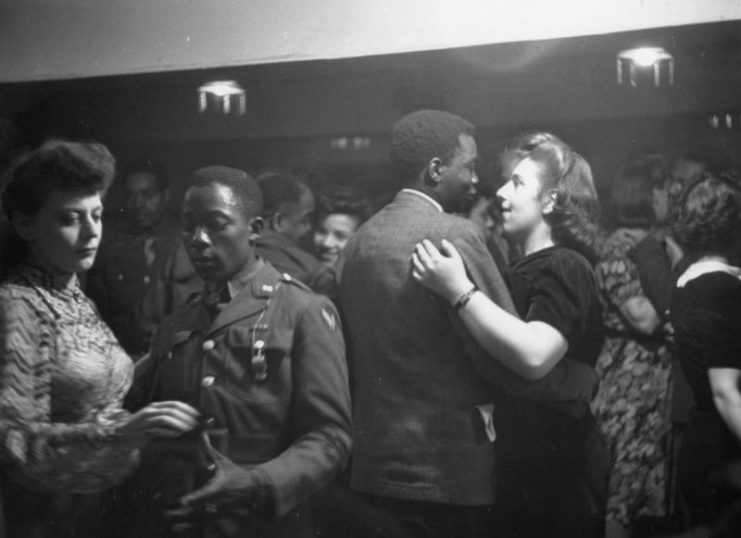

The Contemporary Impact of Black G.I.s in Europe in WWII

Abstract: Can attitudes towards minorities, an important cultural trait, be changed? We show that the presence of African American soldiers in the U.K. during World War II reduced anti-minority prejudice, a result of the positive interactions which took place between soldiers and the local population. The change has been persistent: in locations in which more African American soldiers were posted there are fewer members of and voters for the U.K.’s leading far-right party, less implicit bias against blacks and fewer individuals professing racial prejudice, all measured around 2010. Our results point towards intergenerational transmission from parents to children as the most likely explanation.

from a new paper by David Schindler and Mark Westcott in ReStud. Black GI’s also experienced a society with much less segregation than in the United States.

Mixed race couples dancing in a London club, 1943. Original Publication: Picture Post – 1486 – Inside London’s Coloured Clubs – pub. 1943 (Photo by Felix Man/Picture Post/Getty Images)

From this review.

You don’t have to think these are the major cybersecurity threats to USG to find this situation intolerable. There are also reports of Molotov cocktails and pipe bombs in or near Congress. You simply have to secure the physical building if you are to have credible security at all. I am very familiar with these entrances, and even an outnumbered force has the ability to keep out intruders, if it has the will to do so. In contrast, the Secret Service has a long history of agents using their bodies to block or shield presidents from threats of violence. Does Congress as a whole (which is harder to replace than a single president) deserve any less?