Results for “unemployment” 675 found

Was the New Deal Racist?

In recent decades, “racial disparity” has become the central framework for discussing inequities affecting African Americans in the United States. In this usage, disparity refers to the disproportionate statistical representation of some categorically defined populations on average in the distribution of undesirable things—unemployment, low wages, infant mortality, poor education, incarceration, etc. And by corollary logic, such social groupings are also found to be statistically underrepresented in desirable things—wealth, income, educational attainment, etc.

…Identifying disparate treatment or outcomes that correlate with racial difference can be a critical step in validating a complaint. However, the inclination to fixate on such disparities as the only objectionable form of inequality can create perverse political incentives. We devote a great deal of rhetorical and analytic energy to the project of determining just which groups, or population categories, suffer or have suffered the worst. Cynics have sometimes referred to this brand of what we might term political one-downsmanship as the “oppression Olympics”—a contest in which groups that have attained or are vying for legal protection effectively compete for the moral or cultural authority that comes with the designation of most victimized.

Even short of that cynical view, a central focus on group-level disparities can lead to mistaken diagnoses of the sources and character of the manifest inequalities it identifies.

Does Demand for New Currencies Increase in a Recession?

Every time there is a recession we hear more about barter and new currencies, especially so-called “local” currencies. An inceased interest in barter and new currencies suggests a theory of recessions, the lack of liquidity theory:

Bloomberg: “In times of crisis like the one we are jumping into, the main issue is lack of liquidity, even when there is work to be done, people to do it, and demand for it,” says Paolo Dini, an associate professorial research fellow at the London School of Economics and one of the world’s foremost experts on complementary currencies. “It’s often a cash flow problem. Therefore, any device or instrument that saves liquidity helps.”

I wrote about this several years ago but on closer inspection it’s not obvious that interest in barter or new currencies increases much in a recession or that these new currencies are helpful. Here’s my previous post (with a new graph) and no indent.

Nick Rowe explains that the essence of New Keynesian/Monetarist theories of recessions is the excess demand for money (Paul Krugman’s classic babysitting coop story has the same lesson). Here’s Rowe:

The unemployed hairdresser wants her nails done. The unemployed manicurist wants a massage. The unemployed masseuse wants a haircut. If a 3-way barter deal were easy to arrange, they would do it, and would not be unemployed. There is a mutually advantageous exchange that is not happening. Keynesian unemployment assumes a short-run equilibrium with haircuts, massages, and manicures lying on the sidewalk going to waste. Why don’t they pick them up? It’s not that the unemployed don’t know where to buy what they want to buy.

If barter were easy, this couldn’t happen. All three would agree to the mutually-improving 3-way barter deal. Even sticky prices couldn’t stop this happening. If all three women have set their prices 10% too high, their relative prices are still exactly right for the barter deal. Each sells her overpriced services in exchange for the other’s overpriced services….

The unemployed hairdresser is more than willing to give up her labour in exchange for a manicure, at the set prices, but is not willing to give up her money in exchange for a manicure. Same for the other two unemployed women. That’s why they are unemployed. They won’t spend their money.

Keynesian unemployment makes sense in a monetary exchange economy…it makes no sense whatsoever in a barter economy, or where money is inessential.

Rowe’s explanation put me in mind of a test. Barter is a solution to Keynesian unemployment but not to “RBC unemployment” which, since it is based on real factors, would also occur in a barter economy. So does barter increase during recessions?

There was a huge increase in barter and exchange associations during the Great Depression with hundreds of spontaneously formed groups across the country such as California’s Unemployed Exchange Association (U.X.A.). These barter groups covered perhaps as many as a million workers at their peak.

In addition, I include with barter the growth of alternative currencies or local currencies such as Ithaca Hours or LETS systems. The monetization of non-traditional assets can alleviate demand shocks which is one reason why it’s good to have flexibility in the definition of and free entry into the field of money (a theme taken up by Cowen and Kroszner in Explorations in New Monetary Economics and also in the free banking literature.)

During the Great Depression there was a marked increase in alternative currencies or scrip, now called depression scrip. In fact, Irving Fisher wrote a now forgotten book called Stamp Scrip. Consider this passage and note how similar it is to Nick’s explanation:

If proof were needed that overproduction is not the cause of the depression, barter is the proof – or some of the proof. It shows goods not over-produced but dead-locked for want of a circulating transfer-belt called “money.”

Many a dealer sits down in puzzled exasperation, as he sees about him a market wanting his goods, and well stocked with other goods which he wants and with able-bodied and willing workers, but without work and therefore without buying power. Says A, “I could use some of B’s goods; but I have no cash to pay for them until someone with cash walks in here!” Says B, “I could buy some of C’s goods, but I’ve no cash to do it with till someone with cash walks in here.” Says the job hunter, “I’d gladly take my wages in trade if I could work them out with A and B and C who among them sell the entire range of what my family must eat and wear and burn for fuel – but neither A nor B nor C has need of me – much less could the three of them divide me up.” Then D comes on the scene, and says, “I could use that man! – if he’d really take his pay in trade; but he says he can’t play a trombone and that’s all I’ve got for him.”

“Very well,” cries Chic or Marie, “A’s boy is looking for a trombone and that solves the whole problem, and solves it without the use of a dollar.

In the real life of the twentieth century, the handicaps to barter on a large scale are practically insurmountable….

Therefore Chic or somebody organizes an Exchange Association… in the real life of this depression, and culminating apparently in 1933, precisely what I have just described has been taking place.

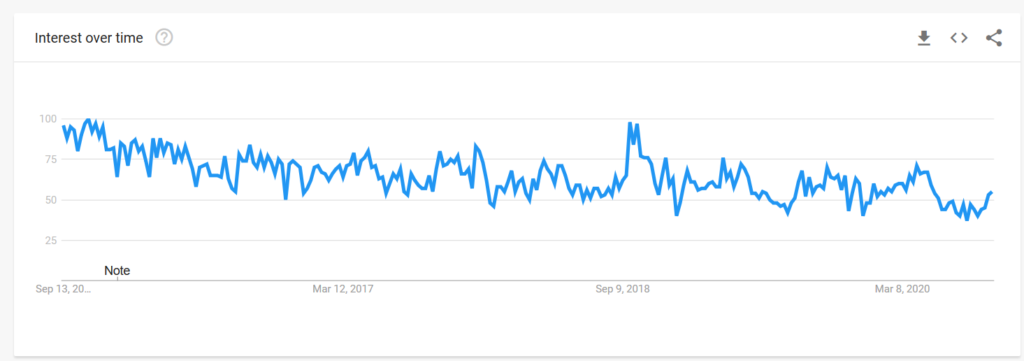

What about today (2011)? Unfortunately, the IRS doesn’t keep statistics on barter (although barterers are supposed to report the value of barter exchanges). Google Trends shows an increase in searches for barter in 2008-2009 but the increase is small. Some reports say that barter is up but these are isolated (see also the 2020 Bloomberg piece), I don’t see the systematic increase we saw during the Great Depression. I find this somewhat surprising as the internet and barter algorithms have made barter easier.

In terms of alternative currencies, the best data that I can find shows that the growth of alternative currencies in the United States is small, sporadic and not obviously increasing with the recession. (Alternative currencies are better known in Germany and Argentina perhaps because of the lingering influence of Heinrich Rittershausen and Silvio Gesell).

Below is a similar graph for 2017-2020. Again not much increase in recent times.

In sum, the increase in barter and scrip during the Great Depression is supportive of the excess demand for cash explanation of that recession, even if these movements didn’t grow large enough, fast enough to solve the Great Depression. Today there seems to be less interest in barter and alternative currencies than expected, or at least than I expected, given an AD shock and the size of this recession. I don’t draw strong conclusions from this but look forward to further research on unemployment, recessions and barter.

Fight the Virus! Please.

One of the most confounding aspects of the pandemic has been Congress’s unwillingness or inability to spend to fight the virus. As I said in the LA Times:

If an invader rained missiles down on cities across the United States killing thousands of people, we would fight back. Yet despite spending trillions on unemployment insurance and relief to deal with the economic consequences of COVID-19, we have spent comparatively little fighting the virus directly.

Economists Steven Berry and Zack Cooper have run the numbers:

By our calculations, less than 8 percent of the trillions in funding that Congress has allocated so far in response to the virus has been for solutions that would shorten or mitigate the virus itself: measures like increasing the supply of PPE, expanding testing, developing treatments, standing up contact tracing, or developing a vaccine. A case in point is the most recent House Covid-19 package. It calls for $3 trillion in spending; less than 3 percent of that total is allocated toward Covid testing. As Congress considers next steps, it’s imperative to shift priorities and direct more funding and effort toward actually ending the pandemic.

Berry and Copper point to the vaccine plan that I am working on as an example of smart spending:

…a group of prominent economists, including Nobel Laureate Michael Kremer, has proposed spending a $70 billion dollar vaccine effort. The proposed expenditure is both much larger than anything proposed by the White House or Congress and also quite cheap compared to the potential benefits.

…[Similarly] Nobel Laureate Paul Romer and the Rockefeller Foundation have each sketched out $100 billion plans to increase testing. We say: Let’s fund both, allocating half the funds directly to states, who can spend to activate the vast capacity of university labs, and also fund Romer’s plan to scale up $10 instant tests for true mass testing. We could create a $50 billion dollar challenge prize that rewards the first 10 firms that develop effective treatments for Covid-19 — $5 billion each. We could fund Scott Gottlieb and Andy Slavitt’s bipartisan $50 billion contact tracing proposal. We could allocate $100 billion to fund the libertarian leaning Mercatus Center’s proposal for advanced purchase contracts to procure massive quantities of PPE.

What makes this all the more confounding is that spending to defeat the virus will more than pay for itself! As I said in my piece in the Washington Post (with ):

Economists talk about “multipliers” — an injection of spending that causes even larger increases in gross domestic product. Spending on testing, tracing and paid isolation would produce an indisputable and massive multiplier effect.

Who gains by killing the economy and letting people die? Yes, it’s possible to spin some elaborate conspiracy about someone, somewhere benefiting. But in talking with people in Congress the message I hear is not that there’s a secret cabal with a special interest in economic collapse and dying constituents. In a way, the message is worse. Multiple people have told me that things move slowly, no one is stepping up to the plate, leadership is absent. “Who is John Galt?,” they sigh. Ok, they don’t literally say that, but that sigh of resignation is what it feels like in the United States today at the highest levels of government.

Claims about equities (and gamblers)

Mr. Young, 30, has only about $2,500 invested, making him a guppy among whales. But some Wall Street analysts see people who used to bet on sports as playing a big role in the market’s recent surge, which has largely erased its losses for the year.

“There’s zero doubt in my mind that it is a factor,” said Julian Emanuel, chief equity and derivatives strategist at the brokerage firm BTIG. “Zero doubt.”

Millions of small-time investors have opened trading accounts in recent months, a flood of new buyers unlike anything the market had seen in years, just as lockdown orders halted entire sectors of the economy and sent unemployment soaring.

It’s not clear how many of the new arrivals are sports bettors, but some are behaving like aggressive gamblers. There has been a jump in small bets in the stock options market, where wagers on the direction of share prices can produce thrilling scores and gut-wrenching losses. And transactions that make little economic sense, like buying up the nearly valueless shares of bankrupt companies, are off the charts.

File under “speculative,” here is the full NYT story.

Monday assorted links

1. The role of pollen: weird but interesting.

2. How has the coronavirus affected the reign of Xi?

3. “Advisors do not always want advisees to fully adopt their advice.”

4. “Recency negativity: Newer food crops are evaluated less favorably.“

5. A new study of which non-pharmaceutical interventions are most effective, argues that open schools can be a significant transmission mechanism.

6. Is large household size a critical problem?

7. Map of international travel restrictions related to Covid-19.

Operation Warp Speed Needs to Go to Warp 10

Operation Warp Speed is following the right plan by paying for vaccine capacity to be built even before clinical trials are completed. OWS, however, should be bigger and should have more diverse vaccine candidates. OWS has spent well under $5 billion. At current rates, the US economy is losing about $40 billion a week. Thus, if $20 billion could advance a vaccine by just one week that would be a good deal. As I said in the LA Times, “It might seem expensive to invest in capacity for a vaccine that is never approved, but it’s even more expensive to delay a vaccine that could end the pandemic.”

I am also concerned that OWS is narrowing down the list of candidates too early:

NYTimes: Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and the Oxford-AstraZeneca group have already received a total of $2.2 billion in federal funding to support their vaccine programs. Their selection as finalists, along with Merck and Pfizer, will give all five companies access to additional government money, help in running clinical trials and financial and logistical support for a manufacturing base that is being built even before it is clear which if any of the vaccines in development will work.

These are all good programs and one of them will probably be successful but we also want to support some long-shots because a small probability of a very big gain is still a big gain.

The five candidates also all use new technologies and are less diverse than I would prefer. There are a lot of different vaccine platforms, Live-Attenuated, Deactivated, Protein Subunit, Viral Vector, DNA and mRNA among others. The Accelerating Health Technologies team that I am a part of collected data on over 100 vaccine candidates and their characteristics. We then created a model to compute an optimal portfolio. We estimated that it’s necessary to have 15-20 candidates in the portfolio to get to a 80-90% chance of at least one success and that you want diverse candidates because the second candidate from the same platform probably fails if the first candidate from that platform fails. Moderna and Pfrizer are both mRNA vaccines–a platform that has never been used before–while AstraZeneca, Johnson and Johnson and Merck are using somewhat different viral vector platforms (Adenovirus for AstraZeneca and J & J and measles for Merck) which is also a relatively novel approach. I think it would be better if there were some tried and true platforms such as a Deactivated or Protein Subunit vaccine in the mix. As Larry Summers said, “if you will die of starvation if you don’t get a pizza in two hours, order 5 pizzas”. I would change that to order 10 pizzas and order from different companies!

One way to diversify the portfolio is to make deals with other countries to avoid the prisoner’s dilemma of vaccine portfolios. The prisoner’s dilemma is that each country has an incentive to invest in the vaccine most likely to succeed but if every country does this the world has put all its eggs in one basket. To avoid that, you need some global coordination. One country invests in Vaccine A, the other invests in Vaccine B and they agree to share capacity regardless of which vaccine works.

So my critique is that OWS is good policy but it would be even better if more vaccine candidates and more diverse vaccine candidates were part of the program. In contrast, the critiques being offered in Congress are ridiculous and dangerous.

Democrats in Congress are already seeking details about the contracts with the companies, many of which are still wrapped in secrecy. They are asking how much Americans will have to pay to be vaccinated and whether the firms, or American taxpayers, will retain the profits and intellectual property.

How much will Americans have to pay to be vaccinated??? A lot less than they are paying for not being vaccinated! The worry about profits is entirely backwards. The problem is that the profits of vaccine manufacturers are far too small to give them the correct social incentives not that the profits are too large. The stupidity of this is aggravating.

Skepticism about Trump administration policies is understandable but I am concerned that one of the best things the Trump administration is doing to combat the virus will be impeded and undermined by politics.

Fight the Virus!

I was asked by the LATimes to contribute to a panel on economic and pandemic policy. The other contributors are Joseph E. Stiglitz, Christina Romer, Alicia H. Munnell, Jason Furman, Anat R. Admati, James Doti, Simon Johnson, Ayse Imrohoroglu and Shanthi Nataraj. Here’s my contribution:

If an invader rained missiles down on cities across the United States killing thousands of people, we would fight back. Yet despite spending trillions on unemployment insurance and relief to deal with the economic consequences of COVID-19, we have spent comparatively little fighting the virus directly.

Testing capacity has slowly increased, but where is the national program to create a dozen labs each running 200,000 tests a day? It’s technologically feasible but months into the crisis, we have only just begun to spend serious money on testing.

We haven’t even fixed billing procedures so we can use the testing capacity that already exists. That’s right, labs that could be running tests are idle because of billing procedures. And while some parts of our government are slow, the Food and Drug Administration seems intent on reducing America’s ability to fight the virus by demanding business-as-usual paperwork.

Operation Warp Speed is one of the few bright spots. Potential vaccines often fail and so firms will typically not build manufacturing capacity, let alone produce doses until after a vaccine has been approved. But if we follow the usual procedure, getting shots in arms could be delayed by months or even years.

Under Operation Warp Speed, the government is paying for capacity to be built now so that the instant one of 14 vaccine candidates is proven safe and effective, production will be ready to go. That’s exactly what Nobel-prize winning economist Michael Kremer, Susan Athey, Chris Snyder and I have recommended. It might seem expensive to invest in capacity for a vaccine that is never approved, but it’s even more expensive to delay a vaccine that could end the pandemic.

Relief payments can go on forever, but money spent on testing and vaccines has the potential to more than pay for itself. It’s time to fight back.

Alex Tabarrok is a professor of economics at George Mason University and a member of the Accelerating Health Technologies With Incentive Design team.

My point about not fighting the virus directly was illustrated by many of the other panelists. Joseph Stiglitz, Christina Romer, Alicia Munnell, Jason Furman, James Doti, and Shanthi Nataraj say nothing or next to nothing about viruses. Only Anat Admati, Simon Johnson, Ayse Imrohoroglu get it.

Admati supports a Paul Romer-style testing program:

Until effective vaccines and therapies are available, which may be many months away, our best approach is to invest heavily in increasing the capacity for testing many more people and isolating those infected.

Simon Johnson argues, in addition, for antibody tests (not the usual PCR tests):

Policymakers should go all-in on ramping up antibody testing, to determine who has been exposed to COVID-19. Such tests are not yet accurate enough to determine precise immunity levels, but the work of Michael Mina, an immunologist and epidemiologist at Harvard, and others demonstrates that using such tests in the right way generates not just information about what has happened but, because of what can be inferred about underlying disease dynamics, also the information we need to understand where the disease will likely next impact various local communities.

Imrohoroglu advocates for targeted lockdown:

In addition to CDC recommendations about social distancing and public health strategies for all, I believe that as we reopen, we should keep a targeted lockdown policy in place for at-risk groups.

*The Deficit Myth* and Modern Monetary Theory

That is the new book by Stephanie Kelton and the subtitle is Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. Here are a few observations:

1. Much of it is quite unobjectionable and well-known, dating back to the Bullionist debates or earlier yet. Yet regularly it flies off the handle and makes unsupported macroeconomic assertions.

2. Like many of the Austrians, Kelton likes to insist on special terms, such as the government spending “coming first.” You don’t have to say this is wrong, just keep your eye on the ball and don’t let it distract you.

3. “MMT has emphasized that rising interest income can serve as a potential form of fiscal stimulus.” You don’t have to believe in a naive form of Say’s Law, but discussions of demand should start with the notion of production. Then…never reason from an interest rate change! Overall, I sense Kelton has one core model of the macroeconomy, with a whole host of variables held fixed (“well…higher interest rates means printing up more money to pay for them and thus greater stimulus…”), and then applies that model to a whole series of quite general problems and questions.

4. She thinks “demand” simply puts resources to work, and in this sense the book is a nice reductio ad absurdum of the economics one increasingly sees from mainstream writers on Twitter. p.s.: The economy doesn’t have a “speed limit.” And it shouldn’t be modeled using analogies with buckets.

5. We are told that the U.S. “…can’t lose control of its interest rate”, but real and nominal interest rates are not distinguished with care in these discussions. The Fed’s ability to control real rates is fairly limited, though not zero, and those are empirical truths never countered or even confronted in this book.

6. The absence of a nominal budget constraint is confused repeatedly with the absence of a real budget constraint. That is one of the major errors in this book.

7. It still would be very useful if the MMT people would take a mainstream macro model and spell out which assumptions they wish to make different, and then solve for the properties of the new model. There is a reason why they won’t do that.

8. I don’t care what the author says or how canonical she is as a source, a federal jobs guarantee is not part of MMT.

9. Just because the economy is not at absolute full unemployment, it does not mean that free resources are on the table for the taking. Again, in this regard Kelton is a useful reductio on a lot of “Twitter macro.”

10. I am plenty well read in the “money cranks” of earlier times, including Soddy, Foster, Catchings, Kitson, Proudhon, Tucker, and many more. They got a lot of things right, but they also failed to produce coherent macro theories. I would strongly recommend that Kelton undertake a close study of their failings.

11. For all the criticisms of the quantity theory, I would like to know how the MMT people explain the Fed coming pretty close to its inflation rate target for many years in a row, under highly varying conditions, fiscal conditions too.

12. The real grain of truth here is that if monetary policy is otherwise too deflationary, monetizing parts or all of the budget deficit is not only possible, it is desirable. Absolutely, but don’t then let somebody talk loops around you.

You can order the book here.

Stansbury and Summers on the declining bargaining power of labor

In one of the best papers of the year, Anna Stansbury and Larry Summers present what is to me the best non-“Great Stagnation” story of what has gone wrong, and I have read many such accounts. Here is their abstract:

Rising profitability and market valuations of US businesses, sluggish wage growth and a declining labor share of income, and reduced unemployment and inflation, have defined the macroeconomic environment of the last generation. This paper offers a unified explanation for these phenomena based on reduced worker power. Using individual, industry, and state-level data, we demonstrate that measures of reduced worker power are associated with lower wage levels, higher profit shares, and reductions in measures of the NAIRU. We argue that the declining worker power hypothesis is more compelling as an explanation for observed changes than increases in firms’ market power, both because it can simultaneously explain a falling labor share and a reduced NAIRU, and because it is more directly supported by the data.

There is a good deal of critical thinking about how different macroeconomic trends fit together, and a willingness to consider disconfirming evidence, so I do recommend you read through this one.

I have five main worries about the argument:

1. Rather than labor losing bargaining power, I think of the key development as “management measuring the marginal product of labor more precisely.” Admittedly that does lower the bargaining power of the majority of workers, given the 20/80 rule, or whatever you think the proper proportions are (Stansbury and Summers themselves presumably are underpaid, but in general wage dispersion has been going up in high-skilled sectors).

A minority of highly productive workers have much more bargaining power than they did before, which doesn’t quite fit the “lower bargaining power per se” hypothesis. And under my interpretation, easier unionization may not be much of a solution, since the problem here is the actual reality of who produces what. Consistent with my view, labor’s share is not really down if you consider the super-talented labor/owners/capitalists who start their own companies. That is a return to labor as well.

2. It is a noted advantage of the Stansbury and Summers approach that is explains the now-lower natural rate of unemployment. The puzzle, I think, is to explain both lower NAIRU and the slower labor market matching observed over the post-2009 labor market recovery. Their hypothesis seems to predict a higher degree of worker desperation, and thus quicker matches, than what we actually observed.

If you think, as I do, that employers are now better aware of the diversity of worker quality, and that only ex post do they learn that quality, employers will be more careful upfront, which probably does slow down matching speeds, thus fitting the data better.

3. If you play down market power, and postulate a fall in the share of labor, you might expect investment to be robust, but measured investment clocks in as mediocre. The authors discuss this point at length on pp.45-46 and offer multiple rebuttals, but I suppose I still think the first-order effect here ought to be stronger than what we (seem to) observe.

4. If corporate profits are so high, how is this consistent with the persistently low demand postulated by Summers’s “secular stagnation” hypothesis? The paper does consider this question very directly on p.56, but I genuinely (just as a matter of grammar) do not understand the answer the authors are suggesting. Here goes:

A fair question about the labor rents hypothesis regards what it says about the secular stagnation hypothesis that one of us has put forward (Summers 2013). We believe that the shift towards more corporate income,that occurs as labor rents decline,operates to raise saving and reduce demand. The impact on investment of reduced labor power seems to us ambiguous, with lower labor costs on the one hand encouraging expanded output and on the other encouraging more labor-intensive production, as discussed in Section V.So,decreases in labor power may operate to promote the reductions in demand and rising gap between private saving and investment that are defining features of secular stagnation.

I suppose I had thought of low rates of profit as a (though not the?) defining feature of secular stagnation, but again I may not have understood this passage correctly.

5. Matt Rognlie found that the decline in labor’s share went to housing and land ownership, not capital.

In any case, here is a whole paper full of economics, go and enjoy it.

Saturday assorted links

2. How is cocaine trafficking doing?

3. Edenville dam failure caught on video.

4. Ten arguments against immunity passports. I mean…those are the arguments you should make. But there is no conception that you have to “solve for the equilibrium” if there are no formal immunity passports, and compare the two situations in terms of cost, unfairness, and the like. In that sense the authors cannot conceive that there needs to be a comparison at all.

6. Do proponents of moral outrage wish to “sneak up on women”? That would explain a lot.

7. The import of super-spreaders in Israel.

8. American Interest interview with Larry Summers. “LHS: There’s a lot of empirical evidence since Keynes wrote, and for every non-employed middle-aged man who’s learning to play the harp or to appreciate the Impressionists, there are a hundred who are drinking beer, playing video games, and watching 10 hours of TV a day.” It’s a good thing that has nothing to do with subsequent delayed re-employment (also known as “unemployment”), isn’t it?

The economy that is New Brunswick (that’s Canada, not New Jersey)

Middle and high school students to process lobster after temporary foreign worker ban

With lobster processing set to begin Sunday, desperate New Brunswick seafood plants are turning to high school and even middle school students to fill the gap left by temporary foreign workers.

The decision by the Higgs government to block foreign workers amid the coronavirus pandemic has left processors in the province saying they have only about half the workforce they need, while counterparts in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island are ready to go “full tilt.”

“[The province] pulled the rug from under our feet,” said Russel Jacob, owner of Westmorland Fisheries in Cap Pele…

Middle school students must have permission from their parents and will make about $13 an hour.

High school students will be paid about $15 an hour.

Jacob expects they will not perform nearly as well as the experienced foreign workers.

Here is the full story, via Eric Hendry.

My initial point of course was one about the value of immigrants. But might it also be said that a significant chunk of the rising unemployment in New Brunswick is voluntary? Admittedly not everyone is sufficiently able-bodied to perform the work, but if junior high school students can do it…that means that many of the unemployed adults are simply unwilling to take these jobs? Is one allowed to say that these days? It doesn’t have to mean the government should do nothing about the broader economic crisis.

Is the coronavirus making UBI look better?

My last Bloomberg column was co-authored with Garry Kasparov, here is one excerpt:

Another positive sign for UBI is that most Americans seem keen to return to their workplaces. One fear has been that UBI would lead to a couch-potato culture, with people choosing to stay at home even when they’re finally able to leave. But blue-collar service workers are continuing to brave the front lines even when faced with reasonably high risks of infection. They are not trying to get fired so they can collect unemployment. White-collar workers, meanwhile, are feeling restless and unproductive. Working from home may become more common, but most people seem eager to get back to the office — especially if the alternative is a combination workplace/schoolhouse.

And:

…the crisis is serving up a very different and inferior bargain than the one many original UBI supporters advocated. Institutionalizing emergency measures designed to respond to Covid-19 would be irresponsible. It would entrench UBI without the prerequisite productivity boom from artificial intelligence and automation. (For some time it appeared the opposite might happen — namely, an AI boom but no UBI.)

I can report that Garry was a real pleasure to work and co-author with. Here is my earlier Conversation with him.

Monday assorted links

1. Photos from Belarus, interesting in their own right but all the more so now.

2. More comments on the models.

3. The lockdown culture that is Ontario: “19-year-old charged after Mercedes clocked doing 308 km/h.”

4. Two million chickens to be killed because there aren’t enough workers to kill them.

5. Covid-19 has largely spared the baseball world (model this).

6. An argument that all will be well soon enough. Not my view, but happy to pass along this perspective from Lars Christensen.

The Risk of Immunity Passes

I argued earlier that if we have Immunity Passes they Must Be Combined With Variolation because “the demand to go back to work may be so strong that some people will want to become deliberately infected. If not done carefully, however, these people will be a threat to others, especially in their asymptomatic phase.” Thus, if we have immunity passes we must also have controlled infection.

In a new paper, Daniel Hemel and Anup Malani run the numbers and verify the intuition:

…Our topline result is that strategic self-infection would be privately rational for younger adults under a wide range of plausible parameters. This result raises two significant concerns. First, in the process of infecting themselves, younger adults may expose others—including older and/or immunocompromised individuals—to SARS-CoV-2, generating significant negative externalities. Second, even if younger adults can self-infect without exposing others to risk, large numbers of self-infections over a short timeframe after introduction of the immunity passport regime may impose significant congestion externalities on health care infrastructure. We then evaluate several interventions that could mitigate moral hazard under an immunity passport regime, including the extension of unemployment benefits, staggered implementation of passports, and controlled exposure of individuals who seek to self-infect. Our results underscore the importance of careful planning around moral hazard as part of any widescale immunity passport regime.

Labor market restructuring and its possible permanence

We find 3 new hires for every 10 layoffs caused by the shock and estimate that 42 percent of recent layoffs will result in permanent job loss.

That is from a new paper by Jose Maria Barrero, Nick Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, top experts on this and related topics. As for policy:

Unemployment benefit levels that exceed worker earnings, policies that subsidize employee retention, occupational licensing restrictions, and regulatory barriers to business formation will impede reallocation responses to the COVID-19 shock.